Dangerous Secrets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting Agenda.Indd

SEABOTA 2021 Annual Conference Henderson Beach Resort & Spa, Destin, Florida Meeting Agenda Friday, September 17 8:30 am - 8:35 am Conference Overview and Welcome S. Lester, Tate, III, President September 17 -18, 2021 8:35 am - 8:50 am Introductions of Attendees S. Lester Tate, III, President Thank you to our sponsor: 8:50 am - 9:20 am Trial By Jury Justice John Ellington Georgia Supreme Court 9:20 am - 9:50 am Some Thoughts on the Future . of Jury Trials Justice John Cannon Few South Carolina Supreme Court 9:50 am - 10:05 am Panel Q&A with Justice John Ellington and Justice John Cannon Few Moderated by S. Lester, Tate III 10:05 am - 10:15 am Coff ee Break The Foundation of ABOTA has applied for 10:15 am - 10:45 am Who Killed the Swains?: Dennis Perry’s CLE in all SEABOTA states: 20-year fi ght for Justice Joshua Sharpe CLE Approvals The Atlanta Journal-Constitution • Alabama 4.1 general credit hours • Arkansas 4 general credit hours 10:45 am - 10:55 am National Report • Georgia 4 general credit hours Grace Weatherly, National President • Kentucky 4 general credit hours • Louisiana 4 general credit hours 10:55 am - 11:05 am Foundation Report • Mississippi 4.1 general credit hours Douglas M. DeGrave, Foundation President • North Carolina 4 general credit hours • South Carolina 4.08 general credit hours 11:05 am - 12:15 pm Break • Tennessee 5.33 general credit hours • Virginia 2.5 general credit hours 12:15 pm - 1:15 pm Bourbon Justice: How Whiskey Shaped American Law with Brian F. -

28Th Annual Criminal Practice in South Carolina Friday, February 22, 2019

28th Annual Criminal Practice in South Carolina Friday, February 22, 2019 presented by The South Carolina Bar Continuing Legal Education Division http://www.scbar.org/CLE SC Supreme Court Commission on CLE Course No. 190837 Table of Contents Agenda ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Faculty Bios ......................................................................................................................................... 5 State Criminal Practice: Significant Developments in 2018 ..........................................................15 Federal Criminal Practice : Significant Developments in 2018 .....................................................32 Legislative Review and Preview: Significant 2018 Legislation, Pre-Filed Bills for 2019, and Rule Changes ...............................................................................................................................................37 Amie Clifford, Tommy Pope Expungements Primer .......................................................................................................................61 Adam Whitsett Developments and Issues in Juveniles Justice .................................................................................84 L. Eden Hendrick Keeping Up with Trends and Issues in Criminal Defense ............................................................104 Christopher Adams PCR-Proofing Your Case ................................................................................................................112 -

85 Days of Prayer U.S

85 Days of Prayer U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Senate U.S. House of Rep. Name: Title: Name (Seated): Name (Party-State): Name (Party-State): Donald Trump President John G. Roberts, Jr. (9/29/05) Markey, Edward J. (D-MA) Heck, Denny (D-WA) Michael Pence Vice President Clarence Thomas (10/23/91) McConnell, Mitch (R-KY) Hern, Kevin (R-OK) Melania Trump First Lady Herrera Beutler, Jaime (R-WA) Sonny Perdue Secretary of Agriculture Michigan Supreme Court State of Michigan Hice, Jody B. (R-GA) William Barr Attorney General Bridget Mary McCormack Gretchen Whitmer (Governor) Higgins, Brian (D-NY) Sunday, November 01 November Sunday, Mark Meadows White House Chief of Staff Stephen Markman Garlin Gilchrist II (Lt. Governor) Higgins, Clay (R-LA) U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Senate U.S. House of Rep. Name: Title: Name (Seated): Name (Party-State): Name (Party-State): Donald Trump President Stephen G. Breyer (8/3/94) McSally, Martha (R-AZ) Hill, J. French (R-AR) Michael Pence Vice President Samuel A. Alito (1/31/06) Menendez, Robert (D-NJ) Himes, James A. (D-CT) Gina Haspel Director of the CIA Holding, George (R-NC) Wilbur L. Ross Jr. Secretary of Commerce Michigan Supreme Court State of Michigan Hollingsworth, Trey (R-IN) Mark Esper Secretary of Defense Brian Zahra Jocelyn Benson (Sec. of State) Horn, Kendra S. (D-OK) Monday, November 02 November Monday, Kayleigh McEnany Press Secretary David Viviano Dana Nessel (Attorney Gen.) Horsford, Steven (D-NV) U.S. Executive Branch: U.S. -

