Interview with Akira Kurosawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Samurai Rip Offs

Seven Samurai rip offs- 13th Warrior The Magnificent Seven Ronin Dirty Dozen Saving Private Ryan The Wild Bunch Conan the Barbarian (1982) Battle Beyond the Stars Last Man Standing /Yojimbo The Bodyguard, Kevin Costner watches a screening of Kurosawa's film and later does some samurai-ish turns with a sword (Yojimbo, loosely translated, is Japanese for "bodyguard"). THE FILMS of Akira Kurosawa have always been a point at which Eastern and Western currents crossed. His Throne of Blood (1957) retold Macbeth, and Ran (1985) resembled King Lear. And Kurosawa hasn't borrowed only from high art. His thriller High and Low (1963) was an adaptation of 87th-precinct creator Ed McBain's novel King's Ransom. Western filmmakers have returned the compliment, if it can be considered such. Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai (1954) was turned into the 1960 Western hit The Magnificent Seven, and Rashomon (1950) was clumsily translated into Martin Ritt's The Outrage (1964). Although Kurosawa's borrowings from Shakespeare and McBain were acknowledged, The Magnificent Seven and The Outrage were made without the master's approval or even his knowledge. Kurosawa apparently reached his limit with A Fistful of Dollars and sued in an Italian court. Leone, incredibly, denied the connection between his film and Yojimbo, even though numerous critics have pointed out the similarities not only in plot but in shot selection and camera angles. After the suit dragged on for years, Kurosawa finally received a portion of the profits from A Fistful of Dollars and the copyrights to Yojimbo, while United Artists, Leone's distributor, retained copyrights to A Fistful of Dollars. -

Shakespeare Bulletin Final Article Project Muse 629790.Pdf

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The Auteur Affect: "Forces of Encounter" between Shakespeare and Kurosawa in The Bad Sleep Well AUTHORS Gee, FC JOURNAL Shakespeare Bulletin: a journal of performance, criticism, and scholarship DEPOSITED IN ORE 24 November 2016 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/24579 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 7KH$XWHXU$IIHFW¶)RUFHVRI(QFRXQWHU·EHWZHHQ6KDNHVSHDUHDQG.XURVDZDLQ 7KH%DG6OHHS:HOO )HOLFLW\*HH 6KDNHVSHDUH%XOOHWLQ9ROXPH1XPEHU)DOOSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2, KWWSVGRLRUJVKE )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Exeter (23 Nov 2016 16:34 GMT) The Auteur Affect: ‘Forces of Encounter’ between Shakespeare and Kurosawa in The Bad Sleep Well FELICITY GEE University of Exeter In “Revenge of the Author” (1999), Colin MacCabe attempts to “bring into alignment two major and contradictory areas” that he finds difficult to resolve within the field of 1970s film studies. The first of these is the seismic shift brought about by reading Roland Barthes’s “The Death of the Author” (1967), and the second his own participation in the making of feature films. The former dispatches with the “origin” (author) of the text in favor of the destination (reader/audience), while the experience of being an active crewmember on a film set reveals the steer of an author (MacCabe 30). As MacCabe notes, in the 1970s the discipline of film studies was largely defined by the seeming impasse posited via theories of authorship in Cahiers du cinéma and dissected in concurrent works of poststructuralism: “For Barthes, the author is the figure used to obscure the specificity of the textual. -

Confucian Philosophy in the Films of Akira Kurosawa Through the Documentary Film Medium

