Seminar 641, January 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contested Past. Anti-Brahmanical and Hindu

<TARGET "ber1" DOCINFO AUTHOR "Michael Bergunder"TITLE "Contested Past"SUBJECT "Historiographia Linguistica 31:1 (2004)"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "240"WIDTH "160"VOFFSET "2"> Contested Past Anti-Brahmanical and Hindu nationalist reconstructions of Indian prehistory* Michael Bergunder Universität Heidelberg 1. Orientalism When Sir William Jones proposed, in his famous third presidential address before the Asiatick Society in 1786, the thesis that the Sanskrit language was related to the classical European languages, Greek and Latin, and indeed to Gothic, Celtic and Persian, this was later received not only as a milestone in the history of linguistics. This newly found linguistic relationship represented at the same time the most important theoretical foundation on which European Orientalists reconstructed a pre-history of South Asia, the main elements of which achieved general recognition in the second half of the 19th century. According to this reconstruction, around the middle of the second millenium BCE, Indo-European tribes who called themselves a¯rya (Aryans) migrated from the north into India where they progressively usurped the indigenous popula- tion and became the new ruling class. In colonial India this so-called “Aryan migration theory” met with an astonishing and diverse reception within the identity-forming discourses of different people groups. The reconstruction of an epoch lying almost three to four thousand years in the past metamorphosed, in the words of Jan Assman, into an ‘internalized past’, that is, through an act of semioticization the Aryan migration was transformed into a ‘hot memory’ in Levi-Strauss’s sense, and thereby into a ‘founding history, i.e. a myth’ (Assman 1992:75–77). -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary -

Revivals of Ancient Religious Traditions in Modern India: Sāṃkhyayoga And

Revivals of ancient religious traditions in modern India: S khyayoga and Buddhism āṃ KNUT A. JACOBSEN University of Bergen Abstract The article compares the early stages of the revivals of S khyayoga and Buddhism in modern India. A similarity of S khyayoga and Buddhism was that both had disappeared from India andāṃ were re- vived in the modern period, partly based on Orientalistāṃ discoveries and writings and on the availability of printed books and publishers. Printed books provided knowledge of ancient traditions and made re-establishment possible and printed books provided a vehicle for promoting the new teachings. The article argues that absence of com- munities in India identified with these traditions at the time meant that these traditions were available as identities to be claimed. Keywords: Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Hariharānanda Āraṇya, Navayana Buddhism, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries both S khyayoga and Indian Buddhism were revived in India. In this paper I compare and contrast these revivals, and suggest why they happened. S khyayogaāṃ and Buddhism had mainly disappeared as living traditions from the central parts of India before the modern period and their absence openedāṃ them to the claims of various groups. The only living S khyayoga monastic tradition in India based on the Pātañjalayogaśāstra, the K pil Ma h tradition founded by Harihar nanda ya (1869–1947), wasāṃ a late nineteenth-century re-establishment (Jacob- sen 2018). There were no monasticā ṭ institutions of S khyayoga saṃānyāsins basedĀraṇ on the Pātañjalayogaśāstra in India in 1892, when ya became a saṃnyāsin, and his encounter with the teachingāṃ of S mkhyayoga was primarily through a textual tradition (Jacobsen 2018). -

Alankar: First Year Coursepack

LEVEL ONE WORKSHEETS The activities of the worksheet must be completed by the students. They may refer to class notes and online resources. Completed worksheets should be submitted as part of the online theory exam in the last week of February. Unfinished worksheets may be submitted with the theory exam of the following year. 1. Concepts Mangalacharan: This is the very first item a student of Odissi learns. This is an invocatory item in which one pays tribute to Mother Earth, Lord Jagannath and other Gods, also with stanzas to welcome the audience and to thank one's Gurus. "Mangala" means goodness, and "charan" mean wishing. Mangalacharan's rhythmic sequence of steps forming the Bhumi Pranam (salutation to Mother Earth) and Trikhandi Pranam (three-fold salutation to God, the Guru, and the audience) will be completed. Bhumi Pranam: The lesson starts with an brief and respectful apology to the Earth, for we are about to spend the next hour stamping on her. Tribhanga: The dancer's body is divided into three bhangas along which deflections of the head, torso and hips can take place. The technique is built on the principle of an unequal division of weight and the shift of weight from one foot to the other. The movement of the head, the torso, the hips and the knees, are important. Hip deflection is the characteristic feature of this dance style. The tribhanga is one of the most typical poses of Odissi dancing. Chowka: In this stance, weight is equally distributed and altogether four right angles create a perfect geometrical motif. -

