Learning the Heart Way! Samyuktha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rukmini Devi Arundale

Rukmini Devi Arundale January 6, 2021 Rukmini Devi Arundale(1904 – 1986) “I was very intuitive from an early age. I responded to people just as I responded to art – through an inner feeling which is difficult to explain. I just felt some things were right and some were not…” Rukmini Devi was born on 29 February 1904 in Madurai of Tamilnadu. She was the first woman in Indian history to be nominated a member of the Rajya Sabha. Rukmini Devi Arundale was an Indian theosophist, dancer, and choreographer of the Indian classical dance form of Bharatnatyam, and an activist for Animal welfare. The most important revivalist of Bharatanatyam from its original ‘sadhir’ style prevalent amongst the temple dancers, the Devadasis, she also worked for the re- establishment of traditional Indian arts and crafts. She was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1956 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship in 1967. In January 1936, she along with her husband established Kalakshetra, an academy of dance and music, built around the ancient Indian Gurukul system, at Adyar, at Chennai. Today the academy is a deemed university under the Kalakshetra Foundation. She also became very close to Annie Besant and helped her with her work. She went on to become the President of the Theosophical Society after Dr. Besant’s passing and Rukmini Devi herself was an active member of the Theosophical movement. She gave her first performance at the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the Theosophical Society in 1935. Theosophists hailed her as the World Mother, to her family in Kalakshetra she is Athai (paternal aunt). -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

Quote of the Week

31st October – 6th November, 2014 Quote of the Week Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, ambition inspired, and success achieved. – Helen Keller < Click icons below for easy navigation > Through Chennai This Week, compiled and published every Friday, we provide information about what is happening in Chennai every week. It has information about all the leading Events – Music, Dance, Exhibitions, Seminars, Dining Out, and Discount Sales etc. CTW is circulated within several corporate organizations, large and small. If you wish to share information with approximately 30000 readers or advertise here, please call 98414 41116 or 98840 11933. Our mail id is [email protected] Entertainment - Film Festivals in the City Friday Movie Club @ Cholamandal presents - Film: BBC Modern Masters - Andy Warhol The first in a four-part series exploring the life and works of the 20th century's artists: Matisse; Picasso; Dali and Warhol. In this episode on Andy Warhol, Sooke explores the king of Pop Art. On his journey he parties with Dennis Hopper, has a brush with Carla Bruni and comes to grips with Marilyn. Along the way he uncovers just how brilliantly Andy Warhol pinpointed and portrayed our obsessions with consumerism, celebrity and the media. This film will be screened on 31st October, 2014 at 7.00 pm - 8.30 pm. at Cholamandal Centre for Contemporary Art (CCCA), Cholamandal Artists’ Village, Injambakkam, ECR, Chennai – 600 115. Entry is free. For more information, contact 9500105961/ 24490092 / 24494053 Entertainment – Music & Dance Bharat Sangeet Utsav 2014 Bharat Sangeet Utsav, organised by Carnatica and Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha is a well-themed concert series and comes up early in November. -

Annual Report 2017-18

KALAKSHETRA FOUNDATION 2017 - 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Our Annual Report this year features images and design elements which are from the Rukmini Devi Museum collection. This museum is found within the premises of Kalakshetra and it houses objects, books, writings, photographs, art, sculpture and many other rarities. All these artefacts were collected by Smt. Rukmini Devi during her travels or were gifted to her by friends and well- wishers from across the world. Rukmini Devi Museum Annual Report 2017-2018 INTRODuCTION Founded in the year 1936 by the KALAKSHETRA FOUNDATION legendary cultural ambassador Smt. Rukmini Devi Arundale, Kalakshetra Foundation was declared as an Institution of National Importance by an Act of Parliament in 1993. The pioneering vision of Smt. Rukmini Devi’s philosophical bedrock of ‘art without vulgarity, beauty without cruelty and education without fear’ inspires Kalakshetra. As a leading institution for teaching Bharatanatyam and Carnatic Music in the country, Kalakshetra creates a cultural ambience which nurtures the various units under it, which include the Rukmini Devi College of Fine Arts which is devoted to Bharatanatyam, Carnatic Music and the visual arts. Also,there are two high schools, a centre for weaving and natural dyeing and printing, two libraries that address the knowledge-based needs of students and scholars alike on arts and allied subjects; and a hostel for school and college students. Between April 2017 and March 2018, Kalakshetra Foundation has been involved in a range of activities in consonance with its vision to promote India’s ancient culture and set a standard of true art. Towards this, it has focussed on festivals, workshops, lectures, enhancement of its repertoire, performances, field trips and research and documentation projects as well as hosted several high profile visitors to its campus. -

