Religious Identity of Saraks: Problems and Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Lf?S> "Msftjt'- -^Y^ - Jr* ^ AMBODHI

/ ARl'BftLY *fl^ ) \rf 13 ,1984 MARCH, >I98S Kos. 1-4 ' : iSH 0^ -'X'^' lf?S> "msftJt'- -^y^ - Jr* ^ AMBODHI ARTERLY ) APRIL 1984 MARCH 1985 13 Nos. 1-4 |>RS iUKH MALVANIA ; BETAI SSHASTRI L: D. INSTITUTE OF INDOtOGY, AHMBDABAD-9 : Editors : . Pt, D. D. Malvania Dr. R. S Betai Dr. Y. S. Shastri Board of Experts Pt. D. D. Malvania Dr. H. C. Bhayani Dr. E. A. Solomon Dr. M. A. Dhaky Dr. R. N. Mehta Dr. K. R. Chandra Dr. J. C. Sikdar Dr. R. S. Betai Dr. Y. S. Shastri Contents Refutatiou of Advaita Vedanta in Major Jain Works 1-13 Yajneshwar S. Shastri Unpublished Inscription of Rang Sariga 15 Raghvcndra Manohar Ksvyabandha or Vakyavinyssa 17-23 R. S. Betai Conception of Maya (illusion) In Asanga's Vijnanavada Buddhism 25-34 Y. S, Shastri Bhatti as Quoted in the Durghatavrtti 35-56 Nilanjana S. Shah 'Kasirsja' of Bhasa An Appraisal 57-72 Sudarshan Kumar Sharma Buddhism Vs. Manusmrti 73-78 Jaya R. Betai & Ramesh S. Betai - Avidyg Its Agraya and Visaya 79-99 E. A. Solomon - Vardhaaltna S'uri's Apabhra-m^a Metres 101-109 H. G, Bhayani and Origin Development of Jaina Sangha 111-119 /. C. Sikdar Rasa and its Pleasurable Nature 121-134 V. M. Kulkarni '-HRl M'x-MV >H'4H MM-U Review 63-80 REFUTATION OF ADVAITA VEDANTA IN MAJOR JAINA WORKS* Yajneshwar S. Shastri of Indian History philosophy tells us that all the systems of Indian Philosophy developed in the atmosphere of freedom of thought. There was a tradition in Indian Philosophical platform to present opponent's-, view first known as the Purvapaksa (prior view) and then establishment of one/s own view by refuting opponent's star.d point known as the Uttarapaksa or Siddhanta (conclusion). -

Assaying & Hallmarking Centres in ERO –

Assaying & Hallmarking Centres in ERO – 142 EASTERN REGION- 142 WEST BENGAL – 86 ODISHA - 16 JHARKHAND - 7 BIHAR -22 SIKKIM- 0 CHHATTISGARH – 6 ARUNACHAL PRADESH - 0 ASSAM - 4 NAGALAND - 0 MEGHALAYA - 0 MANIPUR - 0 TRIPURA - 1 MIZORAM - 0 EASTERN REGION- 142 WEST BENGAL – 86 1 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700557 Mr. HARSHAD OPERAT AJMERA IVE Validity: 14/09/2019 C.E.O Tel:9830042105 Fax: 33-30527872 M/s J.J Hallmarking Centre Email: Savitri Tower, 4th Floor, Flat-4A, 3A, Dr. Martin Luther King jjgoldhouse@rediff Sarani, Kolkata-700017 mail.com CPTC qualified centre 2 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700015 Mr. Abhijit Bhattacharjee – Validity: 21.04.2021 Senior Manager Fax: 033 – 40004934 M/s Ace Hallmarking Services Pvt Ltd Operative Tel : 033 – P -24A , Nanigopal Roy chowdhury Avenue , Kolkata – 700014 64513568 / 40004934 Email: Recognized also for Silver Hallmarking acehallmarking@vsn yes l.net 3 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700564 Mr. Prakash Operativ Jagtap, CEO e Validity: 25.10.2019 Mob: 9830142337 Fax: M/s Sidhi Vinayak Hallmarking Centre, Email: st 6, Hanspukur First Lane, 1 Floor, svhalmarking@yaho o.com Kolkata – 700007 4 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHMC/R-700510 Smt. Baijayanti Operative Validity: 03/03/2021 Chowdhury Proprietor A.J. Hallmarking Centre, Tel : 033- 23/39 Gariahat Road 24604402 Kolkata- 700 029 Email: ajhallmarking @gmail.com 5 Recognition No.: ERO/ RAHC/R-700511 Mr. Sandeep S. Operative Validity: 29/06/2021 Chavan, Partner Tel : 03324406297 M/s Rahul Hallmarking centre nd Mob: 9831445388 11 Fern Road, 2 Floor, Email: rahul_hallma Kolkata- 700 019 [email protected] CPTC qualified centre 6 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700518 Mr. -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

