Preliminary Assessment Huckleberry Enhancement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mount Hood National Forest Recommendations for Policy Changes

PROTECTING FRESHWATER RESOURCES ON MOUNT HOOD NATIONAL FOREST RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY CHANGES Produced by PACIFIC RIVERS COUNCIL Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mount Hood National Forest Pacific Rivers Council January 2013 Fisherman on the Salmon River Acknowledgements This report was produced by John Persell, in partnership with Bark and made possible by funding from The Bullitt Foundation and The Wilburforce Foundation. Pacific Rivers Council thanks the following for providing relevant data and literature, reviewing drafts of this paper, offering important discussions of issues, and otherwise supporting this project. Alex P. Brown, Bark Dale A. McCullough, Ph.D. Susan Jane Brown Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission Western Environmental Law Center G. Wayne Minshall, Ph.D. Lori Ann Burd, J.D. Professor Emeritus, Idaho State University Dennis Chaney, Friends of Mount Hood Lisa Moscinski, Gifford Pinchot Task Force Matthew Clark Thatch Moyle Patrick Davis Jonathan J. Rhodes, Planeto Azul Hydrology Rock Creek District Improvement Company Amelia Schlusser Richard Fitzgerald Pacific Rivers Council 2011 Legal Intern Pacific Rivers Council 2012 Legal Intern Olivia Schmidt, Bark Chris A. Frissell, Ph.D. Mary Scurlock, J.D. Doug Heiken, Oregon Wild Kimberly Swan Courtney Johnson, Crag Law Center Clackamas River Water Providers Clair Klock Steve Whitney, The Bullitt Foundation Klock Farm, Corbett, Oregon Thomas Wolf, Oregon Council Trout Unlimited Bronwen Wright, J.D. Pacific Rivers Council 317 SW Alder Street, Suite 900 Portland, OR 97204 503.228.3555 | 503.228.3556 fax [email protected] pacificrivers.org Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mt. Hood National Forest: 2 Recommendations for Policy Change Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Part One: Introduction—An Urban Forest 1 Part Two: Watersheds of Mt. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Eg-Or-Index-170722.05.Pdf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Burns Paiute Tribal Reservation G-6 Siletz Reservation B-4 Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Reservation B-3 Umatilla Indian Reservation G-2 Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation H-9,10 Warm Springs Indian Reservation D-3,4 Ankeny National Wildlife Refuge B-4 Basket Slough National Wildlife Refuge B-4 Badger Creek Wilderness D-3 Bear Valley National Wildlife Refuge D-9 9 Menagerie Wilderness C-5 Middle Santiam Wilderness C-4 Mill Creek Wilderness E-4,5 Black Canyon Wilderness F-5 Monument Rock Wilderness G-5 Boulder Creek Wilderness C-7 Mount Hood National Forest C-4 to D-2 Bridge Creek Wilderness E-5 Mount Hood Wilderness D-3 Bull of the Woods Wilderness C,D-4 Mount Jefferson Wilderness D-4,5 Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument C-9,10 Mount Thielsen Wilderness C,D-7 Clackamas Wilderness C-3 to D-4 Mount Washington Wilderness D-5 Cold Springs National Wildlife Refuge F-2 Mountain Lakes Wilderness C-9 Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Newberry National Volcanic Monument D-6 C-2 to E-2 North Fork John Day Wilderness G-3,4 Columbia White Tailed Deer National Wildlife North Fork Umatilla Wilderness G-2 Refuge B-1 Ochoco National Forest E-4 to F-6 Copper Salmon Wilderness A-8 Olallie Scenic Area D-4 Crater Lake National Park C-7,8 Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area C-4 Crooked River National Grassland D-4 to E-5 Opal Creek Wilderness C-4 Cummins Creek Wilderness A,B-5 Oregon Badlands Wilderness D-5 to E-6 Deschutes National Forest C-7 to D-4 Oregon Cascades Recreation Area C,D-7 Diamond Craters Natural Area F-7 to G-8 Oregon -

