Originalism and Stare Decisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

85 Days of Prayer U.S

85 Days of Prayer U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Senate U.S. House of Rep. Name: Title: Name (Seated): Name (Party-State): Name (Party-State): Donald Trump President John G. Roberts, Jr. (9/29/05) Markey, Edward J. (D-MA) Heck, Denny (D-WA) Michael Pence Vice President Clarence Thomas (10/23/91) McConnell, Mitch (R-KY) Hern, Kevin (R-OK) Melania Trump First Lady Herrera Beutler, Jaime (R-WA) Sonny Perdue Secretary of Agriculture Michigan Supreme Court State of Michigan Hice, Jody B. (R-GA) William Barr Attorney General Bridget Mary McCormack Gretchen Whitmer (Governor) Higgins, Brian (D-NY) Sunday, November 01 November Sunday, Mark Meadows White House Chief of Staff Stephen Markman Garlin Gilchrist II (Lt. Governor) Higgins, Clay (R-LA) U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Senate U.S. House of Rep. Name: Title: Name (Seated): Name (Party-State): Name (Party-State): Donald Trump President Stephen G. Breyer (8/3/94) McSally, Martha (R-AZ) Hill, J. French (R-AR) Michael Pence Vice President Samuel A. Alito (1/31/06) Menendez, Robert (D-NJ) Himes, James A. (D-CT) Gina Haspel Director of the CIA Holding, George (R-NC) Wilbur L. Ross Jr. Secretary of Commerce Michigan Supreme Court State of Michigan Hollingsworth, Trey (R-IN) Mark Esper Secretary of Defense Brian Zahra Jocelyn Benson (Sec. of State) Horn, Kendra S. (D-OK) Monday, November 02 November Monday, Kayleigh McEnany Press Secretary David Viviano Dana Nessel (Attorney Gen.) Horsford, Steven (D-NV) U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. -

V-9 Stephen J. Markman

JUSTICE STEPHEN J. MARKMAN Term expires January 1, 2013 Stephen Markman was appointed as a justice of the Michigan Supreme Court on October 1, 1999. Before his appointment, he served as judge on the Michigan Court of Appeals from 1995-1999. Prior to this, he prac- ticed law with the firm of Miller, Canfield, Paddock & Stone in Detroit. From 1989-93, Justice Markman served as United States Attorney, or federal prosecutor, in Michigan, after having been nominated by President George H. W. Bush and confirmed by the United States Senate. From 1985-1989, he served as Assistant Attorney General of the United States, after having been nominated by President Ronald Reagan and confirmed by the United States Senate. In that position, he headed the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Policy, which served as the principal policy development office within the Department, and which coordinated the federal judicial selection process. Prior to this, he served for 7 years as Chief Counsel of the United States Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution, and as Deputy Chief Counsel of the United States Senate Judiciary Committee. Justice Markman has authored articles for such publications as the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, the Detroit College of Law Review, the Stanford Law Review, the University of Chicago Law Review, the American Criminal Justice Law Review, the Barrister’s Law Journal, the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, and the American University Law Review. He has also served as a contributing editor of National Review magazine, and has authored chapters in such books as “In the Name of Justice: The Aims of the Criminal Law,” “Still the Law of the Land,” and “Originalism: A Quarter Century of Debate.” Justice Markman has taught constitutional law at Hillsdale College since 1993. -

Politics:Three Weeks to "E"