V-9 Stephen J. Markman

JUSTICE STEPHEN J. MARKMAN Term expires January 1, 2013 Stephen Markman was appointed as a justice of the Michigan Supreme Court on October 1, 1999. Before his appointment, he served as judge on the Michigan Court of Appeals from 1995-1999. Prior to this, he prac- ticed law with the firm of Miller, Canfield, Paddock & Stone in Detroit. From 1989-93, Justice Markman served as United States Attorney, or federal prosecutor, in Michigan, after having been nominated by President George H. W. Bush and confirmed by the United States Senate. From 1985-1989, he served as Assistant Attorney General of the United States, after having been nominated by President Ronald Reagan and confirmed by the United States Senate. In that position, he headed the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Policy, which served as the principal policy development office within the Department, and which coordinated the federal judicial selection process. Prior to this, he served for 7 years as Chief Counsel of the United States Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution, and as Deputy Chief Counsel of the United States Senate Judiciary Committee. Justice Markman has authored articles for such publications as the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, the Detroit College of Law Review, the Stanford Law Review, the University of Chicago Law Review, the American Criminal Justice Law Review, the Barrister’s Law Journal, the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, and the American University Law Review. He has also served as a contributing editor of National Review magazine, and has authored chapters in such books as “In the Name of Justice: The Aims of the Criminal Law,” “Still the Law of the Land,” and “Originalism: A Quarter Century of Debate.” Justice Markman has taught constitutional law at Hillsdale College since 1993. -

Originalism and Stare Decisis

ORIGINALISM AND STARE DECISIS STEPHEN MARKMAN* The extent to which originalism can be harmonized with precedent is an issue I have confronted regularly during my ten‐ ure as a justice on the Michigan Supreme Court. This article out‐ lines several observations that have informed my thinking on this topic, drawn from my decade or so on that court.1 I view myself as an originalist judge, sometimes lapsing into self‐descriptions as a “textualist,” an “interpretivist,” a believer in “original meaning,” or even a “judicial conservative.” Nu‐ ances of differences in these terms aside, I take seriously what I view as my obligation to give reasonable meaning to the lan‐ guage of the drafters of constitutions, statutes, contracts, and deeds. I have taken oaths to the United States Constitution and to the Michigan Constitution, and I take these oaths seriously. On the other hand, I have not taken an oath to abide by the judgments of my predecessors. Yet, on a number of occasions, I have sustained precedents I have disagreed with, and which did not, in my judgment, conform to the intentions of the lawmaker. Despite this, the primary criticism of my court during the eight years when I served with three other originalists as a majority of our seven‐member court, was that we were insufficiently re‐ spectful of precedent.2 Throughout my time on the court, I have * Justice, Michigan Supreme Court. Based on remarks delivered at the Twenty‐Ninth Annual Federalist Society National Student Symposium, held at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. 1. The author was appointed to the Michigan Supreme Court on October 1, 1999, and reelected in 2000 and 2004. -

Politics:Three Weeks to "E"