Dr.S.Johnmary.Pdf

Profile Name: Dr. S. John Mary Gender: Male Female X Qualification: S. No. Degree / Diploma Subject Name of the Year of College / University Passing 1. UG – B.Sc. CHEMISTRY GTN Arts College 1992 2. B.Ed. PHYSICAL N.K.T. National College of 1995 SCIENCE Education for Women 3. PG – M.Sc. CHEMISTRY Loyola College 2001 4. M.Phil. CHEMISTRY Bharathidasan University 2007 5. Ph.D. CHEMISTRY Madurai Kamaraj 2014 University Aided X Self-Supporting Management (Day) Department: Chemistry ID No: CHE040 Total Teaching Experience at Loyola: S. No. Department Category From – To (Period) Aided / SS / Mgt (Day) / Eve 1. Chemistry Aided June 2015 – till date 2. Chemistry SS June 2009 – June 2015 Teaching Experience (in Loyola) : 8 Year Teaching Experience (Outside Loyola) : 8 Years (2001-2009) Total Teaching Experience : 16 Publications*: (International) 1. S. John Mary1, S. Rajendran2 Corrosion Behavior of SS316L in Artificial Blood Plasma in Presence of D-Glucose International Journal of Engineering Inventions, ISSN: 2278-7461, Volume 1, Issue 6 (October2012) PP: 06-12 2. S. John Mary1, S. Rajendran2 Corrosion behaviour of metals in artificial blood plasma in presence of glucose, ZAŠTITA MATERIJALA 53 (2012) broj 2 113 3. S. John Mary1, S. Rajendran2 Corrosion behaviour of metals in artificial body fluid an over view ZAŠTITA MATERIJALA 53 (2012) broj 3 189 4. N.Manimaran1, S. Rajendran2,3 , M.Manivannan4 and S. John Mary5 Corrosion inhibition of Carbon Steel by Poly Acrylamide Research journal Chemical Science Vol.2,(3) 52-57, March 2012 5. S. John Mary1, S. Rajendran2 Corrosion behaviour of SS316L in artificial blood plasma in presence of amoxicillin Portugaliae Electro Chemica Acta, April 2013 6. -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary -

University of Iowa Eco-Sensitive Low-Cost Housing: the Kerala Experience

University of Iowa Eco-sensitive Low-cost Housing: The Kerala experience India Winterim program 2011-12: December 27, 2011-January 15, 2012 Instructor: Jerry Anthony ([email protected]) Winterim India Program Coordinator: R. Rajagopal ([email protected]) Course description Good quality housing is a basic human need. However, it is not always available or if available is not priced at reasonable levels. This forces millions of families all over the world to live in bad quality or unaffordable housing, causing significant socio-economic, physical and financial problems. The scope and scale of the housing shortage is markedly greater in developing countries: one, because of the sheer number of people that need such housing, and two, because of the lack of public and private resources to address this crisis. These constraints have forced governments and non-profits in developing countries such as India to devise innovative lower-cost housing construction technologies that feature a high labor component, use many renewable resources, and have low impacts on the environment. This course will provide an extraordinary opportunity to advanced undergraduate and graduate students and interested persons from Iowa, to travel to India, interact with highly acclaimed housing professionals, learn about many innovative eco-sensitive housing techniques, and conduct independent research on a housing topic of one’s choice. All course participants will develop a clearer understanding of the conflicting challenges of economic development and environmental protection, and of culture, politics and the uneven geography of opportunity in a developing country. The course will be located in the city of Trivandrum (also called Thiruvananthapuram), the capital city of the state of Kerala. -

