Rakhine Humanitarian Response February 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Acknowledgments

FACTORS AFFECTING COMMERCIALIZATION OF THE RURAL LIVESTOCK SECTOR Acknowledgments Thisresearch study was led by U Kyaw Khine & Associates with the assistance of the field survey team of the FSWG members organizations. The research team would like to express sincere thanks to Dr Ohnmar Khaing (FSWG Coordinator), Dr. Min Ko Ko Maung, (Deputy Coordinator), and Mr. Thijs Wissink (Programme Advisor) for their kind and effective support for the research. The team is especially grateful to Daw Yi Yi Cho (M&E Officer) for providing logistical and technical support along with study design, data collection, analysis, and report writing. Finally, this research would not have been possible without the valuable participation and knowledge imparted by all the respondents from the villages of Pauktaw and Taungup Townships and focus group discussion (FGD) participants. The research team would like to acknowledge the experts and professors from respective institutions concerned with livestock who willingly agreed to take part in the FGDs. We are greatly indebted to them. 1 FACTORS AFFECTING COMMERCIALIZATION OF THE RURAL LIVESTOCK SECTOR Ensure adequate financial and human resources to village volunteers for veterinary extension services to cover all rural areas Upgrade local pig breeds with improved variety for better genetic performance in rural livestock production Attract private sector investment to finance all livestock support infrastructure, such as cold chain, cold storage, animal feed mills, veterinary drugs, and meat and -

Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Report Census Report Volume 3 – K For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014, and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results, both Union and each of the State and Region reports, will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township Levels, and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. The technical support and our strong desire to follow international standards affirmed our commitment to strict adherence to the guidelines and recommendations, which form part of international best practices for census taking. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Disaster Preparedness and Health Services Organization in Events Of

NationalNational HealthHealth PerspectivesPerspectives inin thethe TsunamiTsunami CrisisCrisis (Myanmar)(Myanmar) S U B D U C T I O N Z O N E 26-12-2004 &ufaeYwGif vIyf½Sm;cJhaom ajrivsifA[dkcsufESifh tiftm;jy ajryHk jrefrmE dkifiH 20 N tdEd,E dkifiH &efuke fNrdKU 15 N Richter MST udkudk xdkif;E 12 scale (hr) ;uRef; dkifiH µ 8.5 07:32 1 5.9 08:18 10 N 2 5.8 08:45 11 uyÜvD 3 6.0 08:52 yifv,fjyif 4 5.8 09:04 5 5.8 09:06 6 6.0 09:21 7 5.9 09:29 5 N 8 6.1 09:38 9 7.3 10:51 µ 10 5.7 12:51 11 5.7 13:37 12 5.8 14:08 b*Fvm;yifv,fatm tif'dkeD;½S 0 f m;EdkifiH 5 S MyanmarMyanmar The organogram for Disaster Preparedness and Response National Disaster Preparedness, Relief and Resettlement Committee State / Division Disaster Preparedness, Relief and Resettlement Committee State/Division Disaster State/Division Disaster Relief and Preparedness Resettlement sub committee Subcommittee Working Committee on (a) Transport (b) Security (c) Information State / Division Disaster Preparedness, Relief and Resettlement Committee Chairman Deputy Commander or Chairman of State / Division Peace and Development Council Secretary S/D Director Fire Services Department Duties and Responsibilities – To draw state / divisional plan for disaster preparedness and relief and draw distinct / township plans in line with State/Division plan. Formulation of disaster preparedness plan and preventive measures. – To form distinct / township disaster preparedness, relief and resettlement committee and subcommittees and also form committee at ward and village tract level. -

Demographic Characteristic S and Road Network on the Spread of Coronavirus Pandemic in Rakhine State

THE IMPACT OF DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS AND ROAD NETWORK ON THE SPREAD OF CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC IN RAKHINE STATE: USING GEOSPATIAL TECHNIQUES Mu Mu Than (1), Khin Mar Yee (2), Tin Tin Mya (3), Thida Win (4) 1 Sittway University, Rakhine State, Myanmar 2 Myeik University, Tanintharyi Region, Myanmar 3 Pathein University, Ayeyarwady Region, Myanmar 4 East Yangon University, Yangon Region, Myanmar [email protected] KEY WORDS: connectivity, demographic characteristics, confirmed cases, factor 1. INTRODUCTION analysis, interaction Rakhine State has 5 districts in which 17 ABSTRACT: Demographic characteristics townships and 3sub-townships are included. give communities information for the past, Percentage of urban population is 17%. It has present and future plan and services. more rural nature. Total number of population Demographic data and connectivity of road in Rakhine State is 3,188,807 (2014 Census). It has an area of 36,778.1 Km2. Population network impact how far people travel and 2 what they do. The spread of COVID-19 cases density is 86.7 per km . It faces the Bay of in the state deals with these data. Bengal on the west, Bangladesh in the northwest and the India in the north. In the In the 31st August 2020 COVID-19 east it is bordered by state and regions of the confirmed cases across the state had risen to country (Figure 1). Waterway is important to 350 cases. This is more than that of Yangon the transportation of people and goods in the Region. The researchers are interested in the middle and northern part of the states to reasons for that. -

