Kenya's Gubernatorial Impeachments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenya General Elections, 2017

FINAL REPORT REPUBLIC OF KENYA General Elections 2017 REPUBLIC OF KENYA European Union Election Observation Mission FINAL REPORT General Elections 2017 January 2018 This report contains the findings of the EU Election Observation Mission (EOM) on the general elections 2017 in Kenya. The EU EOM is independent from the European Union’s institutions, and therefore this report is not an official position of the European Union. KEY CONCLUSIONS OF THE EU EOM KENYA 2017 1. The Kenyan people, including five million young people able to vote for the first time, showed eagerness to participate in shaping the future of their country. However, the electoral process was damaged by political leaders attacking independent institutions and by a lack of dialogue between the two sides, with escalating disputes and violence. Eventually the opposition withdrew its presidential candidate and refused to accept the legitimacy of the electoral process. Structural problems and specific electoral issues both need to be addressed meaningfully to prevent problems arising during future elections. 2. Electoral reform needs to be carried out well in advance of any election, and to be based on broad consensus. The very late legal amendments and appointment of the leadership of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) before the 2017 elections put excessive pressure on the new election administration. 3. Despite efforts to improve the situation, there was a persistent lack of trust in the IEBC by the opposition and other stakeholders, demonstrating the need for greater independence and accountability as well as for sustained communication and more meaningful stakeholder consultation. There was improved use of technology, but insufficient capacity or security testing. -

Mygov Issue 5 AUGUST 04, 2020

FOR FREE CIRCULATION www.mygov.go.ke August 4, 2020 The best prevention YOUR WEEKLY REVIEW against the coronavirus is still washing your hands and keeping safe social distance For FINAL Issue No. 5/2020-2021 +254 020 4920000 [email protected] Kenya to remove roadblocks The Week In numbers along the Northern Corridor NEC Main line Sh1.7b SOUTH SUDAN The cost of a floating NEC Branch line PS says inland Juba pedestrian bridge to be constructed at container the Liwatoni area of depots to be Mombasa Island. upgraded as well as KENYA 3,000 Tororo UGANDA Number of teachers constructing from private and Kampala educational facilities Kisumu refurbishing Nairobi in Nakuru in need of Kigali food of port and oil RWANDA pipelines to TANZANIA Bujumbura 552,000 promote trade BURUNDI Mombasa Kenyans living with Diabetes according BY BERNADETTE KHADULI/ to International HILARY MONGERA said Dr. Mwakima. Transport Coordination Au- Diabetes Federation thority Executive Commit- (IDF) data enya is set to remove tee was speaking during the all roadblocks along opening of the virtual meet- Kthe Northern Cor- ing. Kampala –Uganda. But since She said the involvement 612 ridor, as well as expand and In a press statement to the outbreak of coronavirus of the public sector can be Cases of child upgrade transport infra- newsrooms, Dr. Mwakima pandemic in the region and achieved if the countries for- labour that have structure in order to promote said Kenya also intends to containment measures put mulate policies, regulatory been captured by trade in the East African extend the Standard Gauge in place to curb COVID-19 and institutional frameworks Child Protection Community region. -

The 5Th Annual Devolution Conference 2018

The Devolution Experience 2 Table of Contents Message from the Chairman, Council of Governors 3 Message from the Vice Chairperson, COG and the Chair of the Devolution Conference Committee 4 Message from the Speaker of the Senate 6 Message from the Cabinet Secretary, Ministry of Devolution and ASAL 7 Message from the Chairman, County Assemblies Forum 9 Message from the County Government of Kakamega 10 Acknowledgement by the Chief Executive Officer, Council of Governors 11 Mombasa County 16 Kwale County 18 Kilifi County 20 Tana River County 22 Lamu County No content provided Taita-Taveta County 24 Garissa County 26 Wajir County 28 Mandera County 32 Marsabit County 34 Isiolo County 36 Meru County 38 Tharaka-Nithi County 40 Embu County No content provided Kitui County 42 Machakos County 44 Makueni County 48 Nyandarua County 50 Nyeri County 52 Kirinyaga County 54 The Devolution Experience 1 Murang’a County 56 Kiambu County 58 Turkana County 60 West Pokot County 62 Samburu County 66 Trans Nzoia County 68 Uasin Gishu County 70 Elgeyo-Marakwet County 72 Nandi County 74 Baringo County 76 Laikipia County 78 Nakuru County 80 Narok County 84 Kajiado County 86 Kericho County 88 Bomet County 90 Kakamega County 94 Vihiga County 96 Bungoma County 96 Busia County 100 Siaya County 104 Kisumu County 106 Homa Bay County 108 Migori County 110 Kisii County 112 Nyamira County 114 Nairobi County 116 Partners and Sponsors 119 2 The Devolution Experience MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN, COUNCIL OF GOVERNORS It has been eight years since the promulgation of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 which ushered a devolved system of governance that assured Kenyans of equitable share of resources and better service delivery for all. -

