Supplemental Materials for the PREVENTS Roadmap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Yellow Powered by the Nationwide Sprint 4G LTE Network Table of Contents

How to Build a Successful Business with Flash Yellow powered by the Nationwide Sprint 4G LTE Network Table of Contents This playbook contains everything you need build a successful business with Flash Wireless! 1. Understand your customer’s needs. GO TO PAGE 3 2. Recommend Flash Yellow in strong service areas. GO TO PAGE 4 a. Strong service map GO TO PAGE 5 3. Help your customer decide on a service plan GO TO PAGE 6 4. Ensure your customer is on the right device GO TO PAGE 8 a. If they are buying a new device GO TO PAGE 9 b. If they are bringing their own device GO TO PAGE 15 5. Device Appendix – Is your customer’s device compatible? GO TO PAGE 28 2 Step 1. Understand your customer’s needs • Mostly voice and text - Flash Yellow network would be a good fit in most metropolitan areas. For suburban / rural areas, check to see if they live in a strong Flash Yellow service area. • Average to heavy data user - Check to see if they live in a strong Flash Yellow service area. See page 5. If not, guide them to Flash Green or Flash Purple network to ensure they get the best customer experience. Remember, a good customer experience is the key to keeping a long-term customer! 3 Step 2. Recommend Flash Yellow in strong areas • Review Flash Yellow’s strong service areas. Focus your Flash Yellow customer acquisition efforts on these areas to ensure high customer satisfaction and retention. See page 5. o This is a top 24 list, the network is strong in other areas too. -

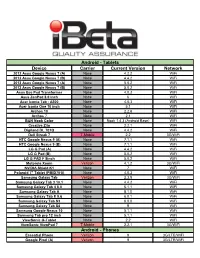

Ibeta-Device-Invento

Android - Tablets Device Carrier Current Version Network 2012 Asus Google Nexus 7 (A) None 4.2.2 WiFi 2012 Asus Google Nexus 7 (B) None 4.4.2 WiFi 2013 Asus Google Nexus 7 (A) None 5.0.2 WiFi 2013 Asus Google Nexus 7 (B) None 5.0.2 WiFi Asus Eee Pad Transformer None 4.0.3 WiFi Asus ZenPad 8.0 inch None 6 WiFi Acer Iconia Tab - A500 None 4.0.3 WiFi Acer Iconia One 10 inch None 5.1 WiFi Archos 10 None 2.2.6 WiFi Archos 7 None 2.1 WiFi B&N Nook Color None Nook 1.4.3 (Android Base) WiFi Creative Ziio None 2.2.1 WiFi Digiland DL 701Q None 4.4.2 WiFi Dell Streak 7 T-Mobile 2.2 3G/WiFi HTC Google Nexus 9 (A) None 7.1.1 WiFi HTC Google Nexus 9 (B) None 7.1.1 WiFi LG G Pad (A) None 4.4.2 WiFi LG G Pad (B) None 5.0.2 WiFi LG G PAD F 8inch None 5.0.2 WiFi Motorola Xoom Verizon 4.1.2 3G/WiFi NVIDIA Shield K1 None 7 WiFi Polaroid 7" Tablet (PMID701i) None 4.0.3 WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab Verizon 2.3.5 3G/WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab 3 10.1 None 4.4.2 WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab 4 8.0 None 5.1.1 WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab A None 8.1.0 WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab E 9.6 None 6.0.1 WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab S3 None 8.0.0 WiFi Samsung Galaxy Tab S4 None 9 WiFi Samsung Google Nexus 10 None 5.1.1 WiFi Samsung Tab pro 12 inch None 5.1.1 WiFi ViewSonic G-Tablet None 2.2 WiFi ViewSonic ViewPad 7 T-Mobile 2.2.1 3G/WiFi Android - Phones Essential Phone Verizon 9 3G/LTE/WiFi Google Pixel (A) Verizon 9 3G/LTE/WiFi Android - Phones (continued) Google Pixel (B) Verizon 8.1 3G/LTE/WiFi Google Pixel (C) Factory Unlocked 9 3G/LTE/WiFi Google Pixel 2 Verizon 8.1 3G/LTE/WiFi Google Pixel -

