Rojahn Et Al. 2021 Freshw Biol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lachlan Water Resource Plan

Lachlan Water Resource Plan Surface water resource description Published by the Department of Primary Industries, a Division of NSW Department of Industry, Skills and Regional Development. Lachlan Water Resource Plan: Surface water resource description First published April 2018 More information www.dpi.nsw.gov.au Acknowledgments This document was prepared by Dayle Green. It expands upon a previous description of the Lachlan Valley published by the NSW Office of Water in 2011 (Green, Burrell, Petrovic and Moss 2011, Water resources and management overview – Lachlan catchment ) Cover images: Lachlan River at Euabalong; Lake Cargelligo, Macquarie Perch, Carcoar Dam Photos courtesy Dayle Green and Department of Primary Industries. The maps in this report contain data sourced from: Murray-Darling Basin Authority © Commonwealth of Australia (Murray–Darling Basin Authority) 2012. (Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License) NSW DPI Water © Spatial Services - NSW Department of Finance, Services and Innovation [2016], Panorama Avenue, Bathurst 2795 http://spatialservices.finance.nsw.gov.au NSW Office of Environment and Heritage Atlas of NSW Wildlife data © State of New South Wales through Department of Environment and Heritage (2016) 59-61 Goulburn Street Sydney 2000 http://www.biotnet.nsw.gov.au NSW DPI Fisheries Fish Community Status and Threatened Species data © State of New South Wales through Department of Industry (2016) 161 Kite Street Orange 2800 http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/species-protection/threatened-species-distributions-in-nsw © State of New South Wales through the Department of Industry, Skills and Regional Development, 2018. You may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute the NSW Department of Primary Industries as the owner. -

Macquarie Perch Refuge Project – Final Report for Lachlan CMA Author: Luke Pearce, Fisheries Conservation Manager, NSW DPI, Albury

Published by NSW Trade & Investment, Department of Primary Industries First published May 2013 Title: Macquarie Perch Refuge Project – Final Report for Lachlan CMA Author: Luke Pearce, Fisheries Conservation Manager, NSW DPI, Albury. Print: ISBN 978 1 74256 500 2 Web: ISBN: 978 1 74256 501 9 Acknowledgements I thank the Lachlan Catchment Management Authority for providing the funding for the project. I would like to acknowledge the following staff, Fin Martin and Geoff Minchin for their input, assistance, advice and support on this project. The following staff in Fisheries NSW who worked on the project and made it possible; John Pursey, Dean Gilligan, Trevor Daly, Allan Lugg, Sarah Fairfull, Justin Stanger, Tim McGarry, Martin Asmus, Matthew McLellan, Lachie Jess and Antonia Creese. I thank the Recreational Fishing Trust for their ongoing support and funding for the Macquarie Perch captive breeding program; without it there would not be fish to stock into the refuge site. I would also like to acknowledge the Central Acclimatisation Society, in particular Karl Schaerf and Peter Byron for their ongoing support of the project and threatened native fish. TRIM reference: PUB13/61 Jobtrack 12067 © State of New South Wales through the Department of Trade and Investment, Regional Infrastructure and Services, 2013. You may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute the NSW Department of Primary Industries as the owner. Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing (May 2013). However, because of advances in knowledge, users are reminded of the need to ensure that information upon which they rely is up to date and to check currency of the information with the appropriate officer of the Department of Primary Industries or the user’s independent adviser. -

Erosion-Isostatic Rebound Models for Uplift: an Application to South-Eastern Australia