Wu, Li-Hsueh Truth and Beauty: Confucian Philosophy in the Films of Akira Kurosawa Through the Documentary Film Medium Doctor of Design 2008 Swinburne Abstract This doctoral research consists of two 90 minute DVD documentaries and a complementary text about the Japanese film director, Akira Kurosawa, a major figure in 20th century cinema. It focuses on how the Confucian cultural heritage has informed many aspects of his approach to filmmaking, especially his manifestation of philosophical and aesthetic concepts. To bridge the gap in the existing critiques of Kurosawa’s films, the research incorporates critical analysis of interviews with twelve filmmakers and scholars in philosophy, history, arts, drama and film. The interviews discuss the aesthetic elements from traditional arts and theatre, and address a failure in the literature to draw from the deep meaning of the Confucian cultural heritage. The first documentary, An Exploration of Truth in the Films of Akira Kurosawa, has three sections: The Way of Self- Cultivation, The Way of Cultivating Tao and The Way of Cultivating Buddhism. It explores how the films of Kurosawa manifested the Confucian philosophy via inner self-cultivation, which displayed his humanist values. It also examines the ‘outer enlightenment pattern’ in Kurosawa’s films which effects profound dramatic tension. The interrelationship between Confucianism, Shinto and Buddhism in different periods of Kurosawa’s films is explored, focusing on issues of historical background, cultural heritage and philosophy and film narrative elements. The second documentary, The Origin and Renovation of Traditional Arts and I Theatre in the Films of Akira Kurosawa, has three sections: Structure and Mise-En-Scene from Noh and Kabuki, Representation and Symbolism from Noh Masks and Chinese Painting and Color and Mise-En-Scene from The ‘Five Elements’ Theory and Japanese Prints. -

Akira Kurosawa: a Centennial Celebration

JANUS FILMS PRESENTS AKIRA KUROSAWA: A CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION JANUS FILMS Sarah Finklea Ph: 212-756-8715 [email protected] http://www.janusfilms.com/kurosawa AKIRA KUROSAWA: A CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION SERIES SYNOPSIS Arguably the most celebrated Japanese filmmaker of all time, Akira Kurosawa had a career that spanned from the Second World War to the early nineties and that stands as a monument of artistic, entertainment, and personal achievement. His best-known films remain his samurai epics Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, but his intimate dramas, such as Ikiru and High and Low, are just as searing. The first serious phase of Kurosawa’s career came during the postwar era, with Drunken Angel and Stray Dog, gritty dramas about people on the margins of society that featured the first notable appearances by Toshiro Mifune, the director’s longtime leading man. Kurosawa would subsequently gain international fame with Rashomon, a breakthrough in nonlinear narrative and sumptuous visuals. Following a personal breakdown in the late sixties, Kurosawa rebounded by expanding his dark brand of humanism into new stylistic territory, beginning with Dodes’ka-den, his first film in color. Janus Films is proud to honor the 100th anniversary of his birth with a nationwide tour of fifteen key films, including new 35mm prints of Stray Dog, Rashomon, and the previously unavailable Dodes’ka- den. AKIRA KUROSAWA: A CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION DRUNKEN ANGEL In this powerful early noir, Toshiro Mifune bursts onto the screen as a volatile, tubercular criminal who strikes up an unlikely relationship with Takashi Shimura’s jaded physician. Set in and around the muddy swamps and back alleys of postwar Tokyo, Drunken Angel is an evocative, moody snapshot of a treacherous time and place, featuring one of the director’s most memorably violent climaxes. -

Akira Kurosawa: RASHOMON (1950, 88 Min) Online Versions of the Goldenrod Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Links

