American Symbol Returns from Obscurity: Boston's Liberty Tree by Smithsonian.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 08.26.16 Word Count 926 Level 1150L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The SAR Colorguardsman

The SAR Colorguardsman National Society, Sons of the American Revolution Vol. 5 No. 1 April 2016 Patriots Day Inside This Issue Commanders Message Reports from the Field - 11 Societies From the Vice-Commander Waxhaws and Machias Old Survivor of the Revolution Color Guard Commanders James Barham Jr Color Guard Events 2016 The SAR Colorguardsman Page 2 The purpose of this Commander’s Report Magazine is to o the National Color Guard members, my report for the half year starts provide in July 2015. My first act as Color Guard commander was at Point interesting TPleasant WVA. I had great time with the Color Guard from the near articles about the by states. My host for the 3 days was Steve Hart from WVA. Steve is from my Home town in Maryland. My second trip was to South Carolina to Kings Revolutionary War and Mountain. My host there was Mark Anthony we had members from North Car- information olina and South Carolina and from Georgia and Florida we had a great time at regarding the Kings Mountain. Went home for needed rest over 2000 miles on that trip. That activities of your chapter weekend was back in the car to VA and the Tomb of the Unknown. Went home to get with the MD Color Guard for a trip to Yorktown VA for Yorktown Day. and/or state color guards Went back home for events in MD for Nov. and Dec. Back to VA for the Battle of Great Bridge VA. In January I was back to SC for the Battle of Cowpens - again had a good time in SC. -

Colonial Flags 1775-1781

THE AMERICAN FLAG IS BORN American Heritage Information Library and Museum about A Revolutionary Experience GRAND UNION BETSY ROSS The first flag of the colonists to have any During the Revolutionary War, several patriots made resemblance to the present Stars and Stripes. It was flags for our new Nation. Among them were Cornelia first flown by ships of the Colonial Fleet on the Bridges, Elizabeth (Betsy) Ross, and Rebecca Young, all Delaware River. On December 3, 1775 it was raised of Pennsylvania, and John Shaw of Annapolis, Maryland. aboard Capt. Esek Hopkin's flagship Alfred by John Although Betsy Ross, the best known of these persons, Paul Jones, then a navy lieutenant. Later the flag was made flags for 50 years, there is no proof that she raised on the liberty pole at Prospect Hill, which was made the first Stars and Stripes. It is known she made near George Washington's headquarters in flags for the Pennsylvania Navy in 1777. The flag Cambridge, MA. It was the unofficial national flag on popularly known as the "Betsy Ross Flag", which July 4, 1776, Independence Day; and it remained the arranged the stars in a circle, did not appear until the unofficial national flag and ensign of the Navy until early 1790's. June 14, 1777 when the Continental Congress Provided as a Public Service authorized the Stars and Stripes. for over 115 Years COLONIAL THIRD MOUNTAIN REGIMENT The necessity of a common national flag had not been thought of until the appointment of a committee composed of Benjamin Franklin, Messrs. -

77 No 4 July-August. 1982

77 NO 4 JULY-AUGUST. 1982 C J‘N-fm'Ay LIBERTY July1August, 1982 •ITHE•TOLERANCE•GAMEIN • - - --y --„st • "I Will Tomorrow Not at School Be" • - • - --==r - - BY ELFRIEDE VOLK How I dreaded hearing else about going to a new school—having Taking a deep breath, I blurted, "I will the teachers and students find out that I was every Saturday away be. I go to—to church my Canadian teacher's different, that I was "strange." As a at Saturday." displaced person following the war, I had I clenched my teeth, dreading what might response! been through the humiliation several times come. I thought of Hugo Schwarz, a friend sat on the sunlit steps of the one-room already. My family had moved from Ger- in Germany, who spent every weekend in country school, trying to pay attention many to Czechoslovakia, to Poland, to jail because he refused to let his children to Gary, a grade-six student, reading Sweden, to Holland, and finally to Canada. attend school on Saturday, which he consid- 1from Dick and Jane. But Gary's voice And here I was, in my sixth country, and I ered to be God's holy Sabbath. Young as I kept drifting out of my consciousness; I was only 10 years old. was, I knew that every country had its own was wrestling with a problem far greater than I remembered the last school I had laws. What would be the Canadian posi- the complexities of learning a new language. attended in Holland, where a delegation of tion? It was Friday afternoon, and I knew that students had demanded why I had special The teacher tilted up my chin and smiled today I would have to tell my teacher. -