Rtisalmar13.Pdf

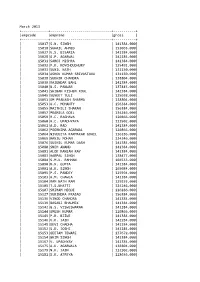

March 2013 +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ |empcode |empname |gross | +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ | 15017|S.N. SINGH | 141384.000| | 15018|SUHAIL AHMED | 153065.000| | 15027|V.S. BISARIA | 141384.000| | 15028|G.P. AGARWAL | 142184.000| | 15031|SAROJ MISHRA | 141384.000| | 15032|P.K. ROYCHOUDHURY | 125491.000| | 15033|SUNIL NATH | 131150.000| | 15034|ASHOK KUMAR SRIVASTAVA | 131150.000| | 15038|SUDHIR CHANDRA | 138804.000| | 15039|RAJENDAR BAHL | 141384.000| | 15040|B.S. PANWAR | 137445.000| | 15041|SHIBAN KISHEN KOUL | 142384.000| | 15045|SUNEET TULI | 125698.000| | 15051|OM PRAKASH SHARMA | 138804.000| | 15053|U.C. MOHANTY | 156384.000| | 15055|MAITHILI SHARAN | 156384.000| | 15057|PRAMILA GOEL | 134246.000| | 15059|R.C. RAGHAVA | 120866.000| | 15060|H.C. UPADHYAYA | 113502.000| | 15061|A.D. RAO | 141384.000| | 15062|POORNIMA AGARWAL | 120866.000| | 15064|NIVEDITA KARMAKAR GOHIL | 116186.000| | 15065|MANJU MOHAN | 134246.000| | 15076|SUSHIL KUMAR DASH | 141384.000| | 15080|SNEH ANAND | 141384.000| | 15081|ALOK RANJAN RAY | 141384.000| | 15083|HARPAL SINGH | 138477.000| | 15084|S.M.K. RAHMAN | 104533.000| | 15090|M.N. GUPTA | 141384.000| | 15091|A.K. SINGH | 165084.000| | 15095|P.S. PANDEY | 125594.000| | 15103|H.M. CHAWLA | 141384.000| | 15104|RAM NATH RAM | 129155.000| | 15105|T.S.BHATTI | 134246.000| | 15107|SRIRAM HEGDE | 116186.000| | 15127|SURINDRA PRASAD | 156384.000| | 15136|VINOD CHANDRA | 141384.000| | 15139|BASABI BHAUMIK | 141384.000| | 15142|G.S. VISWESWARAN | 141384.000| | 15144|UMESH KUMAR | 120866.000| | 15145|P.R. BIJWE | 141384.000| | 15146|V.K. JAIN | 142284.000| | 15148|DEVI CHADHA | 141384.000| | 15152|S.D. JOSHI | 141384.000| | 15153|GEETAM TEWARI | 137672.000| | 15154|BHIM SINGH | 141384.000| | 15167|V. -

July 2012 Edition

leb efJeÐeeled ogëKemeb³eesieefJe³eesieb ³eesiemebef%eleced Vol.XXVIII No.7 July, 2012 SUBSCRIPTION CONTENTS RATES 8 ` 500/- $ 50/- Editorial 2 Annual (New) 8 ` 1400/- Three Division of Yoga-Spirituality Brahmasutram 3 Year Decennial Celebrations of S-VYASA 4 8 ` 4000/- $ 500/- Bhajan Sandhya by Padmashree Anup Jalota 6 Life (10 years) Srimad Bhagawata Saptaham by Pujya Prema Pandurang Ji 8 Ganarchana – Prof. Paradesi Rao 12 Subscription in favour Division of Yoga & Life Sciences of ‘Yoga Sudha’, Dimensions of Yoga practices in HIV Bangalore by MO/ – Dr. Hemant Bhargav 13 DD only MIRT 17 Impact of 1 week of IAYT on diabetes: GDV measure 21 ADVERTISEMENT Division of Yoga & Physical Sciences TARIFF: Complete Color Research on Jyotish Astology & associated Astrological Front Inner - ` 1,20,000/- Influences... - Prof. Alex Hankey & Ramesh Rao 22 Back Outer - ` 1,50,000/- Hi am ‘FAST’ing, how can I help you? Back Inner - ` 1,20,000/- – Dr. B. Raghavendraswamy 23 Where is God - Manjeet Singh 24 Front First Inner Page - ` 1,20,000/- Division of Yoga and Management Studies Back Last Inner Page - Reader’s Forum 25 ` 1,20,000/- Yoga for Children – Dr. Tikhe Sham Ganapat 26 Full Page - ` 60,000/- YIC & ONCG SMET group 27 Half Page - ` 30,000/- Page Sponsor - ` 1,000/- Division of Yoga and Humanities Feel Free – Prof. K. Subrahmanyam 29 Dance Karanas: Perfection of Bharatha Natya Printed at: through Yoga – Mrs. Karuna Nagarajan 30 Sharadh Enterprises, Car Street, Halasuru, News Room Bangalore - 560 008 Pratishtapana of Sri Munishwara @ Giddenahalli -

