Great Ouse Valley Flood Plain Meadows Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Environment Strategy

OUR ENVIRONMENT, OUR FUTURE THE REGIONAL ENVIRONMENT STRATEGY FOR THE EAST OF ENGLAND Produced by a joint working group representing The East of England Regional Assembly and The East of England Environment Forum JULY 2003 ‘OUR ENVIRONMENT, OUR FUTURE’ THE REGIONAL ENVIRONMENT STRATEGY FOR THE EAST OF ENGLAND PRODUCED BY A JOINT WORKING GROUP REPRESENTING THE EAST OF ENGLAND REGIONAL ASSEMBLY AND THE EAST OF ENGLAND ENVIRONMENT FORUM JULY 2003 FOREWORD This first Environment Strategy for the East of England region catalogues and celebrates the many diverse environmental assets which will have a crucial bearing on the continued economic and social development of the Region. This Strategy will complement the other regional strategies within the Regional Assembly’s family of ‘Integrated Regional Strategies’. It deliberately makes key linkages between the environmental assets of the region, and economic development and social inclusion. The delivery of the Strategy will be the responsibility of Government, local authorities and other public and private sector bodies, and the voluntary sector. Crucially, everyone who lives and works in the East of England and values the region as a diverse natural and built Further Information landscape, is an important stakeholder. The very act of producing the Strategy has raised many issues, challenges and missing If you have questions about the Regional Environment Strategy, or would like to find out linkages. We hope above all that the Strategy will assist our regional partners in focussing more about how the region is moving towards a more sustainable future, please contact: environmental consciousness at the forefront of other strands of public policy making. -

River Great Ouse Pavenham

RIVER GREAT OUSE SDAA controls the fishing rights on four separate stretches of the Great Ouse. Each stretch has very different characteristics, which adds further variety to the waters the club has to offer. Pavenham is located on the iconic ‘Ouse above Bedford’, famous for its barbel and chub fishing. The relatively short stretch of river at Willington is located on the navigable section downstream of Bedford where chub are the dominant species, but with a good mix of other species that provide reliable sport throughout the year. Finally the club controls two sections at either end of St Neots. SDAA has recently acquired the fishing rights on a 350 yard section behind Little Barford power station renowned as an excellent mixed fishery. At the downstream end of St Neots the club has over 2 miles of fishing at Little Paxton including a large weirpool, deep slow moving stretches and shallower faster flowing sections that contain a wide variety of species, many to specimen proportions and including a good head of double figure barbel. PAVENHAM The mile of available river bank at Pavenham has a variety of depths and flow, typical of the Ouse upstream of Bedford. With a walk of at least 400 yards from the parking areas it pays to travel light. This also ensures the venue is never crowded and several swims can be ‘primed’ and fished during the day. Although not present in quite the same numbers as a few years back, barbel well into double figures are caught each season. However, most barbel anglers are rather secretive about their catches and only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ is ever reported. -

Landscape Character Assessment

OUSE WASHES Landscape Character Assessment Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES CONTENTS 04 Introduction Annexes 05 Context Landscape character areas mapping at 06 Study area 1:25,000 08 Structure of the report Note: this is provided as a separate document 09 ‘Fen islands’ and roddons Evolution of the landscape adjacent to the Ouse Washes 010 Physical influences 020 Human influences 033 Biodiversity 035 Landscape change 040 Guidance for managing landscape change 047 Landscape character The pattern of arable fields, 048 Overview of landscape character types shelterbelts and dykes has a and landscape character areas striking geometry 052 Landscape character areas 053 i Denver 059 ii Nordelph to 10 Mile Bank 067 iii Old Croft River 076 iv. Pymoor 082 v Manea to Langwood Fen 089 vi Fen Isles 098 vii Meadland to Lower Delphs Reeds, wet meadows and wetlands at the Welney 105 viii Ouse Valley Wetlands Wildlife Trust Reserve 116 ix Ouse Washes 03 THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Context Sets the scene Objectives Purpose of the study Study area Rationale for the Landscape Partnership area boundary A unique archaeological landscape Structure of the report Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Context Ouse Washes LP boundary Wisbech County boundary This landscape character assessment (LCA) was District boundary A Road commissioned in 2013 by Cambridgeshire ACRE Downham as part of the suite of documents required for B Road Market a Landscape Partnership (LP) Heritage Lottery Railway Nordelph Fund bid entitled ‘Ouse Washes: The Heart of River Denver the Fens.’ However, it is intended to be a stand- Water bodies alone report which describes the distinctive March Hilgay character of this part of the Fen Basin that Lincolnshire Whittlesea contains the Ouse Washes and supports the South Holland District Welney positive management of the area. -