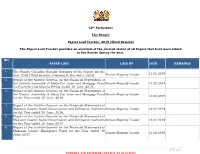

The Papers Laid Tracker Third Session As at December 5Th, 2019

12th Parliament The Senate Papers Laid Tracker, 2019 (Third Session) The Papers Laid Tracker provides an overview of the current status of all Papers that have been tabled in the Senate during the year. NO PAPER LAID LAID BY DATE REMARKS 1. The Senate Calendar Regular Sessions of the Senate for the 13.02.2019 Year 2019 (Third Session, February to December, 2019). Senate Majority Leader 2. Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statements of the County Assembly of Siaya Car Loan and Mortgage Fund Senate Majority Leader 13.02.2019 for Fourteen (14) Months Period ended 30 June, 2015. 3. Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statements of the County Assembly of Siaya Car Loan and Mortgage Fund Senate Majority Leader 13.02.2019 for the Year ended 30 June, 2016. 4. Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statements of Makueni County Sand Conservation and Utilization Authority Senate Majority Leader 13.02.2019 for the Year ended 30 June, 2016. 5. Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statements of Makueni County Sand Conservation and Utilization Authority Senate Majority Leader 13.02.2019 for the Year ended 30 June, 2017. 6. Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statements of Makueni County Emergency Fund for the Year ended 30 Senate Majority Leader 13.02.2019 June, 2017. 1 | P a g e PAPERS LAID TRACKER (STATUS AT 05.12.2019) 7. Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statements of the Makueni County Youth, Men, Women, Persons with Senate Majority Leader 13.02.2019 Disabilities and Table – Banking Groups Empowerment Fund for the Year ended 30 June, 2017. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.)

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXIX—No. 137 NAIROBI, 15th September, 2017 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 9060 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITIONS RULES, 2017 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 (3) of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2017, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the Judges and Magistrates listed and sitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE HIGH COURT No. Electoral Area Election Petition No. Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Election Court Court Station (Venue) GOVERNOR 1. Bom et County Kericho High Court Kiplagat Richard Sigei IEBC Justice Martin Bomet Election Petition No. 1 Elijah Koech Joyce Cherono Laboso Muya of 2017 Alvin K. Koech 2. Busi a County Busia High Court Peter Odima Khasamule IEBC Justice Kiarie Busia Election Petition No. 4 Returning Officer Busia County Waweru Kiarie of 2017 Fredrick Apopa Sospeter Odeke Ojaamong 3. Emb u County Embu High Court Lenny Maxwell Kivuti IEBC Justice William Embu ElectionPetition No.1 Embu County Returning Officer Musyoka of 2017 Martin Nyaga Wambora David Kariuki 4. Gari ssa County Garissa High Court Nathif Jama Adan Ali Buno Korane Justice James Nairobi ElectionPetition No.2 County Returning Officer Wakiaga of 2017 Antony Njoroge Douglas IEBC 5. -