Sprint Complete

Sprint Complete Equipment Replacement Insurance Program (ERP) Equipment Service and Repair Service Contract Program (ESRP) Effective July 2021 This device schedule is updated regularly to include new models. Check this document any time your equipment changes and before visiting an authorized repair center for service. If you are not certain of the model of your phone, refer to your original receipt or it may be printed on the white label located under the battery of your device. Repair eligibility is subject to change. Models Eligible for $29 Cracked Screen Repair* Apple Samsung HTC LG • iPhone 5 • iPhone X • GS5 • Note 8 • One M8 • G Flex • G3 Vigor • iPhone 5C • iPhone XS • GS6 • Note 9 • One E8 • G Flex II • G4 • iPhone 5S • iPhone XS Max • GS6 Edge • Note 20 5G • One M9 • G Stylo • G5 • iPhone 6 • iPhone XR • GS6 Edge+ • Note 20 Ultra 5G • One M10 • Stylo 2 • G6 • iPhone 6 Plus • iPhone 11 • GS7 • GS10 • Bolt • Stylo 3 • V20 • iPhone 6S • iPhone 11 Pro • GS7 Edge • GS10e • HTC U11 • Stylo 6 • X power • iPhone 6S Plus • iPhone 11 Pro • GS8 • GS10+ • G7 ThinQ • V40 ThinQ • iPhone SE Max • GS8+ • GS10 5G • G8 ThinQ • V50 ThinQ • iPhone SE2 • iPhone 12 • GS9 • Note 10 • G8X ThinQ • V60 ThinQ 5G • iPhone 7 • iPhone 12 Pro • GS9+ • Note 10+ • V60 ThinQ 5G • iPhone 7 Plus • iPhone 12 Pro • A50 • GS20 5G Dual Screen • iPhone 8 Max • A51 • GS20+ 5G • Velvet 5G • iPhone 8 Plus • iPhone 12 Mini • Note 4 • GS20 Ultra 5G • Note 5 • Galaxy S20 FE 5G • GS21 5G • GS21+ 5G • GS21 Ultra 5G Monthly Charge, Deductible/Service Fee, and Repair Schedule -

Essential Phone on Its Way to Early Adopters 24 August 2017, by Seung Lee, the Mercury News

Essential Phone on its way to early adopters 24 August 2017, by Seung Lee, The Mercury News this week in a press briefing in Essential's headquarters in Palo Alto. "People have neglected hardware for years, decades. The rest of the venture business is focused on software, on service." Essential wanted to make a timeless, high-powered phone, according to Rubin. Its bezel-less and logo- less design is reinforced by titanium parts, stronger than the industry standard aluminum parts, and a ceramic exterior. It has no buttons in its front display but has a fingerprint scanner on the back. The company is also making accessories, like an attachable 360-degree camera, and the Phone will work with products from its competition, such as the Apple Homekit. Essential, the new smartphone company founded by Android operating system creator Andy Rubin, "How do you build technology that consumers are is planning to ship its first pre-ordered flagship willing to invest in?" asked Rubin. "Inter-operability smartphones soon. The general launch date for is really, really important. We acknowledge that, the Essential Phone remains unknown, despite and we inter-operate with companies even if they months of publicity and continued intrigue among are our competitors." Silicon Valley's gadget-loving circles. Recently, Essential's exclusive carrier Sprint announced it While the 5.7-inch phone feels denser than its will open Phone pre-orders on its own website and Apple and Samsung counterparts, it is bereft of stores. Essential opened up pre-orders on its bloatware - rarely used default apps that are website in May when the product was first common in new smartphones. -