LOCATION Earith Lies Along the River Great Ouse with Access Provided by West View Marina

LOCATION Earith lies along the river Great Ouse with access provided by West View Marina. You can travel along the river south-west towards St Ives or northeast towards Ely and Kings Lynn or join the river Cam into Cambridge. The A14 is a short drive away providing easy access into Cambridge, while Huntingdon railway station provides a fast route to Kings Cross. There is also a bus service to St Ives and Cambridge, as well as a long- distance footpath called the Ouse Valley Way, leading to Stretham and St. Ives. Earith Primary School is rated good by Ofsted, and secondary schooling is provided by Abbey College, Ramsey located about 11 miles (17.7 kilometres) away. It is also rated good by Ofsted. Local amenities include a convenience store/post office, vehicle repair garage, part-time doctors' surgery, and a tandoori takeaway. Earith has one public house, The Crown. ENTRANCE HALL Electric storage heater, airing cupboard. LIVING/DINING ROOM 17' 0" x 14' 0" (5.18m x 4.27m) Windows to rear, re-fitted French doors to garden, windows to side, electric storage heater. KITCHEN 14' 0" x 10' 0" (4.27m x 3.05m) Double glazed windows to side (installed 2019). Fitted with range of base and eye level units with work surface over, one and a half bowl sink and drainer unit, built-in electric oven and halogen hob, space for tumble dryer or dishwasher (with plumbing), washing machine and under counter fridge, intercom receiver. BEDROOM ONE 16' 0" x 14' 0" (4.88m x 4.27m) Re-fitted window to front, dressing area with a range of fitted wardrobes, electric storage heater. -

NOTICE of POLL Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF POLL Huntingdonshire District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Bluntisham Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of Parish Councillors for Bluntisham will be held on Thursday 7 May 2015, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Parish Councillors to be elected is eleven. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BERG 17 Sumerling Way, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Mark Bluntisham, Huntingdon, Cambs, PE28 3XT CURTIS Patch House, 2, Colne Richard I Saltmarsh (+) David W.H. Walton (++) Cynthia Jane Road, Bluntisham, Cambridge, PE28 3LT FRANCIS 1 Laxton Grange, John R Bloor (+) Robin C Carter (++) Mike Bluntisham, Cambs, PE28 3XU GORE 38 Wood End, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Rob Bluntisham, Huntingdon GUTTERIDGE 29 St. Mary's Close, Donald R Rhodes (+) Patricia F Rhodes (++) Joan Mary Bluntisham, Huntingdon, Camb's., PE28 3XQ HALL 7 Laxton Grange, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Jo Bluntisham, Huntingdon, PE28 3XU HIGHLAND 7 Blackbird St, Potton, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Steve Beds, SG19 2LT HIGHLAND 7 Blackbird Street, Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Tom Potton, Sandy, Beds, SG19 2LT HOPE 15 St Mary's Close., Robin C Carter (+) Michael D Francis (++) Philippa Bluntisham, -