Rethinking Buddhist Materialism

Special 20th Anniversary Issue Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 20, 2013 Liberation as Revolutionary Praxis: Rethinking Buddhist Materialism James Mark Shields Bucknell University Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no altera- tion is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All enquiries to: [email protected]. Liberation as Revolutionary Praxis: Rethinking Buddhist Materialism James Mark Shields1 Abstract Although it is only in recent decades that scholars have be- gun to reconsider and problematize Buddhist conceptions of “freedom” and “agency,” the thought traditions of Asian Buddhism have for many centuries struggled with ques- tions related to the issue of “liberation”—along with its fundamental ontological, epistemological and ethical im- plications. With the development of Marxist thought in the mid to late nineteenth century, a new paradigm for think- ing about freedom in relation to history, identity and social change found its way to Asia, and confronted traditional re- ligious interpretations of freedom as well as competing Western ones. In the past century, several attempts have been made—in India, southeast Asia, China and Japan—to bring together Marxist and Buddhist worldviews, with only moderate success (both at the level of theory and practice). 1 Associate Professor of Comparative -

Bhagavad Geeta – 13

|| ´ÉÏqÉ°aÉuɪÏiÉÉ || BHAGAVAD GEETA – 13 Yoga of the Field & Its Knower “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by TEXT SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA 28.13 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28.13 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse 13 ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11 Viveka Choodamani 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Isavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge A NOTE ABOUT SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities. -

Learning the Heart Way! Samyuktha

Learning the Heart Way! Samyuktha Samyuktha’s live-wire book, Learning the Heart Way , may dramatically alter the way young people think about college or university education in future. Most youngsters would like to be free of the drudgery and boredom associated with college lectures, mouldy professors, sterile guides and endless examinations. Coming from an ordinary middle-class environment in Andhra, Samyuktha decided to opt out of the ‘rat race of learning’: the endless tests and scores; the straitjacket imposed by college disciplines which actually narrowed down the world of learning to mugging badly written texts of history, political science, economics, psychology, and yes, sociology; the endless chase after MBA degrees. Instead, she created her own ‘higher education’ curriculum, one that suited both her heart and mind. The result is a marvellous book on learning’ as if the heart mattered’. Other India Press and Multiversity are delighted to be associated with a publication that will be a source of inspiration and direction to many young people (and their parents) in these days of heartless learning and soulless education. About the Author Samyuktha was born in August 1978 in New Delhi and went to school at Kalakshetra, Chennai. She trained as a handloom weaver by working with weavers in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, and subsequently learnt textile design at the National Institute of Fashion Technology. She is presently working with an enterprise of handloom weavers in Pochampalli cluster in Andhra Pradesh. She volunteers with social organizations and dreams of a world that is just and sustainable. Preface Samyuktha’s live-wire book, Learning the Heart Way, may dramatically alter the way young people think about college or university education in future. -

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List S.no Town Name Father_Name Mobile_No Pres_Address_StreetName 1 Jalesar BABY YASH PAL SINGH 7451085904 MOHALLA AKBARPUR HAVELI, JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 2 Jalesar MOHAR SHRI DEVI HAKIM SINGH 8006820002 BHAAMPURI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 3 Jalesar VIPIL KUMAR CHANDARPAL 7534009766 MOHALLA AKABRPUR HAWELI V.P.O JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 4 Jalesar GUDDO BEGUM LAL KHAN 9568203120 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 5 Jalesar CHANDRVATI VIJAY SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 6 Jalesar POONAM BHARATI MIHALLA AKABARPUR 8869865536 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 7 Jalesar SAROJ KUMARI KUWARPAL SINGH 9690823309 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 8 Jalesar MOHAMMAD FAHIM MOHAMMAD SAHID 8272897234 MOHHALA KILA , JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 9 Jalesar SHAJIYA BEGAM BABLU 9758125174 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 10 Jalesar AMIT KUMAR DAU DAYAL BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 11 Jalesar KARAN SINGH LEELADHAR BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 12 Jalesar GUDDI NAHAR SINGH 9756578025 BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 13 Jalesar MADAN MOHAN PURAN SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 14 Jalesar KANTI MUKESH KUMAR 9027022124 MOHALLA BARHAMAN PURI JALESAR ETHA 15 Jalesar SOMATI DEVI BACHCHO SINGH 7906607313 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 16 Jalesar ANITA DEVI SATYA PRAKESH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 17 Jalesar VIRENDRA SINGH AMAR SINGH 7500511574 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA,