Youth Opioid Response (YOR) Team Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Streams and Watersheds of East Marin

Ch ile no t å V S 29 al å le y Rd I D St d Major Streams and WatershedsR of East Marin San Anto o ni i o n R o d t 9å3 S n an A A å nton io Rd n a S Ma rs ha d ll R P s e e ta y lum e a R R d t L P a a k m e lu vi ta lle Pe R d W i lso n H ill Rd SOULAJULE RESERVOIR L 4 a 2 k e v il North Novato le R d 9 48 7 6 3 ay w 0 gh 1 i H e at St r an Ma in S 3 D 7 N r ova U to n B i lv t d 7å3 e å å n d 77 L å S s d t a n v l o t e B m s STAFFORD LAKE d m H i o S o i g A w h th N d w e o e r East Marin Schools v a to a R n to y A d å Bå 55 1 v R lv t G e å d å ra 0 å Blackpoint e n å å å 63 å S t 59 a A 1 1, ADALINE E KENT MIDDLE SCHOOL 34, LYNWOOD ELEM. SCHOOL 67, RING MOUNTAIN DAY SCHOOL å v ve å r m A h D u t r l 7 D o a n å e L b t o 32 ong r å å e å s å Av a il e 2, ALLAIRE SCHOOL 35, MADRONE CONTINUATION HIGH SCHOOLP 68, ROSS ELEM. -

The Status of Career Technical Education in Marin County

2018–2019 MARIN COUNTY CIVIL GRAND JURY The Status of Career Technical Education in Marin County Report Date: June 20, 2019 Public Release Date: June 27, 2019 Marin County Civil Grand Jury The Status of Career Technical Education in Marin County SUMMARY In affluent Marin County there is an expectation on the part of parents that their children will attend and graduate from college. Schools have mirrored the expectations of parents and have stressed the importance of higher education for all students. This focus does not serve the interests of a substantial number of students who will complete their formal education with graduation from high school or who will not ultimately attain a college degree. The Marin County Civil Grand Jury understands that schools in the county have a two-fold mission: prepare students to succeed in post-secondary education (two- and four-year college degrees or formal certificate programs) or train them to go directly into the workforce. Vocational training, now included in what is called Career Technical Education (CTE), is not promoted sufficiently to accommodate those students who could benefit from such programs. Although the educational establishment in Marin County has increased opportunities for this group, the workforce bound group may be unaware of the programs that exist. More can be done. Currently, school counselors often focus on college choices and admissions. Our students would be better served if some of this valuable time was used in guiding students towards CTE offerings when appropriate. Similarly, career programs now center on vocations requiring extensive education — doctors, lawyers, engineers. Much more focus could be placed on CTE pathways — medical assisting, plumbing, auto repair. -

Sit O SAN RAFAEL CITY SCHOOLS June 27, 2019 the Honorable

Sit o SAN RAFAEL CITY SCHOOLS OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT MICHAEL WATENPAUGH, ED.D. 310 NOVA ALBION WAY, SAN RAFAEL, CA 94903 VANWSMS,Cfg June 27, 2019 The Honorable Judge Paul Haakenson Pat Randolph, Foreperson Mahn County Superior Court Mahn County Civil Grand Jury P.O. Box 4988 3501 Civic Center Drive, Room #275 San Rafael, CA 94913-4988 San Rafael, CA 94903 Dear Judge Haakenson and Foreperson Randolph: The San Rafael City Schools (SRCS) Board of Education, together with Dr. Michael Watenpaugh, Superintendent, acknowledge the efforts of the Mahn County Civil Grand Jury for highlighting challenges with youth vaping in the greater Mahn community, outlined in its report dated May 9, 2019, titled "Vaping: An Under-the-Radar Epidemic." Attached please find the requested response to the recommendations (R1, R4) from the San Rafael City Schools Board. Thank you for your continued interest in and support of our public schools and the health and wellness of Mahn county's youth. Sincerely, Greg Knell Michael Watenpaugh, Ed.D. Board of Education President Superintendent San Rafael City Schools Board of Education: Greg Knell, President; Maika Llorens Gulati, Vice President; Linda Jackson; Rachel Kertz; Natu Tuatagaloa SAN RAFAEL SkiCITY SCHOOLS OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT MICHAEL WATENPALIGH, Ear). 310 NOVA ALBION WAY, SAN RAFAEL, CA 94903 www.sres.org RECOMMENDATION Ri: The County of Mann Department of Health and Human Services, the Mann County Office of Education, and all school districts should increase initiatives to provide students, parents, and the community with more information and support on vaping prevention and cessation. Initiatives should include digital and social media content, including materials for middle and high schools. -