T1)E Bedford,1)Ire Naturaii,T 45

T1)e Bedford,1)ire NaturaIi,t 45 Journal for the year 1990 Bedfordshire Natural History Society 1991 'ISSN 0951 8959 I BEDFORDSHffiE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY 1991 Chairman: Mr D. Anderson, 88 Eastmoor Park, Harpenden, Herts ALS 1BP Honorary Secretary: Mr M.C. Williams, 2 Ive! Close, Barton-le-Clay, Bedford MK4S 4NT Honorary Treasurer: MrJ.D. Burchmore, 91 Sundon Road, Harlington, Dunstable, Beds LUS 6LW Honorary Editor (Bedfordshire Naturalist): Mr C.R. Boon, 7 Duck End Lane, Maulden, Bedford MK4S 2DL Honorary Membership Secretary: Mrs M.]. Sheridan, 28 Chestnut Hill, Linslade, Leighton Buzzard, Beds LU7 7TR Honorary Scientific Committee Secretary: Miss R.A. Brind, 46 Mallard Hill, Bedford MK41 7QS Council (in addition to the above): Dr A. Aldhous MrS. Cham DrP. Hyman DrD. Allen MsJ. Childs Dr P. Madgett MrC. Baker Mr W. Drayton MrP. Soper Honorary Editor (Muntjac): Ms C. Aldridge, 9 Cowper Court, Markyate, Herts AL3 8HR Committees appointed by Council: Finance: Mr]. Burchmore (Sec.), MrD. Anderson, Miss R. Brind, Mrs M. Sheridan, Mr P. Wilkinson, Mr M. Williams. Scientific: Miss R. Brind (Sec.), Mr C. Boon, Dr G. Bellamy, Mr S. Cham, Miss A. Day, DrP. Hyman, MrJ. Knowles, MrD. Kramer, DrB. Nau, MrE. Newman, Mr A. Outen, MrP. Trodd. Development: Mrs A. Adams (Sec.), MrJ. Adams (Chairman), Ms C. Aldridge (Deputy Chairman), Mrs B. Chandler, Mr M. Chandler, Ms]. Childs, Mr A. Dickens, MrsJ. Dickens, Mr P. Soper. Programme: MrJ. Adams, Mr C. Baker, MrD. Green, MrD. Rands, Mrs M. Sheridan. Trustees (appointed under Rule 13): Mr M. Chandler, Mr D. Green, Mrs B. -

5 – 7 High Street, Earith Cambridgeshire

5 – 7 HIGH STREET, EARITH CAMBRIDGESHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Report Number: 1053 May 2014 5 – 7 HIGH STREET, EARITH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION Prepared for: Jeremy Hanncok J T Hancock and Associates Ltd On behalf of: Roundwood Restorations Ltd Roundwood Farm Stutton Ipswich Suffolk IP9 2SY By: Martin Brook BA PIfA Britannia Archaeology Ltd 115 Osprey Drive, Stowmarket, Suffolk, IP14 5UX T: 01449 763034 [email protected] www.britannia-archaeology.com Registered in England and Wales: 7874460 May 2014 Site Code ECB4169 NGR TL 3875 7490 Planning Ref. 1201542FUL OASIS Britanni1-178984 Approved By: Tim Schofield Date May 2014 © Britannia Archaeology Ltd 2014 all rights reserved Report Number 1053 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation Project Number 1056 CONTENTS Abstract 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Site Description 3.0 Planning Policies 4.0 Archaeological Background 5.0 Project Aims 6.0 Project Objectives 7.0 Fieldwork Methodology 8.0 Presentation of Results 9.0 Deposit Model 10.0 Discussion & Conclusion 11.0 Project Archive & Deposition 12.0 Acknowledgments Bibliography Appendix 1 Deposit Tables and Feature Descriptions Appendix 2 Specialist Reports Appendix 3 Concordance of Finds Appendix 4 OASIS Sheet Figure 1 Site Location Plan 1:500 Figure 2 CHER Entries Plan 1:10,000 Figure 3 Feature Plan 1:200 Figure 4 Plans, Sections and Photographs 1:100 & 1:20 Figure 5 Sample Sections and Photographs 1:20 1 ©Britannia Archaeology Ltd 2014 all rights reserved Report Number 1053 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation Project Number 1056 Abstract In April 2014 Britannia Archaeology Ltd (BA) undertook an archaeological trial trench evaluation on land at 5 – 7 High Street, Earith, Cambridgeshire (NGR TL 3875 7490) in response to a design brief issued by Cambridgeshire County Council, Historic Environment Team. -

