Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

A Summary of the Broads Climate Adaptation Plan 2016

The changing Broads…? A summary of the Broads Climate Adaptation Plan 2016 CLIMATE Join the debate Contents 1 The changing Broads page 4 2 The changing climate page 4 3 A climate-smart response page 5 4 Being climate-smart in the Broads page 6 5 Managing flood risk page 12 6 Next steps page 18 Table 1 Main climate change impacts and preliminary adaptation options page 7 Table 2 Example of climate-smart planning at a local level page 11 Table 3 Assessing adaptation options for managing flood risk in the Broads page 14 Published January 2016 Broads Climate Partnership Coordinating the adaption response in the Broads Broads Authority (lead), Environment Agency, Natural England, National Farmers Union, Norfolk County Council, local authorities, University of East Anglia Broads Climate Partnership c/o Broads Authority 62-64 Thorpe Road Norwich NR1 1RY The changing Broads... This document looks at the likely impacts of climate change and sea level rise on the special features of the Broads and suggests a way forward. It is a summary of the full Broads Climate Adaptation Plan prepared as part of the UK National Adaptation Programme. To get the best future for the Broads and those who live, work and play here it makes sense to start planning for adaptation now. The ‘climate-smart’ approach led by the Broads Climate Partnership seeks to inspire and support decision makers and local communities in planning for our changing environment. It is supported by a range of information and help available through the Broads oCommunity initiative (see page 18). -

The Norfolk &. Norwich

TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK &. NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY Edited by E. A. Ellis Assistant Editor: P. W. Lambley Vol. 26 Part 1 MAY 1982 TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK AND NORWICH NATURALISTS SOCIETY Volume 26, Part 1 (May 1982) Editor Dr E. A. Ellis Assistant Editor P. W. Lambley ISSN 0375 7226 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY 1981-82 President— Dr C. P. Petch President Elect: Mr Bruce Robinson Castle Museum, Norwich Vice-Presidents: P. R. Banham, A. Bull, K. B. Clarke, K. C. Durrant, E. A. Ellis, R. Miss C. Gurney, Jones, M. J. Seago, J. A. Steers, E. L. Swann, F. J. Taylor-Page General Secretary: R. E. Baker 25 Southern Reach, Mulbarton, NR14 8BU. Tel. Mulbarton 70609 Assistant Secretary: (Membership and Publications) Miss J. Wakefield Post Office Lane, Saxthorpe, NR11 7BL Assistant Secretary: (Minutes) K. B. Clarke Excursion Secretary: Mrs J. Robinson 5 Southern Reach, Mulbarton, NR14 8BU. Tel. Mulbarton 70576 Treasurer: D. A. Dorling St Edmundsbury, 6 New Road, Hethersett. Tel. Norwich 810318 Assistant Treasurer: R. Robinson Editor: E. A. Ellis Assistant Editor: P. W. Lambley Auditor: J. E. Timbers Committee: Mr M. Baker, Miss A. Brewster, Dr A. Davy (University Representative), J. Fenton, C. Goodwin, R. Hancy, R. Hobbs (Norfolk Naturalists' Trust), P. W. Lambley (Museum Representative), Dr R. Leaney, R. P. Libbey, M. Taylor, Dr G. D. Watts, P. Wright (Nature Conservancy Representative). ORGANISERS OF PRINCIPAL SPECIALIST GROUPS Birds (Editor of the Report): M. J. Seago, 33 Acacia Road, Thorpe Mammals (Editor of the Report): R. Hancy, 124 Fakenham Road, Taverham, NR8 6QH Plants: P. W. Lambley, and E. -

