CHAPTER 4 the Second Violin Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Preface and Acknowledgments

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is the extended form of six public lectures delivered in the Ernest Bloch Lecture Series from September 18 to October 23, 1989, in the Department of Music at the University of California at Berkeley. To my regret, the presentation of this expanded version, which for the most part I had finished by the end of 1992, is somewhat overdue, but not without good reason. For an American publication I found that I could not help but produce, if I may say so, a magnum opus, a summary of three decades of Bartók studies, thereby offering grateful, if belated, thanks to the University of California and to my colleagues and students at Berkeley. It was proba- bly the happiest time of my life: I had the honor not only of presenting the music of Béla Bartók but also, at a turning point in Bartók studies, of outlining the tasks awaiting future research on his oeuvre before the most resonant, expert audience I have ever met outside of my country, Hungary—the homeland of Bartók. Coming half a century after the death of the composer, this is the first book dedicated to the study of Bartók's compositional process to be based on the com- plete existing primary source material. Therefore, a great many things need to be accomplished simultaneously: a description of the sources (chapter 3) as well as the first reliable list of manuscripts (in the appendix); an extensive discussion of Bar- tók's sketches and drafts (chapters 4 and 7); an introduction to auxiliary research fields as for instance in paper studies (chapter 6). -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

Bluebeard's Castle

LSO Live Bartók Bluebeard’s Caslte Valery Gergiev Elena Zhidkova Sir Willard White London Symphony Orchestra Béla Bartók (1881–1945) Page Index Bluebeard’s Castle (1911, rev 1912, 1918 and 1921) 3 English notes Valery Gergiev conductor 4 French notes Elena Zhidkova mezzo-soprano (Judith) 5 German notes Sir Willard White bass-baritone (Bluebeard) 6 Opera synopsis London Symphony Orchestra 7 Composer biography 8 Text 17 Conductor biography 1 Prologue and Introduction 15’22’’ 18 Artist biographies 2 First Door: Bluebeard’s Torture Chamber 4’19’’ 20 Orchestra personnel list 3 Second Door: The Armoury 4’16’’ 4 Third Door: The Treasury 2’14’’ 21 LSO biography 5 Fourth Door: The Garden 4’31’’ 6 Fifth Door: Bluebeard’s Vast and Beautiful Kingdom 6’05’’ 7 Sixth Door: The Lake of Tears 13’30’’ 8 Seventh Door: Bluebeard’s Wives 8’29’’ Total Time 58’53’’ Recorded live 27 and 29 January 2009 at the Barbican, London James Mallinson producer Danieli Quilleri casting consultant Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Neil Hutchinson and Jonathan Stokes for Classic Sound Ltd balance engineers Ian Watson and Jenni Whiteside for Classic Sound Ltd audio editors Includes multi-channel 5.1 and stereo mixes. Published by Universal Edition AG © 2009 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK P 2009 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK 2 Alberto Venzago Béla Bartók (1881–1945) already been on several collecting expeditions; For all its qualities and near perfection of last conceals the three wives whom Judith Bluebeard’s Castle (1911, rev 1912, Balázs’s deliberate intent to evoke the strength outline, Bluebeard’s Castle is an early work. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

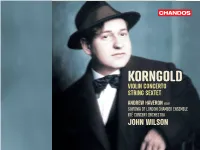

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

CD 1 Total Time 58:45

4.K CD 1 Total Time 58:45 Out of Doors • Im Freien • Szabadban Sz. 81 / BB 89 (1926) 15:44 3 Burlesques • 3 Burlesken • 3 Burleszk op. 8c / Sz. 47 / BB 55 7:29 Vol. 1 bs 01. Quarrel • Zänkerei. Presto (1908) 2:13 1 01. With Drums and Pipes • Mit Trommeln und Pfeifen. Pesante 2:00 bt 02. Slightly tipsy • Etwas angeheitert. Allegretto (1911) 2:47 2 02. Barcarolla. Andante 2:20 bu 03. Molto vivo, capriccioso (1910) 2:29 3 03. Musettes. Moderato 3:11 Vol. 2 4 04. The Night’s Music • Klänge der Nacht. Lento 6:13 Petite Suite • Kleine Suite • Kis szvit Sz. 105 / BB 113 (1936) 7:04 5 05. The Chase • Hetzjagd. Presto 2:00 cl 01. Slow Tune • Getragener Gesang. Lento, poco rubato 2:07 cm 02. Walachian Dance • Tanz aus der Walachei. Allegro giocoso 0:52 cn 03. Whirling Dance • Drehtanz. Allegro 0:54 10 Easy Piano Pieces • 10 leichte Klavierstücke • co 04. Quasi Pizzicato. Allegretto 1:08 10 Könnyu zongoradarab Sz. 39 / BB 51 (1908) 17:37 cp 05. Ruthenian Dance • Kleinrussisch. Allegretto 1:01 6 Dedication • Widmung 3:51 cq 06. Bagpipe • Sackpfeife. Allegro molto 1:02 7 01. Peasant Song • Bauernlied. Allegro moderato 1:05 8 02. A tortuous struggle • Qualvolles Ringen. Lento 1:41 9 03. Slovak Boys’ Dance • Tanz der Slowaken. Allegro 0:56 4 Dirges • 4 Klagelieder • 4 Siratóének bl 04. Sostenuto 1:15 op. 9a / Sz. 45 / BB 58 (1909/10) 10:37 bm 05. Evening in Transylvania • Abend auf dem Lande. Lento rubato 2:00 cr 01. -

