Advisory Visit River Bure, Blickling Estate, Norfolk December 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy

Appendix A Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Consultation Draft March 2015 1 Blank 2 Part One - Flooding and Flood Risk Management Contents PART ONE – FLOODING AND FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT ..................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 5 2 What Is Flooding? ........................................................................... 8 3. What is Flood Risk? ...................................................................... 10 4. What are the sources of flooding? ................................................ 13 5. Sources of Local Flood Risk ......................................................... 14 6. Sources of Strategic Flood Risk .................................................... 17 7. Flood Risk Management ............................................................... 19 8. Flood Risk Management Authorities ............................................. 22 PART TWO – FLOOD RISK IN NORFOLK .................................................. 30 9. Flood Risk in Norfolk ..................................................................... 30 Flood Risk in Your Area ................................................................ 39 10. Broadland District .......................................................................... 39 11. Breckland District .......................................................................... 45 12. Great Yarmouth Borough .............................................................. 51 13. Borough of King’s -

Bridge Barn Spinks Lane | Heydon | Norfolk | NR11 6RF BIG SKY COUNTRY

Bridge Barn Spinks Lane | Heydon | Norfolk | NR11 6RF BIG SKY COUNTRY “Wide open horizons, far reaching views, spectacular sunrises enjoyed from your door, there’s no light pollution and no neighbours to disturb, if you want the perfect paradise, this barn you’ll adore. A home with real heart, finished with attention to detail, the sense of quality throughout is clear, while the outbuilding and plot have potential in spades, the location an attraction and a place to hold dear.” KEY FEATURES • An Impressive and Versatile Converted Barn, standing in 2.75 acres of Formal Gardens • Four Bedrooms; Two Bathrooms; Two Receptions • Stunning Open Plan Kitchen; Separate Utility • Contemporary Wooden Staircase; Fireplace with Wood Burner • A wonderful Secluded Location, with No Near Neighbours, yet within Striking Distance of the Market Town of Holt • A Large Range of Outbuildings; Triple Cart Lodge; Additional Parking • Stunning Views in All Directions • The Accommodation extends to 2,838sq.ft • Energy Rating: E On a quiet lane surrounded by open countryside, this barn-style home sits in just under three acres of land, including a large workshop with office and full plumbing. It’s all set between the attractive and desirable towns of Aylsham and Holt, close to the North Norfolk coast and to a number of pretty villages. Whether it’s walking or stargazing, growing your own or horse riding, whether you want a traditional home or a modern build, a workshop or a large garden, this one ticks so many boxes and really has to be seen to be fully appreciated. The Character And The Contemporary This is effectively a modern home, having been built from the site of a bungalow around a decade ago. -

Marriott's Way Walking and Cycling Guide

Marriott’s Way Walking and Cycling Guide 1 Introduction The routes in this guide are designed to make the most of the natural Equipment beauty and cultural heritage of Marriott’s Way, which follows two disused Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or shoes is essential for train lines between the medieval city of Norwich and the historic market the longer routes. Some of Marriott’s Way can be muddy so in some areas a town of Aylsham. Funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, they are a great way road bike may not be suitable and appropriate footwear is advised. Norfolk’s to delve deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful climate is drier than much of the county but unfortunately we can’t array of habitats await, many of which are protected areas, home to rare guarantee sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you are wildlife. The railway heritage is not the only history you will come across, as lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget sun cream and there are a series of churches and old villages to discover. a hat. With loops from one mile to twelve, there’s a distance for everyone here, whether you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. The landscape is particularly flat, with gradients being kept The walks and cycle loops described in these pages are well signposted to a minimum from when it was a railway, but this does not stop you feeling on the ground and detailed downloadable maps are available for each at like you’ve had a challenge. -