WED PAGE 1 1110.Indd

WWW.THE-STAR.CO.KE INDEPENDENT VOICES /THESTARKENYA FRESH AND OKECH KENDO DIFFERENT @THESTARKENYA CHAIRMAN 11 CHEBUKATI’S OCTOBER 2017 POISONED WEDNESDAY e power of the lawyer is in CHALICE the uncertainty of the law KSh60 (TSh1,000, USh2,000) PAGE 18 Jeremy Bentham English philosopher DEMAMD NASA LEADER WANTS FRESH NOMINATIONS IN 90 DAYS, LEADING TO ANOTHER ELECTION Uncertainty as Raila withdraws from Oct 26 poll IEBC meets legal advisers to decide way forward. NASA says interim period should be used to reform electoral commission, President says rerun should go on as ordered by Supreme Court PG 4-5 NEWS NASA MPs say law amendments are dictatorial and dangerous PAGE 7 NEWS Mutula had seen his death coming, wife Nduku tells inquest PAGE 2 NEWS 3.4 million people face starvation due to drought, in need of urgent aid PAGE 13 PHYSICAL: Starehe MP Charles Njagua and Embakasi East MP Babu Owino fi ght Parliament yesterday. Njagua told Owino to respect the President /HEZRON NJOROGE 2 THE-STAR.CO.KE Wednesday, October 11, 2017 e late Senator NAIROBI ‘DERBY’ Mutula Kilonzo’s second wife Nduku testfi es in a Machakos Jaguar, Babu court yesterday /ANDREW MBUVA fi ght in House media centre RECEIVED LETTER WITH STRANGE POWDER Mutula had premonition MPs Charles Njagua and Babu Owino at Parliament’s media centre yesterday /HEZRON NJOROGE of his death — 2nd wife GIDEON KETER @ArapGKeter ‘Said his life was in danger after he saw some insects in his house’ Legislators Charles Njagua and Babu Owino fought at Parliament’s media centre yesterday, forcing sergeants- was about a threat he had received message to his phone. -

Download PDF (4.5

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXIX—No.137 NAIROBI, 15th September, 2017 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE No.9060 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITIONS RULES, 2017 IN EXERCISEof the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 (3) of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2017, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereundershall be heard in the election courts comprising of the Judges and Magistrates listed and sitting at the courtstations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE HIGH COURT No.) Electoral Area Election Petition No. Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Election Court Court Station (Venue) GOVERNOR 1. |Bomet County Kericho High Court Kiplagat Richard Sigei TEBC Justice Martin Bomet Election Petition No. 1] Elijah Koech Joyce Cherono Laboso Muya of 2017 Alvin K. Koech 2. Busia County Busia High Court Peter Odima Khasamule TEBC Justice Kiarie Busia Election Petition No. 4 Returning Officer Busia County Waweru Kiarie of 2017 Fredrick Apopa Sospeter Odeke Ojaamong 3. |Embu County Embu High Court Lenny Maxwell Kivuti TEBC Justice William Embu ElectionPetition No.1 Embu County Returning Officer Musyoka of 2017 Martin Nyaga Wambora David Kariuki 4. |Garissa County Garissa High Court Nathif Jama Adan Ali Buno Korane Justice James Nairobi ElectionPetition No.2 County Returning Officer Wakiaga of 2017 Antony Njoroge Douglas IEBC 5. |Homabay County Homabay High Court Joseph Oyugi Magwanga TEBC Justice J. -

The Countytrak Performance Index 2019/20

COUNTYTRAK PERFORMANCE INDEX THE COUNTYTRAK PERFORMANCE INDEX 2019/20 www.countytrak.infotrakresearch.com Introduction Kenyans overwhelmingly ushered in our current constitution on the promise of devolution which they felt result in increased grass root access to resources and political power. Indeed people’s expectations of county governments continue to be extremely high. While most county governments tend appreciate this fact and try to capitalise on low hanging fruits as soon as they kick off, others prefer to spend the nascent stages laying the ground work and planning elaborately for delivery. Irrespective of leadership styles may differ, what is critical is for people to feel the impact of devolution in their daily lives. County governments need to fully decipher the perceptions of their residents and develop strategies that are concomitant with their expectations. It’s against this back drop that Infotrak Research developed the CountyTrakTM Performance index to provide Citizens’ Scorecard of their County governments against set key performance indicators. The CountyTrak Methodology “The Index will be the first of its kind and magnitude in Kenya. It provides an excellent baseline from which other evaluation tools can be developed and more importantly provides the county governments and other interested stakeholders with robust statistics by ward on the perception of county residents over county governments’ performance of the devolved functions.” • Our current index was conducted between October–December 2019 and January 2020 covering all the 47 counties, 290 constituencies and 1450 wards with an overall sample of 37,600. Each county was treated as an individual universe and assigned a cluster sample which ranged between 600 and 2000 respondents guided by the population and number of wards in the respective counties. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) � Vol