Weekly Wireless Report August 18, 2017

Week Ending: Weekly Wireless Report August 18, 2017 This Week’s Stories Apple Is On The Hunt For Original TV Shows Inside This Issue: August 16, 2017 This Week’s Stories Apple is finally getting serious about original TV programming. Apple Is On The Hunt For Original TV Shows Two Apple executives have been meeting with Hollywood agents and producers to hear pitches about possible shows for Apple to buy, according to two producers who have met with them. Facebook Is Building A New $750 Million Data Center In Ohio The execs, Jamie Erlicht and Zack Van Amburg, were hired from Sony Pictures Television in June to oversee Apple's video programming. Products & Services New Apple, Samsung These pitch meetings have placed Apple in direct competition with Netflix, HBO and other Smartphone Challenger Is Finally distributors. Available For Pre-Order Some producers are eager to work with Apple, sensing a first-mover advantage. Others have a lot of YouTube TV Now Available To questions about how Apple will distribute its shows. When "House of Cards" debuted on Netflix, 50% Of U.S. Households marking the streaming service's entrance into original programming, the service already had a large catalog of licensed programming. Apple, Aetna Hold Secret Meetings To Bring Apple Watch To Millions Of Aetna Customers Apple doesn't have that -- but it does have iPhones in hundreds of millions of hands. Emerging Technology The meetings were first reported by The Wall Street Journal on Wednesday. Apple is said to be AI Is Taking Over The Cloud budgeting about $1 billion to acquire and produce original TV shows over the next year, according to the Journal. -

One Piece, Vol. 2: Buggy the Clown

[Read ebook] One Piece, Vol. 2: Buggy the Clown One Piece, Vol. 2: Buggy the Clown Eiichiro Oda DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub #163973 in Books VIZ Media, LLCModel: FBA-|284772 2003-10-22 2003-10-22Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 7.50 x .80 x 5.00l, .20 #File Name: 159116057X200 pagesViz Media | File size: 77.Mb Eiichiro Oda : One Piece, Vol. 2: Buggy the Clown before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised One Piece, Vol. 2: Buggy the Clown: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Hooked!By J.N. Cahill and Tom BlalockI am happy to report that I had a much easier time reading this the way you're supposed to than I did last time.Plot:I really enjoyed this plot and remember liking it in the anime, too. It's been so long since I've seen the beginning of the anime that I don't remember how closely it follows the manga, but it seems to be close. I adore the side story of Chouchou the most but I also like the addition of Nami.Setting:The overall setting of One Piece, when piracy is in it's golden age, is always fun. Best part in this one is the Pet Food Store that Chouchou guards.Characters:Luffy is just as funny as in the last one.Getting used to calling Zorro "Zolo" but I loved his attitude in this one. "Oh, I have a bad wound, I'll just sleep and it will be better soon. -

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Karya Sastra Merupakan

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Karya sastra merupakan hasil kreativitas pengarang yang menggunakan manusia dan segala macam segi kehidupannya sebagai objek karyanya. Sastra merupakan suatu kegiatan kreatif, sebuah karya seni (Wellek dan Warren , 1989: 3). Sastra juga bidang kajian yang begitu banyak mengandung bidang pandang. Sastra bagi sebagian orang dinilai sebagai kreasi seni yang mangandung nilai luhur, nilai moral yang berguna untuk mendidik umat. Bagi setengah orang pula, sastra dinilai sebagai kreasi seni yang didorong oleh gejolak bathin yang bersifat individual (Semi, 2008: 2). Sastra adalah suatu bentuk hasil dan pekerjaan seni kreatif yang obyeknya adalah manusia dan kehidupannya dengan menggunakan bahasa sebagai mediumnya (Semi, 1993: 8). Salah satu bidang kajian sastra yaitu psikologi sastra. Endraswara (2011: 96) mengatakan bahwa Psikologi sastra adalah kajian sastra yang memandang karya sebagai aktivitas kejiwaan. Pengarang akan menggunakan cipta, rasa, dan karya dalam berkarya. Begitu pula pembaca, dalam menanggapi karya juga tak akan lepas dari kejiwaan masing-masing. Di dalam psikologi sastra, tentunya terdapat sebuah konflik. Konflik merupakan pertentangan, percekcokan. Sedangkan konflik batin merupakan hal yang disebabkan oleh adanya dua gagasan atau lebih atau keinginan yang saling bertentangan untuk menguasai diri sehingga mempengaruhi tingkah laku. Salah satu contoh karya sastra yaitu komik. Komik secara internasional merupakan karya sastra yang menggunakan gambar-gambar tidak bergerak yang 1 disusun sedemikian rupa sehingga menjadi jalinan cerita. Biasanya, komik dicetak di atas kertas dengan tambahan teks cerita. Namun di berbagai negara komik memiliki nama tersendiri. Contohnya di Jepang komik disebut Manga, di Cina disebut dengan Manhua, di Korea disebut dengan Manhwa dan di Indonesia disebut dengan cerita gambar. -