Tropical Cyclone Mahasen Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2013 May 15, 2013

TROPICAL CYCLONE MAHASEN FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2013 MAY 15, 2013 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE Tropical Cyclone Mahasen is due to make landfall in Bangladesh, near the Burma border, on May 16 with winds 8.2 million of up to 63 miles per hour People in Bangladesh, The storm has already caused 7 deaths Burma, and India who may and displaced 115,000 people in Sri be significantly affected by Lanka as it tracked near the country Tropical Cyclone Mahasen Humanitarian preparedness activities U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – are underway in Bangladesh and May 14, 2013 Burma, including pre-positioning of relief supplies and evacuation of populations residing in areas at high 68,000 risk of severe storm impact IDPs in Burma’s Rakhine USAID/OFDA staff have arrived on State identified as the ground in Bangladesh and Burma particularly vulnerable to and stand ready to help coordinate a Tropical Cyclone Mahasen’s trajectory as of 11:00 a.m. on May 15, the storm due to their USG response to cyclone-related 2013. (Source: U.S. Joint Typhoon Warning Center) inadequate shelter humanitarian needs if required OCHA – April 2013 KEY DEVELOPMENTS 140,000 As of 11:00 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time on May 15, the center of Tropical Cyclone Estimated number of IDPs Mahasen was located some 283 miles south of Kolkata, India. The U.S. Joint Typhoon in Burma’s Rakhine State Warning Center anticipates that the storm will continue tracking northeastward and make OCHA – April 2013 landfall south of Chittagong city, southeast Bangladesh, on May 16. -

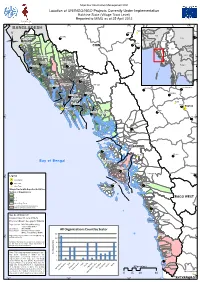

Mimu861v01 120611 3W Rakhine State VT A3.Mxd

Myanmar Information Management Unit Location of UN/INGO/NGO Projects Currently Under Implementation Rakhine State (Village Tract Level) Reported to MIMU as of 25 April 2012 92°0'E 93°0'E 94°0'E 95°0'E BANGLADESH Pauk Kyaukhtu Mindat (! Bhutan Nepal Pakokku India Paletwa Kachin Maungdaw China Bangladesh Sagaing Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U (! CHIN Saw Bagan Vietnam (! Ü Chin Shan (! Mandalay Magway Kayah Laos Buthidaung Rakhine 21°0'N Bago 21°0'N Yangon Kyauktaw Chauk Buthidaung Ayeyarwady Kayin Seikphyu Kyauktaw Thailand Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mon Mrauk-U Cambodia Rathedaung MAGWAY Tanintharyi Mrauk-U Salin Ponnagyun Rathedaung Minbya Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Pauktaw Saku (! Sittwe Pauktaw Minbu Magway .! Sittwe .! Ngape Myebon Myebon Minhla 20°0'N Ann 20°0'N Ann RAKHINE Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon (! Bay of Bengal Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Kamma Legend 19°0'N 19°0'N .! State Capital Main Town Munaung Toungup (! Other Town Village Tracts with Reported Activities Munaung Number of Organizations 1 2 - 3 BAGO WEST 4 - 6 Other Village Tracts Township (Orgainzations presence Thandwe without specifying Village Tract) Map ID: MIMU861v01 Creation Date: 11 June 2012.A3 Thandwe Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Data Sources : Who/What/Where data collected by MIMU Boundaries : WFP/MIMU Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs All Organizations Count by Sector (GAD), translated by MIMU 12 Kyeintali Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] (! www.themimu.info 18°0'N 10 18°0'N Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used 8 on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

