The Camp Ground Excavations - Colne Fen, Earith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Character Assessment

OUSE WASHES Landscape Character Assessment Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES CONTENTS 04 Introduction Annexes 05 Context Landscape character areas mapping at 06 Study area 1:25,000 08 Structure of the report Note: this is provided as a separate document 09 ‘Fen islands’ and roddons Evolution of the landscape adjacent to the Ouse Washes 010 Physical influences 020 Human influences 033 Biodiversity 035 Landscape change 040 Guidance for managing landscape change 047 Landscape character The pattern of arable fields, 048 Overview of landscape character types shelterbelts and dykes has a and landscape character areas striking geometry 052 Landscape character areas 053 i Denver 059 ii Nordelph to 10 Mile Bank 067 iii Old Croft River 076 iv. Pymoor 082 v Manea to Langwood Fen 089 vi Fen Isles 098 vii Meadland to Lower Delphs Reeds, wet meadows and wetlands at the Welney 105 viii Ouse Valley Wetlands Wildlife Trust Reserve 116 ix Ouse Washes 03 THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Context Sets the scene Objectives Purpose of the study Study area Rationale for the Landscape Partnership area boundary A unique archaeological landscape Structure of the report Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Context Ouse Washes LP boundary Wisbech County boundary This landscape character assessment (LCA) was District boundary A Road commissioned in 2013 by Cambridgeshire ACRE Downham as part of the suite of documents required for B Road Market a Landscape Partnership (LP) Heritage Lottery Railway Nordelph Fund bid entitled ‘Ouse Washes: The Heart of River Denver the Fens.’ However, it is intended to be a stand- Water bodies alone report which describes the distinctive March Hilgay character of this part of the Fen Basin that Lincolnshire Whittlesea contains the Ouse Washes and supports the South Holland District Welney positive management of the area. -

LOCATION Earith Lies Along the River Great Ouse with Access Provided by West View Marina

LOCATION Earith lies along the river Great Ouse with access provided by West View Marina. You can travel along the river south-west towards St Ives or northeast towards Ely and Kings Lynn or join the river Cam into Cambridge. The A14 is a short drive away providing easy access into Cambridge, while Huntingdon railway station provides a fast route to Kings Cross. There is also a bus service to St Ives and Cambridge, as well as a long- distance footpath called the Ouse Valley Way, leading to Stretham and St. Ives. Earith Primary School is rated good by Ofsted, and secondary schooling is provided by Abbey College, Ramsey located about 11 miles (17.7 kilometres) away. It is also rated good by Ofsted. Local amenities include a convenience store/post office, vehicle repair garage, part-time doctors' surgery, and a tandoori takeaway. Earith has one public house, The Crown. ENTRANCE HALL Electric storage heater, airing cupboard. LIVING/DINING ROOM 17' 0" x 14' 0" (5.18m x 4.27m) Windows to rear, re-fitted French doors to garden, windows to side, electric storage heater. KITCHEN 14' 0" x 10' 0" (4.27m x 3.05m) Double glazed windows to side (installed 2019). Fitted with range of base and eye level units with work surface over, one and a half bowl sink and drainer unit, built-in electric oven and halogen hob, space for tumble dryer or dishwasher (with plumbing), washing machine and under counter fridge, intercom receiver. BEDROOM ONE 16' 0" x 14' 0" (4.88m x 4.27m) Re-fitted window to front, dressing area with a range of fitted wardrobes, electric storage heater. -

NOTICE of POLL Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF POLL Huntingdonshire District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Bluntisham Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of Parish Councillors for Bluntisham will be held on Thursday 7 May 2015, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Parish Councillors to be elected is eleven. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BERG 17 Sumerling Way, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Mark Bluntisham, Huntingdon, Cambs, PE28 3XT CURTIS Patch House, 2, Colne Richard I Saltmarsh (+) David W.H. Walton (++) Cynthia Jane Road, Bluntisham, Cambridge, PE28 3LT FRANCIS 1 Laxton Grange, John R Bloor (+) Robin C Carter (++) Mike Bluntisham, Cambs, PE28 3XU GORE 38 Wood End, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Rob Bluntisham, Huntingdon GUTTERIDGE 29 St. Mary's Close, Donald R Rhodes (+) Patricia F Rhodes (++) Joan Mary Bluntisham, Huntingdon, Camb's., PE28 3XQ HALL 7 Laxton Grange, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Jo Bluntisham, Huntingdon, PE28 3XU HIGHLAND 7 Blackbird St, Potton, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Steve Beds, SG19 2LT HIGHLAND 7 Blackbird Street, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Tom Potton, Sandy, Beds, SG19 2LT HOPE 15 St Mary's Close., Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Philippa Bluntisham, -