Alankar: First Year Coursepack

LEVEL ONE WORKSHEETS The activities of the worksheet must be completed by the students. They may refer to class notes and online resources. Completed worksheets should be submitted as part of the online theory exam in the last week of February. Unfinished worksheets may be submitted with the theory exam of the following year. 1. Concepts Mangalacharan: This is the very first item a student of Odissi learns. This is an invocatory item in which one pays tribute to Mother Earth, Lord Jagannath and other Gods, also with stanzas to welcome the audience and to thank one's Gurus. "Mangala" means goodness, and "charan" mean wishing. Mangalacharan's rhythmic sequence of steps forming the Bhumi Pranam (salutation to Mother Earth) and Trikhandi Pranam (three-fold salutation to God, the Guru, and the audience) will be completed. Bhumi Pranam: The lesson starts with an brief and respectful apology to the Earth, for we are about to spend the next hour stamping on her. Tribhanga: The dancer's body is divided into three bhangas along which deflections of the head, torso and hips can take place. The technique is built on the principle of an unequal division of weight and the shift of weight from one foot to the other. The movement of the head, the torso, the hips and the knees, are important. Hip deflection is the characteristic feature of this dance style. The tribhanga is one of the most typical poses of Odissi dancing. Chowka: In this stance, weight is equally distributed and altogether four right angles create a perfect geometrical motif. -

Rtisalmar13.Pdf

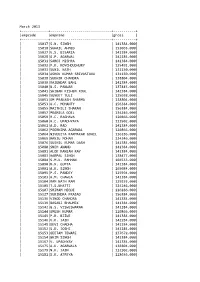

March 2013 +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ |empcode |empname |gross | +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ | 15017|S.N. SINGH | 141384.000| | 15018|SUHAIL AHMED | 153065.000| | 15027|V.S. BISARIA | 141384.000| | 15028|G.P. AGARWAL | 142184.000| | 15031|SAROJ MISHRA | 141384.000| | 15032|P.K. ROYCHOUDHURY | 125491.000| | 15033|SUNIL NATH | 131150.000| | 15034|ASHOK KUMAR SRIVASTAVA | 131150.000| | 15038|SUDHIR CHANDRA | 138804.000| | 15039|RAJENDAR BAHL | 141384.000| | 15040|B.S. PANWAR | 137445.000| | 15041|SHIBAN KISHEN KOUL | 142384.000| | 15045|SUNEET TULI | 125698.000| | 15051|OM PRAKASH SHARMA | 138804.000| | 15053|U.C. MOHANTY | 156384.000| | 15055|MAITHILI SHARAN | 156384.000| | 15057|PRAMILA GOEL | 134246.000| | 15059|R.C. RAGHAVA | 120866.000| | 15060|H.C. UPADHYAYA | 113502.000| | 15061|A.D. RAO | 141384.000| | 15062|POORNIMA AGARWAL | 120866.000| | 15064|NIVEDITA KARMAKAR GOHIL | 116186.000| | 15065|MANJU MOHAN | 134246.000| | 15076|SUSHIL KUMAR DASH | 141384.000| | 15080|SNEH ANAND | 141384.000| | 15081|ALOK RANJAN RAY | 141384.000| | 15083|HARPAL SINGH | 138477.000| | 15084|S.M.K. RAHMAN | 104533.000| | 15090|M.N. GUPTA | 141384.000| | 15091|A.K. SINGH | 165084.000| | 15095|P.S. PANDEY | 125594.000| | 15103|H.M. CHAWLA | 141384.000| | 15104|RAM NATH RAM | 129155.000| | 15105|T.S.BHATTI | 134246.000| | 15107|SRIRAM HEGDE | 116186.000| | 15127|SURINDRA PRASAD | 156384.000| | 15136|VINOD CHANDRA | 141384.000| | 15139|BASABI BHAUMIK | 141384.000| | 15142|G.S. VISWESWARAN | 141384.000| | 15144|UMESH KUMAR | 120866.000| | 15145|P.R. BIJWE | 141384.000| | 15146|V.K. JAIN | 142284.000| | 15148|DEVI CHADHA | 141384.000| | 15152|S.D. JOSHI | 141384.000| | 15153|GEETAM TEWARI | 137672.000| | 15154|BHIM SINGH | 141384.000| | 15167|V. -