Student Achievements 2019 - 2020

Student Achievements 2019 - 2020 SUMMER 2020 8.20 Academy cellist Jan Vargas-Nedvetsky was named winner of the Chicago Chamber Music Festival 6th Annual Concerto Competition for pianists and string players. The winners will be invited to perform with the Northeastern Illinois University Orchestra conducted by Dr. Benjamin Firer during the ‘20 - ‘21 Academic Year. * CCMF Concerto Competition is open to pre-college students only. Perform with NEIU Orchestra during the ‘20 - ‘21 season. • Receive written feedback from a panel of three renowned orchestra conductors • ONE private lesson with CCMF’s faculty* • ONE private meeting with conductor for valuable insight into playing as a soloist with an orchestra • Access to CCMF Special Topic Seminars Pianist Clara Zhang was the winner of the 2018 Concerto Competition. 2020 Chicago International Music Competition 8.20 Congratulations to members of PRIMAVERA AND DASANI ensembles…. tying for the Grand Prize at the 2020 Chicago International Music Competition. More than 400 musicians in 22 countries applied to the virtual competition. GRAND PRIZES DIVISION II—Amateur Division 1st Prize—Trio Primavera coached by Rodolfo Vieira and Mark George. (US): Jan Vargas Nedvetsky / Esme Arias-Kim / Yerin Yang Tied with Dasani String Quartet coached by Mathias Tacke. (US): Isabella Brown/ Katya Moeller/ Zechariah Mo/ Brandon Cheng 2nd Prize—Not Awarded 3rd Prize—Brian Lin (US) In addition, the Academy had winners in the Professional Young Artist II Division. Isabella Brown was awarded first prize, and Katya Moeller second prize, in the Professional Young Artist II Division. Congratulations to everyone for high achievements in a distinguished competition. 7.1.20 - Träumerei Project: Timeless Tribute Video With no end of year orchestra concert, no last day to say goodbye, and no graduation ceremony for the seniors, the Academy Class of 2019-2020, in their homes across four states, created a Time Capsule Video to honor their year together. -

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto”

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto” I believe that one of the most rewarding aspects of life is exploring and discovering the magic and mysteries held within our universe. For a composer this thrill often takes place in the writing of a concerto…it is the exploration of an instrument’s world, a journey of the imagination, confronting and stretching an instrument’s limits, and discovering a particular performer’s gifts. The first movement of this concerto, written for the violinist, Hilary Hahn, carries a somewhat enigmatic title of “1726”. This number represents an important aspect of such a journey of discovery, for both the composer and the soloist. 1726 happens to be the street address of The Curtis Institute of Music, where I first met Hilary as a student in my 20th Century Music Class. An exceptional student, Hilary devoured the information in the class and was always open to exploring and discovering new musical languages and styles. As Curtis was also a primary training ground for me as a young composer, it seemed an appropriate tribute. To tie into this title, I make extensive use the intervals of unisons, 7ths, and 2nds, throughout this movement. The excitement of the first movement’s intensity certainly deserves the calm and pensive relaxation of the 2nd movement. This title, “Chaconni”, comes from the word “chaconne”. A chaconne is a chord progression that repeats throughout a section of music. In this particular case, there are several chaconnes, which create the stage for a dialog between the soloist and various members of the orchestra. The beauty of the violin’s tone and the artist’s gifts are on display here. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Erwartung (Expectation), from Vier Lieder (Four Songs), Op. 2, No. 1 Erwartung, Monodrama in One Act, Op. 17 Arnold Schoenberg rnold Schoenberg spent the summer In any case, her libretto did serve as the ba- A of 1909 in the Lower Austrian town of sis for Schoenberg’s Erwartung, a monodrama Steinakirchen, ostensibly on vacation. In in which a single character, a woman, wanders fact, he kept busy composing, and during through a forest searching for her lover, who that summer he not only wrote his mono- has deceived her, finally stumbling across his drama Erwartung (Expectation) but also murdered, still-bleeding corpse. Schoenberg, completed his Five Orchestra Pieces (Op. however, removed from Pappenheim’s libret- 16) and the third of his Three Piano Pieces to language that suggested that the woman (Op. 11) — landmark works all. Devotees sur- rounded him, including the composer Alex- In Short ander von Zemlinsky, who had become his brother-in-law when Schoenberg married Born: September 13, 1874, in Vienna, Austria Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde in 1901. Also Died: July 13, 1951, in Los Angeles, California passing through was Marie Pappenheim, Works composed and premiered: the song a published poet who had just graduated Erwartung, to a text by Richard Dehmel, was from medical school. Although her special- premiered August 9, 1899; premiered December 1, ty was dermatology, she was well versed in 1901, in Vienna, by tenor Walter Pieau with the recent advances in psychology proposed pianist Alexander von Zemlinsky. -