Using and Analyzing Political Cartoons

USING AND ANALYZING POLITICAL CARTOONS EDUCATION OUTREACH THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION This packet of materials was developed by William Fetsko, Colonial Williamsburg Productions, Colonial Williamsburg. © 2001 by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia INTRODUCTION TO LESSONS Political cartoons, or satires, as they were referred to in the eighteenth century, have provided a visual means by which individuals could express their opinions. They have been used throughout history to engage viewers in a discussion about an event, issue, or individual. In addition, they have also become a valuable instructional resource. However, in order for cartoons to be used effectively in the classroom, students must understand how to interpret them. So often they are asked to view a cartoon and explain what is being depicted when they really don’t know how to proceed. With that in mind, the material that follows identifies the various elements cartoonists often incorporate into their work. Once these have been taught to the students, they will then be in a better position to interpret a cartoon. In addition, this package also contains a series of representative cartoons from the Colonial period. Descriptors for these are found in the Appendix. Finally, a number of suggestions are included for the various ways cartoons can be used for instructional purposes. When used properly, cartoons can help meet many needs, and the skill of interpretation is something that has life-long application. 2 © C 2001 olonial  POLITICAL CARTOONS AN INTRODUCTION Cartoons differ in purpose, whether they seek to amuse, as does comic art; make life more bearable, as does the social cartoon; or bring order through governmental action, as does the successful political cartoon. -

Sons of Liberty

Sons of Liberty (Edited from Wikipedia) The Sons of Liberty was an organization of American colonists that was created in the Thirteen American Colonies. The secret society was formed to protect the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. They played a major role in most colonies in battling the Stamp Act in 1765. Although the group officially disbanded after the Stamp Act was repealed, the name was applied to other local Patriot groups during the years preceding the American Revolution. In the popular imagination, the Sons of Liberty was a formal underground organization with recognized members and leaders. More likely, the name was an underground term for any men resisting new Crown taxes and laws. The well-known label allowed organizers to issue anonymous summons to a Liberty Tree, "Liberty Pole," or other public meeting-place. Furthermore, a unifying name helped to promote inter-Colonial efforts against Parliament and the Crown's actions. Their motto became "No taxation without representation." History In 1765 the British government needed money to afford the 10,000 officers and soldiers stationed in the colonies, and intended that the colonists living there should contribute. The British passed a series of taxes aimed at the colonists, and many of the colonists refused to pay certain taxes; they argued that they should not be held accountable for taxes which were decided upon without any form of their consent through a representative. This became commonly known as "No Taxation without Representation." Parliament insisted on its right to rule the colonies despite the fact that the colonists had no representative in Parliament. -

I Spy Activity Sheet

Annaʻs Adventures I Spy Decipher the Cipher! You are a member of the Culper Ring, an espionage organization from the Revoutionary War. Practice your ciphering skills by decoding the inspiring words of a famous patriot. G Use these keys to decipher the code above. As you can see, the key is made up of two diagrams with letters inside. To decode the message, match the coded symbols above to the letters in the key. If the symbol has no dot, use the first letter in the key. If the symbol has a dot, use the second letter. A B C D E F S T G H I J K L Y Z U V W X M N O P Q R For example, look at the first symbol of the code. The highlighted portion of the key has the same shape as the first symbol. That shape has two letters in it, a “G” and an “H”. The first symbol in the code has no dot, so it must stand for the letter “G”. When you’re done decoding the message, try using the key to write messages of your own! Did You Know? Spying was a dangerous business! Nathan Hale, a spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolution, was executed by the British on September 22, 1776. It was then that he uttered his famous last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” © Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation • P.O. Box 1607, Williamsburg, VA 23187 June 2015 Annaʻs Adventures I Spy Un-Mask a Secret! A spy gave you the secret message below. -