Full Text (PDF)

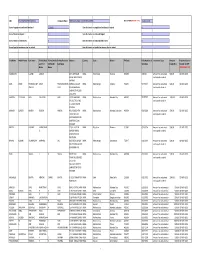

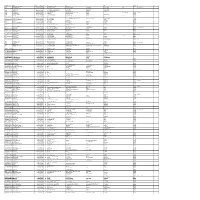

1_10_2009.qxp 18.6.2010 14:00 Stránka 95 • XLVII/1–2 • pp. 95–106 • 2009 SUDIP DATTA BANIK, RAJ KUMAR BARMAN, SHRABANTI MAITY, TANWI SUKUL, VIVEKANANDA ROY ETHNIC VARIATION IN ANTHROPOMETRIC CHARACTERISTICS AND NUTRITIONAL STATUS – A COMPARATIVE STUDY AMONG ADULT MALE ORAONS AND SARAKS OF RANCHI DISTRICT, JHARKHAND, INDIA ABSTRACT: A cross-sectional study was undertaken to investigate the ethnic variation and age-related changes in anthropometric characteristics and nutritional status among the adult males (18 years and above) of two endogamous populations, the Oraon tribe (n=290), and the Saraks (n=158), a comparatively less known caste group in the Ranchi District of the state of Jharkhand in India. The anthropometric characteristics (stature, body weight, mid-upper arm circumference or MUAC, waist circumference and hip circumference), derived index (body mass index or BMI) and ratio (waist-hip ratio or WHR) were categorized in three different age groups (18–39 years, 40–59 years and 60 years and above). Significant differences (p<0.0001) were observed (measured by student t-test) in mean values of anthropometric variables viz. body weight, BMI and hip circumference between the two studied samples. However, results displayed no significant difference in stature and a moderately significant difference in WHR (p<0.01) between the two sections. This particular investigation recorded high frequency of undernutrition (chronic energy deficiency or CED 53.10% among the Oraons and 27.85% among the Saraks), as measured by the WHO (1995) recommended values of BMI for the adults. It has been noted that 38.28% of the adult Oraons and 20.89% of the adult Saraks suffer from undernutrition when the nutritional status of the two communities is evaluated by the standard cut-off points of MUAC. -

CIN Company Name

CINL92199MH1995PLC084610 Company Name HINDUJA GLOBAL SOLUTIONS LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD‐MON‐YYYY) 10‐AUG‐2013 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 2113395 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husba Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First nd Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD‐MON‐YYYY) KUNDUKURI LASHMI LASHMI 864 18TH MAIN INDIA Tamil Nadu Chennai 600000 000218 Amount for unclaimed 500.00 02‐NOV‐2015 ROAD ANNA NAGAR and unpaid dividend MADRAS UMIL LEASE FINANCECOMP LEASE FINANCECOMPAN MANGAL KALASH INDIA West Bengal Kolkata 700071 00103021 Amount for unclaimed 500.00 02‐NOV‐2015 ANYLTD YLTD 2A SHAKESPEARE and unpaid dividend SARANI 5TH FLOOR CALCUTTA HANSRAJ CHHOGAJI JAIN CHHOGAJI JAIN 19/20 MAHAJAN INDIA Maharashtra Mumbai City 400002 00103501 Amount for unclaimed 1000.00 02‐NOV‐2015 GALI 1ST FLR R NO and unpaid dividend 17 ZAVERI BAZAR BOMBAY AVINASH SURESH RAHEJA SURESH RAHEJA 401 PICASSO 4TH INDIA Maharashtra Mumbai Suburban 400054 00106330 Amount for unclaimed 500.00 02‐NOV‐2015 FLOOR 94 C OFF and unpaid dividend INDRANARAYAN RD SANTACRUZ (W) MUMBAI BRIJESH JHURANI KHANCHAND 27/81 JHULELAL INDIA Rajasthan Bhilwara 311001 00109754 Amount -