North Coast Section

CROSS COUNTRY DIVISIONS 2007-08 BASED ON 2006-07 CBEDS ENROLLMENT – GRADES 9 - 12 Last updated 6/20/07 DIVISION I – 2,111 & ABOVE AMADOR VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL 2535 FOOTHILL HIGH SCHOOL 2328 PITTSBURG HIGH SCHOOL 2586 ANTIOCH HIGH SCHOOL 2701 FREEDOM HIGH SCHOOL 2134 SAN LEANDRO HIGH SCHOOL 2648 ARROYO HIGH SCHOOL 2112 GRANADA HIGH SCHOOL 2384 SAN RAMON VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL 2147 BERKELEY HIGH SCHOOL 3140 JAMES LOGAN HIGH SCHOOL 4069 CALIFORNIA HIGH SCHOOL 2602 LIBERTY HIGH SCHOOL 2311 CASTRO VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL 2861 MONTE VISTA HIGH SCHOOL 2631 COLLEGE PARK HIGH SCHOOL 2134 MT EDEN HIGH SCHOOL 2212 DEER VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL 3307 NEWARK MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL 2157 DIVISION II 1,651– 2,110 ALAMEDA HIGH SCHOOL 1925 LIVERMORE HIGH SCHOOL 2045 UKIAH HIGH SCHOOL 1952 AMERICAN HIGH SCHOOL 2034 MISSION SAN JOSE HIGH SCHOOL 2108 WASHINGTON HIGH SCHOOL 2077 CARONDELET HIGH SCHOOL 1696 MONTGOMERY HIGH SCHOOL 1919 CASA GRANDE HIGH SCHOOL 2005 MT DIABLO HIGH SCHOOL 1653 CLAYTON VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL 1892 PETALUMA HIGH SCHOOL 1699 DE LA SALLE HIGH SCHOOL 2044 RANCHO COTATE HIGH SCHOOL 1968 EUREKA HIGH SCHOOL 1602 SAN LORENZO HIGH SCHOOL 1725 HAYWARD HIGH SCHOOL 1843 SANTA ROSA HIGH SCHOOL 2029 IRVINGTON HIGH SCHOOL 2010 TENNYSON HIGH SCHOOL 1759 DIVISION III – 1,101 – 1,650 ACALANES HIGH SCHOOL 1375 EL CERRITO HIGH SCHOOL 1266 MIRAMONTE HIGH SCHOOL 1399 ALBANY HIGH SCHOOL 1261 ELSIE ALLEN HIGH SCHOOL 1319 NORTHGATE HIGH SCHOOL 1581 ALHAMBRA HIGH SCHOOL 1435 ENCINAL HIGH SCHOOL 1196 NOVATO HIGH SCHOOL 1263 ANALY HIGH SCHOOL 1364 EUREKA HIGH SCHOOL 1602 PINER HIGH SCHOOL 1359 BISHOP O'DOWD HIGH SCHOOL 1161 HERCULES HIGH SCHOOL 1187 REDWOOD HIGH SCHOOL 1519 CAMPOLINDO HIGH SCHOOL 1380 HERITAGE HIGH SCHOOL 1297* SONOMA VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL 1618 CONCORD HIGH SCHOOL 1589 JOHN F. -

