An Investigation Into the Trade in Tortoises in Great Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English and French Cop17 Inf

Original language: English and French CoP17 Inf. 36 (English and French only / Únicamente en inglés y francés / Seulement en anglais et français) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING MADAGASCAR’S PLOUGHSHARE / ANGONOKA TORTOISE 1. This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Turtle Survival Alliance, and The Turtle Conservancy, in relation to agenda item 73 on Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.)*. 2. This species is restricted to a limited range in northwestern Madagascar. It has been included in CITES Appendix I since 1975 and has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species since 2008. There has been a significant increase in the level of illegal collection and trafficking of this species to supply the high end pet trade over the last 5 years. 3. Attached please find the joint statement regarding Madagascar’s Ploughshare/Angonoka Tortoise, which is considered directly relevant to Document CoP17 Doc. 73 on tortoises and freshwater turtles. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

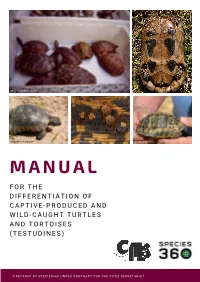

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Current Trends in the Husbandry and Veterinary Care of Tortoises Siuna A

Current trends in the husbandry and veterinary care of tortoises Siuna A. Reid BVMS CertAVP(ZooMed) MRCVS Presented to the BCG symposium at the Open University, Milton Keynes on 25th March 2017 Introduction Tortoises have been kept as pets for centuries but have recently gained even more popularity now that there has been an increase in the number of domestically bred tortoises. During the 1970s there was the beginning of a movement to change the law and also the birth of the British Chelonia Group. A small group of forward thinking reptile keepers and vets began to realise that more had to be done to care for and treat this group of pets. They also recognized the drawbacks of the legislation in place under the Department of the Environment, restricting the numbers of tortoises being imported to 100,000 per annum and a minimum shell length of 4 inches (10.2cm). Almost all tortoises were wild caught and husbandry and hibernation meant surviving through the summer in preparation for five to six months of hibernation. With the gradual decline in wild caught tortoises, this article compares the husbandry and veterinary practice then with today’s very different husbandry methods and the problems that these entail. Importation Tortoises have been imported for hundreds of years. The archives of the BCG have been used to loosely sum up the history of tortoise keeping in the UK. R A tortoise was bought for 2s/6d from a sailor in 1740 (Chatfield 1986) R Records show as early as the 1890s tortoises were regularly being brought to the UK R In 1951 250 surplus tortoises were found dumped in a street in London –an application for a ban was refused R In 1952 200,000 tortoises were imported R In 1978 the RSPCA prosecuted a Japanese restaurant for cooking a tortoise – boiled alive (Vodden 1983) R In 1984 a ban on importation of Mediterranean tortoises was finally approved 58 © British Chelonia Group + Siuna A. -

Chelonoidis Chathamensis)

Volume 6 • 2018 10.1093/conphys/coy004 Research article Biochemistry and hematology parameters of the San Cristóbal Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis chathamensis) Gregory A. Lewbart1,*, John A. Griffioen1, Alison Savo1, Juan Pablo Muñoz-Pérez2, Carlos Ortega3, Andrea Loyola3, Sarah Roberts1, George Schaaf1, David Steinberg4, Steven B. Osegueda2, Michael G. Levy1 and Diego Páez-Rosas2,3 1College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, 1060 William Moore Drive, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA 2Galápagos Science Center, University San Francisco de Quito, Av. Alsacio Northia, Isla San Cristobal, Galápagos, Ecuador 3Dirección Parque Nacional Galápagos, Galapagos, Ecuador 4Department of Biology, University of North Carolina, Coker Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA *Corresponding author: College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences, North Carolina State University, 1060 William Moore Drive, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA. Email: [email protected] .............................................................................................................................................................. As part of a planned introduction of captive Galapagos tortoises (Chelonoidis chathamensis) to the San Cristóbal highland farms, our veterinary team performed thorough physical examinations and health assessments of 32 tortoises. Blood sam- ples were collected for packed cell volume (PCV), total solids (TS), white blood cell count (WBC) differential, estimated WBC and a biochemistry panel including lactate. In some cases not all of the values were obtainable but most of the tortoises have full complements of results. Despite a small number of minor abnormalities this was a healthy group of mixed age and sex tortoises that had been maintained with appropriate husbandry. This work establishes part of a scientific and tech- nical database to provide qualitative and quantitative information when establishing sustainable development strategies aimed at the conservation of Galapagos tortoises. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Die Brutbiologie Der Strahlenschildkröte (Astrochelys Radiata , Shaw 1802) Unter Natürlichen Und Naturnahen Bedingungen in Südwestmadagaskar

Die Brutbiologie der Strahlenschildkröte (Astrochelys radiata , Shaw 1802) unter natürlichen und naturnahen Bedingungen in Südwestmadagaskar Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften des Fachbereichs Biologie, der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften, der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Jutta M. Hammer aus Helmstedt Hamburg, Dezember 2012 Für Susi und Klaus-Bärbel, die mir erste Eindrücke in gepanzertes Leben vermittelten Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Die Erfindung der Eier................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Die Brutbiologie der Schildkröten................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Landschildkröten auf Madagaskar................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Ziele dieser Untersuchung ............................................................................................................ 5 2. Material und Methoden...................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Untersuchungsgebiete und -zeitraum .......................................................................................... 6 2.2 Regionales Klima Südwestmadagaskar........................................................................................ -