Darkreader: Bridging the Gap Between Perception and Reality Of

DarkReader: Bridging the Gap Between Perception and Reality of Power Consumption in Smartphones for Blind Users Jian Xu∗ Syed Masum Billah* Roy Shilkrot Stony Brook University Stony Brook University Stony Brook University Stony Brook, USA Stony Brook, USA Stony Brook, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Aruna Balasubramanian Stony Brook University Stony Brook, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper presents a user study with 10 blind participants to understand their perception of power consumption in smart- phones. We found that a widely used power saving mechanism for smartphones–pressing the power button to put the smart- phone to sleep–has a serious usability issue for blind screen reader users. Among other findings, our study also unearthed several usage patterns and misconceptions of blind users that contribute to excessive battery drainage. Informed by the first user study, this paper proposes DarkReader, a screen reader developed in Android that bridges users’ perception of power consumption to reality. DarkReader darkens the screen by truly turning it off, but allows users to interact with their smart- phones. A second user study with 10 blind participants shows that participants perceived no difference in completion times in performing routine tasks using DarkReader and default screen reader. Yet DarkReader saves 24% to 52% power depending Figure 1. A blind user is interacting with his smartphone using a (A) on tasks and screen brightness. standard screen reader (e.g., TalkBack in Android), and (B) DarkReader. Unlike TalkBack, DarkReader keeps the screen off to save power. Author Keywords Vision impairment, blind; screen readers, TalkBack, Android, iOS; low-power, battery, screen, brightness; privacy, curtain INTRODUCTION mode, shoulder-surfing. -

![Arxiv:1910.06663V1 [Cs.PF] 15 Oct 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5599/arxiv-1910-06663v1-cs-pf-15-oct-2019-1465599.webp)

Arxiv:1910.06663V1 [Cs.PF] 15 Oct 2019

AI Benchmark: All About Deep Learning on Smartphones in 2019 Andrey Ignatov Radu Timofte Andrei Kulik ETH Zurich ETH Zurich Google Research [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Seungsoo Yang Ke Wang Felix Baum Max Wu Samsung, Inc. Huawei, Inc. Qualcomm, Inc. MediaTek, Inc. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lirong Xu Luc Van Gool∗ Unisoc, Inc. ETH Zurich [email protected] [email protected] Abstract compact models as they were running at best on devices with a single-core 600 MHz Arm CPU and 8-128 MB of The performance of mobile AI accelerators has been evolv- RAM. The situation changed after 2010, when mobile de- ing rapidly in the past two years, nearly doubling with each vices started to get multi-core processors, as well as power- new generation of SoCs. The current 4th generation of mo- ful GPUs, DSPs and NPUs, well suitable for machine and bile NPUs is already approaching the results of CUDA- deep learning tasks. At the same time, there was a fast de- compatible Nvidia graphics cards presented not long ago, velopment of the deep learning field, with numerous novel which together with the increased capabilities of mobile approaches and models that were achieving a fundamentally deep learning frameworks makes it possible to run com- new level of performance for many practical tasks, such as plex and deep AI models on mobile devices. In this pa- image classification, photo and speech processing, neural per, we evaluate the performance and compare the results of language understanding, etc. -

Projectreport.Pdf (2.519Mb)