2019 Camp Final Concert Program

See You Next Year !!! July 18 – 25, 2020 Only 342 Days Away!! Register Now for Camp 2020 (at 2019 Prices!!) For Information and Camp Attendance next 2019 Camp Final year please come see us at the 2020 Registration Desk or check our website at: Concert Program www.lahondamusiccamp.org July 20-27, 2019 Camp Final Concert Program Camper families will be emailed the link to download the 2019 Hayward La Honda Music Our stay at camp has been an amazing and Camp Concert Performances (Free Download!!) memorable experience thanks to the individual and collective efforts of the awesome YMCA Staff. We especially appreciate the kindness and hard work of our hosts: Carrie Herrera, Colby Wiley, Luke Eberhart, Jim Marshall, Joel Avila, Nick Erwin, Tony Marcelo, Nikki Molova, Yolanda Zepeda, Feliciana Lopez, Mirabelle, Juan Martinez, Alejandro Rodriguez, Luis Lopez, Ivan Lopez, Mike (aka Mikey), Ben, Isabel, Laura, Alan, Ivan Ortega, Josue, Jose Negrete, Jasmine Negrete, Juan Negrete Let your friends and family know that YMCA Camp Jones Gulch is a BEAUTIFUL & AMAZING PLACE to visit!! A MILLION THANKS to Scott Martin for the BRILLIANT redesign of our new website! Check it out at lahondamusiccamp.org or Lahondamusiccamp.com Special thanks to our amazing volunteer logistic staff for large equipment and instrument load in/out: Russell Bowerman, Daniel Marquis, Michael Keating, Christian Gerardo, Frank Casados. Thank you Julia Marquis for the fabulous 2019 Camp T-Shirt Design!! But most importantly, we would like to extend, with a thundering round of applause , our appreciation to YOU (!!!) the Parents and Families of our Campers for Choosing Hayward La Honda Music Camp! We had a fantastic year and look forward to seeing all our amazing campers return for our 59th season of Camp July 18 – 25, 2020 !! We Sincerely Hope You Enjoy the Concert!!! 2019 Concert Program Junior Concert Band Joe Murphy, director Achilles' Wrath Sean O'Loughlin Our Kingsland Spring Samuel R. -

Community Service Fund Application Form

County of Marin Community Service Fund Program Application Date September 25, 2017 Application Form Fiscal Year July 1, 2017 - June 30, 2018 Organization Information Full Legal Name: Marin Athletic Foundation Organization URL: www.marinathleticfoundation.org Mission/purpose of your organization: The mission of the Marin Athletic Foundation is to support Marin County High School athletic programs by focusing on the health, safety, and injury prevention of all student athletes. MAF has established new initiatives that provide students, faculty, and staff with assistance and resources to create a safer athletic experience for everyone. These initiatives include baseline concussion testing, safety equipment and athletic trainers. Grant Request Information Program/Project Name: Health, Safety and Injury Prevention Program Amount Requested Dollar: $10,000.00 Total Project Cost: $1,125,000.00 Description of the proposed project/program, including the proposed project's goal(s), and the nature of the costs in specific terms, i.e. materials, labor costs, etc. Specifics of how the requested County funds will be used. The purpose of the Health, Safety and Injury Prevention program is to ensure that EVERY high school student athlete in Marin County has access to equipment and personnel to ensure a safe athletic experience. Specifically, MAF provides funding to participating high schools, based on need, to purchase impact sensors for helmets ($75,000), soft shell gear ($154,400), baseline concussion testing ($50,000) and athletic trainers ($845,000). The goal is to level the playing field in regards to safety and injury prevention, so that no matter which high school in Marin a student may attend, they are assured the same level of safety. -

San Rafael High School Master Facilities Long-Range Plan and Stadium Project Final Environmental Impact Report

SAN RAFAEL HIGH SCHOOL MASTER FACILITIES LONG-RANGE PLAN AND STADIUM PROJECT FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NUMBER 2016082017 Prepared for San Rafael City Schools March 2017 Prepared by Amy Skewes-Cox, AICP SAN RAFAEL HIGH SCHOOL MASTER FACILITIES LONG-RANGE PLAN AND STADIUM PROJECT FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NUMBER 2016082017 Prepared for San Rafael City Schools March 2017 Prepared by Amy Skewes-Cox, AICP In conjunction with BASELINE ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTING ENVIRONMENTAL COLLABORATIVE INTERACTIVE RESOURCES LSA ASSOCIATES NATALIE MACRIS PARISI TRANSPORTATION CONSULTING TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 A. Purpose of the Final EIR .................................................................................................. 1 B. Environmental Review Process ....................................................................................... 1 C. Report Organization ......................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER II COMMENT LETTERS AND RESPONSES FOR THE DEIR ..................................................... 3 A. Federal, State, and Local Agency Comments ................................................................. 5 B. Public and Public Interest Group Comments ................................................................. 43 CHAPTER III DEIR TEXT CHANGES ....................................................................................................... -