2012 General Election “A Pollster’s Perspective” U.P. Energy Conference October 16, 2012 By Steve Mitchell, President Mitchell Research & Communications, Inc. PRESIDENTIAL RACE NATIONAL/MICHIGAN PAST & PRESENT Presidential Candidates Romney/Ryan vs. Obama/Biden Presidential Election 2012 70 61.6 60 46.3 47.3 48.8 44.4 50 39.2 40 Obama 30 Romney 20 10 0 RCP National RCP Michigan Intrade Odds Average Average Electoral Vote Margin Toss Up States Most Recent Polling Averages Obama Romney Spread Nevada 48.2 46.6 +1.6 Iowa 48.6 45.4 +3.2 Ohio 47.6 46.3 +1.3 Virginia 48.0 47.6 +.4 New Hampshire 48.0 47.3 +.7 Colorado 47.0 47.7 -.7 North Carolina 46.0 49.3 -3.3 2012 vs. 2004 Likely Voters 2012--“Suppose the presidential election were held today. If Barack Obama were the Democratic Party’s candidate and Mitt Romney were the Republican Party’s candidate, who would you vote for Barack Obama, the Democrat or Mitt Romney, the Republican?” 2004--(Asked of Nader voters) “If Ralph Nader is not on the ballot in your state on Election Day, would you vote for – Kerry and Edwards, the Democrats (or) Bush and Cheney, the Republicans? As of today, do you lean more toward – Kerry and Edwards, the Democrats (or) Bush and Cheney, the Republicans?” % 35 40 45 50 55 60 29-Jun LikelyVoters vs. 2004 2012 6-Jul of Voters Likely 2004 Presidential 2012 vs. Election 13-Jul 20-Jul 27-Jul 3-Aug 10-Aug 17-Aug 24-Aug 31-Aug 7-Sep 14-Sep 21-Sep 28-Sep 5-Oct 12-Oct 19-Oct 26-Oct 2-Nov Kerry Bush Obama Romney MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT Michigan Supreme Court The Michigan Supreme Court currently has 4 Republicans and 3 Democrats giving the Republicans control. -

Is the Sun Setting on Tort Reform Laws? Not If Michigan Physicians… Doc the Ote

AWARD-WINNING MAGAZINE OF THE MICHIGAN STATE MEDICAL SOCIETY September/October 2012 • Volume 111 • No. 5 msms.orgWWW MichiganMedicine Is the Sun Setting on Tort Reform Laws? Not if Michigan Physicians… DOC THE OTE ALSO IN THIS ISSUE • The Effect of Payment Reform on Physician Practices – Part 1 • Why the Supreme Court Race is Important • Recommendations for the Management of HBV-Infected Health Care Providers II MICHIGAN MEDICINE September/October 2012 Volume 111 • Number 5 MICHIGAN MEDICINE 1 Executive Director Julie l. Novak Committee on Publications lYNN S. GRaY, MD, MPH, Chair, Berrien Springs MichiganMedicine MiCHAEL J. eHLERT, MD, livonia September/October 2012 • Volume 111 • Number 5 THeODORe B. JONeS, MD, Detroit BaSSaM NaSR, MD, MBa, Port Huron COVER STORY STeVeN e. NeWMaN, MD, Southfield PeGGYaNN NOWAK, MD, West Bloomfield 9 Philosophy Matters By Stacy Sellek Director of Communications During this election cycle, it’s crucial for physicians to become as informed and engaged as & Media Relations possible in the Michigan Supreme Court race. MDPAC-endorsed candidates Justice Stephen Jessy J. SielSki Markman, Justice Brian Zahra, and Judge Colleen O’Brien tell MSMS’s Stacy Sellek why. email: [email protected] Publication Office FEATURES Michigan State Medical Society 14 The Effect of Payment Reform on Physician Practices – Part 1 PO Box 950, east lansing, Mi 48826-0950 Contributors: Stacey Hettiger, Joe Neller and Paul Natinsky 517-337-1351 In part one of this three-part series, our contributors describe the trends in physician www.msms.org reimbursement, particularly the shift from fee-for-service to outcomes-based. all communications on articles, news, exchanges In upcoming issues, we’ll examine the role physician organizations and incentive and classified advertising should be sent to the above programs will play in how physicians choose to practice medicine. -

