Living with an Acquired Brain Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rts Announces Winners for the Programme Awards 2009

P R E S S R E L E A S E Tuesday16 March 2010 RTS ANNOUNCES WINNERS FOR THE PROGRAMME AWARDS 2009 The Royal Television Society (RTS), Britain’s leading forum for television and related media, has announced the winners for the RTS Programme Awards 2009. The ceremony, held at Grosvenor House on Tuesday 16 March, was hosted by actor, comedian and radio presenter Rob Brydon and the awards were presented by RTS Chair, Wayne Garvie. The RTS Programme Awards celebrate all genres of television programming, from history to soaps, children's fiction to comedy performance. Covering both national and regional output, as well honouring the programmes themselves, they aim to recognise the work of exceptional actors, presenters, writers and production teams. The Winners: Scripted Comedy The Thick of It BBC Productions for BBC Two “An acerbic, intelligent and sweeping comedy which attained new heights. Faultless ensemble acting, meticulous writing and intricately contrived comedy climaxes combined to make this a series we didn‟t want to end.” Nominees Miranda BBC Productions for BBC Two The Inbetweeners A Bwark Production for E4 Entertainment Newswipe with Charlie Brooker Zeppotron for BBC Four “Right on the money... Refreshingly polemical and with real authenticity.” Nominees Britain's Got Talent A talkbackTHAMES and SYCO TV Production for ITV1 The X Factor A talkbackTHAMES and SYCO TV Production for ITV1 2-6 Northburgh Street, London EC1V 0AY +44 (0) 20 7490 4050 www.franklinrae.com Daytime and Early Peak Programme Come Dine With Me ITV Studios for -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 31 Sydney Program Guide Sun Dec 17, 2017 06:00 FLIPPING THE HEARTLAND Repeat WS G Big House, Big Problems In order to keep the purchase price down on a large property in Broken Arrow, OK, Dan and Melinda agree to take it sight-unseen. But as they begin their renovation plans, they run into severe water damage and a crumbling foundation. 06:30 FLIPPING THE HEARTLAND Repeat WS G Retro Rehab Dan and Melinda purchase a house in Highland Park, OK, with a dated design and an odd floor plan that quickly becomes a money pit. 07:00 COLIN & JUSTIN'S HOME HEIST Repeat WS PG Baby In The Laundry Colin and Justin try to renovate Ian and Ashley's home. Cons.Advice: Sexual References, Some Coarse Language 08:00 EXTREME HOMES Repeat WS G Upside Down, Wave, Spaceship This amazing assortment of homes from all over the world includes a house hidden behind a wooden grille in Italy, a wave-form residence in California and an Austrian residence that's rusting beautifully. 09:00 GETAWAY Captioned Repeat WS PG This week on Getaway Tim Blackwell takes a tour through Hawaii's answer to Hollywood, the famous Kualoa Ranch. Catriona is in Bali checking out some wonderful places to stay and David Reyne is sailing around Tasmania's stunning Freycinet Peninsula. 09:30 POSTCARDS SUMMER Captioned WS PG Bec visits immaculate South Hampton mansion in Red Hill and enjoys the enchanting Cruden Farm, Alex checks out fellow teammate- Dylan Grimes' new Mt Macedon winery and Brodie finds all the thrills at Adventure Park. -

Come Dine with Me Is Europe's Top Format

Come Dine with Me is Europe’s top format Come Dine with Me (4,126 hours) was the most screened TV format in Europe in 2011, according to a new report that covers 50 major formats across 16 countries. The TV Formats in Europe report calculates that the hourly total of Endemol’s Big Brother has fallen considerably since 2009, with Who Wants to Be a Millionaire also declining. Jonathan Bailey, co-author and Managing Director at Essential Television Statistics, added: “Money Drop was screened for 615 hours and The Voice for 312 hours in 2011 – impressive considering that both shows only started in 2010. Both are expected to grow sharply in 2012.” Top five titles by value created in 2011 ($ million) Channel Distributor $ mil. Come Dine with Me ITV Studios 217.4 Money Drop Endemol 171.2 Who wants to be a Millionaire? Sony 165.2 Dancing with the Stars BBC Worldwide 140.1 Got Talent FremantleMedia 121.5 Source: Essential Television Statistics, Madigan Cluff, Digital TV Research Relative newcomer Money Drop has already become the second title by value created across Europe. More established titles such as Big Brother, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, Wheel of Fortune and Deal or No Deal saw considerable falls in value for calendar 2011 compared to 2009 and 2010. Total format hours (for the 50 titles covered) in Europe was 16,856 in 2011, comparable with 2009 and 2010. The UK was the leading country, but its 2011 total was considerably lower than in 2010. Five began transmitting Big Brother in 2011, transmitting many fewer hours than Channel 4/E4, the previous broadcasters. -

