The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: a New Breeding Management Tool

Zoo Biology 35: 95–103 (2016) RESEARCH ARTICLE Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: A New Breeding Management Tool Kaitlin Croyle,1,2 Paul Gibbons,3 Christine Light,3 Eric Goode,3 Barbara Durrant,1 and Thomas Jensen1* 1San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Escondido, California 2Department of Biological Sciences, California State University San Marcos, San Marcos, California 3Turtle Conservancy, New York, New York Perivitelline membrane (PVM)-bound sperm detection has recently been incorporated into avian breeding programs to assess egg fertility, confirm successful copulation, and to evaluate male reproductive status and pair compatibility. Due to the similarities between avian and chelonian egg structure and development, and because fertility determination in chelonian eggs lacking embryonic growth is equally challenging, PVM-bound sperm detection may also be a promising tool for the reproductive management of turtles and tortoises. This study is the first to successfully demonstrate the use of PVM-bound sperm detection in chelonian eggs. Recovered membranes were stained with Hoechst 33342 and examined for sperm presence using fluorescence microscopy. Sperm were positively identified for up to 206 days post-oviposition, following storage, diapause, and/or incubation, in 52 opportunistically collected eggs representing 12 species. However, advanced microbial infection frequently hindered the ability to detect membrane-bound sperm. Fertile Centrochelys sulcata, Manouria emys,andStigmochelys pardalis eggs were used to evaluate the impact of incubation and storage on the ability to detect sperm. Storage at À20°C or in formalin were found to be the best methods for egg preservation prior to sperm detection. Additionally, sperm-derived mtDNA was isolated and PCR amplified from Astrochelys radiata, C. -

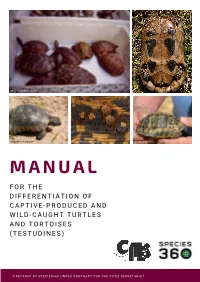

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

Abstracts from the 1999 Symposium

UTAH I THE I DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL ARIZONA NEVADA l I i I / + S v'LEI S % A|. w a CALIFORNIA PROCEEDINGS OF 1999 SYMPOSIUM DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL PROCEEDINGS OF THE 1999 SYMPOSIUM A compilation of reports and papers presented at the twenty-fourth annual symposium of the Desert Tortoise Council, March 5-8, 1999 St. George, Utah PUBLICATIONS OF THE DESERT TORTOISE COUNCIL, INC. Members Non-members Proceedings of the 1976 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1977 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1978 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1979 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1980 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1981 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1982 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1983 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1984 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1985 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1986 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1987-91 Desert Tortoise Council Symposia $20,00 $20.00 Proceedings of the 1992 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1993 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1994 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1995 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1996 Desert Tortoise Council Symposium $10.00 $15.00 Proceedings of the 1997-98 Desert Tortoise Council Symposia $10.00 $15.00 Annotated Bibliog raphy of the Desert Tortoise, Gopherus agassizii $10.00 $15.00 Note: Please add $1.00 per copy to cover postage and handling. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Serum Biochemical Parameters of Asian Tortoise (Agrionemys Horsfieldi)