Great Ideas for Discovering the Best of the Broads by Cycle

Great ideas for discovering the best of the Broads by cycle • On-road cycling routes using quiet lanes, and traffic-free cycle ways • Tips on where to cycle, taking your bike on a train and bus, and where to stop off Use a cycle to explore the tranquil beauty and natural treasures of the wetland landscapes that make up the Broads – a unique area characterised by windmills, grazing marshes, boating scenes, vast skies, reedy waters and historic settlements. There are idyllically quiet lanes and virtually no hills. If you’re touring the Broads by boat, you can stop off for a while and hire bikes from several places by the water, and see some of the area’s many other attractions. Cycling in the Broads gets you to places public transport cannot reach, and you see much that you might otherwise miss from a car or even a boat. It’s also a healthy and environmentally friendly way of getting around. Centre: How Hill (photo: Tim Locke); left and right: cycling round the Broads (photos: Broads Authority) Contents An introduction to discovering the Broads by bike, offering several itineraries in one. It starts with details of using the Bittern Line to get you to Hoveton & Wroxham, where you can hire a bike and follow Broads Bike Trails, or cycle alongside the Bure Valley Railway; how to join up with the BroadsHopper bus from rail stations; ideas for cycling in the Ludham and Hickling area; and some highlights of Sustrans NCN Route 1 from Norwich. The Broads Bike Hire Network of seven cycle hirers is listed in the last section. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Transport Strategy Consultation

If your school is in any of these Parishes then please read the letter below. Acle Fritton And St Olaves Raveningham Aldeby Geldeston Reedham Ashby With Oby Gillingham Repps With Bastwick Ashmanhaugh Haddiscoe Rockland St Mary Barton Turf Hales Rollesby Beighton Halvergate Salhouse Belaugh Heckingham Sea Palling Belton Hemsby Smallburgh Broome Hickling Somerton Brumstead Honing South Walsham Burgh Castle Horning Stalham Burgh St Peter Horsey Stockton Cantley Horstead With Stanninghall Stokesby With Herringby Carleton St Peter Hoveton Strumpshaw Catfield Ingham Sutton Chedgrave Kirby Cane Thurlton Claxton Langley With Hardley Thurne Coltishall Lingwood And Burlingham Toft Monks Crostwick Loddon Tunstead Dilham Ludham Upton With Fishley Ditchingham Martham West Caister Earsham Mautby Wheatacre East Ruston Neatishead Winterton-On-Sea Ellingham Norton Subcourse Woodbastwick Filby Ormesby St Margaret With Scratby Wroxham Fleggburgh Ormesby St Michael Potter Heigham Freethorpe Broads Area Transport Strategy Consultation Norfolk County Council is currently carrying out consultation on transport-related problems and issues around the Broads with a view to developing a transportation strategy for the Broads area. A consultation report and questionnaire has been produced and three workshops have been organised to discuss issues in more detail. The aim of this consultation exercise is to ensure that all the transport-related problems and issues have been considered, and priority areas for action have been identified. If you would like a copy of the consultation material or further details about the workshops please contact Natalie Beal on 01603 224200 (or mailto:[email protected] ). The consultation closes on 20 August 2004. Workshops Date Venue Time Tuesday 27 July Acle Recreation Centre 6 – 8pm Thursday 29 July Hobart High School, Loddon 6 - 8pm Wednesday 4 August Stalham High School, Stalham 2 - 4pm . -

Wild in the City ’ 21 May – 5 June

Wild in the City ’ 21 May – 5 June Celebrating our 90th anniversary we’ve brought our spectacular nature reserves to Norwich! Discover 10 nature reserves around the city, beautifully photographed by artist Richard Osbourne and accompanied by sounds of nature by Richard Fair. Find the last one above the doors to The Forum where Norfolk Wildlife Trust has a huge range of activities, art and wildlife experts for families and adults alike. Photo competition Eastern Daily Press is running a photo competition this summer with a special section for Norfolk Wildlife Trust all about Norfolk’s nature. Launched in May, there are categories for children and adults, with four sections in total. Pictures will be shortlisted in September. All shortlisted pictures will be printed in the EDP and there will be an exhibition and awards night with prizes in October. For more details and how to enter visit: http://nwtru.st/photocomp Find our nature reserves in these shop windows: Cotswold Outdoor HSBC Bank Dipples Museum of Norwich The Forum Dawn in early spring at Theatre Street, London Street, Swan Lane, Bridewell Alley, Millennium Plain, “ Holme Dunes is of skylark NR2 1RG NR2 1LG NR2 1JA NR2 1AQ NR2 1TF song and the whetstone NWT RANWORTH BROAD NWT HICKLING BROAD NWT FOXLEY WOOD NWT WAYLAND WOOD NWT HOLME DUNES call of grey partridge; the shrieking oystercatcher and the three-note redshank on Jessops White Stuff Jarrold The Book Hive LUSH the saltmarsh; inland the Davey Place, London Street, Bedford Street, London Street, Gentleman’s Walk, warm chomp of cattle in the NR2 1PQ NR2 1LD NR2 1DA NR2 1HL NR2 1NA grass, and the whinny still of northbound wigeon. -

