Alexander Merkushev at a Moscow Itself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Lenins Tomb: the Last Days of the Soviet Empire

LENINS TOMB: THE LAST DAYS OF THE SOVIET EMPIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Remnick | 22 pages | 01 Oct 2001 | Random House USA Inc | 9780679751250 | English | New York, United States Lenins Tomb: the Last Days of the Soviet Empire PDF Book Remnick writes after lunching with Ms. The crowds were so dense and chaotic that some people were trampled underfoot, others rammed against traffic lights, and still others choked to death. Mikhail Kalinin tomb. The body lies in a glass case with dim lights. Khrushchev followed by reading a decree ordering the removal of Stalin's remains. Stalin's own grandson, Yevgeny Djugashvili, asked Mr. It's as if the regime were guilty of two crimes on a massive scale: murder and the unending assault against memory. After years of blind obedience and misery, the Soviet people seem to awaken from a miserable dream in the late s and early s. Konstantin Chernenko tomb. It's an absolutely unprecedented, wacky, counterproductive request. Yet even the brief minute or so that visitors are allotted with Lenin leaves a lasting impression. The bodies of Kim and Mao do not look mach different from Lenin although they were embalmed years later. Here is Nina Andreyeva, the famous Stalinist of Leningrad still unrepentant , whose article in the hard-line newspaper Sovetskaya Rossiya, "I Cannot Betray My Principles," seemed a harbinger of a reaction against perestroika. Remnick intrudes a little too much for my taste. Pyongyang is build as a showcase for the North Korean regime, this guide lists many of the giant communist monuments and architecture. -

Glasnost, Perestroika and the Soviet Media Communication and Society General Editor: James Curran

Glasnost, Perestroika and the Soviet Media Communication and Society General editor: James Curran Social Work, the Media and Public Relations Bob Franklin and Dave Murphy What News? The Market, Politics and the Local Press Bob Franklin and Dave Murphy Images of the Enemy: Reporting the New Cold War Brian McNair Pluralism, Politics and the Marketplace: The Regulation of German Broadcasting Vincent Porter and Suzanne Hasselbach Potboilers: Methods, Concepts and Case Studies in Popular Fiction Jerry Palmer Glasnost, Perestroika and the Soviet Media Brian McNair London and New York First published 1991 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006. “ To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 © 1991 Brian McNair All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data McNair, Brian Glasnost, perestroika and the Soviet media. – (Communication and scoiety). 1. Soviet Union. Mass media I. Title II. Series 302.230947 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data McNair, Brian Glasnost, perestroika and the Soviet media / Brian McNair. -

Perestroika and the Decline of Soviet Legitimacy

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1993 Contracts in Conflict: erP estroika and the Decline of Soviet Legitimacy Karl Glenn Hokenmaier Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Hokenmaier, Karl Glenn, "Contracts in Conflict: erP estroika and the Decline of Soviet Legitimacy" (1993). Master's Theses. 775. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/775 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTRACTS IN CONFLICT: PERESTROIKA AND THE DECLINE OF SOVIET LEGITIMACY by Karl Glenn Hokenmaier A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1993 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CONTRACTS IN CONFLICT: PERESTROIKA AND THE DECLINE OF SOVIET LEGITIMACY Karl Glenn Hokenmaier, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1993 Gorbachev’s perception of the Soviet Union’s socio-economic crisis and his subsequent actions to correct the economy and reform the political system were linked with attempts to renegotiate the social contract between the state and the Soviet people. However, reformulation of the social contract was incompatible with the conditions of a second arrangement between the leadership and the nomenklatura-the Soviet ruling class. -

History 38: Russia in the Twentieth Century Spring 2010

HISTORY 38: RUSSIA IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY SPRING 2010 Bob Weinberg Trotter 218 Office Hours: T/TH 1-2 328-8133 W: 1-3 rweinbe1 This course focuses on the major trends and events in Russian history during the twentieth century. Topics include the collapse of the Romanov dynasty, the Bolshevik seizure of power, the fate of the communist revolution, the rise of Stalin, the establishment of the Stalinist system, World War II, de-Stalinization, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. We shall pay particular attention to the interaction between social and economic forces and political policies and explore how the regime’s ideological imperatives and the nature of society shaped the contours of Russia in the twentieth century. Readings include primary documents, historical monographs, oral histories, and literature. Two Six-Page Papers (25 percent each) Final Examination (15 percent) Twelve-Page Research (25 percent) Class Attendance and Active Participation (10 percent) All students are expected to read the College’s policy on academic honesty and integrity that appears in the Swarthmore College Bulletin. The work you submit must be your own, and suspected instances of academic dishonesty will be submitted to the College Judiciary Council for adjudication. When in doubt citing sources, please check with me. I will not accept late papers and will assign a failing grade for the assignment unless you notify me and receive permission from me to submit the paper after the due date. Finally, students are required to attend class on a regular basis in order to pass the course. All documents and articles are on Blackboard (BB). -