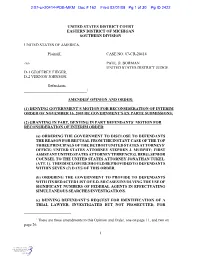

S:\Judges Folder\Fieger.Jan2.Order.2Revised.Wpd

2:07-cr-20414-PDB-MKM Doc # 162 Filed 02/01/08 Pg 1 of 30 Pg ID 2422 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, CASE NO. 07-CR-20414 -vs- PAUL D. BORMAN UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE D-1 GEOFFREY FIEGER, D-2 VERNON JOHNSON, Defendants. ________________________________/ AMENDED1 OPINION AND ORDER: (1) DENYING GOVERNMENT’S MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF INTERIM ORDER OF NOVEMBER 16, 2005 RE GOVERNMENT’S EX PARTE SUBMISSIONS; (2) GRANTING IN PART, DENYING IN PART DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF INTERIM ORDER: (a) ORDERING THE GOVERNMENT TO DISCLOSE TO DEFENDANTS THE REASON FOR RECUSAL FROM THE INSTANT CASE OF THE TOP THREE PRINCIPALS OF THE DETROIT UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS’ OFFICE; UNITED STATES ATTORNEY STEPHEN J. MURPHY; FIRST ASSISTANT UNITED STATES ATTORNEY TERRENCE G. BERG; SENIOR COUNSEL TO THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY JONATHAN TUKEL. (ATT. 1). THIS DISCLOSURE SHOULD BE PROVIDED TO DEFENDANTS WITHIN SEVEN (7) DAYS OF THIS ORDER. (b) ORDERING THE GOVERNMENT TO PROVIDE TO DEFENDANTS WITH ITS REDACTED LIST OF E.D. MI CASES INVOLVING THE USE OF SIGNIFICANT NUMBERS OF FEDERAL AGENTS IN EFFECTUATING SIMULTANEOUS SEARCHES/INVESTIGATIONS. (c) DENYING DEFENDANT’S REQUEST FOR IDENTIFICATION OF A TRIAL LAWYER, INVESTIGATED BUT NOT PROSECUTED, FOR 1 There are three amendments to this Opinion and Order, one on page 11, and two on page 26. 1 2:07-cr-20414-PDB-MKM Doc # 162 Filed 02/01/08 Pg 2 of 30 Pg ID 2423 ILLEGAL FEDERAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE 2004 EDWARDS FOR PRESIDENT CAMPAIGN. Before the Court is Defendant Fieger’s Motion for Reconsideration regarding the Court’s Interim Order on Discovery (Doc. -

The Company They Keep: How Partisan

The Company They Keep: How Partisan Divisions Came to the Supreme Court Neal Devins, College of William and Mary Lawrence Baum, Ohio State University Table of Contents Chapter 1: Summary of Book and Argument 1 Chapter 2: The Supreme Court and Elites 21 Chapter 3: Elites, Ideology, and the Rise of the Modern Court 100 Chapter 4: The Court in a Polarized World 170 Chapter 5: Conclusions 240 Chapter 1 Summary of Book and Argument On September 12, 2005, Chief Justice nominee John Roberts told the Senate Judiciary Committee that “[n]obody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire. I will 1 remember that it’s my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.” Notwithstanding Robert’s paean to judicial neutrality, then Senator Barack Obama voted against the Republican nominee. Although noting that Roberts was “absolutely . qualified,” Obama said that what mattered was the “5 percent of hard cases,” cases resolved not by adherence to legal rules but decided by “core concerns, one’s broader perspectives of how the world works, and the depth and breadth of one’s empathy.”2 But with all 55 Republicans backing Roberts, Democratic objections did not matter. Today, the dance between Roberts and Senate Democrats and Republicans seems so predictable that it now seems a given that there will be proclamations of neutrality by Supreme Court nominees and party line voting by Senators. Indeed, Senate Republicans blocked a vote on Obama Supreme Court pick Merrick Garland in 2016 so that (in the words of Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell) “the American people . -

Crain's Detroit Busi N Ess

10t5t2020 Printable CRAIN'S DETROIT BUSI N ESS You may not reproduce, display on a website, distribute, sell or republish this article or data, or the information contained therein, without prior written consent. This printout and/or PDF is for personal usage only and not for any promotional usage. @ Crain Communications lnc. october 04,2o2o 06:38 PM I UeOnreo 41 MINUTES AGO Whitmer's COVID executive orders are out. Here are the pandemic restrictions still in. CHAD LIVENGOOD tr [ " Multiple legal avenues available to continue restrictions on business activity " None are nearly as broad and sweeping as a governor's executive orders " Counties are issuing orders after state Supreme Court ruled against Whitmer Chad Livengood/Craln's Detroit Businoss Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's executive order requiring customers and workers to wear masks inside indoor businesses is no longer enforceable after the Michigan Supreme Court struck down the law she used to impose the order, Attorney General Dana Nessel said Sunday. Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel announced Sunday that she will not enforce any of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's pandemic executive orders after the Michigan Supreme Court narrowly ruled that the governor has exceeded her authority for the past five months in managing the coronavirus pandemic. But that doesn't mean all government rules and regulations aimed at mitigating the spread of the airborne virus have gone away for businesses, schools and individuals. From the state public health code to business licensing and local health orders, there are multiple legal avenues for continued restrictions on business activity, though none nearly as broad and sweeping as a governor's executive orders. -