October 2, 2018 (XXXVII:6) Akira Kurosawa: RASHOMON (1950, 88 min) Online versions of The Goldenrod Handouts have color images & hot links: http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html DIRECTED BY Akira Kurosawa WRITTEN BY Ryûnosuke Akutagawa (stories), Akira Kurosawa (screenplay) and Shinobu Hashimoto (screenplay) PRODUCED BY Minoru Jingo, Masaichi Nagata (executive producer) MUSIC BY Fumio Hayasaka CINEMATOGRAPHY Kazuo Miyagawa EDITING Akira Kurosawa PRODUCTION DESIGN Takashi Matsuyama SET DECORATION H. Motsumoto SOUND Tsuchitarô Hayashi, Iwao Ôtani VISUAL EFFECTS Aurelio x. Vera Jr. (restoration artist, restored version), Rejyna Douglass-Whitman (restoration supervisor) entertained worldwide audiences and influenced filmmakers Academy Awards, USA 1952 throughout the world.” Winner Honorary Award: Japan He directed 33 films, some of which are: Uma (1941, some Voted by the Board of Governors as the scenes, uncredited), Sanshiro Sugata (1943), and The Most most outstanding foreign language film Beautiful (1944); Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail in 1945; Those Who Make Tomorrow CAST and No Regrets for Our Youth in 1946; One Wonderful Sunday Toshirô Mifune...Tajômaru (1947) and Drunken Angel (1948); The Quiet Duel and Stray Machiko Kyô...Masako Kanazawa Dog in 1949; Scandal and Rashomon in 1950; The Idiot (1951), Masayuki Mori...Takehiro Kanazawa Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai (1954); Throne of Blood and Takashi Shimura...Woodcutter The Lower Depths in 1957; The Hidden Fortress (1958), The Minoru Chiaki...Priest Bad Sleep Well (1960), Yojimbo (1961), Sanjuro (1962), High Kichijirô Ueda ...Commoner and Low (1963), and Red Beard (1965); Song of the Horse (TV Noriko Honma...Medium Movie documentary) and Dodes'ka-den in 1970; Dersu Uzala Daisuke Katô...Policeman (1975), Dreams (1990), Rhapsody in August (1991), and Maadadayo (1993). -

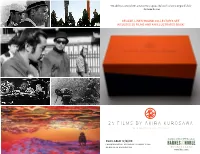

2 5 F I L M S B Y a K I R a K U R O S

“His ability to transform a vision into a powerful work of art is unparalleled.” —George Lucas DelUXe, linen-boUnD ColleCToR’S SeT inClUDeS 25 FilMS AnD An illustrateD book! 25 Films By AkirA kurosAwA the criterioN collectioN • JaNus Films AvAilAble 12/8/09 preorder NoW at aNy BarNes & NoBle store or oNliNe at WWW.BN.com The creator of such timeless masterpieces as Rashomon, Ikiru, Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, and High and Low, Akira Kurosawa is one of the most influential and beloved filmmakers who has ever lived—and for many the greatest artist the medium has ever known. Now, on the centenary of his birth, the Criterion Collection and Janus Films are pleased to present this box set celebrating his astonishing career. Featuring twenty-five of the films Kurosawa made over the course of his fifty years in movies—from samurai epics to postwar noirs to Shakespeare adaptations—AK 100 is the most complete set of his works ever released in this country. 25-DiSC ColleCToR’S SeT FeATUReS The bAD Sleep Well (1960) ikiRU (1952) The Men Who TReAD on The RashoMon (1950) Scandal (1950) DoDeS’kA-Den (1970) i live in FeAR (1955) TigeR’S TAil (1945)* ReD beARD (1965) Seven SAMURAi (1954) DRUnken Angel (1948) kAgeMUShA (1980) The Most beautiFUl (1944)* SAnjURo (1962) STRAy Dog (1949) The hiDDen FortreSS (1958) The loWeR DepThS (1957) no RegReTS FoR oUR SAnShiRo SUgata (1943)* ThRone oF blooD (1957) high AnD loW (1963) Madadayo (1993) yoUTh (1946) SAnShiRo SUgata, yojiMbo (1961) The iDioT (1951) one WonDeRFUl SUnday (1947) Part TWo (1945)* *First time on DVD in the U.S. -

Akira Kurosawa Director, Screenwriter

Akira Kurosawa Director, Screenwriter Birth Mar 24, 1910 (Tokyo, Japan) Death Sep 6, 1998 (Tokyo, Japan Genres Drama, The most well-known of all Japanese directors, the great irony about Akira Kurosawa's career is that he's been far more popular outside of Japan than in Japan. The son of an army officer, Kurosawa studied art before gravitating to film as a means of supporting himself. He served seven years as an assistant to director Kajiro Yamamoto before he began his own directorial career with Sanshiro Sugata (1943), a film about the 19th century struggle for supremacy between adherents of judo and jujitsu that so impressed the military government, he was prevailed upon to make a sequel (Sanshiro Sugata Part Two). Following the end of World War II, Kurosawa's career gathered speed with a series of films that cut across all genres, from crime thrillers to period dramas. Among the latter, his Rashomon (1951) became the first postwar Japanese film to find wide favor with Western audiences, and simultaneously introduced leading man Toshiro Mifune to Western viewers. It was Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai (1954), however, that made the largest impact of any of his movies outside of Japan. Although heavily cut for its original release, this three-hour-plus medieval action drama, shot with painstaking attention to both dramatic and period detail, became one of the most popular Japanese films of all time in the West, and every subsequent Kurosawa film has been released in the U.S. in some form, even if many — most notably The Hidden Fortress (1958) — were cut down in length. -