International Journal of Veterinary Research Serum biochemical parameters of Asian tortoise (Agrionemys horsfieldi) Pourkabir, M.1 *; Rostami, A. 2 ; Mansour, H. 1 and Tohid-Kia, M.R.1 1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. 2Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Key Words: Abstract Asian tortoise; serum; biochemistry. At present, a great deal of attention is being focused on the tortoise as a domestic pet. Knowledge of the blood biochemical parameters in captivity Correspondence of this animal would be helpful for evaluations of their health. In this regard, Pourkabir, M., the serum biochemical values were measured in 12 Asian tortoises (6 males Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of and 6 females) before hibernation. Serum values of total protein (TOP) Tehran, P.O. Box: 14155-6453, Tehran, 63.19 ± 7.57 g/L, Albumin (Alb) 47.24 ± 10.66 g/L, creatinine (Crea) 57.4 ± Iran. 4.68 µmmol/L, glucose (Glc) 81.46 ± 21.88 mmol/L, urea 7.52 ± 2.74 Tel: +98(21) 61117147 mmol/L, uric acid (UA) 0.11 ± 0.028 mmol/L, aspartate transaminase Fax: +98(21) 66933222 (AST) 0.46 ± 0.017 µkal/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) 0.44 ± 0.053 Email: [email protected] µkal/L, amylase 1,157 ± 33.96 µkal/L, calcium (Ca) 2.74 ± 0.65 mmol/L, magnesium (Mg) 1.98 ± 0.24 mmol/L, and inorganic phosphorus (P) 1.26 ± Received 03 December 2009, 0.101 mmol/L were determined respectively. There were no significant Accepted 18 May 2010 differences in TOP, Alb, Glc, Crea, urea, UA, AST, ALT, amylase, Ca and P, and also Mg levels between males and females. -

A Sulcata Here, a Sulcata There, a Sulcata Everywhere Text and Photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter

A Sulcata Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) emerging from a burrow in its enclosure. of the African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) A Sulcata Here, A Sulcata There, A Sulcata Everywhere text and photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter n 1986 my wife and I fell in The breeder said to feed them pumpkin All the stucco along the side of the house love with the Sulcata Tor- and alfalfa. There was not a lot of diet infor- as far as they could ram was broken. The toise and decided to purchase mation available then. We did not have good male more than the female did the greater a pair. Yes, purchase. Twenty-three years luck with the breeder’s diet. They preferred damage. Our youngest son had the outside ago there were not many Sulcatas available. the Bermuda grass, rose petals and hibis- corner bedroom upstairs, every night after We found a “BREEDER” in Riverside, CA. cus flowers in the back yard. We gave them he would go to bed I could here him holler- Made the contact and brought the pair home other treats once in a while: apples, squash, ing at that %#@* turtle. The Sulcata would toI Ventura, CA. So began an adventure that and other vegetables. Pumpkin never was start ramming the side of the house. I would we still enjoy today. high on their list of treats! They also loved to go down and move him, put things in his We were told they were about seven years drink from a running hose laid on the lawn. -

Movement, Home Range and Habitat Use in Leopard Tortoises (Stigmochelys Pardalis) on Commercial

Movement, home range and habitat use in leopard tortoises (Stigmochelys pardalis) on commercial farmland in the semi-arid Karoo. Martyn Drabik-Hamshare Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Discipline of Ecological Sciences School of Life Sciences College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Campus 2016 ii ABSTRACT Given the ever-increasing demand for resources due to an increasing human population, vast ranges of natural areas have undergone land use change, either due to urbanisation or production and exploitation of resources. In the semi-arid Karoo of southern Africa, natural lands have been converted to private commercial farmland, reducing habitat available for wildlife. Furthermore, conversion of land to energy production is increasing, with areas affected by the introduction of wind energy, solar energy, or hydraulic fracturing. Such widespread changes affects a wide range of animal and plant communities. Southern Africa hosts the highest diversity of tortoises (Family: Testudinidae), with up to 18 species present in sub-Saharan Africa, and 13 species within the borders of South Africa alone. Diversity culminates in the Karoo, whereby up to five species occur. Tortoises throughout the world are undergoing a crisis, with at least 80 % of the world’s species listed at ‘Vulnerable’ or above. Given the importance of many tortoise species to their environments and ecosystems— tortoises are important seed dispersers, whilst some species produce burrows used by numerous other taxa—comparatively little is known about certain aspects relating to their ecology: for example spatial ecology, habitat use and activity patterns. -

A Survey of the Potential Distribution of the Threatened Tortoise Centrochelys Sulcata Populations in Burkina Faso (West Africa)