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

A Summary of the Broads Climate Adaptation Plan 2016

The changing Broads…? A summary of the Broads Climate Adaptation Plan 2016 CLIMATE Join the debate Contents 1 The changing Broads page 4 2 The changing climate page 4 3 A climate-smart response page 5 4 Being climate-smart in the Broads page 6 5 Managing flood risk page 12 6 Next steps page 18 Table 1 Main climate change impacts and preliminary adaptation options page 7 Table 2 Example of climate-smart planning at a local level page 11 Table 3 Assessing adaptation options for managing flood risk in the Broads page 14 Published January 2016 Broads Climate Partnership Coordinating the adaption response in the Broads Broads Authority (lead), Environment Agency, Natural England, National Farmers Union, Norfolk County Council, local authorities, University of East Anglia Broads Climate Partnership c/o Broads Authority 62-64 Thorpe Road Norwich NR1 1RY The changing Broads... This document looks at the likely impacts of climate change and sea level rise on the special features of the Broads and suggests a way forward. It is a summary of the full Broads Climate Adaptation Plan prepared as part of the UK National Adaptation Programme. To get the best future for the Broads and those who live, work and play here it makes sense to start planning for adaptation now. The ‘climate-smart’ approach led by the Broads Climate Partnership seeks to inspire and support decision makers and local communities in planning for our changing environment. It is supported by a range of information and help available through the Broads oCommunity initiative (see page 18). -

Canoe and Kayak Licence Requirements

Canoe and Kayak Licence Requirements Waterways & Environment Briefing Note On many waterways across the country a licence, day pass or similar is required. It is important all waterways users ensure they stay within the licensing requirements for the waters the use. Waterways licences are a legal requirement, but the funds raised enable navigation authorities to maintain the waterways, improve facilities for paddlers and secure the water environment. We have compiled this guide to give you as much information as possible regarding licensing arrangements around the country. We will endeavour to keep this as up to date as possible, but we always recommend you check the current situation on the waters you paddle. Which waters are covered under the British Canoeing licence agreements? The following waterways are included under British Canoeing’s licensing arrangements with navigation authorities: All Canal & River Trust Waterways - See www.canalrivertrust.org.uk for a list of all waterways managed by Canal & River Trust All Environment Agency managed waterways - Black Sluice Navigation; - River Ancholme; - River Cam (below Bottisham Lock); - River Glen; - River Great Ouse (below Kempston and the flood relief channel between the head sluice lock at Denver and the Tail sluice at Saddlebrow); - River Lark; - River Little Ouse (below Brandon Staunch); - River Medway – below Tonbridge; - River Nene – below Northampton; - River Stour (Suffolk) – below Brundon Mill, Sudbury; - River Thames – Cricklade Bridge to Teddington (including the Jubilee -

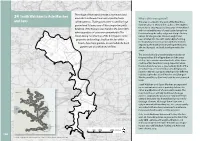

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

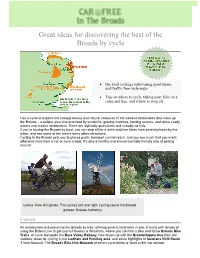

Great Ideas for Discovering the Best of the Broads by Cycle

Great ideas for discovering the best of the Broads by cycle • On-road cycling routes using quiet lanes, and traffic-free cycle ways • Tips on where to cycle, taking your bike on a train and bus, and where to stop off Use a cycle to explore the tranquil beauty and natural treasures of the wetland landscapes that make up the Broads – a unique area characterised by windmills, grazing marshes, boating scenes, vast skies, reedy waters and historic settlements. There are idyllically quiet lanes and virtually no hills. If you’re touring the Broads by boat, you can stop off for a while and hire bikes from several places by the water, and see some of the area’s many other attractions. Cycling in the Broads gets you to places public transport cannot reach, and you see much that you might otherwise miss from a car or even a boat. It’s also a healthy and environmentally friendly way of getting around. Centre: How Hill (photo: Tim Locke); left and right: cycling round the Broads (photos: Broads Authority) Contents An introduction to discovering the Broads by bike, offering several itineraries in one. It starts with details of using the Bittern Line to get you to Hoveton & Wroxham, where you can hire a bike and follow Broads Bike Trails, or cycle alongside the Bure Valley Railway; how to join up with the BroadsHopper bus from rail stations; ideas for cycling in the Ludham and Hickling area; and some highlights of Sustrans NCN Route 1 from Norwich. The Broads Bike Hire Network of seven cycle hirers is listed in the last section. -