2012 General Election “A Pollster’s Perspective” U.P. Energy Conference October 16, 2012 By Steve Mitchell, President Mitchell Research & Communications, Inc. PRESIDENTIAL RACE NATIONAL/MICHIGAN PAST & PRESENT Presidential Candidates Romney/Ryan vs. Obama/Biden Presidential Election 2012 70 61.6 60 46.3 47.3 48.8 44.4 50 39.2 40 Obama 30 Romney 20 10 0 RCP National RCP Michigan Intrade Odds Average Average Electoral Vote Margin Toss Up States Most Recent Polling Averages Obama Romney Spread Nevada 48.2 46.6 +1.6 Iowa 48.6 45.4 +3.2 Ohio 47.6 46.3 +1.3 Virginia 48.0 47.6 +.4 New Hampshire 48.0 47.3 +.7 Colorado 47.0 47.7 -.7 North Carolina 46.0 49.3 -3.3 2012 vs. 2004 Likely Voters 2012--“Suppose the presidential election were held today. If Barack Obama were the Democratic Party’s candidate and Mitt Romney were the Republican Party’s candidate, who would you vote for Barack Obama, the Democrat or Mitt Romney, the Republican?” 2004--(Asked of Nader voters) “If Ralph Nader is not on the ballot in your state on Election Day, would you vote for – Kerry and Edwards, the Democrats (or) Bush and Cheney, the Republicans? As of today, do you lean more toward – Kerry and Edwards, the Democrats (or) Bush and Cheney, the Republicans?” % 35 40 45 50 55 60 29-Jun LikelyVoters vs. 2004 2012 6-Jul of Voters Likely 2004 Presidential 2012 vs. Election 13-Jul 20-Jul 27-Jul 3-Aug 10-Aug 17-Aug 24-Aug 31-Aug 7-Sep 14-Sep 21-Sep 28-Sep 5-Oct 12-Oct 19-Oct 26-Oct 2-Nov Kerry Bush Obama Romney MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT Michigan Supreme Court The Michigan Supreme Court currently has 4 Republicans and 3 Democrats giving the Republicans control. -

Is the Sun Setting on Tort Reform Laws? Not If Michigan Physicians… Doc the Ote

AWARD-WINNING MAGAZINE OF THE MICHIGAN STATE MEDICAL SOCIETY September/October 2012 • Volume 111 • No. 5 msms.orgWWW MichiganMedicine Is the Sun Setting on Tort Reform Laws? Not if Michigan Physicians… DOC THE OTE ALSO IN THIS ISSUE • The Effect of Payment Reform on Physician Practices – Part 1 • Why the Supreme Court Race is Important • Recommendations for the Management of HBV-Infected Health Care Providers II MICHIGAN MEDICINE September/October 2012 Volume 111 • Number 5 MICHIGAN MEDICINE 1 Executive Director Julie l. Novak Committee on Publications lYNN S. GRaY, MD, MPH, Chair, Berrien Springs MichiganMedicine MiCHAEL J. eHLERT, MD, livonia September/October 2012 • Volume 111 • Number 5 THeODORe B. JONeS, MD, Detroit BaSSaM NaSR, MD, MBa, Port Huron COVER STORY STeVeN e. NeWMaN, MD, Southfield PeGGYaNN NOWAK, MD, West Bloomfield 9 Philosophy Matters By Stacy Sellek Director of Communications During this election cycle, it’s crucial for physicians to become as informed and engaged as & Media Relations possible in the Michigan Supreme Court race. MDPAC-endorsed candidates Justice Stephen Jessy J. SielSki Markman, Justice Brian Zahra, and Judge Colleen O’Brien tell MSMS’s Stacy Sellek why. email: [email protected] Publication Office FEATURES Michigan State Medical Society 14 The Effect of Payment Reform on Physician Practices – Part 1 PO Box 950, east lansing, Mi 48826-0950 Contributors: Stacey Hettiger, Joe Neller and Paul Natinsky 517-337-1351 In part one of this three-part series, our contributors describe the trends in physician www.msms.org reimbursement, particularly the shift from fee-for-service to outcomes-based. all communications on articles, news, exchanges In upcoming issues, we’ll examine the role physician organizations and incentive and classified advertising should be sent to the above programs will play in how physicians choose to practice medicine. -