This Timetable Runs on New Year's Eve Only

Cambridge • St Neots • Bedford • Milton Keynes • Buckingham • Bicester • Oxford NEW YEAR’S EVE Cambridge Parkside bay 16 0710 0740 0810 40 10 Madingley Road Park & Ride bay 2 0722 0752 0822 52 22 Loves Farm Cambridge Road 0740 0810 0840 10 40 St Neots Cambridge Street 0743 0813 0843 13 43 St Neots Market Square stop D arr. 0750 0820 0850 20 50 same coach - no need to change St Neots Market Square stop D dep. 0750 0820 0850 20 50 Eaton Socon Field Cottage Road 0754 0824 0854 24 54 Great Barford Golden Cross 0801 0831 0901 THEN 31 01 Goldington Green Barkers Lane 0811 0841 0911 AT 41 11 Bedford Bus Station stop N arr. 0819 0849 0919 THESE 49 19 TIMES UNTIL Bedford stop N 0430 0500 0530 0600 0630 0700 0730 0800 0830 0900 0930 00 320 Bus Station dep. PAST Milton Keynes Coachway bay 1 arr. 0456 0526 0556 0626 0656 0726 0756 0826 0856 0926 0956 EACH 26 56 same coach - no need to change HOUR Milton Keynes Coachway bay 1 dep. 0501 0531 0601 0631 0701 0731 0801 0831 0901 0931 1001 31 01 Central Milton Keynes stop H4 0513 0543 0613 0643 0713 0743 0813 0843 0913 0943 1013 43 13 Milton Keynes Rail Station stop Z4 0525 0555 0625 0655 0725 0755 0825 0855 0925 0955 1025 55 25 Buckingham High Street bus stand arr. 0547 0617 0647 0717 0747 0817 0847 0917 0947 1017 1047 17 47 same coach - no need to change Buckingham High Street bus stand dep. 0547 0617 0647 0717 0747 0817 0847 0917 0947 1017 1047 17 47 Bicester Bus Station stand 3 0515 0645 0715 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 1115 45 15 Oxford Bus Station stop 11 0645 0715 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 1115 1145 15 45 NEW YEAR’S EVE Cambridge Parkside bay 16 1440 1510 1540 1610 1710 1725 1740 1810 1840 1910 1940 2010 2030 Madingley Road Park & Ride bay 2 1452 1522 1552 1622 1722 1737 1752 1822 1852 1922 1952 2022 2042 Loves Farm Cambridge Road 1510 1540 1610 1640 1740 1755 1810 1840 1910 1940 2010 2040 2100 St Neots Cambridge Street 1513 1543 1613 1643 1743 1758 1813 1843 1913 1943 2013 2043 2103 St Neots Market Square stop D arr. -

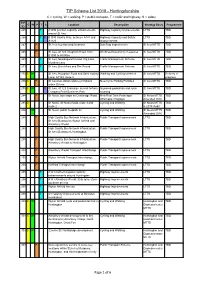

TIP Scheme List 2018 - Huntingdonshire C = Cycling, W = Walking, P = Public Transport, T = Traffic and Highway, S = Safety