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA District 1964-Present

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district 1964-2021 By Jonathan Belcher with thanks to Richard Barber and Thomas J. Humphrey Compilation of this data would not have been possible without the information and input provided by Mr. Barber and Mr. Humphrey. Sources of data used in compiling this information include public timetables, maps, newspaper articles, MBTA press releases, Department of Public Utilities records, and MBTA records. Thanks also to Tadd Anderson, Charles Bahne, Alan Castaline, George Chiasson, Bradley Clarke, Robert Hussey, Scott Moore, Edward Ramsdell, George Sanborn, David Sindel, James Teed, and George Zeiba for additional comments and information. Thomas J. Humphrey’s original 1974 research on the origin and development of the MBTA bus network is now available here and has been updated through August 2020: http://www.transithistory.org/roster/MBTABUSDEV.pdf August 29, 2021 Version Discussion of changes is broken down into seven sections: 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA 2) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Eastern Mass. St. Ry. Co. Norwood Area Quincy Area Lynn Area Melrose Area Lowell Area Lawrence Area Brockton Area 3) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Middlesex and Boston St. Ry. Co 4) MBTA bus routes inherited from Service Bus Lines and Brush Hill Transportation 5) MBTA bus routes initiated by the MBTA 1964-present ROLLSIGN 3 5b) Silver Line bus rapid transit service 6) Private carrier transit and commuter bus routes within or to the MBTA district 7) The Suburban Transportation (mini-bus) Program 8) Rail routes 4 ROLLSIGN Changes in MBTA Bus Routes 1964-present Section 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) succeeded the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) on August 3, 1964. -

Boston a Guide Book to the City and Vicinity

1928 Tufts College Library GIFT OF ALUMNI BOSTON A GUIDE BOOK TO THE CITY AND VICINITY BY EDWIN M. BACON REVISED BY LeROY PHILLIPS GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 328.1 (Cfte gtftengum ^regg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS . BOSTON • U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Introductory vii Brookline, Newton, and The Way about Town ... vii Wellesley 122 Watertown and Waltham . "123 1. Modern Boston i Milton, the Blue Hills, Historical Sketch i Quincy, and Dedham . 124 Boston Proper 2 Winthrop and Revere . 127 1. The Central District . 4 Chelsea and Everett ... 127 2. The North End .... 57 Somerville, Medford, and 3. The Charlestown District 68 Winchester 128 4. The West End 71 5. The Back Bay District . 78 III. Public Parks 130 6. The Park Square District Metropolitan System . 130 and the South End . loi Boston City System ... 132 7. The Outlying Districts . 103 IV. Day Trips from Boston . 134 East Boston 103 Lexington and Concord . 134 South Boston .... 103 Boston Harbor and Massa- Roxbury District ... 105 chusetts Bay 139 West Roxbury District 105 The North Shore 141 Dorchester District . 107 The South Shore 143 Brighton District. 107 Park District . Hyde 107 Motor Sight-Seeing Trips . 146 n. The Metropolitan Region 108 Important Points of Interest 147 Cambridge and Harvard . 108 Index 153 MAPS PAGE PAGE Back Bay District, Showing Copley Square and Vicinity . 86 Connections with Down-Town Cambridge in the Vicinity of Boston vii Harvard University ... -

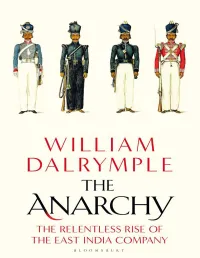

The Anarchy by the Same Author

THE ANARCHY BY THE SAME AUTHOR In Xanadu: A Quest City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India Begums, Thugs & White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857 Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 (with Yuthika Sharma) The Writer’s Eye The Historian’s Eye Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (with Anita Anand) Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company 1770–1857 Contents Maps Dramatis Personae Introduction 1. 1599 2. An Offer He Could Not Refuse 3. Sweeping With the Broom of Plunder 4. A Prince of Little Capacity 5. Bloodshed and Confusion 6. Racked by Famine 7. The Desolation of Delhi 8. The Impeachment of Warren Hastings 9. The Corpse of India Epilogue Glossary Notes Bibliography Image Credits Index A Note on the Author Plates Section A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred million people. Leo Tolstoy, letter to a Hindu, 14 December 1908 Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like. Edward, First Baron Thurlow (1731–1806), the Lord Chancellor during the impeachment of Warren Hastings Maps Dramatis Personae 1. THE BRITISH Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive 1725–74 East India Company accountant who rose through his remarkable military talents to be Governor of Bengal. -