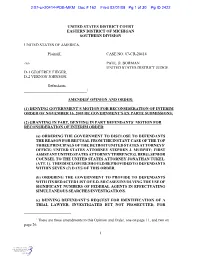

S:\Judges Folder\Fieger.Jan2.Order.2Revised.Wpd

2:07-cr-20414-PDB-MKM Doc # 162 Filed 02/01/08 Pg 1 of 30 Pg ID 2422 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, CASE NO. 07-CR-20414 -vs- PAUL D. BORMAN UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE D-1 GEOFFREY FIEGER, D-2 VERNON JOHNSON, Defendants. ________________________________/ AMENDED1 OPINION AND ORDER: (1) DENYING GOVERNMENT’S MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF INTERIM ORDER OF NOVEMBER 16, 2005 RE GOVERNMENT’S EX PARTE SUBMISSIONS; (2) GRANTING IN PART, DENYING IN PART DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF INTERIM ORDER: (a) ORDERING THE GOVERNMENT TO DISCLOSE TO DEFENDANTS THE REASON FOR RECUSAL FROM THE INSTANT CASE OF THE TOP THREE PRINCIPALS OF THE DETROIT UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS’ OFFICE; UNITED STATES ATTORNEY STEPHEN J. MURPHY; FIRST ASSISTANT UNITED STATES ATTORNEY TERRENCE G. BERG; SENIOR COUNSEL TO THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY JONATHAN TUKEL. (ATT. 1). THIS DISCLOSURE SHOULD BE PROVIDED TO DEFENDANTS WITHIN SEVEN (7) DAYS OF THIS ORDER. (b) ORDERING THE GOVERNMENT TO PROVIDE TO DEFENDANTS WITH ITS REDACTED LIST OF E.D. MI CASES INVOLVING THE USE OF SIGNIFICANT NUMBERS OF FEDERAL AGENTS IN EFFECTUATING SIMULTANEOUS SEARCHES/INVESTIGATIONS. (c) DENYING DEFENDANT’S REQUEST FOR IDENTIFICATION OF A TRIAL LAWYER, INVESTIGATED BUT NOT PROSECUTED, FOR 1 There are three amendments to this Opinion and Order, one on page 11, and two on page 26. 1 2:07-cr-20414-PDB-MKM Doc # 162 Filed 02/01/08 Pg 2 of 30 Pg ID 2423 ILLEGAL FEDERAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE 2004 EDWARDS FOR PRESIDENT CAMPAIGN. Before the Court is Defendant Fieger’s Motion for Reconsideration regarding the Court’s Interim Order on Discovery (Doc. -

2021 It's All a Game: Top Trial Lawyers Tackle Evidence

2021 It’s All A Game: Top Trial Lawyers Tackle Evidence 21-04 Friday, February 19, 2021 presented by The South Carolina Bar Continuing Legal Education Division http://www.scbar.org/CLE SC Supreme Court Commission on CLE Course No. 213780ADO This program qualifies for 6.0 MCLE credit hours, including up to 1.0 LEPR credit hour. SC Supreme Commission on CLE Course #: 213780ADO 8:50 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks The Honorable John Cannon Few, Justice, Supreme Court of South Carolina 9:00 a.m. The Sound of Silence: The Fifth Amendment and the Right to Remain Silent Original Presentation ~ 2020 Andrew B. Moorman Sr., Moorman Law Firm 10:00 a.m. You Can't Handle the Truth!!!: Effective ways for dealing with difficult, hostile or adverse witnesses Breon C.M. Walker, The Stanley Law Group, P.A. He's Quite a Character, Have You Heard What He's Done?: The use of character in criminal trials, how a prosecutor plans to use it in her case in chief, and what (if anything) you can do about it! Meghan L. Walker, Executive Director, South Carolina State Ethics Commission Original Presentations ~ 2014 11:00 a.m. Break 11:15 a.m. Forensic Interviews and Child Hearsay Statutes: What's Fair, What's Foul, and Are More Problems Yet to Come? Original Presentation ~ 2015 The Honorable Blake A. Hewitt, South Carolina Court of Appeals 12:15 p.m. Lunch Break 1:30 p.m. Managing the Changing Scope of Relevance in a Trial: Innovative Challenges to Traditional Concept of Admissibility? Original Presentation ~ 2008 The Honorable A. -