タリforces of Encounter¬タル Between Shakespeare and Kurosawa in The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Research Exeter 7KH$XWHXU$IIHFW¶)RUFHVRI(QFRXQWHU·EHWZHHQ6KDNHVSHDUHDQG.XURVDZDLQ 7KH%DG6OHHS:HOO )HOLFLW\*HH 6KDNHVSHDUH%XOOHWLQ9ROXPH1XPEHU)DOOSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2, KWWSVGRLRUJVKE )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Exeter (23 Nov 2016 16:34 GMT) The Auteur Affect: ‘Forces of Encounter’ between Shakespeare and Kurosawa in The Bad Sleep Well FELICITY GEE University of Exeter In “Revenge of the Author” (1999), Colin MacCabe attempts to “bring into alignment two major and contradictory areas” that he finds difficult to resolve within the field of 1970s film studies. The first of these is the seismic shift brought about by reading Roland Barthes’s “The Death of the Author” (1967), and the second his own participation in the making of feature films. The former dispatches with the “origin” (author) of the text in favor of the destination (reader/audience), while the experience of being an active crewmember on a film set reveals the steer of an author (MacCabe 30). As MacCabe notes, in the 1970s the discipline of film studies was largely defined by the seeming impasse posited via theories of authorship in Cahiers du cinéma and dissected in concurrent works of poststructuralism: “For Barthes, the author is the figure used to obscure the specificity of the textual. ForCahiers , the author, while sharing the Romantic features of creativity, inferiority, etc., -

Hayasaka Fumio, Ronin Composer

HAYASAKA FUMIO, RONIN COMPOSER: ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY OF FIVE FILM SCORES by MICHAEL WILLIAM HARRIS B.M., Truman State University, 2004 M.A., University of Missouri–Kansas City, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Music 2013 This thesis entitled: Hayasaka Fumio, Ronin Composer: Analysis and Commentary of Five Film Scores written by Michael William Harris has been approved for the College of Music Dr. Thomas L. Riis Dr. Jennifer L. Peterson Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Harris, Michael William (Ph.D., Musicology, College of Music) Hayasaka Fumio, Ronin Composer: Analysis and Commentary of Five Film Scores Thesis directed by Professor Thomas L. Riis Hayasaka Fumio (1914–55) worked with some of Japan’s most famous film directors during his sixteen year career while winning numerous accolades for both his film and concert music, though his name and work are little known outside of his native country. Self-taught, he brought new ideas to Japanese music and was a key figure in the developments made in the post- war era and a major influence on subsequent composers. Hayasaka’s style blended traditional Asian musical elements—primarily Japanese, though he also studied Indonesian and Chinese music—with the Western orchestra, creating what he called a Pan-Asian style. -

Prologue 1 Setting the Scene

Notes Prologue 1. For Japanese names I have generally used the order used in Japan: surname followed by first name. However, for personages that are well known outside Japan, I have referred to them as would film critics, theorists, and audiences: first name followed by surname. 2. In fact North American cultural anthropologists have tried to do away with the “culture concept,” thereby essentially undermining their own discipline— much to the amusement of sociologists—and certainly contravening the empirical trend found in most societies, which firmly insist on the existence of their own unique cultures. 3. Although I wonder if the financial is really ignored. Recently my own chil- dren startled me by announcing that they could not believe that a certain famous director had helped produce what they thought was a terrible film. They expected him to have a better sense of where to put his money. 4. Bruner, of course, relies on the work of many others—Barthes, Ricoeur, Chomsky, Kermode—to make his points. 1 Setting the Scene 1. In contrast, the science fiction writer William Gibson (2001) seems well aware of such conceptual loci and even situates them on actual bridges—the meta- phor made real—in his novels. Building on Augé’s (1995) terms, non-places become the birthplaces of innovation. 2. Silent nonnarrative films were shown throughout the end of the nineteenth cen- tury. For example, Japan saw its first film in 1898 (cf. Anderson and Richie 1982). The first narrative film was The Great Train Robbery (1903) directed and photographed by Edwin S. -