C)11.\" Cl I, FOR VAATIOVVJ ,1, LA PI,VORT titlmt6 THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXII —No. 40 NAIROBI, 28th February, 2020 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTE NOTICES—(Contd.) PAGE PAGE The Employment and Labour Relations Court Act— The Physical and Land Use Planning Act—Completion of 1116 Appointment Development Plans, etc 1148 The Civil Procedure Act—Appointments 1116 The Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act— The Standards Act—Re-Appointment 1116 Environmental Impact Assessment Study Reports 1148-1156 The Kenya National Examinations Council Act Disposal of Uncollected Goods 1156-1157 —Re-Appointment, etc 1116-1117 Change of Names 1157-1159 The Mining Act—Appointments 1117-1120 The National Social Security Fund Act—Appointment 1121 The Central Bank of Kenya Act—Notification of SUPPLEMENT Nos. 9,10 and 11 Change of Name 1121 Legislative Supplements, 2020 The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional LEGAL NOTICE NO. PAGE Certificates, etc 1121-1134 The Land Act—Intention to Acquire 1134-1138 10 —The Industrial Training (Training Levy) (Amendment) Order, 2020 89 The East African Community Customs Management Act—Appointment of Transit Route 1138 11 —The Standards (Verification of Conformity to Standards and Other Applicable Regulations The High Court of Kenya—Easter Recess 1138 of Imports) (Amendment) Regulations, 2020 90 1138-1141 County Government Notices 12 —The Companies (Beneficial Ownership Information) The Insurance Act—Claims -

THE-PEOPLE-11.10.2018.Pdf

www.peopledaily.co.ke // www.epaper.peopledaily.co.ke 12 .HQ\D·V COMMENTARY )5(( 1HZVSDSHU Who will end this slaughter on our roads? Kenya's most horrendous road crash yesterday dawn in Fort Ternan, Kericho county which snuffed out a mind-boggling 50 lives came barely two weeks after a similar bus carnage near Gilgil where 12 perished. These statistics are numbing and the question must be asked; when will this dalliance with morbidity end? Research and trends are unequivocal that our road accidents are largely attributable to human error. The factors !&RQWLQXHGRQSDJH People Daily NO.06668 T h u r s d a y , O c t o b e r 11, 2 0 18 dawn plunge>>pages 4-8 NEWS BEAT Thursday, October 11, 2018 / PEOPLE DAILY Opinion World Business Sport We need a Pope likens Over 6,000 Stars hold referendum abortion flower farm Ethiopia to to address to ‘hiring workers keep Afcon POINTERS excesses a killer’ laid off dream alive P10Kenya has P16Pontiff says P17 High production P31 After draw, Kenya inordinately interrupting a cost, shrinking now leads Group high number of pregnancy same market, multiple F with four points, representatives, as eliminating taxes blamed for one ahead of Ghana argues columnist someone sub-sector’s woes and Ethiopia &KDRVDVFRSV HYLFWKDZNHUV DWFLW\PDUNHW 6OHXWKVKXQWIRU-RZLH E\.LQ\XUX0XQXKH #NLQ\XUXPXQXKH Chaos erupted at City Market in Nairobi yesterday as anti-riot police officers evicted hawkers operating at the facility illegally. ¶SDUWQHU·LQ0RPEDVD Traders who own stalls at the when he visited Monica’s apart- market had alerted police of a Suspect captured by CCTV ment off Dennis Pritt Road in Nai- looming face-off after hawk- cameras with Irungu on the robi’s Kilimani area. -