VIOLIN J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in a Minor Violin Concerto No

VIOLIN HARP J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor DEBUSSY Danses Sacree et Profane (in entirety) Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. 4, No. 6 Romance No. 2 in F Major MOZART Concerto for Flute and Harp in C Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor RAVEL Introduction and Allegro HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major FLUTE LALO Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor GRIFFES Poem MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor HANSON Serenade for Flute MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 MOZART Flute Concerto No. 1 in G Major SAINT-SAËNS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso Flute Concerto No. 2 in D Major Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor TELEMANN Suite in A Minor SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin & Strings VIVALDI All flute concerti (Op 10, Nos. 1–6) VIVALDI The Four Seasons WIENIAWSKI Violin Concerto No. 1 in F# Minor PICCOLO Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor VIVALDI Piccolo Concerto in C Major, Op. 44, No. 11 Piccolo Concerto in A Minor VIOLA HANDEL Viola Concerto in B Minor OBOE HINDEMITH Trauermusik ALBINONI Oboe Concerto in Bb Major, Op. 7, No. 3 MOZART Sinfonia Concertante in Eb Major Oboe Concerto in D Minor, Op. 9, No. 2 TELEMANN Viola Concerto in G Major J.S. BACH Concerto for Oboe and Violin HAYDN Oboe Concerto in C Major VIOLONCELLO MOZART Oboe Concerto in C Major BOCCHERINI All cello concerti HAYDN Cello Concerto No. -

Juilliard String Quartet

SoNoKLECT '06-'07 A Concert Series of Modern Music TERRY VosBEIN, DIRECTOR Juilliard String Quartet The Complete Bart6k Quartets WILSON HALL LENFEST CENTER FOR 'IHE ARTS WASHINGTON AND LEE UNIVERSITY 25 & 26 MAY 2007 8:30 P.M. FRIDAY NI GHT First String Quartet , Op. 7, Sz . 40 (1908) Lento Allegretto Int rod uzione: allegro Allegro vivace pr esto Third String Quartet, Sz. 85 (1927) Prim a parte- Moderat o Second a par te- Allegro Recapitul azione della prim a part e: Mode rato-a ttacca Cod a: Allegro molto - INTERMISSION - Fifth String Quartet, Sz. 102 (1934) Allegro Ad agio rnolto Scherzo: Alla bulga rese- Vivace And ante Finale: Allegro vivace 2 SATURDAY NIGHT Second String Quartet, Op. 17, Sz. 67 (1915-17) Moderato Allegro molto capriccioso Lento Fourth String Quartet, Sz. 91 (1928) Allegro Prestissimo, con sordino Non troppo lento Allegretto pizzicato Allegro molto - INTERMISSION - Sixth String Quartet (1939) Mesto: Piu mosso, pesante-Vivace Mes to-Marcia Mesto: Burletta-Moderato Mesto 3 Bart6k: A Juilliard Quartet Legacy Celebrati ng its sixtieth ann iversary, the Juilli ard String Qu artet re-creates a se minal moment in its history: the first cycle of the six Bart6k quart ets to be perfo rmed in the United States. Seven performances of the compl ete set across the coun try and in Japan dur ing the anni versary seas on, 2006-07, wi ll recall the landmark 1948 premiere at Tanglewoo d. The Bart6k cycle is one of wha t violist Samu el Rhodes, the ensemble's senior member, describes as "common threads that have been supr emely important to the Juilliard Strin g Qu artet." These long-standing interes ts also include the Beethoven quar tets; commissioning important contemp orary compo sers, mo stly Ameri can, to extend the quart et repert oire and tradition ; and a stron g commitm ent to teaching, both chamb er mu sic and the players' ind ividual instrum ents.