Transport Strategy Consultation

If your school is in any of these Parishes then please read the letter below. Acle Fritton And St Olaves Raveningham Aldeby Geldeston Reedham Ashby With Oby Gillingham Repps With Bastwick Ashmanhaugh Haddiscoe Rockland St Mary Barton Turf Hales Rollesby Beighton Halvergate Salhouse Belaugh Heckingham Sea Palling Belton Hemsby Smallburgh Broome Hickling Somerton Brumstead Honing South Walsham Burgh Castle Horning Stalham Burgh St Peter Horsey Stockton Cantley Horstead With Stanninghall Stokesby With Herringby Carleton St Peter Hoveton Strumpshaw Catfield Ingham Sutton Chedgrave Kirby Cane Thurlton Claxton Langley With Hardley Thurne Coltishall Lingwood And Burlingham Toft Monks Crostwick Loddon Tunstead Dilham Ludham Upton With Fishley Ditchingham Martham West Caister Earsham Mautby Wheatacre East Ruston Neatishead Winterton-On-Sea Ellingham Norton Subcourse Woodbastwick Filby Ormesby St Margaret With Scratby Wroxham Fleggburgh Ormesby St Michael Potter Heigham Freethorpe Broads Area Transport Strategy Consultation Norfolk County Council is currently carrying out consultation on transport-related problems and issues around the Broads with a view to developing a transportation strategy for the Broads area. A consultation report and questionnaire has been produced and three workshops have been organised to discuss issues in more detail. The aim of this consultation exercise is to ensure that all the transport-related problems and issues have been considered, and priority areas for action have been identified. If you would like a copy of the consultation material or further details about the workshops please contact Natalie Beal on 01603 224200 (or mailto:[email protected] ). The consultation closes on 20 August 2004. Workshops Date Venue Time Tuesday 27 July Acle Recreation Centre 6 – 8pm Thursday 29 July Hobart High School, Loddon 6 - 8pm Wednesday 4 August Stalham High School, Stalham 2 - 4pm . -

Strategic River Surveys 1998

E n v ir o n m e n t Environment Agency Anglian Region BEnvironm F A ental S MStrategic o River n i Surveys t o r1998 i n g Final Issue July 1999 E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR E n v i r o n m e n t A g e n c y BROADLAND FLOOD ALLEVIATION STRATEGY ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING STRATEGIC RIVER SURVEYS 1998 JULY 1999 Prepared for the Environment Agency Anglian Region ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 125436 Job code Issue Revision Description EAFEP 2 1 Final Date Prepared by Checked by Approved by 28.7.99 E.K.Butler N.Wood J.Butterworth M.C.Padfield BFAS Environmental Monitoring: Strategic River Surveys Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Broadiand Flood Alleviation Strategy - Aim and Objectives 5 1~.2 Broadland Flood Alleviation Strategy - Development of Environmental Monitoring 6 13 Strategic Monitoring in 1998 = _ 7 1.4 Introduction to the Strategic River Surveys Report 8 2. ANALYSIS OF HISTORIC WATER QUALITY AND HYDROMETRIC DATA11 2.1 Objectives .11 2.2 Introduction 11 23 Collection and Availability of Data 11 2.4 Methods of Analysis 18 2.5 Results 20 2.6 Conclusions 28 2.7 Recommendations 28 3. SALINITY SURVEYS 53 3.1 Objectives 53 3.2 Introduction . 53 3 3 Methods ' 53 3.4 Results and Discussion 56 3.5 Conclusions 59 3.6 Recommendations 59 4. INVERTEBRATE MONITORING 70 4.1 Objectives 70 4.2 Introduction 70 4 3 Methods 70 4.4 Results 72 4.5 Discussion 80 4.6 Conclusions and Recommendations 80 K: \broadrnon\reprts98\rivrpt.doc 1 Scott Wilson BFAS Environmental Monitoring: Strategic River Surveys 5. -