The Company They Keep: How Partisan

The Company They Keep: How Partisan Divisions Came to the Supreme Court Neal Devins, College of William and Mary Lawrence Baum, Ohio State University Table of Contents Chapter 1: Summary of Book and Argument 1 Chapter 2: The Supreme Court and Elites 21 Chapter 3: Elites, Ideology, and the Rise of the Modern Court 100 Chapter 4: The Court in a Polarized World 170 Chapter 5: Conclusions 240 Chapter 1 Summary of Book and Argument On September 12, 2005, Chief Justice nominee John Roberts told the Senate Judiciary Committee that “[n]obody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire. I will 1 remember that it’s my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.” Notwithstanding Robert’s paean to judicial neutrality, then Senator Barack Obama voted against the Republican nominee. Although noting that Roberts was “absolutely . qualified,” Obama said that what mattered was the “5 percent of hard cases,” cases resolved not by adherence to legal rules but decided by “core concerns, one’s broader perspectives of how the world works, and the depth and breadth of one’s empathy.”2 But with all 55 Republicans backing Roberts, Democratic objections did not matter. Today, the dance between Roberts and Senate Democrats and Republicans seems so predictable that it now seems a given that there will be proclamations of neutrality by Supreme Court nominees and party line voting by Senators. Indeed, Senate Republicans blocked a vote on Obama Supreme Court pick Merrick Garland in 2016 so that (in the words of Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell) “the American people . -

Crain's Detroit Busi N Ess

10t5t2020 Printable CRAIN'S DETROIT BUSI N ESS You may not reproduce, display on a website, distribute, sell or republish this article or data, or the information contained therein, without prior written consent. This printout and/or PDF is for personal usage only and not for any promotional usage. @ Crain Communications lnc. october 04,2o2o 06:38 PM I UeOnreo 41 MINUTES AGO Whitmer's COVID executive orders are out. Here are the pandemic restrictions still in. CHAD LIVENGOOD tr [ " Multiple legal avenues available to continue restrictions on business activity " None are nearly as broad and sweeping as a governor's executive orders " Counties are issuing orders after state Supreme Court ruled against Whitmer Chad Livengood/Craln's Detroit Businoss Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's executive order requiring customers and workers to wear masks inside indoor businesses is no longer enforceable after the Michigan Supreme Court struck down the law she used to impose the order, Attorney General Dana Nessel said Sunday. Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel announced Sunday that she will not enforce any of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's pandemic executive orders after the Michigan Supreme Court narrowly ruled that the governor has exceeded her authority for the past five months in managing the coronavirus pandemic. But that doesn't mean all government rules and regulations aimed at mitigating the spread of the airborne virus have gone away for businesses, schools and individuals. From the state public health code to business licensing and local health orders, there are multiple legal avenues for continued restrictions on business activity, though none nearly as broad and sweeping as a governor's executive orders. -

2019 It's All a Game: Top Trial Lawyers Tackle Evidence Friday

2019 It’s All A Game: Top Trial Lawyers Tackle Evidence 19-04 Friday, February 15, 2019 presented by The South Carolina Bar Continuing Legal Education Division http://www.scbar.org/CLE SC Supreme Court Commission on CLE Course No. 191498 1 Table of Contents Agenda ...................................................................................................................................................3 Speaker Biographies .............................................................................................................................4 Thinking Through the Structure of Evidence ....................................................................................7 Honorable John C. Few I See Dead People: Evidentiary Issues When Witnesses Die (or Disappear) Before Trial .............13 Christopher J. Bryant But It Happens All the Time; the Admissibility (or Not) of Other Similar Incidents ....................67 Julie L. Moore Expert Testimony, Will We Ever Settle Its Admissibility? Yes—Today!........................................76 Byron E. Gipson Rules of Evidence from L’Affaire Russe .............................................................................................82 Christopher P. Kenney The Ethics of Presenting (and Objecting to) Evidence ......................................................................134 Andrew B. Moorman SC Bar-CLE publications and oral programs are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered and are designed to help attorneys maintain