The Future of Natural Resources Law, 47 Envtl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

= Roster - ~ : of Members

:1111111111111 "1"'111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111E § i = = ~ ~ = ROSTER - ~ : OF MEMBERS - OF THE 353RD - - INFANTRY i - - - - - - - = - - -ill lit IIIIIUUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIU UWtMtltolllllllll U UIUU I U 11111111 U I uro- iiiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii', THE 353RD INFANTRY | REGIMENTAL SOCIETY I SEPTEMBER. 1917 | JUNE. 1919 I IllltllUtll ................................................................................................. ..... ROSTER m u ......... ACCORDING TO THE PLACE ............... OF RESIDENCE iiiiiiiiiiii ......................................................... PREPARED FOR D 1 S T R IB U T 1 0 N TO ..... MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY AT THE REGIMENTAL REUNION. SEPTEMBER. 1922 ................................ n 1111111111111 • 111111111<111111111111111111111•111111111•11111111ii11111111 it iiiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiHimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiumiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiintiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiifiiiiiiiiiiiiMiMiiiiiiiiMiiic1111111111«11111111111111 ■ 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 llj; PREFACE This little booklet contains the names and addresses of all former members of the Regiment whose names and addresses were known at the time the book was com piled. There are bound to be er rors. Men move from place to place and very seldom think of notifying the Secretary of change of address. This book is Intended to encour age visiting among former mem bers of the Regiment. It is too bad it cannot be absolutely cor rect for the will to visit a former -

Saving the Salish Sea: a Fight for Tribal Sovereignty and Climate Action

Saving the Salish Sea: A Fight for Tribal Sovereignty and Climate Action Evaluator: Francesca Hillary Member of Round Valley Tribes, Public Affairs and Communications Specialist, Frogfoot Communications, LLC. Instructor: Patrick Christie Professor Jackson School of International Studies and School of Marine and Environmental Affairs ______________________________________________________________________ Coordinator: Editor: Casey Proulx Ellie Tieman Indigenous Student Liaison: Jade D. Dudoward Authors: Jade D. Dudoward Hannah Elzig Hanna Lundin Lexi Nguyen Jamie Olss Casey Proulx Yumeng Qiu Genevieve Rubinelli Irene Shim Mariama Sidibe Rachel Sun Ellie Tieman Shouyang Zong University of Washington Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies Seattle, Washington March 4, 2021 - 2 - - 3 - 1. Introduction 6 2. Social and Ecological Effects of Trans Mountain Extension 6 2.1. Alberta Tar Sands 8 2.2. The Coast Salish Peoples 10 2.3. Trans Mountain Expansion Project 11 2.3.1. Ecological Impacts Of Trans Mountain Expansion Project 16 2.3.2. Social Impacts Of Trans Mountain Expansion Project 20 2.4. Policy Recommendations 27 2.5. Conclusion 30 3. Social Movements and Allyship Best Practices 31 3.1. Tactics from Past Social Movements for TMX Resistance 31 3.1.1. The Fish Wars 32 3.1.2. A Rise of a New Priority 34 3.1.3 Social Movements and Opposition Tactics 35 3.1.3.1. Keystone XL 35 3.1.3.2. Dakota Access Pipeline 37 3.1.4. Steps To Stronger Allyship 38 3.1.5. Resistance Is Not Futile; It Is To Make Changes 40 3.2. Present Social Movements in Regards to TMX 40 3.2.1. -

The War on Poverty, Lawyers, and the Tribal Sovereignty Movement, 1964-1974

‘The Sovereignty that Seemed Lost Forever’: The War on Poverty, Lawyers, and the Tribal Sovereignty Movement, 1964-1974 Aurélie A. Roy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Aurélie A. Roy All rights reserved ‘The Sovereignty that Seemed Lost Forever’1: The War on Poverty, Lawyers, and the Tribal Sovereignty Movement, 1964-1974 Aurélie A. Roy ABSTRACT Relying on interviews of Indian rights lawyers as well as archival research, this collective history excavates a missing page in the history of the modern tribal sovereignty movement. At a time when vocal Native American political protests were raging from Washington State, to Alcatraz Island, to Washington, D.C., a small group of newly graduated lawyers started quietly resurrecting Indian rights through the law. Between 1964 and 1974, these non-Indian and Native American lawyers litigated on behalf of Indians, established legal assistance programs as part of the War on Poverty efforts to provide American citizens with equal access to a better life, and founded institutions to support the protection of tribal rights. In the process, they would also inadvertently create both a profession and an academic field—Indian law as we know it today— which has since attracted an increasing number of lawyers, including Native Americans. This story is an attempt at reconstituting a major dimension of the rise of tribal sovereignty in the postwar era, one that has until now remained in the shadows of history: how Indian rights, considered obsolete until the 1960s, gained legitimacy by seizing a series of opportunities made available in part through ‘accidents’ of history. -