Easier Access Guide

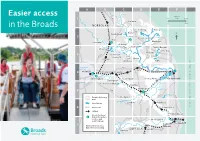

A B C D E F R Ant Easier access A149 approx. 1 0 scale 4.3m R Bure Stalham 0 7km in the Broads NORFOLK A149 Hickling Horsey Barton Neatishead How Hill 2 Potter Heigham R Thurne Hoveton Horstead Martham Horning A1 062 Ludham Trinity Broads Wroxham Ormesby Rollesby 3 Cockshoot A1151 Ranworth Salhouse South Upton Walsham Filby R Wensum A47 R Bure Acle A47 4 Norwich Postwick Brundall R Yare Breydon Whitlingham Buckenham Berney Arms Water Gt Yarmouth Surlingham Rockland St Mary Cantley R Yare A146 Reedham 5 R Waveney A143 A12 Broads Authority Chedgrave area river/broad R Chet Loddon Haddiscoe 6 main road Somerleyton railway A143 Oulton Broad Broads National Park information centres and Worlingham yacht stations R Waveney Carlton Lowesto 7 Grid references (e.g. Marshes C2) refer to this map SUFFOLK Beccles Bungay A146 Welcome to People to help you Public transport the Broads National Park Broads Authority Buses Yare House, 62-64 Thorpe Road For all bus services in the Broads contact There’s something magical about water and Norwich NR1 1RY traveline 0871 200 2233 access is getting easier, with boats to suit 01603 610734 www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk all tastes, whether you want to sit back and www.broads-authority.gov.uk enjoy the ride or have a go yourself. www.VisitTheBroads.co.uk Trains If you prefer ‘dry’ land, easy access paths and From Norwich the Bittern Line goes north Broads National Park information centres boardwalks, many of which are on nature through Wroxham and the Wherry Lines go reserves, are often the best way to explore • Whitlingham Visitor Centre east to Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft. -

Feeding Areas for Dark-Bellied Brent Geese Branta Bernicla Bernicla Around Special Protection Areas (Spas) in the UK

Feeding areas for Dark-bellied Brent Geese Branta bernicla bernicla around Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in the UK WWT Research Report Authors Helen E. Rowell & James. A. Robinson Repe JNCC/WWT Partnership March 2004 Published by: The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucestershire GL2 7BT Tel 01453 890333 Fax 01453 890827 Email [email protected] Reg. charity no. 1030884 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of WWT. This publication should be cited as: Rowell, H.E. & Robinson, J.A. 2004. Feeding areas for Dark-bellied Brent Geese Branta bernicla bernicla around Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in the UK. The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge. ii Contents List of Tables vi List of Figures vi Executive Summary vii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Feeding ecology 1 1.2 The Dark-bellied Brent Goose SPA suite 2 1.3 Aims and objectives 4 2 Methodology 5 3 Results 6 3.1 Benfleet and Southend Marshes 7 3.1.1 Site details 7 3.1.2 Location and type of inland feeding areas used 7 3.1.3 Relative importance of the inland feeding areas 7 3.2 Blackwater Estuary 8 3.2.1 Site details 8 3.2.2 Location and type of inland feeding areas used 8 3.2.3 Relative importance of the inland feeding areas 8 3.3 Chesil Beach and The Fleet 10 3.3.1 Site details 10 3.3.2 Location and type of inland feeding areas used 10 3.3.3 Relative importance of -