5 – 7 High Street, Earith Cambridgeshire

5 – 7 HIGH STREET, EARITH CAMBRIDGESHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Report Number: 1053 May 2014 5 – 7 HIGH STREET, EARITH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Prepared for: Jeremy Hanncok J T Hancock and Associates Ltd On behalf of: Roundwood Restorations Ltd Roundwood Farm Stutton Ipswich Suffolk IP9 2SY By: Martin Brook BA PIfA Britannia Archaeology Ltd 115 Osprey Drive, Stowmarket, Suffolk, IP14 5UX T: 01449 763034 [email protected] www.britannia-archaeology.com Registered in England and Wales: 7874460 May 2014 Site Code ECB4169 NGR TL 3875 7490 Planning Ref. 1201542FUL OASIS Britanni1-178984 Approved By: Tim Schofield Date May 2014 © Britannia Archaeology Ltd 2014 all rights reserved Report Number 1053 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation Project Number 1056 CONTENTS Abstract 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Site Description 3.0 Planning Policies 4.0 Archaeological Background 5.0 Project Aims 6.0 Project Objectives 7.0 Fieldwork Methodology 8.0 Presentation of Results 9.0 Deposit Model 10.0 Discussion & Conclusion 11.0 Project Archive & Deposition 12.0 Acknowledgments Bibliography Appendix 1 Deposit Tables and Feature Descriptions Appendix 2 Specialist Reports Appendix 3 Concordance of Finds Appendix 4 OASIS Sheet Figure 1 Site Location Plan 1:500 Figure 2 CHER Entries Plan 1:10,000 Figure 3 Feature Plan 1:200 Figure 4 Plans, Sections and Photographs 1:100 & 1:20 Figure 5 Sample Sections and Photographs 1:20 1 ©Britannia Archaeology Ltd 2014 all rights reserved Report Number 1053 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation Project Number 1056 Abstract In April 2014 Britannia Archaeology Ltd (BA) undertook an archaeological trial trench evaluation on land at 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire (NGR TL 3875 7490) in response to a design brief issued by Cambridgeshire County Council, Historic Environment Team. -

Earith Conservation Area Character Assessment June 2008 This Document Was Adopted by the Council’S Cabinet on 12Th June 2008 Contents

Earith Conservation Area Character Assessment June 2008 This document was adopted by the Council’s Cabinet on 12th June 2008 Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 3. 1. Introduction, Statement of Significance & Historical Development ........................ 4. Maps: 1. The Geographical Setting of Earith within Huntingdonshire ........................................ 4. 2. Aerial Photograph showing Earith Conservation Area ................................................ 5. 3. 1880s Historic Map of Earith ....................................................................................... 7. 2. The Analysis of the Conservation Area ...................................................................... 8. Table: 1. Localities and Neighbourhoods within the Conservation Area .................................... 9. Maps: 4. The Conservation Area and its Sub Divisions ............................................................. 10. 5. Locality 2 Settlement Character Analysis .................................................................... 12. 6. Locality 1 Settlement Character Analysis .................................................................... 14. 7. Locality 2a Settlement Character Analysis .................................................................. 15. Earith Building Type Analysis .......................................................................................... 17. Earith Building Details and Materials ............................................................................. -