Tropical Ecology 57(4): 709-716, 2016 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com A survey of the potential distribution of the threatened tortoise Centrochelys sulcata populations in Burkina Faso (West Africa) FABIO PETROZZI1,2, EMMANUEL M. HEMA3,4 , LUCA LUISELLI1,5*& WENDENGOUDI GUENDA3 1Niger Delta Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation Unit, Department of Applied and Environmental Biology, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, P.M.B. 5080 Nkpolu, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria 2Ecologia Applicata Italia s.r.l., via Edoardo Jenner 70, Rome, Italy 3Université de Ouagadougou/CUPD, Laboratoire de Biologie et Ecologie Animales, 09 B.P. 848 Ouagadougou 09 - Burkina Faso 4Groupe des Expert en Gestion des Eléphants et de la Biodiversité de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (GEGEBAO) 5Institute for Development, Ecology, Conservation and Cooperation, via G. Tomasi di Lampedusa 33, I-00144 Rome, Italy Abstract: The African spurred tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata) is a threatened species, especially in West Africa, where it shows a scattered distribution. In Burkina Faso, the species distribution is unknown and we documented the current distribution and potential habitat characteristics. We found evidence of the species in a few sites in the northern and eastern part of the country, whereas some records from the southern part of Burkina Faso were considered unreliable. Multiple specimens were recorded only in four localities, mainly in the Sahel ecological zone. Annual rainfall was negatively related to the observed number of tortoises per site, and indeed these tortoises were found in the Sahel and adjacent ecoregions where rainfall is lower than other regions in Burkina Faso whereas latitude and numbers of tortoise individuals observed in each site were positively related. -

Russian Tortoise (Testudo Horsfieldii) Care Compiled by Dayna Willems, DVM

Russian Tortoise (Testudo horsfieldii) Care Compiled by Dayna Willems, DVM Brief Description The Russian Tortoise is a popular pet due to its small size and interactive personality. Native to central Asia, almost all available Russian Tortoises are wild caught as young adults (10-20 years old) and then imported for sale in the US. Unfortunately after being taken from the wild tortoises often have trouble adapting to captivity and die premature deaths from inadequate care. When scared tortoises will withdraw their body into their shell and their armored front legs will protect their head. The shell is living tissue and should never be pierced or painted. Adult size is 6-10" on average. Sexing The males will have longer tails the females and once mature the plastron (bottom part of the shell) will be concave and a longer, more pointed tail with a longer distance between vent and tail tip than the stubby tail of females where the vent is closer to the shell. Lifespan With proper care the average expected lifespan is 40-80 years on average. Caging Tortoises need large enclosures and should be in a 40 gallon tank or larger. An outdoor enclosure safe from predators or escape attempts is very beneficial when weather permits. Large containers such as Rubbermaid storage boxes or livestock troughs can also be used for enclosures successfully and inexpensively. There should be one or two things for your tortoise to hide under - half log, half buried clay pot, etc. Outdoor pens will need to be secure to keep tortoises in and predators (especially dogs) out. -

Federal Register/Vol. 66, No. 137/Tuesday, July 17, 2001/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 137 / Tuesday, July 17, 2001 / Rules and Regulations 37125 of this section, the scope of the by providing that only an accredited veterinarian and found free of ticks. reopened proceeding shall be limited to veterinarian may sign the certificate. This action was necessary to enable the a determination of the alien’s eligibility This action is necessary to enable the export, interstate commerce, health care, for suspension of deportation or export, interstate commerce, health care, and adoption of these types of tortoises cancellation of removal pursuant to and adoption of these types of tortoises while providing protection against the section 309(h)(1) of IIRIRA, as amended while providing protection against the spread of exotic ticks known to be by section 1505(c) of the LIFE Act spread of exotic ticks known to be vectors of heartwater disease. Amendments. vectors of heartwater disease. This We solicited comments on our second (3) If the Board has jurisdiction and action will also relieve an unnecessary interim rule for 60 days, ending grants only the motion to reopen filed burden on Federal veterinarians. September 19, 2000. We received two pursuant to paragraph (f) of this section, EFFECTIVE DATE: July 17, 2001. comments by that date. They were from a State department of agriculture and an it shall remand the case to the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Dr. Immigration Court solely for D. D. Wilson, Senior Staff Entomologist, association. We discuss the comments adjudication of the application for Emergency Programs, VS, APHIS, 4700 we received on the second interim rule, as well as comments we received on the suspension of deportation or River Road Unit 41, Riverdale, MD first interim rule that were not cancellation of removal pursuant to 20737–1231; (301) 734–8073. -