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 220 17 December 2012 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 220 17 December 2012 Contents Introduction 4 Standards cases In Breach Line of Duty BBC 2, 17 July 2012, 21:00 and 24 July 2012, 21:00 5 Note to Broadcasters The involvement of people under eighteen in programmes 16 In Breach Paigham-e-Mustafa Noor TV, 3 May 2012, 11:00 18 Rock All Stars Scuzz TV, 19 August 2012, 20:40 32 Islam Channel News The Islam Channel, 8 June 2012, 21:10 43 Good Cop (Trailer) BBC1 HD, 6 August 2012, 18:40 51 Not in Breach The X Factor ITV1, 9 September 2012, 20:00 ITV2, 10 September 2012, 01:05, 10 September 2012, 20:00 and 11 September 2012, 00:15 55 Broadcast Licence Condition cases In Breach Breach of licence conditions Voice of Africa Radio 60 In Breach/Resolved Breach of licence conditions Erewash Sound, Felixstowe Radio, The Super Station Orkney, Seaside FM, Ambur Radio, Phoenix FM 62 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 220 17 December 2012 Fairness and Privacy cases Upheld Complaint by Complaint by the Central Electoral Commission of Latvia Russian language referendum item, REN TV Baltic & Mir Baltic, November 2011, various dates and times 66 Complaint by Dr Usama Hasan Islam Channel News, The Islam Channel, 8 June 2012 70 Not Upheld Complaint by Dr Usama Hasan Politics and Media, The Islam Channel, 11 June 2012 77 Other Programmes Not in Breach 89 Complaints Assessed, Not Investigated 90 Investigations List 100 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 220 17 December 2012 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1, Ofcom must include these standards in a code or codes. -

TV Formats in Europe

TV Formats in Europe Given the prolonged advertising recession and the fact that several major titles have peaked, the TV formats market in Europe is showing remarkable resilience. The value created by the top 100 formats was $2,931 million in 2013 for 84 European channels across the 16 territories and 21 distributors, according to the TV Formats in Europe report. The 2013 figure was 3.3% down on the 2012 total, but up on 2011. The number of hours broadcast reached 28,386 in 2013, nearly the same as 2012. The UK is the TV formats leader in Europe – just ahead of France. The value created by formats for UK broadcasters was $600 million in 2013, down from $677 million in 2012. France recorded $599 million in 2013, up from $547 million in 2012. The UK, France, Germany and Italy accounted for 72% of Europe’s total value created in 2013. The top 10 broadcasters accounted for two-thirds of the total value created in Europe for 2013 – which means that the remaining third was shared by 74 channels. France’s TF1 ($332 million) led the pack again, followed by Italy’s Rai 1 and the UK’s BBC1. The total number of hours broadcast in Europe for the 100 formats was 28,386 in 2013; very close to 2012. The UK was the leader again, despite its 2013 total (3,935) being considerably lower than in 2012 (4,623). Romania took third place, having added 645 hours to its total in 2013. Published in March 2014, this 146-page, PDF-delivered report covers 100 major formats on 84 channels across 16 European territories; with extensive comparison tables. -

TV Formats in Europe

TV Formats in Europe The value created for European broadcasters by the 100 major TV formats was $2,745 million in 2012. The 2012 figure was 5.3% up on the 2011 total, despite the number of hours broadcast increasing by 19.3%. Relative newcomer Money Drop was the top format title by value created in 2012; pushing Come Dine with Me into second place. The TV Formats in Europe report further states that The Voice entered the top 10 in 2012. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire was the top title in both 2009 and 2010, but had dropped to ninth in 2012. Endemol ($711 million – 26% of the total) was the leading distributor by value created in 2012, followed by FremantleMedia ($456 million – 17%). ITV was third, with 10% of the total. So, these three distributors combined took 53% of the total value created. These top three distributors accounted for half of the format hours screened in 2012. ITV Studios (5,425 hours) is the largest distributor by hours, mainly due to Come Dine with Me. FremantleMedia (3,316 hours and supplier of 13 titles in the top 100) and Endemol (4,231 hours and 12 titles) followed. Published in March 2013, this 172-page (23% larger than the previous edition), PDF-delivered report covers 100 major formats (double the number covered in the previous edition) on 84 channels across 16 European territories; with extensive comparison tables. Territory profiles include: Analysis of the formats in that market Overview of the TV market and the main channels Revenue generated by the top 100 formats by channel and country (2009-2012) Total -

Donor Impact 2016

Donor Impact 2016 Development and Alumni Relations Office Shaping bright futures Donor Impact 2016 Contents Meet the team Thank you to In each edition of Donor Impact, we introduce you to some of the members of the Development and all supporters Welcome and thank you ..................3 Alumni Relations team. Student Fund successes...............4 & 5 Nicola McIlroy of Ulster Graduating scholars...................6 & 7 After working for a number of years Connecting with the US...............8 & 9 as an IT accessibility and usability University consultant and then as a mobile device Corporate impact . 10 & 11 test engineer, Nicola joined Ulster Lasting legacy ...........................12 University in 2009. She is responsible for managing, updating and maintaining the I am delighted to introduce the second edition of In loving memory ........................13 alumni database as well as the team’s website. Nicola is kept busy outside of Donor Impact, our publication designed to update Why our donors support Ulster...........14 work also with her two year old daughter. you, our supporters, on the impact your generosity is having on our students and subsequently on our Excellence at Ulster ......................15 Favourite food: a sweet and spicy tagine society as a whole. Guilty pleasure: watching Come Dine with Me It has been another exciting year, with increased awards made from Dream job as a child: astronaut our Ulster University Student Fund as well as increased support from (it’s never too late…) our corporate partners. Alison Snookes In challenging times, it is even more important that we have the valuable support of our graduates, staff and friends, support that Alison has spent most of her career encourages and rewards excellence and opens up opportunities for our to date working in the Middle East, students to significantly enhance their academic experience at Ulster most recently as a business instructor University. -

TV Azteca/Comarex: Four Telenovelas and More…

12 PRENSARIO INTERNATIONAL PRENSARIO INTERNATIONAL 12 COMMENTARY WELCOME TO THE NEW CEE CONTENT MARKET I want to be honest with you, our read- showing this evolution, full of top broad- ers… when we had to start preparing this caster testimonies, figures and reports Natpe Budapest issue, we were a bit disap- that we’ve never got so good before in pointed, because many companies speak the region. As you know, our publication bad about the event, and the moment of is based in Latin America, and having so Central & Eastern Europe is not good, with strong participation from CEE broad- the economical crisis going on. But when casters and big content players, it is a big we began making interviews and articles, satisfaction for us. Even at the other side we’ve got feeling better and better. of the Atlantic Ocean, it is very difficult On one hand, in Central and Eastern for us to generate an edition so rich like Europe is being developed a huge new this one. Please read it and take your own market, full of investments and new TV opinion… channels, a real new media multiplatform environment. Now there is no money, THE BASICS but soon, when the situation gets better, For those reading Prensario Interna- a bubbling river of opportunities and tional for the first time… this publica- emerging businesses will take the tion is based on Latin America as I said, scene. It is a question of waiting… but has more than 20 years covering the and of working from now. whole international market, and now it On the other hand, we could manages strong coverage and feedback make an unique edition from all regions. -

SBS Food Dec 20

WEEK 52: Sunday, 20 December - Saturday, 26 December 2020 ALL MARKETS Date Start Time Title Episode Title Digital Epg Synopsis Country of Origin Language Repeat Classification Closed Captions Subtitles 2020-12-20 0500 Africa On A Plate Maseru, Lesotho Chef Zama Memela finds herself in Maseru, the capital city of the mountain Kingdom of Lesotho. USA English-100 RPT PG Gordon's Ultimate Christmas Gordon prepares a spectacular set of Christmas dishes that include his recipe for the ultimate turkey, superb stuffing, perfectly cooked vegetables and a 2020-12-20 0530 Gordon's Ultimate Christmas UNITED KINGDOM English-100 Ep 1 stunning Christmas dessert. 2020-12-20 0635 Heston's Feasts Christmas Cooking maestro Heston Blumenthal creates his ultimate feast for Christmas using majestic dishes from history to create his menu. UNITED KINGDOM English-100 RPT PG Y Y Big Family Cooking Showdown The Butlands from Cornwall, Lees from Warrington, Gohil and Al-Sheikhs from London, and Whites from Scotland must each feed a family of four for a 2020-12-20 0730 The Big Family Cooking Showdown UNITED KINGDOM English-100 PG Series 2, The Ep 3 tenner - from the freezer! On the morning menu is a two metre high boiled egg with toast soldiers, a box of cereal fit for a giant, a wacky flavour mash-up of the traditional English fry 2020-12-20 0830 Heston's Fantastical Food Big Breakfast UNITED KINGDOM English-100 RPT PG Y up, and even an edible daily newspaper. Cooking Up A Fortune Series 1 It's the last day of the heat and one kitchen will win a place in the weekly final. -