1 the Great Communicator and the Beginning of the End of the Cold War1 by Ambassador Eric S. Edelman President Ronald Reagan Is

The Great Communicator and the Beginning of the End of the Cold War1 By Ambassador Eric S. Edelman President Ronald Reagan is known as the “Great Communicator,” a soubriquet that was awarded to him by New York Times columnist Russell Baker, and which stuck despite Reagan’s disclaimer in his farewell address that he “wasn’t a great communicator” but that he had “communicated great things.” The ideas which animated Reagan’s vision were given voice in a series of extraordinary speeches, many of them justly renowned. Among them are his “Time for Choosing” speech in 1964, his “Shining City on a Hill” speech to CPAC in 1974, his spontaneous remarks at the conclusion of the Republican National Convention in 1976 and, of course, his memorable speeches as President of the United States. These include his “Evil Empire” speech to the National Association of Evangelicals, his remarks at Westminster in 1982, his elegiac comments commemorating the 40th anniversary of the D-Day invasion and mourning the Challenger disaster, and his Berlin speech exhorting Mikhail Gorbachev to “Tear Down this Wall” in 1987, which Time Magazine suggested was one of the 10 greatest speeches of all time.2 Curiously, Reagan’s address to the students of Moscow State University during the 1988 Summit with Mikhail Gorbachev draws considerably less attention today despite the fact that even normally harsh Reagan critics hailed the speech at the time and have continued to cite it subsequently. The New York Times, for instance, described the speech as “Reagan’s finest oratorical hour” and Princeton’s liberal historian Sean Wilentz has called it “the symbolic high point of Reagan’s visit…. -

Jacques Vergès, the Devil's Advocate

Jacques Vergès, Devil’s Advocate A Psychohistory of Vergès’ Judicial Strategy Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montreal April 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Civil Law © Jonathan Widell, 2012 Abstract This study undertakes a psychohistory of French criminal defence lawyer Jacques Vergès’ judicial strategy. .His initial articulation of his judicial strategy in his book De la stratégie judiciaire in 1968 continues to inform his legal career, in which he has defended a number of controversial clients, most notably that of Gestapo officer Klaus Barbie in the 1987 trial. Vergès distinguished two types of judicial strategy in his 1968 book: rupture and connivence. Both strategies should be understood out of Vergès’ Marxist influences. This study looks into the coherence of his career in light of his initial articulation of judicial strategy and explores the shift in emphasis of his strategy from the defence of a cause to that of a person. The study adopts a three-level approach. It considers, first, Vergès’ discourse of his strategy, second, the world politics that shaped his discourse, and third, Vergès’ biography. First, Vergès’ strategy grew out of the duality of rupture and connivence and transformed into what we call devil’s advocacy, in which Vergès pits an accused (as an individual) against the justice system. Devil’s advocacy culminated in his defence of Barbie. After his defence of Barbie, Vergès pitted himself against the justice system so that his own notoriety was reflected to his clients rather than the other way around. -

Chronology End of the Cold War in Europe

Chronology End of the Cold War in Europe (This chronology was compiled by the National Security Archive staff in April 1998 for the conference “The End of the Cold War in Europe, 1989: ‘New Thinking’ and New Evidence) 1987 January 12 - Jaruzelski meets with Pope John Paul II in Italy, Jaruzelski's first official visit to the West since the imposition of martial law in Poland. (Dawisha, p. 283, Foreign, p. 300) January 20 - The USSR stops jamming the BBC. (Garthoff, 304) January 21 - The CPSU Politburo discusses withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan. Foreign Minister Shevardnadze advocates only a partial withdrawal and massive support of the Najib regime. Prime Minister Nikolai Ryzhkov categorically demands a complete withdrawal. Gorbachev proposes "to pull it off within two years." (The Archive of Gorbachev Foundation) January 22 - The CPSU Politburo discusses "acceleration" in upgrading the machine- building industries. (The Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation) January 27 - At a meeting of the Central Committee Gorbachev surprises members with his description of the country as being one of "developing socialism," rather than the stock phrase, "developed socialism," and with approvals of "real elections" and secret ballots. This provides an opening wedge for the introduction of democratic procedure. (Matlock, 64; Garthoff, 303) January 29 - The CPSU Politburo holds discussions on the results of the Warsaw conference of CC secretaries of Comecon countries. The participants point at the growing pro-Western orientation of Eastern Europe. Anatoly Dobrynin argues against "over dramatizing the nuances in the behavior of Honecker." Gorbachev agrees that "they should remain friends." (The Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation) February 10 - The USSR announces that it has pardoned 140 prisoners convicted of subversive activities. -