Geop/z.vs. J. R. astr. Soc. (1985) 82, 31-55 Erosion-isostatic rebound models for uplift: an application to south-eastern Australia Randell Stephenson* and Kurt Lambeck Research scilooiof Earth Sciences, Australian National Utliversit)’, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia Accepted 1984 Deccmber 17. Received 1984 September 10; in original form 1983 December 9 Summary. A mountain’s history includes two distinctive phases. one of active tectonism and construction followed by one of erosion and passive isostatic rebound. In the first phase uplift is driven by tectonic mechanisms while in the second phase base levels of the terrain are regionally uplifted. It is this latter phase that is modelled here. The starting model is a mountain range, initially in isostatic equilibrium, on a viscoelastic plate defined by the effective flexural rigidity D and relaxation time 7,. The rate of erosion at any time t is assumed to be proportional to the elevation at that time, with an erosional time constant 7,. For a given present-day topography the uplift, erosion, gravity, and stress can be computed through time as functions of D, 7,. 7,, and the time to at which the erosional-rebound mechanism became the dominant landscaping process. The model has been applied to the highlands of south-eastern Australia which we assume to be an erosional residue of the Palaeozoic Lachlan Fold Belt. Observations of rivers cutting through Cainozoic basalts and other geomorphological indicators of uplift can then be inter- preted in terms of the isostatic rebound and there is no need to invoke active tectonic uplift mechanisms. The model parameters that fit the observations are T,= 150-3-50Myr, DT~-2.5 x IOz4NmMyr and to- 180-200Myr. -

Appendix 1 - Fish Species Occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271

Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271 Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins Table 1 Fish species recorded in the Richmond River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 203) in the NSW Rivers Survey ("1996 Survey") and a previous study (Llewellyn 1983)("1983 Survey"). Site code Site name Stream Nearest town NCRL46 Casino Richmond River Casino NCRL50 Dunoon Rocky Creek Lismore NCRL48 Tintenbar Emigrant Creek Tintenbar NCUL60 Lismore Leycester Creek Lismore Species 1996 Survey* 1983 Survey Acanthopagrus australis 10 Ambassis agassizii 10 Ambassis nigripinnis 11 Anguilla australis 01 Anguilla reinhardtii 10 Arius graeffei 10 Arrhamphus sclerolepis 10 Carcharhinus leucas 10 Gambusia holbrooki 11 Gnathanodon speciosus 10 Gobiomorphus australis 11 Gobiomorphus coxii 01 Herklotsichthys castelnaui 10 Hypseleotris compressa 11 Hypseleotris galii 11 Hypseleotris spp 1 0 Liza argentea 10 Macquaria colonorum 10 Macquaria novemaculeata 10 Melanotaenia duboulayi 11 Mugil cephalus 11 Myxus petardi 11 Notesthes robusta 11 Philypnodon grandiceps 10 Philypnodon sp1 1 0 Platycephalus fuscus 10 Potamalosa richmondia 10 Pseudomugil signifer 11 Retropinna semoni 11 Tandanus tandanus 11 Total 28 14 *1 - Species recorded, 0 - Species not recorded (Details of fish records at individual sites and times are given in Harris et al. (1996). CRC For Freshwater Ecology RACAC NSW Fisheries 272 NSW Rivers Survey Table 2 Fish species recorded in the Clarence River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 204) in the NSW Rivers -

Gemstones and Geosciences in Space and Time Digital Maps to the “Chessboard Classification Scheme of Mineral Deposits”

Earth-Science Reviews 127 (2013) 262–299 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Gemstones and geosciences in space and time Digital maps to the “Chessboard classification scheme of mineral deposits” Harald G. Dill a,b,⁎,BertholdWeberc,1 a Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, P.O. Box 510163, D-30631 Hannover, Germany b Institute of Geosciences — Gem-Materials Research and Economic Geology, Johannes-Gutenberg-University, Becherweg 21, D-55099 Mainz, Germany c Bürgermeister-Knorr Str. 8, D-92637 Weiden i.d.OPf., Germany article info abstract Article history: The gemstones, covering the spectrum from jeweler's to showcase quality, have been presented in a tripartite Received 27 April 2012 subdivision, by country, geology and geomorphology realized in 99 digital maps with more than 2600 mineral- Accepted 16 July 2013 ized sites. The various maps were designed based on the “Chessboard classification scheme of mineral deposits” Available online 25 July 2013 proposed by Dill (2010a, 2010b) to reveal the interrelations between gemstone deposits and mineral deposits of other commodities and direct our thoughts to potential new target areas for exploration. A number of 33 categories Keywords: were used for these digital maps: chromium, nickel, titanium, iron, manganese, copper, tin–tungsten, beryllium, Gemstones fl Country lithium, zinc, calcium, boron, uorine, strontium, phosphorus, zirconium, silica, feldspar, feldspathoids, zeolite, Geology amphibole (tiger's eye), olivine, pyroxenoid, garnet, epidote, sillimanite–andalusite, corundum–spinel−diaspore, Geomorphology diamond, vermiculite–pagodite, prehnite, sepiolite, jet, and amber. Besides the political base map (gems Digital maps by country) the mineral deposit is drawn on a geological map, illustrating the main lithologies, stratigraphic Chessboard classification scheme units and tectonic structure to unravel the evolution of primary gemstone deposits in time and space. -