AFI Preview-Augsept03

THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE August 8—September 17, 2003 ★ AFITO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS PREVIEWVOLUME 1 • ISSUE 4 Celebrating the Director Akira Kurosawa The Legacy of Sergio Leone Gregory Peck French Superstar Alain Delon DC Labor Filmfest More of AFI’s 100 Best Also: A WOMAN IS A WOMAN DRACULA: PAGES FROM A VIRGIN’S DIARY THE SAME RIVER TWICE BARAKA THE ANIMATION SHOW FEATURED FILMS KUROSAWA IN COLOR Akira Kurosawa came late to color. And it coincided with his great changes in simplification of style and darkening of theme—still being debated. But it obvi- ously unleashed the painter he had trained to be in his youth, as he selected from the richest of palettes the most evocative of shades, regardless of realism—in his most naturalist work, DERSU UZALA, he even makes red the most bone-chilling of hues. Enjoy—almost complete (DODESKADEN is presently unavailable; perhaps a new print will be released in 2004)— the last, still controversial—but still power-packed—period from the work of the most Shakespearian of filmmakers. THE SEA IS WATCHING Michael Jeck, AFI Silver programmer and the voice on the commentary tracks The Washington Area Premiere of of the SEVEN SAMURAI and THRONE OF BLOOD DVDs, will discuss and illustrate with clips the controversial changes of style and theme in Kurosawa’s late, color period before the Friday, August 8 screening of RAN. There will be a THE SEA IS WATCHING brief intermission before the screening. [Umi Wa Miteita] Fri, Aug 8 - Thu, Aug 14, 6:40 & 8:55; RAN[Chaos] weekend matinees 1:50 and 4:10 Fri, Aug 8, 7:30; Sat, Aug 9, 1:00; Akira Kurosawa’s last screenplay, in what would have been his first Sat, Aug 16, 9:00; Sun, Aug 17, 1:00; Mon, Aug 18, 7:30; film focusing exclusively on women’s problems. -

Research Material Cinema Japan 2020 a Quick History of Japanese Cinema

RESEARCH MATERIAL CINEMA JAPAN 2020 A QUICK HISTORY OF JAPANESE CINEMA 1890’s- 1920’s: the silent era Matsunosuke Onoe Cinema arrived in Japan at the end of 19th century, but the Japanese had already a rich tradition of moving pictures with pre-cinematic devices such as Utushi-e, a type of magic lantern that become popular in Japan in the 19th century. Early 20th century, most of Japanese cinema theatres employed Benshi and live musicians. The Benshi are Japanese storytellers performing live narration for silent films. The 1923 earthquake, the bombing of Tokyo during WWII and Japan’s natural humidity partially destroyed the film stock of this period. There are no many surviving films. Films • Geisha No Teodori, 1899: first film produced in Japan. Only some fragments of the film remain intact. Important names Matsunosuke Onoe, a Kabuki actor who appeared in over 1000 films between 1909 and 1926, he’s considered the first star of Japanese cinema. Shozo Makino, director and film pioneer, he popularized the Jidaigeki (period pieces) @FilmHubMidlands [email protected] The 1930s Heihachirō Ōkawa and Sachiko Chiba in Wife! Be Like A Rose, directed by Mikio Naruse, 1935 Talkie films arrived in Japan in the early 30s, but silent films were still being produced, until the Benshi’s strike (1932). In the early 30’s, Kenji Mizoguchi and a group of progressive filmmakers produced left-leaning “social tendency films”. But Japan’s increasingly militarist government instituted a crackdown on the political content of films, which were expected to conform a national policy of pro-family and pro- military values.