TIP Scheme List 2018 - Huntingdonshire C = cycling, W = walking, P = public transport, T = traffic and highway, S = safety TIP C W P T S Location Description Strategy Basis Programme ID 265 T A1096 junction capacity enhancements Highway Capacity Improvements LTTS TBD around St Ives 266 T S B1090 Sawtry Way, between A141 and Highway Capacity and Safety LTTS TBD A1123 Improvements 267 P St. Ives key bus stop locations Bus Stop improvement St Ives MTTS TBD 268 P St Ives, A1123 Houghton Road, from On Street bus priority measures St Ives MTTS TBD B1090 to Hill Rise 269 T St Ives; Needingworth Road, Pig Lane, Traffic Management Scheme St Ives MTTS TBD Meadow Lane 271 T St Ives; Burstellars and The Pound Traffic Management Scheme St Ives MTTS TBD 273 C W St Ives, Houghton Road and Saint Audrey Walking and Cycling schemes St Ives MTTS Delivery in Lane, A1123, route 3 progress 276 C P St Ives bus station and key locations New Cycle Parking Facilities St Ives MTTS TBD within St Ives 278 C W S St Ives, A1123 Crossing - access to/from Improved pedestrian and cycle St Ives MTTS TBD Compass Point Business Park crossing 284 P St Neots, bus stops on Cambridge Road New Real Time Passenger St Neots MTTS TBD Information Displays Amended 2016 285 C St Neots, St Neots Road, route 3 and Cycling and Walking St Neots MTTS TBD route 2 & LSTF Audit 286 W St Neots, public footpath 32 Cycling and Walking St Neots MTTS TBD Amended 2016 288 P High Quality Bus Network Infrastructure, Public Transport Improvement LTTS TBD St Ives (Busway) to Wyton Airfield and Alconbury Weald 289 P High Quality Bus Network Infrastructure, Public Transport Improvement LTTS TBD St Ives (Busway) to Huntingdon. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Ecological Changes in the British Flora WALKER, KEVIN,JOHN How to cite: WALKER, KEVIN,JOHN (2009) Ecological Changes in the British Flora, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/121/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Ecological Changes in the British Flora Kevin John Walker B.Sc., M.Sc. School of Biological and Biomedical Sciences University of Durham 2009 This thesis is submitted in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dedicated to Terry C. E. Wells (1935-2008) With thanks for the help and encouragement so generously given over the last ten years Plate 1 Pulsatilla vulgaris , Barnack Hills and Holes, Northamptonshire Photo: K.J. Walker Contents ii Contents List of tables vi List of figures viii List of plates x Declaration xi Abstract xii 1. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2017-2018

The Wildlife Trust BCN Annual Report and Accounts 2017-2018 Some of this year’s highlights ___________________________________________________ 3 Chairman’s Introduction _______________________________________________________ 5 Strategic Report Our Five Year Plan: Better for Wildlife by 2020 _____________________________________ 6 Delivery: Wildlife Conservation __________________________________________________ 7 Delivery: Nene Valley Living Landscape _________________________________________________ 8 Delivery: Great Fen Living Landscape __________________________________________________ 10 Delivery: North Chilterns Chalk Living Landscape ________________________________________ 12 Delivery: Ouse Valley Living Landscape ________________________________________________ 13 Delivery: Living Landscapes we are maintaining & responsive on ____________________________ 14 Delivery: Beyond our living landscapes _________________________________________________ 16 Local Wildlife Sites _________________________________________________________________ 17 Planning __________________________________________________________________________ 17 Monitoring and Research ____________________________________________________________ 18 Local Environmental Records Centres __________________________________________________ 19 Land acquisition and disposal _______________________________________________________ 20 Land management for developers _____________________________________________________ 21 Reaching out - People Closer to Nature __________________________________________ -

Cambridgeshire Green Infrastructure Strategy

Cambridgeshire Green Infrastructure Strategy Page 1 of 176 June 2011 Contributors The Strategy has been shaped and informed by many partners including: The Green Infrastructure Forum Anglian Water Cambridge City Council Cambridge Past, Present and Future (formerly Cambridge Preservation Society) Cambridge Sports Lake Trust Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Biodiversity Partnership Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Environmental Record Centre Cambridgeshire County Council Cambridgeshire Horizons East Cambridgeshire District Council East of England Development Agency (EEDA) English Heritage The Environment Agency Fenland District Council Forestry Commission Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group GO-East Huntingdonshire District Council Natural England NHS Cambridgeshire Peterborough Environment City Trust Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) South Cambridgeshire District Council The National Trust The Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire & Peterborough The Woodland Trust Project Group To manage the review and report to the Green Infrastructure Forum. Cambridge City Council Cambridgeshire County Council Cambridgeshire Horizons East Cambridgeshire District Council Environment Agency Fenland District Council Huntingdonshire District Council Natural England South Cambridgeshire District Council The Wildlife Trust Consultants: LDA Design Page 2 of 176 Contents 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................11 2 Background