Download Download

A FUTURE FOR SOCIALISM IN THE USSR? Justin Schwartz The fate of socialism is linked to the crisis in the USSR, the first nation to profess socialism as an ideal. But as the Soviet Union prepares to drop "socialist" from its name, ' it is opportune to inquire whether there is a future for socialism in the USSR. Whether we think so, however, depends in part on whether we think it had a past. "Actually existing socialism" - we need a new term, perhaps "formerly existing socialism" - is not socialism as historically understood, for example, by Marx, involving a democratically controlled economy and a state subordinate to society. The Soviet system is not socialist in this sense but is essentially Stalinist, both in its historical origin and its character, involving a command economy and a dictatorial state. The Stalinist system forfeited its moral authority by repressiveness and lost its economic legitimacy by unsuccessfully competing with the West on the consumerist grounds that favour capitalism instead of the democratic ones that favour socialism. Having delivered neither prosperity nor democracy, it is in disintegration. Socialism in the USSR would thus require not reclaiming a lost revolutionary achieve- ment, for, despite the early aspirations of the Bolsheviks, the USSR was never socialist, but a systematic transformation of society, not a restructuring (perestroika) but a revolutionary reconstruction. In a crisis situation prediction is speculative, but the short-term prospects for a socialist reconstruction of Soviet society, in the classical sense of the term, are slim. Such a project finds support in some sectors of an increasingly organized and mobilized working class, at least in the Slavic republics, but Soviet workers are sharply divided along ethnic and national lines. -

Spartacist No. 49-50 Winter 1993-94

SPARTAC) T NUMBER 49-50 ENGLISH EDITION WINTER 1993-94 From Mexico to Europe: A Cry of Rebellion Rumblings in the "New World Disorder" Cordero/Reuters Laurent Rebours January 1994: Chiapas peasant rebellion explodes in Mexico. October 1993: Air France strike faced down government, stirring workers across Europe. See Page 4 W Robin Blick: Soviet Jews and Menshevik Dementia ............ 2 the Struggle for Communism Revolution, Counterrevolution Fake Trotskyists on the Ukraine and the Jewish Question ........ 18 Why They Misuse Trotsky ....... 10 Trotskyism and the Black Struggle in the U.S. On Trotsky's Advocacy of an In Defense of '.... Independent Soviet Ukraine .... 11 Revolutionary Integrationism ... 56 Prometheus Key Trotsky Works Published in Russian for the First Time Research Library Book The Communist International After Lenin ... 38 AUSTRA LlA ... A$2 BRITAIN ... £1 CANADA ... Cdn$2 IRELAND ... IR£1 USA ... US$1.50 2 SPARTACIST Letter Robin Blick: Menshevik Dementia The following exchange was initially intended for puhli achievements of the revolution and its future.' (,Leon Trot cation in Spartacist No. 47-48 (Winter 1992-93). But, as sky Speaks', New York, 1972, pp.158-160) we stated in a notice in that issue, the previously puhlicized This quotation, it is true, says nothing about the necessity tahle of contents was pre-empted hy the puhlication of the of banning all other parties, only of all power remaining documellt approved at the Second Conference of the Inter in the hands of the Bolsheviks (a 'dictatorship of the party', national Communist League. Had we seen at that time not of the Soviets or of the proletariat). -