Tamalpais Union High School District 2018-2019 Coaches' Handbook

TAMALPAIS UNION HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 2018-2019 COACHES’ HANDBOOK Marin County Athletic League http://www.mcalsports.org/ North Coast Section, CIF http://www.cifncs.org/ California Interscholastic Federation http://www.cifstate.org/ Tamalpais High School Athletic Director: Christina Amoroso Phone: 415-380-3532 Fax: 415-380-3566 E-mail: [email protected] Athletic Asst: Patty Parnow - 415-380-3597 Mascot: Red-tailed Hawks Web Site: www.tamhigh.org/athletics Tam Boosters: [email protected] Sir Francis Drake High School Athletic Director: Nate Severin Phone: 415-458-3445 Fax: 415-458-3479 E-mail: [email protected] Athletic Asst.: Tyler Peterson - 415-458-3424 Mascot: Pirates Web Site: www.drakeathletics.org Drake Fund Athletic Comm: [email protected] Redwood High School Athletic Director: Jessica Peisch, CAA Phone: 415-945-3619 Fax: 415-945-3640 E-mail: [email protected] Athletic Asst: Mollie Elton - 415-945-3688 Mascot: Giants Web site: www.redwood.org/athletics Redwood Benchwarmers: http://tamdistrict.org/RHS_Benchwarmers Tamalpais Union High School District Athletic Coordinator: Chris McCune Phone: 415-945-1022 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.tamdistrict.org/athletics TAMALPAIS UNION HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT ATHLETICS ___________________________ High School 2018-19 COACHES’ HANDBOOK ACKNOWLEDGEMENT FORM Please print page, sign and turn in to your Athletic Director prior to the start of your season of sport. I have read the TUHSD Coaches’ Handbook and understand the contents. I know the Coaches’ Handbook represents the CIF, NCS, MCAL and TUHSD’s philosophy and rules on inter-scholastic athletics. I know that if I have any questions, my school’s Athletic Director or the District Athletic Coordinator, Chris McCune ([email protected]) are available to answer questions. -

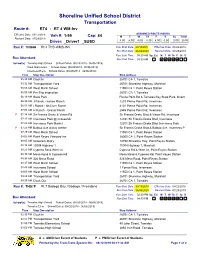

Remote Desktop Redirected Printer

Shoreline Unified School District Transportation Route #: RT4 - RT 4 WM-Inv Effective Date: 03/12/2018 ASSIGNED ROUTE HOURS Veh #: 1-99 Cap: 84 MTWThFSSuTotal Revised Date: 07/29/2019 Driver: _Driver1 _SUSD 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 0.00 0.00 20.00 Run #: THS4A Rt 4 THS-WMS-INV Run Start Date: 08/19/2019 Effective Date: 08/22/2018 Run End Date: 06/04/2020 Revised Date: 07/25/2019 Run Start Time: 05:30 AM Sp. Ed. MTWThFStS Bus Attendant: Run End Time: 09:30 AM School(s): Tomales High School School Dates: (08/20/2018 - 06/06/2019) West Marin Elem School Dates: (08/20/2018 - 06/06/2019) Inverness Elem School Dates: (08/20/2018 - 06/06/2019) Time Stop Description Stop Address 05:30 AM Clock In 26701 CA 1, Tomales 05:32 AM Transportation Yard 26701 Shoreline Highway, Marshall 05:56 AM West Marin School 11550 Ca 1, Point Reyes Station 06:00 AM Pre-Trip Inspection 26701 CA 1, Tomales 06:19 AM State Park Pierce Point Rd & Tomales Bay State Park, Invern 06:30 AM J Ranch - Kehoe Ranch 1210 Pierce Point Rd, Inverness 06:53 AM I Ranch - McClure Ranch 4101 Pierce Point Rd, Inverness 07:03 AM H Ranch - Grossi Ranch 2545 Pierce Point Rd, Inverness P 07:14 AM Sir Francis Drake & Vision Rd Sir Francis Drake Blvd & Vision Rd, Inverness 07:17 AM Inverness Park @ Crosswalk 12781 Sir Francis Drake Blvd, Inverness 07:23 AM Inverness Park Market 12301 Sir Francis Drake Blvd, Inverness Park P 07:25 AM Balboa Ave at bus shelter Sir Francis Drake Blvd & Balboa Ave, Inverness P 07:29 AM West Marin School 11550 Ca 1, Point Reyes Station 08:02 AM Point Reyes Vineyard -

Inverness to Iraq, and Back Record Have Been Worrying Fisheries Biolo- Gists up and Down the California Coast