! Mobile App Monetization – Expectations and Attitudes Formed by Users in Response to Advertising and Pay To Download Monetization Models Master’s Program Missouri School of Journalism University of Missouri by Anthony Brown Dr. Margaret Duffy, Committee Chair Jim Spencer Dr. Kevin Wise August, 2013 ii Acknowledgments Thanks to Dr. Duffy and Dr. Wise for their guidance and leadership throughout this too-lengthy process. Your patience and flexibility is a golden virtue. Thanks also to Jim Spencer, whose final firm push is exactly what I needed to put my head down and carry this research across the finish line. iii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT ............................................................................................ v Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1 2. ACTIVITIES DESCRIPTION ....................................................... 3 3. EVALUATION ........................................................................... 14 4. PHYSICAL EVIDENCE ............................................................. 15 5. ANALYSIS ................................................................................ 16 APPENDIX 1. ONLINE SURVEY TEXT AND RESULTS ................................ 31 2. FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION GUIDE AND TRANSCRIPT ... 61 3. PROJECT PROPOSAL ........................................................... -

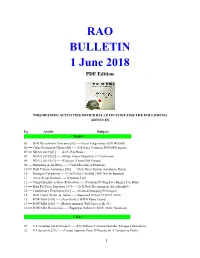

Bulletin 180601 (PDF Edition)

RAO BULLETIN 1 June 2018 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 05 == DoD Recruitment Concerns [01] ---- (Loan Forgiveness Bill HR.4508) 06 == China Territorial Claims [05] ---- (US Navy Conducts FONOPS Again) 07 == NDAA 2019 [01] ---- (2.6% Pay Raise) 07 == NDAA 2019 [02] ---- (White House Objects to 37 Provisions) 08 == NDAA 2019 [03] ---- (Progress | House Bill Passed) 08 == Munitions Availability ---- (Could Become A Problem) 10 == DoD Tuition Assistance [08] ---- (New Navy Tuition Assistance Rules) 10 == Pentagon Cellphones ---- (Use Policy Clarified | Will Not be Banned) 11 == Army Re-up Bonuses ---- (Updated List) 12 == Camp Humphreys Base Relocation ---- (Civilians PCSing Face Bigger Tax Bills) 13 == Burn Pit Toxic Exposure [49] ---- (Is It Now Becoming an Afterthought?) 14 == Commissary Employees [02] ---- (Granted Shopping Privileges) 14 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 MAY 2018) 15 == POW/MIA [101] ---- (Tom Kelly’s WWII Plane Found) 17 == POW/MIA [102] ---- (Robert Anspach Will Forever Be 33) 18 == POW/MIA Recoveries ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 MAY 2018 | Nineteen) . * VA * . 21 == VA Disabled Vet IG Project ---- ($12 Million ‘Colossal Mistake’ Enrages Lawmakers) 22 == VA Secretary [79] ---- (Trump Appoints Peter O’Rourke on A Temporary Basis) 1 23 == VA Medical Foster Home [02] ---- (Another Choice for Older Disabled Vets) 25 == VA Toxin Claims ---- (Children & Grandchildren | Thousands Missing) 26 == VA TeleStroke Program ---- -

Odyssey of the Cultural Narrative: Japan's Cultural Representation In

Global Media Journal-Indian Edition; Volume 13 Issue1; June 2021.ISSN:2249-5835 Odyssey of the cultural narrative: Japan’s cultural representation in Eiichiro Oda's One Piece Manish Prabhakar Singh Research Scholar, H.N.B. Garhwal University Uttarakhand Abstract One Piece is a Japanese Manga series drawn by Eiichiro Oda and published serially in Shueisha's Weekly Shonen Jump magazine since July 1997 and continuing with the same popularity. It portrays the adventures of Monkey D. Luffy, who dreams to become the Pirate King. He gained the properties of rubber after eating a Devil Fruit and is exploring the Grand Line along with his crewmates(The Straw Hat Pirates) in search of the eponymous legendary treasure 'One Piece' left by the former Pirate King Gol D. Roger. What makes this particular manga unique is Oda's representation of Japanese culture and tradition. He also uses some features similar to Ukiyo-e artworks, i.e., the woodblock art prints, which were targeted at the mass audience and also share thematic similarities. The influence of Ukiyo-e and Oda's love for Japanese art, along with its culture, folklore, and myths, is clearly seen in the ongoing Wano country arc. One Piece today has transcended the boundaries of manga, turning into a pop culture sensation in Japan. In the research paper, to apply the analytical and descriptive methods to the research, the original work, as well as the secondary sources available in the form of criticism, will be used. In my research, I will also try to apply the perspective of Cultural Studies.