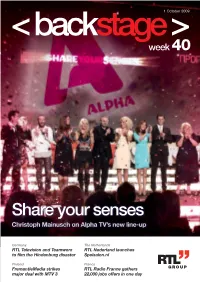

Share Your Senses Christoph Mainusch on Alpha TV’S New Line-Up

1 October 2009 week 40 Share your senses Christoph Mainusch on Alpha TV’s new line-up Germany The Netherlands RTL Television and Teamworx RTL Nederland launches to film the Hindenburg disaster Spelsalon.nl Finland France FremantleMedia strikes RTL Radio France gathers major deal with MTV 3 22,000 jobs offers in one day COVER: Alpha stars celebrating at the programme presentation on 24 September. 2 week 40 the RTL Group intranet “We are proud… and prepared” Alpha TV presented its new programming for the upcoming season. Backstage asked Christoph Mainusch, the new CEO of Alpha, what viewers can expect. Christoph Mainusch Greece - 1 October 2009 Many of the famous faces at Alpha attended the Apart from its perennially popular shows, Alpha special event on 24 September at the Egli cinema has introduced some new ones, like Pano stin at the Zappeion. Presenter Katerina Karavatou, ora (On Time) and Deste tous (Tie Them) and will who usually presents the gossip show introduce some more in the future, such as the Kous-Kous, hosted the programme presentation. Chart Show and Ten, which will run alternately Many of the channel’s major and minor stars lent every Sunday and originated from the famous her their support, taking the stage to add their German TV shows Die ultimative Chart Show and own amusing touches to the evening. Die Zehn which are broadcast on RTL Television. Commercial Director Costas Charitsis and Alpha’s new CEO, Christoph Mainusch, touched Now, as the new season begins, Backstage took briefly on the goals the station has set for the the opportunity to ask Christoph Mainusch about 2009/10 season. -

Gender Differences in Competitive Preferences: New Cross-Country Empirical Evidence

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bönte, Werner Working Paper Gender differences in competitive preferences: New cross-country empirical evidence Schumpeter Discussion Papers, No. 2014-008 Provided in Cooperation with: Schumpeter School of Business and Economics, University of Wuppertal Suggested Citation: Bönte, Werner (2014) : Gender differences in competitive preferences: New cross-country empirical evidence, Schumpeter Discussion Papers, No. 2014-008, University of Wuppertal, Schumpeter School of Business and Economics, Wuppertal, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:468-20140611-122840-4 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/104781 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents -

P32t Layout 1

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2014 TV PROGRAMS 18:00 Holmes On Homes 22:25 A.N.T. Farm 10:30 Clear And Present Danger- 18:50 Holmes On Homes 22:50 Shake It Up PG15 19:40 Phil Spencer: Secret Agent 23:10 Wolfblood 13:00 Iron Man 3-PG15 20:30 Rick Stein’s India 23:35 Wolfblood 15:15 Transformers-PG15 21:20 Come Dine With Me 00:30 The Daily Show Global 17:45 One Good Cop-PG15 00:50 Dark Days In Monkey City 22:10 Homes Under The Hammer Edition 20:00 Chain Reaction-PG15 01:15 Dark Days In Monkey City 23:05 Celebrity MasterChef 01:00 The Colbert Report Global 22:00 Safe-PG15 01:45 Monster Hammerhead 23:55 Celebrity MasterChef Edition 02:40 Reign Of The Dinosaurs 01:30 Saturday Night Live 03:35 The Pool Master 02:30 Girls 04:25 Too Cute! 00:30 Party On 03:00 Hot In Cleveland 05:15 Preposterous Pets 04:30 The Tonight Show Starring 06:02 Dark Days In Monkey City 00:55 Party On 01:25 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills Jimmy Fallon 00:00 The Hungover Games-R 06:25 Dark Days In Monkey City 07:00 Late Night With Seth Meyers 02:00 Death Becomes Her-PG15 06:49 Animal Cops Houston 00:45 Saint Hoods 01:50 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 01:35 How It’s Made 02:20 E! News 09:00 Hot In Cleveland 04:00 Mystery, Alaska-PG15 07:36 Call Of The Wildman 10:00 New Girl 06:00 Seeking A Friend For The 08:00 Animal Airport 06:00 Wheeler Dealers: Trading Up 03:15 Eric And Jessie: Game On 06:50 Extreme Car Hoarders 03:40 Eric And Jessie: Game On 11:00 The Tonight Show Starring End Of The World-PG15 08:25 Must Love Cats Jimmy Fallon 08:00 Look Who’s Talking Too- 09:15 My Pet’s Gone Viral