Fatal Caeco-Colic Impaction in a Captive African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone Sulcata)

Global Veterinaria 15 (5): 466-468, 2015 ISSN 1992-6197 © IDOSI Publications, 2015 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.gv.2015.15.05.93243 Short Communication: Fatal Caeco-Colic Impaction in a Captive African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) 12M.O. Tijani, C.K. Ezeasor and 3T.K. Adebiyi 1Department of Veterinary Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria 2Department of Veterinary Pathology and Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Nigeria 3Veterinary Teaching Hospital, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Abstract: The carcass of a 26 year old African spurred tortoise with a history of anorexia of four days duration was presented for necropsy at the Department of Veterinary pathology, University of Ibadan. Necropsy revealed total obstruction of the caecum and proximal part of the colon with an entangled mass of polythene and cotton material, intestinal necrosis and haemorrhage, severe gastrointestinal congestion, pulmonary and hepatic congestion. Histopathology of the colon revealed severe diffuse necrosis and loss of epithelium, severe haemorrhage in the lamina propria, oedema of the submucosa and congestion of blood vessels in the lamina propria, submucosa and muscularis externa. There was severe congestion of the hepatic sinusoids. Although there have been several reports on the obstruction of the gastrointestinal tracts of captive tortoises with foreign materials such as gravel and corn cob; obstruction of the caecum and colon of African spurred tortoises with polythene and cotton material have not been reported. We hereby report a case of fatal caecum-colic impaction in a captive African spurred tortoise. Key words: African Spurred Tortoise Caecum Colon Impaction INTRODUCTION tortoise in Nigeria and this perhaps is the first report of caeco-colic impaction in the African spurred tortoise in Gastrointestinal obstructions are commonly seen Nigeria. -

A Sulcata Here, a Sulcata There, a Sulcata Everywhere Text and Photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter

A Sulcata Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) emerging from a burrow in its enclosure. of the African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) A Sulcata Here, A Sulcata There, A Sulcata Everywhere text and photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter n 1986 my wife and I fell in The breeder said to feed them pumpkin All the stucco along the side of the house love with the Sulcata Tor- and alfalfa. There was not a lot of diet infor- as far as they could ram was broken. The toise and decided to purchase mation available then. We did not have good male more than the female did the greater a pair. Yes, purchase. Twenty-three years luck with the breeder’s diet. They preferred damage. Our youngest son had the outside ago there were not many Sulcatas available. the Bermuda grass, rose petals and hibis- corner bedroom upstairs, every night after We found a “BREEDER” in Riverside, CA. cus flowers in the back yard. We gave them he would go to bed I could here him holler- Made the contact and brought the pair home other treats once in a while: apples, squash, ing at that %#@* turtle. The Sulcata would toI Ventura, CA. So began an adventure that and other vegetables. Pumpkin never was start ramming the side of the house. I would we still enjoy today. high on their list of treats! They also loved to go down and move him, put things in his We were told they were about seven years drink from a running hose laid on the lawn. -

A Survey of the Potential Distribution of the Threatened Tortoise Centrochelys Sulcata Populations in Burkina Faso (West Africa)

Tropical Ecology 57(4): 709-716, 2016 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com A survey of the potential distribution of the threatened tortoise Centrochelys sulcata populations in Burkina Faso (West Africa) FABIO PETROZZI1,2, EMMANUEL M. HEMA3,4 , LUCA LUISELLI1,5*& WENDENGOUDI GUENDA3 1Niger Delta Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation Unit, Department of Applied and Environmental Biology, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, P.M.B. 5080 Nkpolu, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria 2Ecologia Applicata Italia s.r.l., via Edoardo Jenner 70, Rome, Italy 3Université de Ouagadougou/CUPD, Laboratoire de Biologie et Ecologie Animales, 09 B.P. 848 Ouagadougou 09 - Burkina Faso 4Groupe des Expert en Gestion des Eléphants et de la Biodiversité de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (GEGEBAO) 5Institute for Development, Ecology, Conservation and Cooperation, via G. Tomasi di Lampedusa 33, I-00144 Rome, Italy Abstract: The African spurred tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata) is a threatened species, especially in West Africa, where it shows a scattered distribution. In Burkina Faso, the species distribution is unknown and we documented the current distribution and potential habitat characteristics. We found evidence of the species in a few sites in the northern and eastern part of the country, whereas some records from the southern part of Burkina Faso were considered unreliable. Multiple specimens were recorded only in four localities, mainly in the Sahel ecological zone. Annual rainfall was negatively related to the observed number of tortoises per site, and indeed these tortoises were found in the Sahel and adjacent ecoregions where rainfall is lower than other regions in Burkina Faso whereas latitude and numbers of tortoise individuals observed in each site were positively related. -

Homing in the Red-Eared Slider (Trachemys Scripta Elegans) in Illinois Authors: John K

Homing in the Red-Eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) in Illinois Authors: John K. Tucker, and James T. Lamer Source: Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 7(1) : 145-149 Published By: Chelonian Research Foundation and Turtle Conservancy URL: https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-0669.1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Chelonian-Conservation-and-Biology on 08 Sep 2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by United States Fish & Wildlife Service National Conservation Training Center NOTES AND FIELD REPORTS Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2008, 7(1): 88–95 Winokur (1968) could not determine the rate of hybrid- Ó 2008 Chelonian Research Foundation ization, concluded the identification of some specimens as hybrids to be uncertain, and verified pure A. atra. By 1979, The Status of Apalone atra Populations in Smith and Smith considered A.