Tokens Found in Haddenham, Cambridgeshire, and a Seventeenth-Century Issuer

TOKENS FOUND IN HADDENHAM, CAMBRIDGESHIRE, AND A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ISSUER M.J. BONSER AND R.H. THOMPSON, with contributions by C.F. BESTER THE Revd. William Cole, the Cambridge antiquary (1714-82), owned extensive property in Haddenham in the south-west of the Isle of Ely, and two tokens found there are illustrated and described in vol. 32 of his manuscript collections.1 A. Garden of William Symonds, -1768. The first 'was dug up in a Garden belonging to me at Hadenham in the Isle of Ely, & given to me by my Tenant Wm Symonds in January 1768'. The second was 'found at Hadenham & given me as above 1768'. The wording in both cases leaves the date of finding open to doubt, but if not actually in 1768 it was presumably not long before. Cole's father had purchased several hundred acres including five tenements, to which the antiquary himself added two closes;- and the location of William Symonds's garden must remain uncertain, although it was probably in the hamlet of Aldreth, adjoinjng Ewell Fen in which Cole's farm Frog Hall was situated (a farmhouse and several cottages in Aldreth were associated with Frog Hall Farm until about 1944). 1. Nuremberg Rechenmeister jetton or Schulpfennig; second half of the sixteenth century. Similar to No. 20 below, but alphabet with G reversed and no additional letters; not illustrated. 2. Seventeenth-century token; c. 1660. Obv. IAMES PARTRICH OF around a mitre; surname appears as 'RICH'. Rev. ROOYSTON VINTNER around letter P above IC. Williamson,3 Hertfordshire 165 or 166; probably 165, on which a flaw developed across the first part of the surname; not illustrated. -

The Ouse Washes

NRA Anglii j i t - u THE OUSE WASHES “The Ouse Washes offer a rich variety of experiences both as an internationally important wildlife site and its continuing role of protecting the fens from flooding. ” O wildlife RSPB NRA National Rivers Authority Anglian Region THE ANGLIAN REGION The Anglian Region hosts a rich variety of wildlife habitats, flora and landscapes associated with its streams, rivers, ponds, lakes, wetlands, estuaries and coastal waters. Many of these are protected by statutory designations, for example, 75% of the coastline is covered by a conservation and/or landscape designation. Five Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty fall either partially or wholly within Anglian Region, along with England's newest National Park - the Broads. A fifth of England and Wales internationally important wetlands, from large estuaries such as the Humber and the Wash, to Ouse Washes in flood washlands such as the Ouse Washes, occur within this region. THE OUSE WASHES - FLOOD DEFENCE IMPORTANCE The Middle and South Level Barrier Banks contain Bedford Ouse flood flows within the Ouse Washes and are therefore vital for the flood protection of the Cambridgeshire Fens. Complete towns, villages and isolated dwellings, Flood waters are able to flow throigh \ together with approximately 29,000 the Hundred Foot River when pean " hectatres of agricultural land are protected from flooding by the Ouse When the peak flood has passed, i Washes Defences. Washes and back into the Old Failure of the South Level Barrier Bank would cause over 230 residential properties to be flooded to depths of up to 1.8m. As much as 11,000 hectares of Flooded washland and ditches agricultural land would be flooded. -

Baptist History First Sermon at Somersham Baptist Church Coxe

Baptist History http://www.baptisthistory.org.uk/basicpage.php? contents=home&page_title=Home%20Page First sermon at Somersham Baptist Church Mr Fuller, of Kettering, preached an excellent sermon at Bluntisham the preceding evening, and the next morning a very encouraging one at Somersham, from Zech. iv. 10, 'Who hath despised the day of small things ? ' The congregation was so large in the afternoon, that it was thought expedient to have the service in a close. Mr Ragsdell, of Thrapston, preached from Matt. vi. 10, ' Thy Kingdom come.' The sermon in the evening was by Mr Edmonds, of Cambridge, from Psalm Ixxiv. 21, ' Arise, God, plead thine own cause.'" Coxe Feary and the awakening in Bluntisham FROM "A CLOUD OF WITNESSES" BY MICHAEL HAYKIN IN THE EVANGELICAL TIMES ONLINE; MARCH 2002 REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION Coxe Feary (1759-1822) sustained a long pastorate in the village of Bluntisham, about fifteen miles north of Cambridge, England. He was raised in the Church of England, but during his teens became dissatisfied with the irreligious conduct of worshippers at the parish church. He considered attending a Baptist church in a nearby village — perhaps the work at Needingworth, which had been founded in 1767. But he found the church consisted of ‘narrow-minded’ hyper-Calvinists, who pronounced ‘destruction on all who did not believe their creed’. For a while he attended a Quaker congregation in Earith, another nearby village, because their views accorded with his belief in the freedom of the human will and the saving merit of good works. CONVERSION In 1780 he read James Hervey’s Theron and Aspasio (1755), a massive defence of Calvinism. -