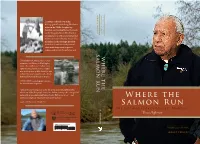

Where the Salmon Run: the Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr

LEGACY PROJECT A century-old feud over tribal fishing ignited brawls along Northwest rivers in the 1960s. Roughed up, belittled, and handcuffed on the banks of the Nisqually River, Billy Frank Jr. emerged as one of the most influential Indians in modern history. Inspired by his father and his heritage, the elder united rivals and survived personal trials in his long career to protect salmon and restore the environment. Courtesy Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission salmon run salmon salmon run salmon where the where the “I hope this book finds a place in every classroom and library in Washington State. The conflicts over Indian treaty rights produced a true warrior/states- man in the person of Billy Frank Jr., who endured personal tragedies and setbacks that would have destroyed most of us.” TOM KEEFE, former legislative director for Senator Warren Magnuson Courtesy Hank Adams collection “This is the fascinating story of the life of my dear friend, Billy Frank, who is one of the first people I met from Indian Country. He is recognized nationally as an outstanding Indian leader. Billy is a warrior—and continues to fight for the preservation of the salmon.” w here the Senator DANIEL K. INOUYE s almon r un heffernan the life and legacy of billy frank jr. Trova Heffernan University of Washington Press Seattle and London ISBN 978-0-295-99178-8 909 0 000 0 0 9 7 8 0 2 9 5 9 9 1 7 8 8 Courtesy Michael Harris 9 780295 991788 LEGACY PROJECT Where the Salmon Run The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. -

Iacp New Members

44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 200 | Alexandria, VA 22314, USA | 703.836.6767 or 1.800.THEIACP | www.theIACP.org IACP NEW MEMBERS New member applications are published pursuant to the provisions of the IACP Constitution. If any active member in good standing objects to an applicant, written notice of the objection must be submitted to the Executive Director within 60 days of publication. The full membership listing can be found in the online member directory under the Participate tab of the IACP website. Associate members are indicated with an asterisk (*). All other listings are active members. Published September 1, 2020. Bangladesh Sharaiatpur Zila *Ashrafuzzaman, SM, Superintendent of Police, Bangladesh Police Brazil Sao Paulo Gomes Bento, Alexander, Colonel, Policia Militar do Estado de Sao Paulo Canada Manitoba Thompson *Martin, Clovis, Constable/DRE, RCMP Treherne *Kennedy, Carrie, Sergeant, RCMP Ontario Kenora *Taman, Jordan, Constable, Ontario Provincial Police Ottawa *Zafar, Aiesha, Director General, Canada Border Services Agency Toronto Speid, Jahmar, Criminal Investigations Supervisor, Canadian Forces Military Police Colombia Cali *Tabares, Wilmer, Traffic Agent, Secretary Traffic Cali United Kingdom Newcastle-upon-Tyne *Oxburgh, Gavin, Professor, New Castle Univ United States Alabama Daleville *Medley, Allan, Chief, Daleville Dept of Public Safety Eufaula Watkins, Steve, Chief of Police, Eufaula Police Dept Fairhope Hollinghead, Stephanie, Chief of Police, Fairhope Police Dept Mobile Smith, Rassie, Captain, Mobile Co Sheriff's -

Washington Shellfish Aquaculture: Assessment of the Current Regulatory Frameworks

Washington Shellfish Aquaculture: Assessment of the Current Regulatory Frameworks Raye Evrard A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2017 Committee: Terrie Klinger Brent Vadopalas Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Marine and Environmental Affairs ©Copyright 2017 Raye Evrard Abstract Washington Shellfish Aquaculture: Assessment of the Current Regulatory Frameworks Raye Evrard Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Department Director Terrie Klinger School of Marine and Environmental Affairs The Washington shellfish aquaculture regulatory framework is a complex instrument with numerous permits and high agency involvement. Shellfish business owners, industry officials and policy-makers look to simplify the overall process by reducing paperwork and permit redundancies. In the past, the Washington aquaculture sector held a close relationship with the Washington Department of Agriculture, and policy- makers are again assessing a closer future relationship, aiding in regulatory efficiency. The purpose of this study is to locate sources of inefficiency within the shellfish aquaculture regulatory framework and supply new ideas for future policy-making based on an aquaculture regulatory framework proposed by Takoukam and Erikstein (2013). There are four main objectives to this study. The first is to identify barriers within the regulatory framework from the federal scale to the county level restricting the Washington shellfish industry. Through scientific and governmental literature reviews, and information from conference attendance, these barriers are identified. The second objective is to showcase current programs addressing regulatory barriers in aquaculture. Current programs are the Shellfish Interagency Permitting Team, the Pacific Aquaculture Caucus, and the Pacific Coast Shellfish Growers Association. -