Find Your Local Brigade

Find your local brigade Find your district based on the map and list below. Each local brigade is then listed alphabetically according to district and relevant fire control centre. 10 33 34 29 7 27 12 31 30 44 20 4 18 24 35 8 15 19 25 13 5 3 45 21 6 2 14 9 32 23 1 22 43 41 39 16 42 36 38 26 17 40 37 28 11 NSW RFS Districts 1 Bland/Temora 13 Hawkesbury 24 Mid Coast 35 Orana 2 Blue Mountains 14 Hornsby 25 Mid Lachlan Valley 36 Riverina 3 Canobolas 15 Hunter Valley 26 Mid Murray 37 Riverina Highlands 4 Castlereagh 16 Illawarra 27 Mid North Coast 38 Shoalhaven 5 Central Coast 17 Lake George 28 Monaro 39 South West Slopes 6 Chifley Lithgow 18 Liverpool Range 29 Namoi Gwydir 40 Southern Border 7 Clarence Valley 19 Lower Hunter 30 New England 41 Southern Highlands 8 Cudgegong 20 Lower North Coast 31 North West 42 Southern Tablelands 9 Cumberland 21 Lower Western 32 Northern Beaches 43 Sutherland 10 Far North Coast 22 Macarthur 33 Northern Rivers 44 Tamworth 11 Far South Coast 23 MIA 34 Northern Tablelands 45 The Hills 12 Far West Find your local brigade 1 Find your local brigade 1 Bland/Temora Springdale Kings Plains – Blayney Tara – Bectric Lyndhurst – Blayney Bland FCC Thanowring Mandurama Alleena Millthorpe Back Creek – Bland 2 Blue Mountains Neville Barmedman Blue Mountains FCC Newbridge Bland Creek Bell Panuara – Burnt Yards Blow Clear – Wamboyne Blackheath / Mt Victoria Tallwood Calleen – Girral Blaxland Cabonne FCD Clear Ridge Blue Mtns Group Support Baldry Gubbata Bullaburra Bocobra Kikiora-Anona Faulconbridge Boomey Kildary Glenbrook -