List Mandi Supervisor.Xlsx

List of Unsuccessful Candidates for the post of Mandi Supervisor, Cat. No. 27, against Adv. No 14/2007, dated 09.11.2007 Roll Name Father Name Caste Address District No 1 MONIKA BUDGUJAR DARYAO SINGH SC S-1 PUBLIC HEALTH COLONY ROHTAK 2 RISHIPAL RAMKANWAR GENERAL VPO KHIDWALI PANA THOI ROHTAK 3 SATYAVEER JASWANT SINGH BCB VPO DUNGERWAS REWARI 4 AJIT LAYAK RAM GENERAL VPO NONOND ROHTAK 5 RAVI SHANKER RANGA SHILAK RAM SC VPO TITOLI ROHTAK 6 SANDEEP KUMAR CHANDER BHAN GENERAL HNO C-71/22 KISHAN PURA ROHTAK 7 SURJEET SINGH GURSAHIB SINGH GENERAL VILL MANCHURI PO SHEKHUPURA TEH ASSANDH KARNAL 8 PAWAN KUMAR SAHU DAYA RAM SAHU GENERAL TOWN JALAUN HARIPURA MOHALLA JALAUN 9 SUSHMA DEVI RAM SARUP GENERAL HNO 29-B RAILWAY COLONY JAGADHRI WORKSHOP YAMUNANAGAR 10 ANITA KUMARI GULAB SINGH GENERAL HNO 467/22 DURGA COLONY ROHTAK 11 DHARMENDER AMAR NATH BCA HNO 2/319 ARYA NAGAR SONEPAT 12 ASHOK KUMAR JAI NARAIN GENERAL VPO BOHAR ROHTAK 13 KAPIL NEER SINGH GENERAL VPO MAKRAULI KHURD TEH ROHTAK ROHTAK 14 SACHIN RAJENDER SINGH GENERAL HNO 1835-A/30 CHOTTU RAM COLONY NEAR KANHERI ROAD ROHTAK 15 RAVINDER KUMAR PRITAM SINGH GENERAL VPO SILANA SONEPAT 16 SAWAL RAM DAYAMA JHABBU RAM DAYAMA SC MOH DHOBI GHAT WNO-9 BAWAL REWARI 17 ANIL KUMAR DILBAG SINGH GENERAL VPO BHALI ANANDPUR ROHTAK 18 AMIT KUMAR PREM CHAND JAIN GENERAL HNO 446 SEC 7 URBAN ESTATE AMBALA 19 BHARAT SINGH MORDHWAJ BCB VPO RAMGARH REWARI 20 VISHAL SHARMA S K SHARMA GENERAL HNO 27 KABIR NAGAR MAHESH NAGAR AMBALA CANTT AMBALA 21 SANDEEP SINGH SUBE SINGH GENERAL VPO JATAL PANIPAT 22 HARI OM BALJEET -

Parental Attitude of Sarak Community Towards Girls Education at Higher Stage in West Bengal

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 1 January 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 PARENTAL ATTITUDE OF SARAK COMMUNITY TOWARDS GIRLS EDUCATION AT HIGHER STAGE IN WEST BENGAL Abhisek Panda, Aditya Majee B.Ed Students , Regional Institute of Education, Bhubaneswar, Odisha Abstract: In this modern society, girls are subjected to all of discrimination especially in educational field because of the stereotype thinking. When a pilot study was done by the researchers in a backward district (Purulia) of West Bengal, it was found that majority of Sarak girls were dropout and parents are not interested to educate their girls at higher education level due to different problems. so, the objectives of the study was to know the views of parents about the education and reasons of the dropout of girls according to their education and economic status and status of the girl child. Here investigators purposively selected 200 samples for data collection by self made questionnaire. The study indicates some significant results on these problems. Keywords: Sarak Community, Purulia District, Girls Education I. INTRODUCTION Indian constitution give guarantee that everyone has right to access education whether boys or girls. In this 21st century when whole world trying to achieve the sustainable development goal, gender equality which is the fifth goal of among the seventeen goals still become create a challenging situation in Indian education system. We talk about feminist society, but in our male dominate society still the women’s are deprived. When the human development index indicate that education is an indicator of a country’s development then in the question of girl’s education it lost its expectancies.Unless educated women, a country cannot progress. -

Volume : 103 Issue No. : 103 Month : February, 2009

Volume : 103 Issue No. : 103 Month : February, 2009 Your worst days are never so bad, that you are beyond the reach of God's grace. Your good days are never so good that you are beyond the need of God's grace. Hands that help are holier than lips that pray. TEMPLES COURT PROCEEDINGS ABOUT RISHABH DEV TO BE CONDUCTED BY JUSTICE S. B. SINHA The Supreme Court of India has constituted a bench on the two writ petitions to look into the raging controversy about the control over Shri Rishabh Dev temple near Udaipur in Rajasthan. The bench headed by the Chief Justice Shri K. G. Balakrishan had earlier issued notices to the State Government and others on the 14th may, 2007. The newly constituted bench will now consider the public interest petitions, which have requested that the notifications issued on the 20th January, 07 by the Assistant Commissioner, Devasthan Deprtment, Government of Rajasthan may be withdrawn, in which proposals were invited from the interested persons to form a management committee for the control of Rishabh Dev temple. As is well known, the issue is about the controversy, whether it is a jain temple or Hindu temple. The Raj. High Court had earlier given a decision that it is a Jain temple. After considering the whole matter, the Supreme Court had also agreed that it was a Jain temple. The apex court had later asked the Devasthan Department, State Government and the concerned parties as to why the matter be not reconsidered and why a district Judge be not appointed to enquire into the whole matter once again. -

Mgl-Di420- List of Unpaid Shareholders As on 31.12

FOLIO-DEMAT ID NAME NETDIV DWNO MICR AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 CITY PINCOD JH1 JH2 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 220000.00 204000027 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2200.00 204000030 3 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 2200.00 204000031 4 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 001004 KARTHIKEYAN P.K. 2200.00 204000033 6 PANIKKASSERY HOUSE, THRIPRAYAR POST NATTIKA TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 002769 RAMLATH V E 2200.00 204000037 10 ELLATHPARAMBIL HOUSE NATTIKA BEACH P O THRISSUR KERALA 003124 VENUGOPAL M R 2200.00 204000041 14 MOOTHEDATH (H) SAWMILL ROAD KOORVENCHERY THRISSUR GEETHADEVI M V 000000 RISHI M.V. 003292 SURENDARAN K K 2068.00 204000043 16 KOOTTALA (H) PO KOOKKENCHERY THRISSUR 000000 003442 POOKOOYA THANGAL 2068.00 204000045 18 MECHITHODATHIL HOUSE VELLORE PO POOKOTTOR MALAPPURAM 000000 003445 CHINNAN P P 2200.00 204000046 19 PARAVALLAPPIL HOUSE KUNNAMKULAM THRISSUR PETER P C 000000 IN30177410163576 Rukaiya Kirit Joshi 2695.00 204000064 37 303 Anand Shradhanand Road Vile Parle East Mumbai 400057 001012 SHARAVATHY C.H. 2200.00 204000065 38 W/O H.L.SITARAMAN, 15/2A,NAV MUNJAL NAGAR,HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY CHEMBUR, MUMBAI 400089 IN30028010510303 JAIN SANJAY KHEMCHAND 1815.00 204000068 41 185 RAVIWAR PETH SATARA 415002 IN30066910186257 B MURALIDHAR 1952.50 204000075 48 D NO 13-56/A KANKIPADU KRISHNA DIST 521151 000697 AMALA S. 4400.00 204000081 54 36 CAR STREET SOWRIPALAYAM COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641028 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN 22000.00 204000082 55 NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 1202990005855228 SHEJI MATHEW KURIAKOSE 3135.00 204000083 56 658 Ozhukayil House P O Taliparamba Pushpagiri Dt Kannur 670141 003506 KAMALA K 2200.00 204000091 64 SRUTHY NIVAS ALACHANCODE CHITTUR COLLEGE P O CHITTUR PALAKKAD 678104 000637 MURALEEDHARAN T.R. -

Assaying & Hallmarking Centres in ERO –

Assaying & Hallmarking Centres in ERO – 138 EASTERN REGION- 138 WEST BENGAL – 82 ODISHA - 16 JHARKHAND - 7 BIHAR -22 SIKKIM- 0 CHHATTISGARH – 6 ARUNACHAL PRADESH - 0 ASSAM - 4 NAGALAND - 0 MEGHALAYA - 0 MANIPUR - 0 TRIPURA - 1 MIZORAM - 0 EASTERN REGION- 138 WEST BENGAL – 82 1 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700557 Mr. HARSHAD OPERAT AJMERA IVE Validity: 14/09/2019 C.E.O Tel:9830042105 Fax: 33-30527872 M/s J.J Hallmarking Centre Email: Savitri Tower, 4th Floor, Flat-4A, 3A, Dr. Martin Luther King jjgoldhouse@rediff Sarani, Kolkata-700017 mail.com CPTC qualified centre 2 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700015 Mr. Abhijit Bhattacharjee – Validity: 21.04.2021 Senior Manager Fax: 033 – 40004934 M/s Ace Hallmarking Services Pvt Ltd Operative Tel : 033 – P -24A , Nanigopal Roy chowdhury Avenue , Kolkata – 700014 64513568 / 40004934 Email: Recognized also for Silver Hallmarking acehallmarking@vsn l.net 3 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700564 Mr. Prakash Operativ Jagtap, CEO e Validity: 25.10.2019 Mob: 9830142337 Fax: M/s Sidhi Vinayak Hallmarking Centre, Email: st 6, Hanspukur First Lane, 1 Floor, svhalmarking@yaho o.com Kolkata – 700007 4 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHMC/R-700510 Smt. Baijayanti Operative Validity: 03/03/2021 Chowdhury Proprietor A.J. Hallmarking Centre, Tel : 033- 23/39 Gariahat Road 24604402 Kolkata- 700 029 Email: ajhallmarking @gmail.com 5 Recognition No.: ERO/ RAHC/R-700511 Mr. Sandeep S. Operative Validity: 29/06/2021 Chavan, Partner Tel : 03324406297 M/s Rahul Hallmarking centre Mob: 9831445388 nd 11 Fern Road, 2 Floor, Email: rahul_hallma Kolkata- 700 019 [email protected] CPTC qualified centre 6 Recognition No.: ERO/RAHC/R-700518 Mr. -

Non Pesa Merit List Pune 2018.Pdf

Earth Part- Handica Ex- quak Non- Project time Sportsm Marks Sl no Registration No Candidate Name Address DOB Gender Category pped service e creamy affected emplo an obtained type men affec layer yee ted AT POST WAFALE WAFALE WAFALE SOLAPUR 1 AGRI_KS_0051316 GAYATRI RAMESHWAR CHAVAN 1993-10-01 FEMALE GENERAL TRUE 161.86 MAHARASHTRA Ap-Awsari Kh Awsari Kh Awsari Kh PUNE 2 AGRI_KS_0057221 Chhaya Tukaram Shinde 1990-07-21 FEMALE GENERAL TRUE 157.36 MAHARASHTRA At post -boratwadi , tal-indapur ,pune At post-boratwadi 3 AGRI_KS_0060820 Yogesh Bharat Phadatare 1995-04-24 MALE GENERAL 156.7 Boratwadi PUNE MAHARASHTRA AT DEOKARWADI POST DAHITANE DAHITANE PUNE 4 AGRI_KS_0025306 MAHESH MANSING SHITOLE 1986-06-28 MALE GENERAL 156.35 MAHARASHTRA 5 AGRI_KS_0049887 PRAVIN ROHIDAS MANE KOTHALE MANEWADI PIMPRI SOLAPUR MAHARASHTRA 1987-06-01 MALE NT-C TRUE 155.67 At post -thergaon tal- karjat thergaon AHMEDNAGAR 6 AGRI_KS_0023147 ASHWINI SANDIP JADHAV 1994-06-06 FEMALE OBC TRUE 155.67 MAHARASHTRA 7 AGRI_KS_0061390 sonali sambhaji gadekar Shinde galli Kusalamb SOLAPUR MAHARASHTRA 1994-05-20 FEMALE GENERAL TRUE 154.64 AT BANEGAON POST KALGAON POST KALGAON 8 AGRI_KS_0030914 SHIVPRASAD SAMBHAJI BHOSLE 1988-08-16 MALE GENERAL 154.31 PARBHANI MAHARASHTRA RAJESH NIWAS BALEWADI POST KARANJE SOLAPUR 9 AGRI_KS_0023238 RAJESH SUBHASH NALAWADE 1991-09-02 MALE GENERAL 154.31 MAHARASHTRA MATOSHRI NIVAS AT POST NEWARE NEWARE SOLAPUR 10 AGRI_KS_0012985 SUNIL PANDURANG VYAVAHARE 1989-03-04 MALE GENERAL 154.08 MAHARASHTRA AT -BHAVADI POST- HIRADGAON SHRIGONDA 11 AGRI_KS_0054738