COLUMBIA Index, 1987-1996, Volumes 1

COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History index 1987-1996 Volumes One through Ten Compiled by Robert C. Carriker and Mary E. Petty Published by the WashingtonState Historical Society with assistancefrom the WilliamL. DavisS.J Endowment of Gonzaga University Tacoma, Washington 1999 COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History index 1987-1996 Volumes One through Ten EDITORS John McClelland, Jr., Interim Editor (1987-1988) and Founding Editor (1988-1996) David L. Nicandri, ExecutiveEditor (1988-1996) Christina Orange Dubois, AssistantEditor (1988-1991) and ManagingEditor/Desi gner (1992-1996) Robert C. Carriker, Book Review Editor ( 1987-1996) Arthur Dwelley, Associate Editor( 1988-1989) Cass Salzwedel, AssistantEditor (1987-1988) ArnyShepard Hines, Designer (1987-1991) Carolyn Simonson, CopyEditor ( 1991-1996) MANAGEMENT Christopher Lee, Business Manager (1988-1996) Gladys C. Para, CirculationManrtger (1987-1988) Marie De Long, Circulation Manager (1989-1996) EDITORIAL ADVISORS Knute 0. Berger (1987-1989) David M. Buerge (1987-1990) Keith A. Murray ( 1987-1989) J. William T. Youngs (1987-1991) Harold P. Simonson (1988-1989) Robert C. Wing (1989-1991) Arthur Dwelley (1990-1991) Robert A. Clark (1991) William L. Lang (1991-1992) STAFF CONTRIBUTORS Elaine Miller (1988-1996) JoyWerlink (1988-1996) Richard Frederick (1988-1996) Edward Nolan (1989-1996) Copyright © 1999 Washington State Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission fromthe publisher. ISBN 0-917048-72-5 Printed in the United States of America by Johnson-Cox Company INTRODUCTION COLUMBIA's initial index is the result of a two-year collaborative effort by a librarian and a historian. Standards established by professionals in the field were followed. -

Flooded by Progress: Law, Natural Resources, and Native Rights in the Postwar Pacific Northwest

Flooded by Progress: Law, Natural Resources, and Native Rights in the Postwar Pacific Northwest By John James Dougherty A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Thomas Biolsi, Chair Professor Mark Brilliant Professor Shari Huhndorf Professor Beth Piatote Spring 2014 Flooded by Progress: Law, Natural Resources, and Native Rights in the Postwar Pacific Northwest Copyright © John James Dougherty All Rights Reserved Abstract Flooded by Progress: Law, Natural Resources, and Native Rights in the Postwar Pacific Northwest By John James Dougherty Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Thomas Biolsi, Chair This dissertation examines the politics of federal Indian law and the changing economic and environmental landscape of the postwar Pacific Northwest. In particular, it contends that the changing legal status of Native lands and resources was instrumental in both the massive industrial expansion, and subsequent environmental transformation, of the postwar Pacific Northwest. It traces the relations between economic and environmental changes and their connections to the dramatic policy shift in Indian affairs from the early 1950s, when the federal government unilaterally terminated tribal status of 109 Native communities, most of them in the Pacific Northwest, to the Native sovereignty movement, which precipitated new national policies of self-determination in the 1970s. Not only does the dissertation illuminate how Native communities in the Pacific Northwest were inequitably burdened by the region’s environmental and economic transformations in the second half of the 20th century, it also demonstrates how these transformations fueled the national economy in the postwar years as well as the emergence of Native activism, and how Native communities actively navigated and influenced seminal directions in federal Indian policy. -

The Making of Modern Indian Law

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2006 "Peoples Distinct from Others": The Making of Modern Indian Law Charles Wilkinson University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Litigation Commons Citation Information Charles Wilkinson, "Peoples Distinct from Others": The Making of Modern Indian Law, 2006 Utah L. Rev. 379, available at http://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/384/. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 2006 Utah L. Rev. 379 2006 Provided by: William A. Wise Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue Mar 28 16:21:23 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information "Peoples Distinct from Others": The Making of Modern Indian Law Charles Wilkinson* I. -