Limits of Interpretivism Richard A

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2009 Limits of Interpretivism Richard A. Primus University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/521 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Judges Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Primus, Richard A. "Limits of Interpretivism." Harv. J. L. & Pub. Pol'y 32, no. 1 (2009): 159-77. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMITS OF INTERPRETIVISM RICHARD PRIMUS* INTRODUCTION ............................................................ 159 I. INTERPRETIVISM AND TEXTUALISM ...................... 161 II. TEXTUALISM AND RULES ...................................... 164 III. TEXTUALISM AND ORIGINALISM .......................... 168 IV. ORIGINALISM AND CONSTRAINT ......................... 170 V. ORIGINALISM AND TRADITION ............................. 173 C O N CLU SIO N ................................................................ 176 INTRODUCTION Justice Stephen Markman sits on the Supreme Court of my home state of Michigan. In that capacity, he says, he is involved in a struggle between two kinds of judging. On one side are judges like him. They follow the rules. On the other side are unconstrained judges who decide cases on the basis of what they think the law ought to be.1 This picture is relatively sim- ple, and Justice Markman apparently approves of its simplic- ity. -

Society Update the Official Publication of the Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society

Society Update The Official Publication of the Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society Fall 2018 Justice Young’s Portrait Unveiled On Wednesday, November 28, 2018, the portrait of former Michigan Supreme Court Chief Justice Robert P. Young, Jr. was unveiled in a special session of the Michigan Supreme Court. Young was appointed to the Michigan Supreme Court on January 2, 1999, by then-Governor John Engler. He won election to the remainder of that term in 2000, and to eight-year terms in 2002 and 2010. Young was elected chief justice by the other justices each January from 2011 through 2017. He is the lon- gest consecutively-serving chief justice in Michigan Supreme Court history. Justice Young retired from the Michigan Supreme Court in April 2017. In June 2018, he joined Michi- gan State University as vice president for legal affairs and general counsel. The portrait dedication ceremony included re- marks from former justices Maura Corrigan and Clif- ford Taylor as well as former Governor John Engler and current justices Brian Zahra, Bridget McCor- mack, and Chief Justice Stephen Markman. Justice Young was joined at the special session by his wife, Dr. Linda Hotchkiss, their two sons, and The official portrait of former Chief Justice Robert P. many other family and friends including several for- Young, Jr., painted by the late Patricia Hill Burnett, cur- mer law clerks. rently hangs in the Michigan Supreme Court Learning Center on the first floor of the Hall of Justice. Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society Justice Young visits with Court of Appeals judges Mi- Justice Young poses with Lansing Judge Donald Allen chael Riordan (L), Michael Gadola (C), and Attorney at the reception held in the first floor conference cen- General Eric Restuccia (R) at the reception before the ter at the Hall of Justice. -

The Federal Judicial Vacancy Crisis: Origins and Solutions

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 The edeF ral Judicial Vacancy Crisis: Origins and Solutions Ryan Shaffer Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Shaffer, Ryan, "The eF deral Judicial Vacancy Crisis: Origins and Solutions" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 321. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/321 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE THE FEDERAL JUDICIAL VACANCY CRISIS: ORIGINS AND SOLUTIONS SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR JOHN J. PITNEY, JR. AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY RYAN SHAFFER FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING 2012 APRIL 23, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: OBAMA’S VACANCY CRISIS . 1 I. THE FOUNDERS’ JUDICIARY . 6 II. JURISPRUDENCE FROM MARSHALL TO WARREN . 10 III. FORTAS AND NIXON . 23 IV. DRAWING THE BATTLE LINES . 32 V. ESCALATION: BUSH AND CLINTON . 41 VI. THE CONFLICT GOES NUCLEAR: BUSH AND OBAMA . 50 VII. FIXING ADVICE AND CONSENT . 60 CONCLUSION . 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 67 INTRODUCTION: OBAMA’S VACANCY CRISIS On January 20 th , 2009, Barack Obama’s first day in the White House, there were 55 vacancies in the federal judicial system. His first nomination, of David Hamilton for the Seventh Circuit, came only two months later; Hamilton did not win confirmation until November 19 th , 59-39, with only one Republican supporter. By September, the number of vacancies had jumped to 93; the administration had made 16 nominations, with no confirmations. For all of 2010, the number of judicial vacancies would remain above 100, of 874 authorized judgeships, and for more than half of those seats, the administration had not even submitted nominees. -