Public Law 111-11

PUBLIC LAW 111–11—MAR. 30, 2009 123 STAT. 991 Public Law 111–11 111th Congress An Act To designate certain land as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System, to authorize certain programs and activities in the Department of the Mar. 30, 2009 Interior and the Department of Agriculture, and for other purposes. [H.R. 146] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Omnibus Public Land SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. Management Act (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Omnibus of 2009. Public Land Management Act of 2009’’. 16 USC 1 note. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents of this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. TITLE I—ADDITIONS TO THE NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM Subtitle A—Wild Monongahela Wilderness Sec. 1001. Designation of wilderness, Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia. Sec. 1002. Boundary adjustment, Laurel Fork South Wilderness, Monongahela Na tional Forest. Sec. 1003. Monongahela National Forest boundary confirmation. Sec. 1004. Enhanced Trail Opportunities. Subtitle B—Virginia Ridge and Valley Wilderness Sec. 1101. Definitions. Sec. 1102. Designation of additional National Forest System land in Jefferson Na tional Forest as wilderness or a wilderness study area. Sec. 1103. Designation of Kimberling Creek Potential Wilderness Area, Jefferson National Forest, Virginia. Sec. 1104. Seng Mountain and Bear Creek Scenic Areas, Jefferson National Forest, Virginia. Sec. 1105. Trail plan and development. Sec. 1106. Maps and boundary descriptions. Sec. 1107. Effective date. Subtitle C—Mt. Hood Wilderness, Oregon Sec. -

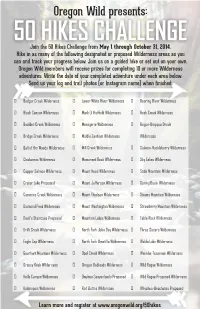

50 HIKES CHALLENGE Join the 50 Hikes Challenge from May 1 Through October 31, 2014

Oregon Wild presents: 50 HIKES CHALLENGE Join the 50 Hikes Challenge from May 1 through October 31, 2014. Hike in as many of the following designated or proposed Wilderness areas as you can and track your progress below. Join us on a guided hike or set out on your own. Oregon Wild members will receive prizes for completing 10 or more Wilderness adventures. Write the date of your completed adventure under each area below. Send us your log and trail photos (or Instagram name) when finished. � Badger Creek Wilderness � Lower White River Wilderness � Roaring River Wilderness � Black Canyon Wilderness � Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness � Rock Creek Wilderness � Boulder Creek Wilderness � Menagerie Wilderness � Rogue-Umpqua Divide � Bridge Creek Wilderness � Middle Santiam Wilderness Wilderness � Bull of the Woods Wilderness � Mill Creek Wilderness � Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness � Clackamas Wilderness � Monument Rock Wilderness � Sky Lakes Wilderness � Copper Salmon Wilderness � Mount Hood Wilderness � Soda Mountain Wilderness � Crater Lake Proposed � Mount Jefferson Wilderness � Spring Basin Wilderness � Cummins Creek Wilderness � Mount Thielsen Wilderness � Steens Mountain Wilderness � Diamond Peak Wilderness � Mount Washington Wilderness � Strawberry Mountain Wilderness � Devil’s Staircase Proposed � Mountain Lakes Wilderness � Table Rock Wilderness � Drift Creek Wilderness � North Fork John Day Wilderness � Three Sisters Wilderness � Eagle Cap Wilderness � North Fork Umatilla Wilderness � Waldo Lake Wilderness � Gearhart Mountain Wilderness � Opal Creek Wilderness � Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness � Grassy Knob Wilderness � Oregon Badlands Wilderness � Wild Rogue Wilderness � Hells Canyon Wilderness � Owyhee Canyonlands Proposed � Wild Rogue Proposed Wilderness � Kalmiopsis Wilderness � Red Buttes Wilderness � Whychus-Deschutes Proposed Learn more and register at www.oregonwild.org/50hikes. -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 10, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) Sec. 1132. Extent of System. § 1110. Liability 1133. Use of wilderness areas. 1134. State and private lands within wilderness (a) United States areas. The United States Government shall not be 1135. Gifts, bequests, and contributions. liable for any act or omission of the Commission 1136. Annual reports to Congress. or of any person employed by, or assigned or de- § 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System tailed to, the Commission. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of (b) Payment; exemption of property from attach- policy; wilderness areas; administration for ment, execution, etc. public use and enjoyment, protection, preser- Any liability of the Commission shall be met vation, and gathering and dissemination of from funds of the Commission to the extent that information; provisions for designation as it is not covered by insurance, or otherwise. wilderness areas Property belonging to the Commission shall be In order to assure that an increasing popu- exempt from attachment, execution, or other lation, accompanied by expanding settlement process for satisfaction of claims, debts, or judg- and growing mechanization, does not occupy ments. and modify all areas within the United States (c) Individual members of Commission and its possessions, leaving no lands designated No liability of the Commission shall be im- for preservation and protection in their natural puted to any member of the Commission solely condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy on the basis that he occupies the position of of the Congress to secure for the American peo- member of the Commission. -