State.S Court Directory

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. .,-----, - -------- t...' .... ,.* ,~/~ .., " • \.-,' UNITED· STATE.S COURT DIRECTORY FEBRUARY 1, 1980 ' , , ' ., • ' I • ",' , t " ~ UNITED STATES COURT DIRECTORY • February 1, 1980 Published by: The Administrative Office of the United States Courts Contents: Division of Personnel Office of the Chief (633-6115) Publication & Distribution: Administrative Services Division Management Services B.ranch Chief, Publications Management Section (633-6178) • , 1- ~ .... • ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS WASHINGTON, D.C. 20544 .~ WILLIAM E. FOLE' R. GLENN JOHNSON DIRECTOR CHIEF OF THE DIVISION OF PERSONNEL JOSEi"H F. SPANIOL, JR. DEPUTY DI RECTOR April 7, 1980 MEM)RANDUM '10 AIL lNITED STATES JUDGES, lNITED STATES MA.GLSTRATES, CIRCUIT EXECUl'IVES, FEIERAL PUBLIC DEFENDERS, CLERKS OF CDURT, PROBATION OFFICERS, AND PRE'l'RIAL SERVICES OFFICERS SUBJECl': February 1, 1980 Issue of the thited States Court Directory Enclos(!d you will f:ind a copy of the current issue of the thited States Court Directory which includes listings for U'lited States Magistrates. Listed below are changes which have occurred in the F'ebruary 1, 1980 directory which should be corrected. In order to keep this publication as current as possible, we ask that court officials notify the Division of Persormel of any other changes that should be corrected or whEnever there is a m:ri.ling address or telephone change. Change 2 District of Colunhia Circuit -- Add Judge Harry T. Ed-lards, ~\Washington, D. C. 20001, (202-426-7493). fulete Michael Davidson as SEnior Staff Attorney and add Christine N. Kohl. 4 Second Circuit -- fulete Senior Judge Paul R. -

Inspirational Leadership Curriculum for Grades 8-12

The National Native American Hall of Fame recognizes and honors the inspirational achievements of Native Americans in contemporary history For Teachers This Native American biography-based curriculum is designed for use by teachers of grade levels 8-12 throughout the nation, as it meets national content standards in the areas of literacy, social studies, health, science, and art. The lessons in this curriculum are meant to introduce students to noteworthy individuals who have been inducted into the National Native American Hall of Fame. Students are meant to become inspired to learn more about the National Native American Hall of Fame and the remarkable lives and contributions of its inductees. Shane Doyle, EdD From the CEO We, at the National Native American Hall of Fame are excited and proud to present our “Inspirational Leadership” education curriculum. Developing educational lesson plans about each of our Hall of Fame inductees is one of our organization’s key objectives. We feel that in order to make Native Americans more visible, we need to start in our schools. Each of the lesson plans provide educators with great information and resources, while offering inspiration and role models to students. We are very grateful to our supporters who have funded the work that has made this curriculum possible. These funders include: Northwest Area Foundation First Interstate Bank Foundation NoVo Foundation Dennis and Phyllis Washington Foundation Foundation for Community Vitality O.P. and W.E. Edwards Foundation Tides Foundation Humanities Montana National Endowment for the Humanities Chi Miigwech! James Parker Shield Watch our 11-minute introduction to the National Native American Hall of Fame “Inspirational Leadership Curriculum” featuring Shane Doyle and James Parker Shield at https://vimeo.com/474797515 The interview is also accessible by scanning the Quick Response (QR) code with a smartphone or QR Reader. -

40 Years After Boldt, the Fight Goes on Over Fewer and Fewer Fish | Pacific NW | the Seattle Times

40 years after Boldt, the fight goes on over fewer and fewer fish | Pacific NW | The Seattle Times Mobile | Newsletters | RSS | Subscribe | Subscriber services Your profile | Commenter Log in | Subscriber Log In | Contact/Help Monday, February 10, 2014 TRAFFIC 48°F Follow us: Pacific NW Magazine Winner of Nine Pulitzer Prizes Advanced Search | Events & Venues | Obituaries Home News Business & Tech Sports Entertainment Food Living Homes Travel Opinion Jobs Autos Shopping IN THE NEWS: Sochi Olympics Westminster dog show Patty Murray Obamacare Mark Zuckerberg Originally published February 7, 2014 at 12:05 PM | Page modified February 7, 2014 at 5:59 PM Share: 40 years after Boldt, the fight goes Recommend on over fewer and fewer fish 116 Hawk Heaven: The Road to the Seahawks' First Super Bowl Victory. Our respective “share” of the state’s salmon has long been Comments (23) Commemorative book capturing the 2013 season. dictated by an infamous, split-the-baby formula established by E-mail article Print federal judge George Hugo Boldt. His decision was one of the most spectacular plot twists in the history of U.S. resource management. By Ron Judd Seattle Times staff reporter NUMB IS your enemy. It is useful, yes, as a short- PREV 1 of 8 NEXT term masker of pain. But in a crisis, it can put you in the drink. The point was driven home one recent morning as I stood alone, knee-deep in the Nooksack River, casting a jig into the icy waters flowing from the glacial shoulders of Mount Baker. It was late November 2013, and I was engaging in my annual Northwest-native-white-guy rite, my “One Lousy Chum” Puget Sound subsistence- fishery test.