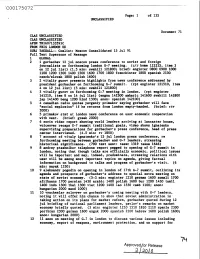

C00175072 Page: 1 of 135 UNCLASSIFIED

C00175072 Page: 1 of 135 UNCLASSIFIED Document 71 CLAS UNCLASSIFIED CLAS UNCLASSIFIED AFSN TB1607133591C FROM FBIS LONDON UK SUBJ TAKEALL-- Comlist: Moscow Consolidated 15 Jul 91 Full Text Superzone of Hessage 1 GLOBAL 2 1 gorbachev 12 jul moscow press conference to soviet and foreign journalists on forthcoming london G-7 meeting. (c/r home 121215, item 3 on 12 jul list) (1.5 min: swahili 121800; brief: enginter 0800 0900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 frenchinter 1800 spanish 2100 czech/slovak 1800 polish 1600) 3 2 vitaliy gurov presents highlights from news conference addressed by president gorbachev on forthcoming G-7 summit. (rpt enginter 121510, item 4 on 12 jul list) (5 min: swabili 121800) 4 3 vitaliy gurov on forthcoming G-7 meeting in london. (rpt enginter 141210, item 8 on 14 jul list) (engna 142300 amharic 141600 swabili 141800 jap 141400 beng 1200 hind 1300; anon: spanish 142100) 5 4 canadian radio quotes yevgeniy primakov saying gorbachev will face "social explosion" if he returns from london empty-handed. (brief: rtv 2000) 6 5 primakov stmt at london news conference on ussr economic cooperation with west. (brief: greek 2000) 7 6 zorin video report showing world leaders arriving at lancaster house, voiceover recaps G-7 summit traditional goals, video shows ignatenko supervizing preparations for gorbachev's press conference, head of press center interviewed. (4.5 min: tv 1800) 8 7 account of vitaly ignatenko's 15 jul london press conference, re forthcoming meeting between gorbachev and G-7 leaders, stressing historical significance. (700 text sent: tassr 1319 tasse 1646) 9 8 andrey ptashnikov telephone report pegged to opening of G-7 summit in london, noting that though talks are' officially economic, political issues will be important and may, indeed, predominate, stressing relations with ussr will be among most important topics on agenda, giving factual information on background to talks and program of gorbachev's visit. -

History 38: Russia in the Twentieth Century Spring 2014 Bob Weinberg

History 38: Russia in the Twentieth Century Spring 2014 Bob Weinberg Office Hours: MW 1-3 Trotter 218 By Appointment 328-8133 rweinbe1 This course focuses on the major trends and events in Russian history during the twentieth century. Topics include the collapse of the Romanov dynasty, the Bolshevik seizure of power, the fate of the communist revolution, the rise of Stalin, the establishment of the Stalinist system, World War II, de-Stalinization, and the legacy of Stalin. We shall pay particular attention to the interaction between social and economic forces and political policies and explore how the regime’s ideological imperatives and the nature of society shaped the contours of Russia in the twentieth century. Readings include primary documents, historical monographs, oral histories, and literature. Two Five-Page Papers (20 percent each) Twelve-Page Research Paper (25 percent) Final Exam (25 percent) Class Attendance and Active Participation (10 percent) All students are expected to read the College’s policy on academic honesty and integrity that appears in the Swarthmore College Bulletin. The work you submit must be your own, and suspected instances of academic dishonesty will be submitted to the College Judiciary Council for adjudication. When in doubt about citing sources, please check with me. I will not accept late papers and will assign a failing grade for the assignment unless you notify me and receive permission from me to submit the paper after the due date. Finally, students are required to attend class on a regular basis in order to pass the course. All documents and articles are on Blackboard (M). -

Breakthrough to Freedom

The International Foundation for SocioEconomic and Political Studies (The Gorbachev Foundation) BREAKTHROUGH TO FREEDOM PERESTROIKA: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS R.VALENT PUBLISHERS 2009 Compiled by Viktor Kuvaldin, Professor, Doctor of History Executive Editor: Aleksandr Veber, CONTENTS Doctor of History Translation: Tatiana Belyak, Konstantin Petrenko To the Reader . .5 Page makeup: Viktoriya Kolesnichenko Art design: R.Valent Publishers PART I. Seven Years that Changed the Country and the World Publisher’s Acknowledgement: Special thanks to Mr. Mikhail Selivanov, Vadim Medvedev. Perestroika’s Chance of Success . .8 who helped make this book possible. Stephen F. Cohen. Was the Soviet System Reformable? . .22 ISBN 9785934392629 Archie Brown. Perestroika and the Five Transformations . .40 Aleksandr Galkin. The Place of Perestroika in the History of Russia . .58 Viktor Kuvaldin. Three Forks in the Road of Gorbachev’s Perestroika . .73 Breakthrough to Freedom. Perestroika: A Critical Analysis. Aleksandr Veber. Perestroika and International Social Democracy . .95 M., R.Valent Publishers, 2009, — 304 pages. Boris Slavin. Perestroika in the Mirror of Modern Interpretations . .111 Jack F. Matlock, Jr. Perestroika as Viewed from Washington, 19851991 . .126 Copyright © 2009 by the International PART II. Our Times and Ourselves Foundation for SocioEconomic and Political Studies (The Gorbachev Foundation) Aleksandr Nekipelov. Is It Easy to Catch a Black Cat in a Dark Room, Copyright © R.Valent Publishers Even If It Is There? . .144 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means Oleg Bogomolov. A Turning Point in History: without written permission of the copyright Reflections of an EyeWitness . .152 holders. Nikolay Shmelev. Bloodshed Is Not Inevitable .