Proposals to Spend £1.5M of Additional Funding from Norfolk County Council

App 1 Proposals to spend £1.5m of additional funding from Norfolk County Council District Area Road Number Parish Road Name Location Type of Work Estimated cost Breckland South B1111 Harling Various HGV Cell Review Feasibility £10,000 Breckland West C768 Ashill Swaffham Road near recycle centre Resurfacing 8,164 Breckland West C768 Ashill Swaffham Road on bend o/s Church Resurfacing 14,333 Breckland West 33261 Hilborough Coldharbour Lane nearer Gooderstone end Patching 23,153 Breckland West C116 Holme Hale Station Road jnc with Hale Rd Resurfacing 13,125 Breckland West B1108 Little Cressingham Brandon Road from 30/60 to end of ind. Est. Resurfacing 24,990 Breckland West 30401 Thetford Kings Street section in front of Kings Houseresurface Resurface 21,000 Breckland West 30603 Thetford Mackenzie Road near close Drainage 5,775 £120,539 Broadland East C441 Blofield Woodbastwick Road Blofield Heath - Phase 2 extension Drainage £15,000 Broadland East C874 Woodbastwick Plumstead Road Through the Shearwater Bends Resurfacing £48,878 Broadland North C593 Aylsham Blickling Road Blickling Road Patching £10,000 Broadland North C494 Aylsham Buxton Rd / Aylsham Rd Buxton Rd / Aylsham Rd Patching £15,000 Broadland North 57120 Aylsham Hungate Street Hungate Street Drainage £10,000 Broadland North 57099 Brampton Oxnead Lane Oxnead Lane Patching £5,000 Broadland North C245 Buxton the street the street Patching £5,000 Broadland North 57120 Horsford Mill lane Mill lane Drainage £5,000 Broadland North 57508 Spixworth Park Road Park Road Drainage £5,000 Broadland -

Norfolk Health, Heritage and Biodiversity Walks

Norfolk health, heritage and biodiversity walks Aylsham Cromer Road Reepham • Buxton • Blickling • Cawston • Marsham Peterson’s Lane Weavers Way Blickling Road Heydon Road DismantledRailway Start Holman Road Abel Heath Norfolk County Council at your service Contents folk or W N N a o r f o l l k k C o u s n t y C o u n c y i it l – rs H ve e di alth io Introduction page 2 • Heritage • B Walk 1 Aylsham: starter walks page 6 Walk 2 Aylsham: Weavers’ Way and Drabblegate page 10 Walk 3 Aylsham: Marriott’s Way and Green Lane page 14 Walk 4 Aylsham: Abel Heath and Silvergate page 18 Walk 5 Aylsham town walk page 22 Walk 6 Blickling via Moorgate page 26 Walk 7 Marsham via Fengate page 30 Walk 8 Cawston via Marriott’s Way page 34 Walk 9 Reepham; Marriott’s Way and Catchback Lane page 38 Walk 10 Reepham via Salle Church page 42 Walk 11 Buxton via Brampton page 46 Walk 12 Buxton via Little Hautbois page 50 Further information page 56 1 Introduction ontact with natural surroundings offers a restorative These circular walks have been carefully designed to encourage you to Cenvironment which enables you to relax, unwind and re-charge your explore the local countryside, discover urban green spaces and to enjoy batteries helping to enhance your mood and reduce stress levels. the heritage of Norfolk, both natural and man made. The routes explore Regular exercise can help to prevent major conditions, such as coronary Aylsham and local surrounding villages.