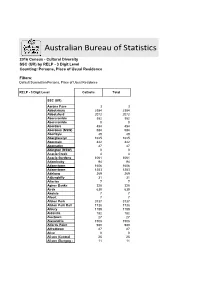

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census - Cultural Diversity SSC (UR) by RELP - 3 Digit Level Counting: Persons, Place of Usual Residence Filters: Default Summation Persons, Place of Usual Residence RELP - 3 Digit Level Catholic Total SSC (UR) Aarons Pass 3 3 Abbotsbury 2384 2384 Abbotsford 2072 2072 Abercrombie 382 382 Abercrombie 0 0 Aberdare 454 454 Aberdeen (NSW) 584 584 Aberfoyle 49 49 Aberglasslyn 1625 1625 Abermain 442 442 Abernethy 47 47 Abington (NSW) 0 0 Acacia Creek 4 4 Acacia Gardens 1061 1061 Adaminaby 94 94 Adamstown 1606 1606 Adamstown 1253 1253 Adelong 269 269 Adjungbilly 31 31 Afterlee 7 7 Agnes Banks 328 328 Airds 630 630 Akolele 7 7 Albert 7 7 Albion Park 3737 3737 Albion Park Rail 1738 1738 Albury 1189 1189 Aldavilla 182 182 Alectown 27 27 Alexandria 1508 1508 Alfords Point 990 990 Alfredtown 27 27 Alice 0 0 Alison (Central 25 25 Alison (Dungog - 11 11 Allambie Heights 1970 1970 Allandale (NSW) 20 20 Allawah 971 971 Alleena 3 3 Allgomera 20 20 Allworth 35 35 Allynbrook 5 5 Alma Park 5 5 Alpine 30 30 Alstonvale 116 116 Alstonville 1177 1177 Alumy Creek 24 24 Amaroo (NSW) 15 15 Ambarvale 2105 2105 Amosfield 7 7 Anabranch North 0 0 Anabranch South 7 7 Anambah 4 4 Ando 17 17 Anembo 18 18 Angledale 30 30 Angledool 20 20 Anglers Reach 17 17 Angourie 42 42 Anna Bay 789 789 Annandale (NSW) 1976 1976 Annangrove 541 541 Appin (NSW) 841 841 Apple Tree Flat 11 11 Appleby 16 16 Appletree Flat 0 0 Apsley (NSW) 14 14 Arable 0 0 Arakoon 87 87 Araluen (NSW) 38 38 Aratula (NSW) 0 0 Arcadia (NSW) 403 403 Arcadia Vale 271 271 Ardglen -

Visit Queanbeyan-Palerang Visitors Guide 2020

Queanbeyan vi it Palerang BRAIDWOOD, BUNGENDORE, QUEANBEYAN & SURROUNDS Acknowledgment of Country We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the Queanbeyan-Palerang area, the Ngunnawal and the Walbunja peoples. We pay our respect and celebrate their ongoing cultural traditions and contributions to our surrounding region. G What’s in ide WELCOME Take time to wander 6 GETTING HERE Map, travel times & distances 8 STEP OUTSIDE 42 LIVING HERITAGE 46 ON THE MENU 50 EXPLORE Start your journey here 54 MAKERS & CREATORS 56 EVENTS Save the date 58 EXPLORE FURTHER Tablelands region 60 SERVICES & INFORMATION Visitor Information Centres 64 Region map 66 OUR PLACES Braidwood & Villages 10 Bungendore & Surrounds 20 Queanbeyan District 26 Towns & Villages 36 IMAGES Front cover: Penance Grove Walk, Monga National Park. Opposite: Blacksmith Lane, Queanbeyan. 4 visitqueanbeyanpalerang.com.au Discover your visitqueanbeyanpalerang.com.au 5 Take time to The Kingswander Highway runs through the heart of Queanbeyan- Palerang and links Canberra to the sparkling waters of the South Coast of NSW. It is a region full of contrastC with a distinctive character of its own. From the future-focused city of Queanbeyan, to the historic township of Braidwood and the delightful country town of Bungendore, there’s something for everyone to explore and uncover. 6 #VisitQueanbeyanPalerang IMAGES Left to right: London Bridge, Googong; Suki & Hugh, Bungendore. TAKE TIME TO WANDER IN QUEANBEYAN-PALERANG; A STONE’S THROW FROM CANBERRA, BUT WITH A DISTINCTIVE CHARACTER OF ITS VERY OWN. Experience the essence of the region by meeting the makers behind Queanbeyan-Palerang’s unique products and produce. Chat to TOWNS & VILLAGES winemakers at local vineyards, join a truffle farmer on a hunt, get NOT TO BE MISSED hands on with a cooking class, then learn a few tricks of the trade Braidwood from local craftspeople and artists. -