The Archaeology of the Broads a Review

The Archaeology of the Broads: a review For Norfolk County Council, Historic Environment Service & the Broads Authority Peter Murphy BSc MPhil MIFA Final Report December 2014 The Landscape of the Broads from Burgh Castle. This was part of the Great Estuary in the Roman period, but now shows many of the features of the modern landscape – open water, reed-swamp, grazing marsh and a farmhouse and drainage mill. Visible features of the historic environment form a key component of the landscape, easily understood by all, but buried archaeology is less well understood and less appreciated. Introduction Compared to other wetland, or former wetland, areas of the East of England the archaeology of the Broads is comparatively under-investigated (Brown et al 2000). The historic legacy of records seems scarcely to exist here. Finds made during medieval peat extraction would have gone completely unrecorded and Post-Medieval extraction of peat seems not to have been under the direction of large landowners, so the workings would have been less likely to be seen by educated individuals who could acquire and report on what was found. Bronze Age swords may not literally have been “beaten into ploughshares” – but they may have been re- cycled in other ways. Groundwater has been maintained at a higher level in many areas compared with, for example, the Fen Basin, and so deposits are often less visible and accessible. The masking of valley floor sites in the region by later alluvium further conceals low-lying sites from aerial survey and prevents conventional surface fieldwalking. Although some parts of the Broads are subject to relatively intense development for infrastructural and retail/housing development (e.g. -

Annual Report 2019–2020

Norfolk Wildlife Trust Annual report 2019–2020 Saving Norfolk’s Wildlife for the Future Norfolk Wildlife Trust seeks a My opening words are the most important message: sustainable Living Landscape thank you to our members, staff, volunteers, for wildlife and people donors, investors and grant providers. Where the future of wildlife is With your loyal and generous in the School Holidays. As part of our Greater support, and despite the Anglia partnership we promoted sustainable protected and enhanced through challenges of the current crisis, travel when discovering nature reserves. sympathetic management Norfolk Wildlife Trust will continue to advance wildlife We have also had many notable wildlife conservation in Norfolk and highlights during the year across all Norfolk Where people are connected with, to connect people to nature. habitats, from the return of the purple emperor inspired by, value and care for butterfly to our woodlands, to the creation of a Norfolk’s wildlife and wild species This report covers the year to the end of March substantial wet reedbed at Hickling Broad and 2020, a year that ended as the coronavirus Marshes in conjunction with the Environment crisis set in. Throughout the lockdown period Agency. Many highlights are the result of we know from the many photos and stories partnerships and projects which would not we received and the increased activity of our have been possible without generous support. CONTENTS online community that many people found nature to be a source of solace – often joy – in The Prime Minister had said that the Nature reserves for Page 04 difficult times. -

Cambridgeshire & Essex Butterfly Conservation

Butterfly Conservation Regional Action Plan For Anglia (Cambridgeshire, Essex, Suffolk & Norfolk) This action plan was produced in response to the Action for Butterflies project funded by WWF, EN, SNH and CCW This regional project has been supported by Action for Biodiversity Cambridgeshire and Essex Branch Suffolk branch BC Norfolk branch BC Acknowledgements The Cambridgeshire and Essex branch, Norfolk branch and Suffolk branch constitute Butterfly Conservation’s Anglia region. This regional plan has been compiled from individual branch plans which are initially drawn up from 1997-1999. As the majority of the information included in this action plan has been directly lifted from these original plans, credit for this material should go to the authors of these reports. They were John Dawson (Cambridgeshire & Essex Plan, 1997), James Mann and Tony Prichard (Suffolk Plan, 1998), and Jane Harris (Norfolk Plan, 1999). County butterfly updates have largely been provided by Iris Newbery and Dr Val Perrin (Cambridgeshire and Essex), Roland Rogers and Brian Mcllwrath (Norfolk) and Richard Stewart (Suffolk). Some of the moth information included in the plan has been provided by Dr Paul Waring, David Green and Mark Parsons (BC Moth Conservation Officers) with additional county moth data obtained from John Dawson (Cambridgeshire), Brian Goodey and Robin Field (Essex), Barry Dickerson (Huntingdon Moth and Butterfly Group), Michael Hall and Ken Saul (Norfolk Moth Survey) and Tony Prichard (Suffolk Moth Group). Some of the micro-moth information included in the plan was kindly provided by A. M. Emmet. Other individuals targeted with specific requests include Graham Bailey (BC Cambs. & Essex), Ruth Edwards, Dr Chris Gibson (EN), Dr Andrew Pullin (Birmingham University), Estella Roberts (BC, Assistant Conservation Officer, Wareham), Matthew Shardlow (RSPB) and Ken Ulrich (BC Cambs.