Makinika Kuhusu Afya Na Matibabu

Makinika kuhusu afya na matibabu A NATION MEDIA GROUP PUBLICATION ‘AFYA JAMII’ 11 - 16 Kiunjuri apigiwa debe kuwa SHINDANO LA UANDISHI UK 9 naibu wa Ruto 2022 - UK 5 WA INSHA Jumanne, Oktoba 8, 2019 KSh30 TSh500 RFr300 taifaleo.nation.co.ke No. 20368 Asema wanasiasa hawasaidii katika vita vya kukabiliana na matumizi ya mihadarati DAWA: MATIANG'I AKOSOA VIONGOZINA CECIL ODONGO WAZIRI wa Usalama wa Nchi, Fred Matiang'i amewakashifu viongozi wa Mo Technologies kisiasa ambao ni Waislamu kwa tatizo la matumizi ya dawa za kulevya katika maeneo yao. Waziri alisema viongozi hao hawafanyi lolote kupigana na matumizi ya mihadarati akisema wao ndio wa kulaumiwa kwa kukithiri kwa tabia hiyo. “Ni vyema tuambiane ukweli. Viongozi wenu hawajafanya la kutosha kuhakikisha kwamba vita dhidi ya matumizi ya dawa za kulevya vinafaulu. WAISLAMU ENDELEA Uk 2 SGR: Polisi wanasa waandamanaji MAAFISA wa poli- VIDOKEZO Korti yaagiza si wamnyanyua a sa wa kundi la kutetea haki za MKASA WA LIKONI binadamu la Haki ukaguzi KTDA Afrika alipoka- matwa wakati wa maandamano jiji- Wapiga mbizi baada ya kilio ni Mombasa jana. Maandamano wa Afrika Kusini hayo yaliitish- cha wakulima wa kulalamikia kucheleweshwa wa ka Mombasa NA NDUNGU GACHANE kwa utekelezaji wa agizo la UK 5 MAHAKAMA imeagiza ukaguzi kufa- kukubalia malori nyiwa rekodi za fedha za Mamlaka ya Ust- kubeba mizigo awishaji wa Majani Chai (KTDA) kufuatia kutoka Bandari ya MZOZO kushuka kwa mapato ya wakulima mwaka Mombasa. Picha/ huu. Laban Walloga. JAJI Kanyi Kimondo wa Mahakama ya Waumini Murang'a aliagiza Mkaguzi wa Hesabu za HABARI KAMILI Serikali kukagua mapato ya majani chai, UK 6 bonasi na mazao yaliyowasilishwa KTDA wakataa kutoka ENDELEA Uk 2 kituo cha polisi UK 3 UHALIFU: KORTI YAELEZWA WAKILI KIMANI NA WENZAKE WALIVYONYONGWA UK 4 2 Jumanne, Oktoba 8, 2019 | TAIFA LEO Anayedaiwa kuua mtoto wa mpenzi kukaa seli Korti yaagiza Na NICHOLAS KOMU akili ili kuthibitisha ikiwa ana akili timamu. -

MONDAY PAGE 1 0910.Indd

WWW.THE-STAR.CO.KE BIG READ INDEPENDENTINDEPENDENT VOICES /THESTARKENYA FRESH AND WYCLIFFE MUGA DIFFERENT SEX FOR REGISTRA- @THESTARKENYA TION,TAKE BRIBESHEART, FOR 179 RESETTLEMENTTHIS TOO AUGUSTOCTOBER 2017 2017 FRUSTRATE OROMO THURSDAYMONDAY SHALL PASS REFUGEES AND I’m interested in personalities, not KSh60 ASYLUM SEEKERS political parties (TSh1,000,(TSh1,000, USh2,000)USh2,000) PAGESPAGE 2020-21 Sam Wyly American businessman PUZZLE JUBILEE UNSURE IF THE NASA LEADER WILL RETURN BEFORE 26TH TO TAKE PART IN ELECTION Raila off to UK, US ahead of poll Opposition chief is said to be planning to meet democrats like Johnnie Carson, some unidentifi ed State Department offi cials in the US. In London Raila will speak at Chatham House PG 4-5 WELCOME: DP Ruto, President Kenyatta, former Senator Omar and CS Balala in a jovial mood when they arrived for a leaders’ meeting in Serani Grounds, Mombasa, yesterday / CHARLES KIMANI /DPPS VOICES NEWS NEWS BUSINESS JOSEPH NYAGAH Uhuru receives Supreme Court Chase Bank Did we learn Omar as ex-senator meets today to depositors may nothing from attacks Joho and give direction on lose 25% of ’07? Raila Odinga Chebukati’s role savings PAGE 18 PAGE 2 PAGE 2 PAGE 14 2 THE-STAR.CO.KE Monday, October 9, 2017 WHAT TO DO IN CASE OF ERRORS Deputy President William Ruto, President Uhuru Kenyatta, former Mombasa Apex court Senator Hassan Omar and Tourism CS to advise on Najib Balala in Serani, Mombasa county, chair altering yesterday / PSCU Forms 34B JAMES MBAKA @onchirimbaka e Supreme Court will today give directions on whether IEBC chairman Wafula Chebukati can correct errors in the presidential election results.