MaRIN’S PuLITzER PRIzE-Winning NewspaPER $1.00 POINT REYES LIGHT Volume LX No. 49/ Point Reyes Station, California February 7, 2008 ELECTIONS > West Marin BUSINESS > Fairfax garage ECOLOGY > Marine Life CALENDAR > A soprano cast votes for Obama, McCain, becomes Good Earth Natural Protection Act spurs debate for from Fairfax joins female septet on in a high turn-out. /9 Food’s new parking lot. /10 fishermen, environmentalists./10 Saturday in San Geronimo. /20 County says no new permits in watershed by Jacoba Charles A two-year moratorium on building permits within Stream Conservation Areas (SCAs) in the San Geronimo Val- ley will be voted on by the Marin County Board of Supervisors on February 12. A Salmonid Habitat Enhancement Plan will be developed during that time, to provide guidelines for the county’s policies and actions in San Geronimo Val- ley SCAs. The plan and moratorium will affect properties along the 3.5-mile-long stretch of Lagunitas Creek between the Inkwells and the crest of White’s Hill. SPAWN had made it clear that with- out drastic action – such as developing Please turn to page 13 Where have the An American flag hangs at the Inverness home of Caleb Davis, who returned last month after two tours in Afghanistan and one tour in Iraq. Photo by Justin Nobel. salmon gone? by Jacoba Charles HABLANDO /4 Some of the lowest coho salmon runs on Inverness to Iraq, and back record have been worrying fisheries biolo- gists up and down the California coast. Red- How did the Latinos I always knew that I wanted to be in the by Justin Nobel wood Creek in West Marin had zero fish re- army, said Davis. -

2016 Marin County Community Health Needs Assessment

Healthy Marin Partnership Healthy Marin Partnership Pathways to Progress 2016 2016 Marin County Community Health Needs Assessment HMP Summary Report Acknowledgements This report would not be possible without the assistance of the HMP CHNA Coordination Team, Harder+Company Community Research (Harder+Company), the Healthy Marin Partnership leadership group, and subject matter experts who reviewed the report for accuracy. The HMP CHNA Coordination Team worked tirelessly with our contractor, Harder+Company on the content and context for this report. We are grateful for their ongoing contributions toward producing a high quality report. We would like to thank Harder+Company for excellent facilitation, data gathering and report writing. In addition, we are grateful for the input from local subject matter experts who reviewed the report data for accuracy and data quality. Introduction Healthy Marin Partnership (HMP) is committed to strengthening the health of Marin County. HMP recognizes the importance of taking a comprehensive view to understanding community health needs, and the critical advantage of working collaboratively to address these needs and advance health equity. This report provides a summary of the 2016 Community Health Needs Assessment results, which are intended to guide the work of Healthy Marin Partnership and our partners over the next three years and serve as a foundation to inform community action to address priority health needs. Background about HMP Healthy Marin Partnership (HMP) was formed in 1995 in response to a mandate requiring all not-for-profit hospitals to complete an assessment of our community every three years. In Marin, all of the hospitals joined together along with the United Way and Marin County Health and Human Services to do one assessment. -

Case Number 2011081106 Modified Document for Accessibility

BEFORE THE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS STATE OF CALIFORNIA In the Matter of: PARENT ON BEHALF OF STUDENT, OAH CASE NO. 2011081106 v. MARIN COUNTY MENTAL HEALTH YOUTH AND FAMILY SERVICES. DECISION Administrative Law Judge Deidre L. Johnson (ALJ), Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH), State of California, heard this matter on January 10, 2012, in Sacramento, California. Colleen A. Snyder, Attorney at Law, Ruderman & Knox LLP, represented Student and his Parent (Student).1 Neither Student nor his Mother was present during the hearing. Grandmother was present throughout the hearing on their behalf. No one appeared on behalf of Marin County Mental Health Youth and Family Services (CMHS).2 1 Christian Knox, Attorney at Law, was also present during the hearing. 2 Evidence established that the agency refers to itself as “Community Mental Health Services” (CMHS), or CMH. At the outset of the hearing, the ALJ requested OAH staff to call Marin County Deputy County Counsel Stephen R. Raab to see if he intended Accessibility modified document Student filed his request for a special education due process hearing (complaint) with OAH on August 26, 2011, naming both CMHS and the Novato Unified School District (District). On October 10, 2011, OAH granted a continuance of the case. On December 7, 2011, Student filed a notice of settlement and request for dismissal of the District from this case. On January 13, 2012, OAH dismissed the District from this action. At the hearing, oral and documentary evidence was received. Student delivered an oral argument at the close of the hearing, and the matter was submitted for decision.