85 Days of Prayer US Supreme Court US Senate US House of Rep

85 Days of Prayer U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Senate U.S. House of Rep. Name: Title: Name (Seated): Name (Party-State): Name (Party-State): Donald Trump President John G. Roberts, Jr. (9/29/05) Alexander, Lamar (R-TN) Abraham, Ralph Lee (R-LA) Michael Pence Vice President Clarence Thomas (10/23/91) Baldwin, Tammy (D-WI) Adams, Alma S. (D-NC) Melania Trump First Lady Aderholt, Robert B. (R-AL) Sonny Perdue Secretary of Agriculture Michigan Supreme Court State of Michigan Aguilar, Pete (D-CA) William Barr Attorney General Bridget Mary McCormack Gretchen Whitmer (Governor) Allen, Rick W. (R-GA) Sunday, October 04 October Sunday, Mark Meadows White House Chief of Staff Stephen Markman Garlin Gilchrist II (Lt. Governor) Allred, Colin Z. (D-TX) U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Senate U.S. House of Rep. Name: Title: Name (Seated): Name (Party-State): Name (Party-State): Donald Trump President Stephen G. Breyer (8/3/94) Barrasso, John (R-WY) Amash, Justin (L-MI) Michael Pence Vice President Samuel A. Alito (1/31/06) Bennet, Michael F. (D-CO) Amodei, Mark E. (R-NV) Gina Haspel Director of the CIA Armstrong, Kelly (R-ND) Wilbur L. Ross Jr. Secretary of Commerce Michigan Supreme Court State of Michigan Arrington, Jodey C. (R-TX) Mark Esper Secretary of Defense Brian Zahra Jocelyn Benson (Sec. of State) Axne, Cynthia (D-IA) Monday, October 05 October Monday, Kayleigh McEnany Press Secretary David Viviano Dana Nessel (Attorney Gen.) Babin, Brian (R-TX) U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. -

Michigan Supreme Court May Settle Issue of Public Aid for Private Schools

Michigan Supreme Court may settle issue of public aid for private schools Jonathan Oosting, The Detroit News Published 9:12 a.m. ET June 25, 2019 | Updated 7:21 p.m. ET June 25, 2019 Michigan’s Supreme Court on Jan. 1, 2019: L-R by row from top, justices Brian Zahra, Richard Bernstein, Megan Cavanagh, Elizabeth Clement, David Viviano, Bridget Mary McCormack and chief justice Stephen Markman. (Photo: Rod Sanford, Special to The Detroit News) Lansing — The Michigan Supreme Court has agreed to reconsider a high-stakes case that tests the limits of the state’s constitutional ban on using public taxpayer money to support private school education. At issue is $5 million in funding approved by Michigan’s Republican-led Legislature to reimburse religious and other non-public schools for state mandates that do not directly support student education. Public school advocates argue the spending is a “slippery slope” and sued the state in 2017 over an initial $2.5 million appropriation to reimburse private schools for fire drills, inspections and other state requirements. Lawmakers later approved another $2.5 million for fiscal year 2018. A divided state Court of Appeals panel upheld the spending in October 2018, ruling the state can reimburse private schools for “incidental” costs that do not support a “primary” function critical to the school's existence or result in “excessive religious entanglement.” Plaintiffs challenged the ruling, and the state Supreme Court on Tuesday granted their application for leave to appeal. In doing so, Justice Stephen Markman said allowing the state funding plan to proceed “would perhaps be in tension with the Establishment Clause” of the U.S.