Pacific Northwest Wilderness

pacific northwest wilderness for the greatest good * Throughout this guide we use the term Wilderness with a capital W to signify lands that have been designated by Congress as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System whether we name them specifically or not, as opposed to land that has a wild quality but is not designated or managed as Wilderness. Table of Contents Outfitter/Guides Are Wilderness Partners .................................................3 The Promise of Wilderness ............................................................................4 Wilderness in our Backyard: Pacific Northwest Wilderness ...................7 Wilderness Provides .......................................................................................8 The Wilderness Experience — What’s Different? ......................................9 Wilderness Character ...................................................................................11 Keeping it Wild — Wilderness Management ...........................................13 Fish and Wildlife in Wilderness .................................................................15 Fire and Wilderness ......................................................................................17 Invasive Species and Wilderness ................................................................18 Climate Change and Wilderness ................................................................19 Resources ........................................................................................................21 -

Roaring River Wilderness Air Quality Report, 2012

Roaring River Wilderness Air Quality Report Wilderness ID: 453 Wilderness Name: Roaring River Wilderness Roaring River Wilderness Air Quality Report National Forest: Mount Hood National Forest State: OR Counties: Clackamas General Location: Northern Oregon Cascade Range Acres: 36,768 Thursday, May 17, 2012 Page 1 of 4 Roaring River Wilderness Air Quality Report Wilderness ID: 453 Wilderness Name: Roaring River Wilderness Wilderness Categories Information Specific to this Wilderness Year Established 2009 Establishment Notes Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 Designation Clean Air Act Class 2 Administrative Mount Hood National Forest Unique Landscape Features The largest block of new wilderness designated in 2009 in Oregon is in the Roaring River Valley, a tributary of the Clackamas River. The wilderness area is named after the Roaring River that flows through the area and is a tributary of the Clackamas River. Salmon and steelhead spawn in the Roaring River and the area is thick with Bears, cougars, mule deer, elk, spotted owls and pileated woodpeckers. Lupine or Indian paintbrush are common wildflowers in summer. Lakes in the area include the Rock Lakes and Serene Lake, while Cache Meadow is one of the many alpine meadows. The wilderness has five trails -- Shining Lake, Shellrock Lake, Serene Lake, Grouse Point and Dry Ridge. Prior to designation these trails were open to use by mountain bikes. Lakebed Geology Sensitivity N/A Lakebed Geology Composition andesite dacite diorite phylite (82%), amphibolite hornfels paragneiss undifferentiated metamorphic roc (18%), GC 1+2 (82%), GC 1+2+3 (82%), GC 4+5+6 (18%) Visitor Use Not reported in the database. -

Water Resources of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, Oregon

;-. -;_ i:· :.: · r!ID!.l~~rP ~cs~wtP~C§~ ;~:~ ·;·.; ':/ : ·,~[p#l '. ~rYtbJ!~ .: U®~lktrv ·· ~~~~~li~~D ··.··~.·- ~~;~ . ·:·l ·-: u.s. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY : .• .. · Wt1t~i R~6u"r;desJaveshgatioAs 76~'26. :-. _: ,. ) ·- :::, . ... _.. ,. ) ·. ,· ,_., ~- . · Pre:Paie~ i~ ¢o9pe,ratl6n ' "'rtth\i~l.e . · .. .·.·.·. .. .. .· ..· . :i CO~fEQBRATp.Q'TRt~~S , O FTB.EW~~M SPRifiG.$1{-ES.E~VAJI .p,N ·; .· _; i ·,.· :·_ \ WATER RESOURCES OF THE WARM SPRINGS INDIAN RESERVATION, OREGON By J. H. Robison and Antonius Laenen U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water Resources Investigations 7 6-26 Prepared in cooperation with the CONFEDERATED TRIBES OF THE WARM SPRINGS RESERVATION 1976 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Thomas S. Kleppe, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Vincent E. McKelvey, Director For additional information write to: U.S. Geological Survey P.O. Box 3202 Portland, Oregon 97208 ii CONTENTS Page Abstract----------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Geography---------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Geology------------------------------------------------------------------ 4 Clarno Formation---------------------------------------------------- 4 John Day Formation-------------------------------------------------- 4 Columbia River Basalt Group----------------------------------------- 5 Dalles Formation---------------------------------------------------- 5 Basalt-------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Andesite------------------------------------------------------------ -