Four Wheel Drive Adventures Across Australia

FOUR WHEEL DRIVE ADVENTURES ACROSS AUSTRALIA A resource containing interesting destinations, sights, activities, four wheel driving tracks and camping information in Australia. Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means now known or to be invented, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without written permission from the author or publisher, except for the brief inclusion of quotation in a review. Disclaimer Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information provided is on an “as is” basis. The author and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained in this book. ISBN 978 0 646 49401 2 Copyright © 2008 by Klara Slabenak Author: Slabenak, Klara. Title: Four wheel drive adventures across Australia / Klara Slabenak. Edition: 1st ed. ISBN: 9780646494012 (pbk.) Subjects: Motor vehicles--Australia--Recreational use Four-wheel drive vehicles--Australia Australia--Guidebooks Australia--Maps, Tourist. Dewey Number: 919.40463 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................1 PLANNING LEAVE..............................................................................................................................2 -

Private Native Forestry Field Guide for the River Red Gum Forests

Appendices Appendix A: Listing of major rivers that exist within the River Red Gum Forests Major rivers BARWON RIVER from the confluence of the Macintyre River and Weir River (Qld) near Mungindi and extending to its confluence with the Culgoa River BIRRIE RIVER BOKHARA RIVER CULGOA RIVER DUMARESQ RIVER from the confluence of the Dumaresq or Severn River (Qld) and Tenterfield Creek and extending to its confluence with Macintyre River MACINTYRE RIVER from its source near Glencoe to its confluence with the Weir River (Qld) near Mungindi DARLING RIVER from its confluence with the Culgoa River to its junction with the Murray River GWYDIR RIVER (GWYDIR RIVER, GOONAL BRANCH of GWYDIR RIVER [Part], BIG LEATHER WATERCOURSE [Part], BALLONE CREEK [Part], BUNDARRA or GWYDIR RIVER) NAMOI RIVER from its source to its junction with the Barwon River at Walgett BOGAN RIVER from its source to its junction with the Barwon River CASTLEREAGH RIVER from its source to its junction with the Macquarie River MACQUARIE OR WAMMERAWA RIVER from its source to its junction with the Barwon River LACHLAN RIVER from its source to its junction with the Murrumbidgee River MURRUMBIDGEE RIVER from its source to its junction with the Murray River MURRAY RIVER from its source to the South Australian border NARRAN RIVER PAROO RIVER WARREGO RIVER 92 Appendix B: Listing of prescribed streams & permanent watercourses that exist within the River Red Gum Forests DARLING RIVER from its confluence with the Culgoa River to its junction with the Murray River and the following tributaries -

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Macquarie Perch (Macquaria Australasica)

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Macquarie Perch (Macquaria australasica) March 2017 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 Draft National Recovery Plan for Macquarie Perch (Macquaria australasica) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This report should be attributed as ‘Draft National Recovery Plan for Macquarie Perch (Macquaria australasica), Commonwealth of Australia 2017’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. General Acknowledgements The Department of the Environment and Energy is grateful to the organisations and individuals who contributed to or provided information for the preparation of this draft recovery plan and were or are still involved in implementing conservation and management actions that benefit Macquarie perch. -

Abercrombie River National Park Fire Management Strategydownload

Abercrombie River National Park Fire Management Strategy NSW NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE SERVICE FIRE MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ABERCROMBIE RIVER NATIONAL PARK NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Blue Mountains Region June, 2005 Abercrombie River National Park Fire Management Strategy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2001 document was principally prepared by Conacher Travers Pty Ltd Bushfire and Ecological Consultants 70 Chivers Road, Somersby NSW, 2250. (ph) 02 4372 1244 (fax) 02 4372 1528 email [email protected] The following people and organisations made valuable contributions: Jules Bros NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Marca de Beer NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Arthur Henry NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Julie Pownall NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Saskia Hayes NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Aotea Christenson NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Eddie Gibbons Oberon Council Members Oberon Bushfire Management Committee Andrew Croft Forests NSW (Formerly State Forests) Debbie Mukhar Forests NSW (Formerly State Forests) Richard Bell NSW Rural Fire Service – Jerrong/Paling Yards Brigade/neighbour John Byrne Landholder Cover Photograph by: S. Douglas © National Parks and Wildlife Service This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. Published by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Blue Mountains Region, June, 2005. Contact : PO Box 552, Katoomba. NSW 2780 Erratum: Please note that this Strategy was first drafted in 2001. It has had a minor review to update it in 2004.