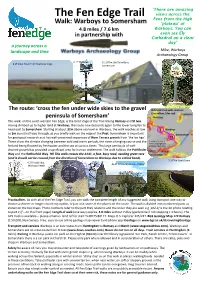

The Fen Edge Trail Walk

’There are amazing The Fen Edge Trail views across the Fens from the high Walk: Warboys to Somersham ’plateau’ at 4.8 miles / 7.6 km Warboys. You can in partnership with even see Ely Cathedral on a clear day’ a journey across a Mike, Warboys landscape and time Archaeology Group 15.2f Somersham 2.1f Warboys 15.1f The Old Tithe Barn, 4.4f View down from Warboys ridge Somersham The route: ‘cross the fen under wide skies to the gravel Hillshade map with contours peninsula of Somersham’ (5m yellow, 10m red) This walk, on the south western Fen Edge, is the third stage of the Trail linking Ramsey and St Ives. Having climbed up to higher land at Warboys, the route now descends again to the lower lying fen to Warboys head east to Somersham. Starting at about 32m above sea level in Warboys, the walk reaches as low 1 as 1m about half way through, as you briefly walk on the edge of the Peat. Somersham is important Somersham for geological research as it has well-preserved sequences of River Terrace gravels from ‘the Ice Age’. 15 These show the climate changing between cold and warm periods, the rivers changing course and the Contains OS data © Crown copyright and fenland being flooded by freshwater and the sea at various times. This large peninsula of well- database right 2014 drained gravels has provided a significant area for human settlement. The walk follows the Pathfinder Way and the Rothschild Way. NB This walk crosses the A141, a fast, busy road, needing great care (and it should not be crossed from the direction of Somersham to Warboys due to a blind bend). -

Special Collections Online

HUNTINGDONSHIRE. J TRADES. BOO 99 Day John, Holywell, St. Ives Potto Carter Henry, Filbert walk, Hem- BI.ACKSMITHS. Day William, Cambridge st. St. Neots ingford Grey, St. Ives See Smiths, Blacksmiths & Farriers. Dean Fred, Broughton, Huntingdon PottB Fred, New town, Ramsey,Hntngdn Dew John, Gt. Whyte,Ramsey,Huntngdn Poulter L. Great Ra.veley, Huntingdon BOAT OWNERS. ~g Snarey, Woodhurst, Hunti~gdon Prior John, Colne, St. Ives . Chopping Arthur, Houghton, Huntingdon Duon_ Waiter, Brampton, lluntmgdon Ransome S_al?son S. Drampton,lluntmgdn Corbey & Hmlkle, River terrace, St. Neots D~wmng Chas. Hy.Old Weston,H~ntngdn Rayner William, Oundle road, Woodston, DooThos.(pleasure),Wellington st. St.Ives Dring Jesse, Fen, Wa.rboys, Huntmgdon · Peterborough Gale Wm. (pleasure), Broadway, St. Ives Dring Wm. Hollow, Ramsey, Huntingdon Richards John Herbert, West $t. St. Ives Gore Hy. (pleasure), Broadway, St. Ives Durham John, Huntingdon st. St. ~eots Ro~rts William, Fenstanton, St. Ives Metoalfe Thomas Arth.Holywell, St. Ives Edwards W.Ramsey St.Mary's,Huntmgdn Robms Charles, Market square, St. Neots Potts J. The Field Ramsey Huntingdon Ellis John William, Bluntisham, St. Ives Robinson Daniel, Warboys, Huntingdon ' ' Emerson William, Fenstanton, St. Tves Royston William, Colne, St. Ives BOAT & BARGE BUILDERS. Emmington Robert, Ramsey St. Mary's, Royston William, Fenstanton, St. Ives Childs & Hall, Ouse villa, Godmanchester, Huntingdon Scott David Richard, 132 Belsize avenue, Huntingdon Enfield Joseph, Bluntisham, St. Ives Woodston, Peterborough Giddins & Son, Hemingford Grey, St. Ives Fletcher William, Great Whyte, Ramsey, Sellers W.South st.Stanground, Peterboro' Starling W. H. Stanground, Peterborough Huntingdon Seymour Bert, Colne, St. Ives 1 Flint John Wm. Agden Green, St. -