Free Index (PDF)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Burns Paiute Tribal Reservation G-6 Siletz Reservation B-4 Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Reservation B-3 Umatilla Indian Reservation G-2 Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation H-9,10 Warm Springs Indian Reservation D-3,4 Ankeny National Wildlife Refuge B-4 Basket Slough National Wildlife Refuge B-4 Badger Creek Wilderness D-3 Bear Valley National Wildlife Refuge D-9 9 Middle Santiam Wilderness C-4 Mill Creek Wilderness E-4,5 Black Canyon Wilderness F-5 Monument Rock Wilderness G-5 Boulder Creek Wilderness C-7 Mount Hood National Forest C-4 to D-2 Bridge Creek Wilderness E-5 Mount Hood Wilderness D-3 Bull of the Woods Wilderness C,D-4 Mount Jefferson Wilderness D-4,5 Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument C-9,10 Mount Thielsen Wilderness C,D-7 Clackamas Wilderness C-3 to D-4 Mount Washington Wilderness D-5 Cold Springs National Wildlife Refuge F-2 Mountain Lakes Wilderness C-9 Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Newberry National Volcanic Monument D-6 C-2 to E-2 North Fork John Day Wilderness G-3,4 Columbia White Tailed Deer National Wildlife North Fork Umatilla Wilderness G-2 Refuge B-1 Ochoco National Forest E-4 to F-6 Copper Salmon Wilderness A-8 Olallie Scenic Area D-4 Crater Lake National Park C-7,8 Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area C-4 Crooked River National Grassland D-4 to E-5 Opal Creek Wilderness C-4 Cummins Creek Wilderness A,B-5 Oregon Badlands Wilderness D-5 to E-6 Deschutes National Forest C-7 to D-4 Oregon Cascades Recreation Area C,D-7 Diamond Craters Natural Area F-7 to G-8 Oregon Caves National Monument -

Warm Springs Research Project

OREGON STATE COLLEGE Warm Springs ResearchProject Final Report VOLUME IV: WATER RESOURCES Part 1.Report andRecommendati Decent OREGON STATE COLLEGE WAR,1 SPRINtS RESEARCH PILOJECT VOLUUE IV: WATER RESOURCES by Elmon E. Yoder, B0S. Department of Civil Engineering Part 1: Report and Recommendations This volume is part of the final report ofa study made by Oregon State College for the Confederated Tribes of the Warm SpringsReservation of Oregon. The remainder of the report is contained in the following: Volume I: Introduction and Survey of HumanResources; Volume II: Education; Volume III: TheAgricultural Economy; Volume IV: Water Resources, Part 2: Appendices andBibliography; Volume V: Physical Resources. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I IITRODUCTION Chapter Section 1-1: Synopsis Page 1-1 1 Contents of Report 1 1-1.2 Ground Water 1-1.3 Surface Water 1-1.4 Duty of Water 2 Section 1-2: Objectives 1-2.1 Purpose 2 1-2.2 Immediate Objective 2 1-2.3 Long Range Objective 2 Section 1-3: Organization of Report 1-3.1 Report Content 1-3.2 Chapter Content Section 1-4: Method of Investigation 1-4.1 Source of Data 4 1-4.5 Adequacy of Data 5 1-4.6 Extension of Data 5 CHAPTER II HYDROLOGY OF GROUND WATER Section 2-1: History of Investigations 2-1.1 Existing Ground Water Data 2-1.3 Work of the U. S. Geological Survey Section 2-2: Classification of Sub-Surface Water 2-2.1 Interstitial and Internal Water 6 2-2.2 External Interstitial Water 1 2-2.3 Zone of Aeration 7 2-2.4 Perched Water 7 2-2.5 Zone of Saturation 7 2-2,6 Classification by Texture and Structure of