July 2012 Edition

leb efJeÐeeled ogëKemeb³eesieefJe³eesieb ³eesiemebef%eleced Vol.XXVIII No.7 July, 2012 SUBSCRIPTION CONTENTS RATES 8 ` 500/- $ 50/- Editorial 2 Annual (New) 8 ` 1400/- Three Division of Yoga-Spirituality Brahmasutram 3 Year Decennial Celebrations of S-VYASA 4 8 ` 4000/- $ 500/- Bhajan Sandhya by Padmashree Anup Jalota 6 Life (10 years) Srimad Bhagawata Saptaham by Pujya Prema Pandurang Ji 8 Ganarchana – Prof. Paradesi Rao 12 Subscription in favour Division of Yoga & Life Sciences of ‘Yoga Sudha’, Dimensions of Yoga practices in HIV Bangalore by MO/ – Dr. Hemant Bhargav 13 DD only MIRT 17 Impact of 1 week of IAYT on diabetes: GDV measure 21 ADVERTISEMENT Division of Yoga & Physical Sciences TARIFF: Complete Color Research on Jyotish Astology & associated Astrological Front Inner - ` 1,20,000/- Influences... - Prof. Alex Hankey & Ramesh Rao 22 Back Outer - ` 1,50,000/- Hi am ‘FAST’ing, how can I help you? Back Inner - ` 1,20,000/- – Dr. B. Raghavendraswamy 23 Where is God - Manjeet Singh 24 Front First Inner Page - ` 1,20,000/- Division of Yoga and Management Studies Back Last Inner Page - Reader’s Forum 25 ` 1,20,000/- Yoga for Children – Dr. Tikhe Sham Ganapat 26 Full Page - ` 60,000/- YIC & ONCG SMET group 27 Half Page - ` 30,000/- Page Sponsor - ` 1,000/- Division of Yoga and Humanities Feel Free – Prof. K. Subrahmanyam 29 Dance Karanas: Perfection of Bharatha Natya Printed at: through Yoga – Mrs. Karuna Nagarajan 30 Sharadh Enterprises, Car Street, Halasuru, News Room Bangalore - 560 008 Pratishtapana of Sri Munishwara @ Giddenahalli -

Deo &Ceo Address List

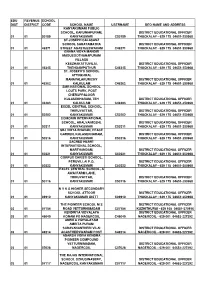

EDU REVENUE SCHOOL DIST DISTRICT CODE SCHOOL NAME USERNAME DEO NAME AND ADDRESS KANYAKUMARI PUBLIC SCHOOL, KARUNIAPURAM, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 50189 KANYAKUMARI C50189 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 ST.JOSEPH CALASANZ SCHOOL SAHAYAMATHA DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 46271 STREET AGASTEESWARAM C46271 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 GNANA VIDYA MANDIR MADUSOOTHANAPURAM VILLAGE KEEZHAKATTUVILAI, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 46345 THENGAMPUTHUR C46345 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 ST. JOSEPH'S SCHOOL ATTINKARAI, MANAVALAKURICHY DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 46362 KALKULAM C46362 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 SMR NATIONAL SCHOOL LOUTS PARK, POST CHERUPPALOOR KULASEKHARAM, TEH DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 46383 KALKULAM C46383 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 EXCEL CENTRAL SCHOOL, THIRUVATTAR, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 50202 KANYAKUMARI C50202 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 COMORIN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, ARALVAIMOZHI, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 50211 KANYAKUMARI C50211 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 SBJ VIDYA BHAVAN, PEACE GARDEN, KULASEKHARAM, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 50216 KANYAKUMARI C50216 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 SACRED HEART INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, MARTHANDAM, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 50221 KANYAKUMARI C50221 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 CORPUS CHRISTI SCHOOL, PERUVILLAI P.O, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER 01 01 50222 KANYAKUMARI C50222 THUCKALAY - 629 175 04651-250968 EXCEL CENTRAL SCHOOL, A AWAI FARM LANE, THIRUVATTAR, DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL OFFICER -

Bhagavad Geeta – 13

|| ´ÉÏqÉ°aÉuɪÏiÉÉ || BHAGAVAD GEETA – 13 Yoga of the Field & Its Knower “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by TEXT SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA 28.13 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28.13 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse 13 ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11 Viveka Choodamani 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Isavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge A NOTE ABOUT SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities.