Sources of Party System Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

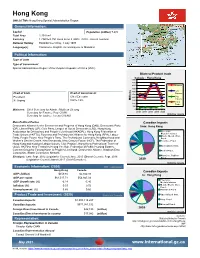

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

Short Report

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID FORMED COLLECTION FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS, 1901-2014 PRINTED AUSTRALIANA AUGUST 2017 The Library has been actively collecting Federal election campaign ephemera for many years. ACCESS The Australian Federal Elections ephemera may requested by eCall-slip and used through the Library’s Special Collections Reading Room. Readers are able to request files relating to a specific election year. Please note: . 1901-1913 election material all in one box . 1914-1917 election material all in one box OTHER COLLECTIONS See also the collection of related broadsides and posters, and within the PANDORA archive. See also ‘Referenda’ in the general ephemera run. CONTENT AND ARRANGEMENT OF THE COLLECTION 1901 29-30 March see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period 1903 16 December see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period 1906 12 December see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period 1910 13 April see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labour Party Folder 2. Liberal Party 1913 31 May see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labor Party Folder 2. Liberal Party Folder 3. Other candidates 1914 ― 5 September (double dissolution) see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labor Party Folder 2. Liberal Party 1917 5 May see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. Australian Labor Party Folder 2. National Party Folder 3. Other candidates 1919 13 December see also digitised newspaper reports and coverage from the period Folder 1. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: What Are the Prospects for the Polish Left? Page 1 of 4

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: What are the prospects for the Polish left? Page 1 of 4 What are the prospects for the Polish left? Poland’s communist successor party has seen its opinion poll ratings increase in recent months. This upturn in support came after the revival of debates about the country’s communist past prompted by government legislation affecting the interests of its core electorate. But as Aleks Szczerbiak writes, the party’s leadership has failed to develop any new ideas or initiatives that can attract broader support beyond this declining group of former communist regime beneficiaries and functionaries. Without a political game-changer, the left will remain a marginal actor in Polish politics. Image from a Democratic Left Alliance campaign event ahead of the 2014 European Parliament elections, Credit: Democratic Left Alliance For most of the post-1989 period, the most powerful political and electoral force on the Polish left was the communist successor Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), which governed the country from 1993-97 and 2001-5. However, the Alliance has been in the doldrums since its support collapsed in the 2005 parliamentary election following a series of spectacular high-level corruption scandals. It contested the most recent October 2015 election – won decisively by the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party, the first political grouping in post-communist Poland to secure an outright parliamentary majority – as part of the ‘United Left’ (ZL) electoral coalition in alliance with the ‘Your Movement’ (TR) grouping. The latter was an anti-clerical social liberal party led by controversial businessman Janusz Palikot, which came from nowhere to finish third with just over 10% of the votes in the 2011 election but failed to capitalise on this success and saw its support decline steadily. -

The Public Sector in Hong Kong

THE PUBLIC SECTOR IN HONG KONG IN HONG PUBLIC SECTOR THE THE PUBLIC SECTOR IN HONG KONG his book describes and analyses the role of the public sector in the T often-charged political atmosphere of post-1997 Hong Kong. It discusses THE PUBLIC SECTOR critical constitutional, organisational and policy problems and examines their effects on relationships between government and the people. A concluding chapter suggests some possible means of resolving or minimising the difficulties which have been experienced. IN HONG KONG Ian Scott is Emeritus Professor of Government and Politics at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Public and Social Administration at the City University of Hong Kong. He taught at the University of Hong Kong between 1976 and 1995 and was Chair Professor of Politics and Public Administration between 1990 and 1995. Between 1995 and 2002, he was Chair Professor of Government and Politics at Murdoch University. Over the past twenty-five years, he has written extensively on politics and public administration in Hong Kong. G O V E P O L I C Y Professor Ian Scott’s latest book The Public Sector in Hong Kong provides a systematic analysis of Hong Kong’s state of governance in the post-1997 period Ian Scott R and should be read by government officials, politicians, researchers, students and N general readers who seek a better understanding of the complexities of the city’s M government and politics. E — Professor Anthony B. L. Cheung, President, The Hong Kong Institute of Education; N T Member, Hong Kong SAR Executive Council. -

Folder 14 Poland, Vol. 1

--- ,· . ' - ~~ -----1.- Via Diploma.tic Pouch. v' ./ Mr. Van Arsdale Turner, Acting Asst. Director, Civilian Relief, Insular & Foreign Operations, American Red Crose, National Headquarters, Washington, D.c. Dear Van: Reverting to your letter of March 17 and 9J1l' reply of April Y, on the subject of the copy O!/the current report on the work of the Joint Relief Commission in Poland which you desired to receive, the London Committee of the International Red Cross have now been able to furnish us with copies of the following reports, which please find enclosed herewith: Join{ Relief Commission of the International Red Cross, a~~va, Distribution of medical supplies to.Poland, 11 Comporel S JDent", 1942-1943. v v Joint Relief Commission of the International Red Cross, Geneva,. Med~aments Envois en Pologne 1942-1943. "" -~ The I.R.CoC. inform us that a copy of the report of the Joint Relief Commission in Poland was sent direatiy to you from Geneva on March 1.4. ~"fil:rr~ / William L. Gower, Director of Civilian Re.lief. RW. .• . OFTHi;i rn"iEi~ATIQ~AL RIBD CROSS International Heid Gross Committee - 4, Cours des Bastions1 - PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICE ...;. MEDICAL SUPPLIES i. '' ShipmentR into Poland. Typed on slip '~ttached to this page. In order tlnt ,,'co may oc; Hble to fill in the gaps which are apparent, in thi:c tre1o,tl:c<?, >;7 :ih~~ll oe very grC1.teful if you ~till com~nunicate any additional in !'orma ti on, wi;ich you rrmy possess. un following page, SUMMARY \ Pages1 I. Introductory Note 1 & 2 ,\\ \ II. Resume of Shipments: \ ·\ . -

Now Is the Time to Give Civic Party Its Last Rites

8 | Wednesday, April21, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY COMMENTHK Yang Sheng Now is the time to give Harris’ antics Civic Party its last rites threaten to bring Grenville Cross says the political group has done more harm HKBA down to Hong Kong than any other and its departure is long overdue aul Harris, a former British politician and current chair- man of the Hong Kong Bar Association (HKBA), spouted some uneducated theories that fully exposed his hypo- n November 11, 2020, the the national anthem law, both of which Hong critical self in a recent interview, in which he questioned National People’s Con- Kong was constitutionally obliged to enact. In Pthe legitimacy of the National People’s Congress’ (NPC) decision gress Standing Committee consequence, there was legislative gridlock, to improve Hong Kong’s electoral system, claiming that the vet- (NPCSC) adopted a resolu- with 14 bills and 89 items of subsidiary legisla- ting of candidates by a review committee may violate voter rights tion whereby members of tion being blocked, many a ecting people’s by limiting their choices. However, he failed to mention the fact the Hong Kong Legislative livelihoods. Although the deadlock was fi nally that vetting candidates is a common practice around the world to Council immediately lost Grenville Cross broken on May 18, no thanks to Kwok, his ensure national security or other national interests. Would Paul their seats if, in violation of their oaths of The author is a senior counsel, law professor was an unprecedented move to paralyze the Harris, who served as a councilor of Oxford city in the past, cast and criminal justice analyst, and was previ- o ce, they were deemed to have engaged in Legislative Council, and to prevent it from dis- the same human rights abuse suspicion over the relevant laws of O ously the director of public prosecutions of charging the legislative functions required of various nefarious activities. -

Andrew Jackson

THE JACKSONIAN ERA DEMOCRATS AND WHIGS: THE SECOND PARTY SYSTEM THE “ERA OF GOOD FEELINGS” • James Monroe (1817-1825) was the last Founder to serve as President • Federalist party had been discredited after War of 1812 • Monroe unopposed for reelection in 1820 • Foreign policy triumphs: • Adams-Onís Treaty (1819) settled boundary with Mexico & added Florida • Monroe Doctrine warned Europeans against further colonization in Americas James Monroe, By Gilbert Stuart THE ELECTION OF 1824 & THE SPLIT OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY • “Era of Good Feelings” collapsed under weight of sectional & economic differences • New generation of politicians • Election of 1824 saw Republican party split into factions • Andrew Jackson received plurality of popular & electoral vote • House of Representatives chose John Quincy Adams to be president • Henry Clay became Secretary of State – accused of “corrupt bargain” • John Quincy Adams’ Inaugural Address called in vain for return to unity THE NATIONAL REPUBLICANS (WHIGS) • The leaders: • Henry Clay • John Quincy Adams • Daniel Webster • The followers: • Middle class Henry Clay • Educated • Evangelical • Native-born • Market-oriented John Quincy Adams WHIG ISSUES • Conscience Whigs – abolition, temperance, women’s rights, etc. • Cotton Whigs – internal improvements & protective tariffs to foster economic growth (the “American System”) THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICANS (DEMOCRATS) • The leaders: • Martin Van Buren • Andrew Jackson • John C. Calhoun • The followers: Martin Van Buren • Northern working class & Southern planter aristocracy • Not well-educated • Confessional churches • Immigrants • Locally-oriented John C. Calhoun DEMOCRATIC ISSUES • Limited power for federal government & states’ rights • Opposition to “corrupt” alliance between government & business • Individual freedom from coercion “KING ANDREW” & THE “MONSTER BANK” • Marshall’s decision in McCulloch v. -

The Italian Communist Party 1921--1964: a Profile

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1966 The Italian Communist Party 1921--1964: A profile. Aldo U. Marchini University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Marchini, Aldo U., "The Italian Communist Party 1921--1964: A profile." (1966). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6438. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6438 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript and are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was scanned as received. it This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE ITALIAN COkkUNIST PARTY 1921 - 196A: A PROPILE by ALDO U. -

The Demise of the Second Party System and the Rise of the Republican Party

The Demise Of The Second Party System And The Rise Of The Republican Party Antonio Lovato The Whig Party • 1834-1854 • Led by Henry Clay • A group organized in their opposiHon to Andrew JacKson • They supported the supremacy of Congress over the Presidency. • Had 2 presidents: William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor; both died in office. – John Tyler succeeded Harrison but was expelled from the party and was a firm democrat – Millard Fillmore became president aer Taylor and was the last Whig to hold office The Whig Party ConHnued • JacKson’s victories in 1828 and 1832 destroyed the Naonal Republican Party and allowed for the Whig party to grow. • In 1836 they ran three presidenHal candidates (Daniel Webster, Hugh L. White, and William Henry Harrison) to appeal to the East, South, and West • They pracHcally captured Congress and the White House in 1840 and were poised to become the naon’s dominant party. The Demise of the Whig Party • By the late 1840’s the Whig party began to unravel due to the dispute of slavery. • Millard Fillmore’s enforcement of the fugiHve slave law won the support of the southern Whigs but had alienated anHslavery Whigs. • The Party was destroyed primarily by the quesHon of whether to expand slavery and because Fillmore wasn’t reelected in 1852 the party nominated General Winfield Scoc. • Scoc won favor because he had support from the North and some support from the South in the ElecHon of 1852. • On ElecHon Day, the power of the Whigs significantly decreased due to the fact that they had elected no governors and no president, leaving only control of Tennessee and KentucKy.