Services Directory for Older People in St. Ives and Huntingdon

Services Directory for Older People in St. Ives and Huntingdon Huntingdonshire Older People’s Mental Health Primary Care Service 1 This catalogue of day services, activities and opportunities for older people in the St. Ives and Huntingdonshire locality is designed to offer an insight into the possibilities available to them in their area. Although it was up to date on its initial publication, there is no guarantee that these services will remain in place on a long term basis. Some services have been running for many years and will continue to do so but the Foundation Trust does not guarantee that this catalogue will remain accurate although endeavours will be made to revise the edition on a regular basis. If individuals become aware of new services or changes to services described in this catalogue, the Trust would be grateful if service users could inform us, please email: [email protected] . It should be noted that services within this publication generally have a good reputation for the quality of their service provision but the Trust does not recommend any service or accept responsibility for difficulties found within these services. Updated March 2012 (This document is based on an original document created by Wendy Llaneza) 2 Table of Contents Page Day Centres 4 Educational and Learning Opportunities 5 Clubs and Societies 6 Fitness, Health & Well-Being 12 Churches, Religion and Church Based Activities 14 Charities and Voluntary Agencies 15 Volunteering Opportunities 16 Carers Opportunities and Support 16 Transport 17 Other -

Huntingdonshire. St

- DIRECTORY.] HUNTINGDONSHIRE. ST. IVES. 49 7.30 & 11.15 a.m. 12.5,3,5.15 & 8.5 p.m.; Railway station, Officers. 7.20, 11.5 & 11.55 a.m. 2.55, 5 & 7.55 p.m Clerk for Highway Purposes, Wm. Arthur Watts, Broadway Parcels can be posted until 12.20 p.m. & 8.30 p.m. (sun Clerk for Sanitary Purposes, George Dennis Day M.A., LL.B. days exce-pted) Broadway Town Deliveries.-Letters & Parcels.-lst delivery at 7 a.m. ; Treasurer for Sanitary Purposes, George Edward Foster, 2nd a.t 8.30 a.m.; extra parcel delivery, 9.40 a.m.; 3rd banker, Cambridge at 2.35 p.m. ; 4th at 5.20 p.m.; on sundays, the first delivery Treasurer for Highway Purposes, C. P. Tebbutt, Cambridge of letters only is made & Cambridgeshire Bank, Pavement Medical Officer of Health, B. Anningson M.A., M.D. Waltham. COUNTY MAGISTRATES FOR HURSTINGSTONE sal, Barton road, Cambridge PETTY SESSIONAL DIVISION. Surveyors, Thomas Bassett, Fenstanton & H. W. Saunders, Geldart Henry Charles e~q. M.A., D.L. Walden house, Hunt- Raveley ingdon, chairman Sanitary Inspector, John Archer, Hemingford Abbots Bevan Ernest George esq. M.A. Hemingford Grey, St. Ives Brown Bateman esq. Bridge house, Huntingdon PUBLIC ESTABLISHMENTS. Coote Howard esq. D.L. The Rookery, Fenstanton, St. Ives Corporation Fire Brigade; engine house, East st.; Frederick Coote Thomas esq. D.L. Oaklands, Fenstanton, St. Ives Giddings, superintendent & 8 men; keys at Mr Giddings', Goodman Henry esq. Witton house, St. Ives North road & all firemen Green John George esq. Birchdene, Houghton, Huntingdon Cemetery, J.