MW Productions, 110 K Street, South Boston, MA 02127, 617-268-6700

Medicine Wheel breaks down barriers, breaks down barriers, whatever those barriers are, whether it’s violence, addiction, color, race, age, it doesn’t matter…… Martin J Walsh, Mayor of Boston January 29, 2018 Boston Planning and Development Agency 50 Liberty LLC One City Hall Plaza 9th Floor c/o The Fallon Company LLC Boston, MA 02210 One Marina Park Drive, Suite 1400 Attention Richard McGuinness Boston, MA 02210 Attention: Myrna Putziger Ladies and Gentlemen: The undersigned, being duly authorized to represent and act on behalf of Medicine Wheel Productions, Inc., and having reviewed and fully understood all of the requirements of that certain Request for Interest for Lease of 50 Liberty Civic/Cultural Space (“RFI”) and information provided therein, hereby submits the attached Application and supporting materials and applies for the opportunity to lease and activate the 50 Liberty Civic/Cultural Space. Capitalized terms used herein but not otherwise defined shall have the meanings ascribed to such terms in the RFI. The Developer, the BPDA and the DEP are hereby authorized by the Respondent to conduct any inquiries and investigations to verify the statements, documents, and information submitted in connection with this application, and to seek clarification from references and other third parties regarding the financial and operating capacity of the Respondent. If the Developer, the BPDA or the DEP have any questions regarding this Application, please contact the following individual: Michael Dowling Artistic Director Medicine Wheel Productions -

George Washington's Farewell

THE SAR COLORGUARDSMAN The National Society Sons of the American Revolution Volume 8 Number 4 January 2020 George Washington’s Farewell Xxxxx -1- In this Issue 10 4 Reports from the field National Color Guard Events - 2020 Dates and times are subject to change and interested parties should refer to the State society color guard activities from the last three months respective state society web sites closer to the actual event. 7 6 241st Anniversary of the Battle of George Washington Farewell Kettle Creek Table of Contents 10 Cannon Training Announcement Dr. Rudy Byrd, Artillery Commander Commander Report 3 Fifer’s Corner The Message from our Color Guard Commander 36 Color Guard Event Calendar 4 49 Grave Marking Ceremony Find the dates and locations of the many National Color Guard James Nalle events 5 Color Guard Commander Listing 50 250th Anniversary Flag Contact Information for all known State society color guard com- manders with reported changes 51 Adjutant’s Call 6 George Washinton’s Farewell If not us, who? If not now, when? 52 Safety Aricle Are you ready? 7 Kettle Creek Flyers page 9 Thomas Creek Fkyer -2- Commander’s Color Guard Adjutant Report Compatriots, Search It is time to begin the search for a new NSSAR Color Guard Adju- Un Hui and I hope all our SAR Colorguardsmen and their fami- tant lies enjoyed a wonderful Christmas AND that you have a healthy and prosperous 2020. On July 14, 2020 there will be a Change of Command for the Na- tional Society SAR Color Guard. The current Color Guard Command- I have been busy approving color guard awards: 22 Silver Color Guard Medals, 4 National Von Steuben Medals for Sustained Achieve- er will step down at the 130th Annual SAR Congress in Richmond, ment in the NSSAR Color Guard and 7 Molly Pitcher Medals. -

Sunday Liberty Pole

Sunday Liberty Pole Vol.2. No. 26; June 26, 2016 National: Publisher: San Fernando Valley Patriots http://thepatriotsalmanac.com Editor: Karen Kenney. Contributors: Duane “Bucky” Buckley (DB), Megan/Neuro7plastic (MN), Tom Adams (TA), Kyle Kyllan (KK), Aspen Pittman (AP), Dawn Wildman (DW), Maryanne Greenberg (MG), Carmen Otto (CO), Tom Zimmerman (TZ) Aborted Tissue used to Process Flavor Additives (News/Commentary); 6/18/2016 by Dave Hodges at The Common Sense Show: Abortion does leave a bad tasted. Got ‘Soylent Green’? http://www.thecommonsenseshow.com/2016/06/18/m ajor-food-corporations-use-tissue-aborted-babies- manufacture-flavor-additives-processed- foods/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_cam paign=major-food-corporations-use-tissue-aborted- babies-manufacture-flavor-additives-processed-foods Clinton's 'apology tour': Guns & Gays (News/Commentary) 6/16/2016 by Stephen Frank at California Political Review: Off target. http://www.capoliticalreview.com/capoliticalnewsandvi ews/democratclinton-problem-support-gays-or- apologize-for-terrorism/ When They Get the Guns, They will come for you (News/Commentary) 6/17/2016 Dave Hodges at The Common Sense Show: Again, what part of the 2A confuses Obama and the DHS? http://www.thecommonsenseshow.com/2016/06/17/w This “Liberty Pole” is one of hundreds erected in hen-they-come-for-your-guns-they-will-soon-come-for- America as a symbol of the colonials’ resistance to British tyranny. you/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campa The poles were often 100’ tall serving as places to meet or post political news. The Sons of Liberty erected the first one on May 21, ign=when-they-come-for-your-guns-they-will-soon- 1766 in Boston.