Sulcata Or African Spurred Tortoise Husbandry & Diet Information

Care of the Sulcata or African Spurred Tortoise Husbandry & Diet Information Quick Facts about Geochelone sulcata Lifespan: average 50-80 years, up to 150 years Average weight: females 39 kg (85 lb); males up to 50 kg (110 lb) Shell length: Up to 0.8 m (2.5 ft) Natural History These “gentle giants” are found throughout the southern edge of the Sahara in Africa. Sulcata tortoises inhabit environments that include hot arid desert, scrublands, and savannah. These tortoises DO NOT hibernate. Reproduction Sulcata tortoises reach sexual maturity at approximately 5 years of age, when they reach 11-18 kg (25-40 lb). This species breeds very well in captivity. When breeding occurs, a female may lay up to 6 clutches a year and 15-20 egg clutches are deposited. Eggs should be kept in vermiculite at 30ºC (86ºF) at 70%-80% humidity, hatchlings arise after 85-100 days incubation. Enclosure We strongly advise ADULTS BE HOUSED OUTSIDE for their health and due to their sheer size. Outdoor housing: Outdoor enclosures provided during warm weather months should be protected from predators and heavily planted with small ornamental scrubs and trees. Enclosures should also include rocky hiding places as well as additional shade areas. The Sulcata tortoise is a “true-burrowing” species, so it is essential to secure their outdoor environment as this strong species can EASILY tunnel and escape enclosures. Secure fencing is vital. The temperature range at all times should be 27-29ºC (80-85ºF) in the daytime with a basking site at 32-35ºC (90-95ºF). At night, temperature should drop below approximately 24ºC (75ºF). -

15Th Annual Symposium on the Conservation and Biology of Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles

CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA 2017 15th Annual Symposium on the Conservation and Biology of Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles Joint Annual Meeting of the Turtle Survival Alliance and IUCN Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group Program and Abstracts August 7 - 9 2017 Charleston, SC Additional Conference Support Provided by: Kristin Berry, Herpetologiccal Review, John Iverson, Robert Krause,George Meyer, David Shapiro, Anders Rhodin, Brett and Nancy Stearns, and Reid Taylor Funding for the 2016 Behler Turtle Conservation Award Provided by: Brett and Nancy Stearns, Chelonian Research Foundation, Deb Behler, George Meyer, IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Leigh Ann and Matt Frankel and the Turtle Survival Alliance TSA PROJECTS TURTLE SURVIVAL ALLIANCE 2017 Conference Highlights In October 2016, the TSA opened the Keynote: Russell Mittermeier Tortoise Conservation Center in southern Madagascar that will provide long- Priorities and Opportunities in Biodiversity Conservation term care for the burgeoning number of tortoises seized from the illegal trade. Russell A. Mittermeier is The TSA manages over 7,800 Radiated Executive Vice Chair at Con- Tortoises in seven rescue facilities. servation International. He served as President of Conser- vation International from 1989 to 2014. Named a “Hero for the Planet” by TIME magazine, Mittermeier is regarded as a world leader in the field of biodiversity and tropical forest conservation. Trained as a primatologist and herpetologist, he has traveled widely in over 160 countries on seven continents, and has conducted field work in more than 30 − focusing particularly on Amazonia (especially Brazil The TSA-Myanmar team and our vet- and Suriname), the Atlantic forest region of Brazil, and Madagascar.