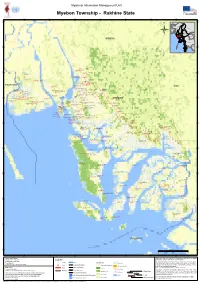

Myebon Township - Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myebon Township - Rakhine State 93°15'E 93°20'E 93°25'E 93°30'E 93°35'E 93°40'E 93°45'E 20°20'N 20°20'N BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Ü VIETNAM LAOS MINBYA THAILAND CAMBODIA 20°15'N 20°15'N Kyar Inn Taung (197349) (Shauk Chon) Shauk Chon (197347) (Shauk Chon) Kyant Hin Khar (197348) 20°10'N 20°10'N Thin Ga Net (197358) (Shauk Chon) (Thin Ga Net) Kyauk Nga Nwar (197286) Ka Paing Chaung (197335) (Kyauk Nga Nwar) (Pin Kat Chaung) Ah Lel Kyun (197257) (Ah Lel Kyun) Ah Twin Nga Khu Chaung (197258) (Ah Twin Nga Khu Chaung) Chaung Gyi (197336) (Pin Kat Chaung) Pin Kat Taung Maw (197332) Kant Kaw Chaung (197337) (Pin Kat Taung Maw) (Pin Kat Chaung) Kat Taung Swea (197334) Pin Kat Taung Auk (197333) (Pin Kat Taung Maw) PAUKTAW Wet Gaung (197280) (Pin Kat Taung Maw) (Gaung Hpyu) ANN Thar Yar Wa Di (197273) Bar Wai (197338) (Daing Bon) (Pin Kat Chaung) War Khoke Chaung (197370) Mi Kyaung Tet (197368) Myauk Kyein Paik Seik (217990) Ta Laing Pyin (197269) Kyauk Tan (197330) (Yet Chaung) (Yet Chaung) (Myauk Kyein) (Chon Chaung) Myauk Kyein (197303) (Pe Kauk) Pe Kauk (197329) Daing Bon (197271) (Pe Kauk) (Daing Bon) (Myauk Kyein) Dagon (197279) Chaung Shey (197340) (Gaung Hpyu) (Pin Kat Chaung) Tha Pyay Taw (197369) Ta Dar U (197304) (Yet Chaung) Lay Taung (197367) (Myauk Kyein) Kyauk Hpya Lar (197282) Nga Sin Pone (197339) (Yet Chaung) Kan Thar (197278) (Kyauk Hpya Lar) (Pin Kat Chaung) Yet Chaung (197366) Nga Man Ye Gyi (197306) (Gaung Hpyu) Pin Khar (197266) Gaung Hpyu (197277) (Yet Chaung) (Nga Man Ye Gyi) Pyin -

MYANMAR, RAKHINE STATE: COVID-19 Situation Report No

MYANMAR, RAKHINE STATE: COVID-19 Situation Report No. 08 1 September 2020 This report, which focuses on the recent surge in COVID-19 cases in Rakhine, is produced by OCHA Myanmar covering the period of 10 to 31 August, in collaboration with Inter-Cluster Coordination Group and wider humanitarian partners. The next report will be issued on or around 18 September. HIGHLIGHTS • A total of 393 locally transmitted cases have been reported across Rakhine between 16 August and 1 September, bringing to 409 the number of cases in 16 townships since 18 May. Across the country, 887 cases, six fatalities and 354 recoveries have been reported. • The recent surge in local transmission includes COVID-19 positive cases among the personnel of the United Nations agencies and international non-governmental organizations (INGO). • No cases have been reported in camps or sites for internally displaced people (IDPs) as of 31 August, while displaced persons who had been in contact with COVID-19 confirmed cases were placed in quarantine and tested. • Sittwe General Hospital, where most COVID-19 confirmed cases are being treated, remains the primary treatment facility for Rakhine. Efforts to increase treatment capacities continue. • The Rakhine State Government has introduced various COVID-19 measures since 16 August, including a state-wide “stay-at-home” order and other measures aimed at preventing the local transmission. • Humanitarian actors are assessing the impact of the recently introduced COVID-19 measures on operations, including COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. SITUATION OVERVIEW 409 16 393 887 157K Cases in Rakhine Townships Locally transmitted Cases countrywide Total tests conducted countrywide SURGE IN LOCAL TRANSMISSION: Since 16 August, when the Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) confirmed a new COVID-19 case in Sittwe - the first case of local transmission reported in almost a month country-wide - the number of locally transmitted cases has continued to increase in Rakhine State.