Sustainable Seafood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Digital Visitors Guide

2019 | 2020 Official Visitors Guide SurfCityUSA.com HUNTINGTON BEACH PROFILES IN INSPIRATION 10 5 AMAZING #SURFCITYWOMEN SURPRISING THINGS! MY BEST DAY EVER 7 LOCALS REVEAL THEIR TOWN’S SECRETS #SurfCityUSA ocean inspired coastal places + open spaces Your blissful escape awaits at The Waterfront Beach Resort. Enjoy striking views of the sunset at our exclusive Offshore 9 Rooftop Lounge, while you savor a delicious craft cocktail or lite bite. Then, cast your worries out to sea as you indulge in a relaxing massage at our all-new coastal oasis, Drift a Waterfront Spa. It’s the perfect space to unwind and it’s only at The Waterfront. 21100 Pacific Coast Highway • Huntington Beach, CA 92648 • 714.845.8000 • waterfrontresort.com ocean inspired coastal places + open spaces Your blissful escape awaits at The Waterfront Beach Resort. Enjoy striking views of the sunset at our exclusive Offshore 9 Rooftop Lounge, while you savor a delicious craft cocktail or lite bite. Then, cast your worries out to sea as you indulge in a relaxing massage at our all-new coastal oasis, Drift a Waterfront Spa. It’s the perfect space to unwind and it’s only at The Waterfront. 21100 Pacific Coast Highway • Huntington Beach, CA 92648 • 714.845.8000 • waterfrontresort.com It’s good not to be home #hyatthb Join us on the patio for ocean views or in the bar for artisinal cocktails, craft beer, world class wines and signature appetizer bar jars. watertablehb.com 714 845 4776 Relax your mind, body and soul. Our spa blends a Mediterranean feel with inspirations from the Pacifi c. -

Page 1 of 239 05-Jun-2019 7:38:44 State of California Dept. of Alcoholic

05-Jun-2019 State of California Page 1 of 239 7:38:44 Dept. of Alcoholic Beverage Control List of All Surrendered Retail Licenses in MONROVIA District File M Dup Current Type GEO Primary Name DBA Name Type Number I Count Status Status Date Dist Prem Street Address ------ ------------ - -------- ------------- ----------------- -------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------ 20 250606 Y SUREND 02/25/2017 1900 KOJONROJ, PONGPUN DBA: MINI A 1 MART 2 11550 COLIMA RD WHITTIER, CA 90604 61 274544 Y SUREND 04/17/2017 1900 JUAREZ MUNOZ, BARTOLO DBA: CAL TIKI BAR 2 3835 WHITTIER BLVD LOS ANGELES, CA 90023-2430 20 389309 Y SUREND 12/13/2017 1900 BOULOS, LEON MORID DBA: EDDIES MINI MART 2 11236 WHITTIER BLVD WHITTIER, CA 90606 48 427779 Y SUREND 12/04/2015 1900 OCEANS SPORTS BAR INC DBA: OCEANS SPORTS BAR 2 14304-08 TELEGRAPH RD ATTN FREDERICK ALANIS WHITTIER, CA 90604-2905 41 507614 Y SUREND 02/04/2019 1900 GUANGYANG INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT INC DBA: LITTLE SHEEP MONGOLIAN HOT POT 2 1655 S AZUSA AVE STE E HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745-3829 21 512694 Y SUREND 04/02/2014 1900 HONG KONG SUPERMARKET OF HACIENDA HEIGHTS,DBA: L HONGTD KONG SUPERMARKET 2 3130 COLIMA RD HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745-6301 41 520103 Y SUREND 07/24/2018 1900 MAMMA'S BRICK OVEN, INC. DBA: MAMMAS BRICK OVEN PIZZA & PASTA 2 311 S ROSEMEAD BLVD #102-373 PASADENA, CA 91107-4954 47 568538 Y SUREND 09/27/2018 1900 HUASHI GARDEN DBA: HUASHI GARDEN 2 19240 COLIMA RD ROWLAND HEIGHTS, CA 91748-3004 41 571291 Y SUREND 12/08/2018 1900 JANG'S FAMILY CORPORATION DBA: MISONG 2 18438 COLIMA RD STE 107 ROWLAND HEIGHTS, CA 91748-5822 41 571886 Y SUREND 07/16/2018 1900 BOO FACTOR LLC DBA: AMY'S PATIO CAFE 2 900 E ALTADENA DR ALTADENA, CA 91001-2034 21 407121 Y SUREND 06/08/2015 1901 RALPHS GROCERY COMPANY DBA: RALPHS 199 2 345 E MAIN ST ALHAMBRA, CA 91801 05-Jun-2019 State of California Page 2 of 239 7:38:44 Dept. -

SLIM CHICKENS FALL 2021 on the COVER When Chicken Wings Are in Short Supply, FALL 2021 Boneless Alternatives Can Stand In

MENU MUST-HAVES MONEY MOVES MEETING THE MOMENT FOOD FANATICS TAKE THAT Limited Time Only 2.O EARTH MATTERS Umami is the punch menus welcome, Make bank with smarter LTO, Restaurateurs on climate change, page 12 page 51 page 65 SLIM CHICKENS SLIM FALL 2021 FALL CHICKENS WING STAND-INS STEP UP ON THE COVER When chicken wings are in short supply, FALL 2021 boneless alternatives can stand in. Add some thrill Sharing the Love of Food—Inspiring Business Success See page 30. MENU MUST-HAVES MONEY MOVES to your bar & grill. PILE IT ON THE SMARTER WAY TO LTO From sports bars to chef-driven concepts, Make bank with aggressive limited- over-the-top dishes score. time- only options. 5 51 ™ ® SIDEWINDERS Fries Junior Cut Featuring Conquest Brand Batter TAKE THAT THE POWER OF TWO Umami is the punch that diners welcome. Get an edge by pairing up with a brand. 12 54 KNEAD-TO-KNOW PIZZA FLEX YOUR MENU MUSCLE Light clear coat batter Innovation in dough and toppings rise Strategic pricing can benefit the lets the potato flavor when there’s time on your hands. bottom line. shine through 22 58 CHANGE IT UP ON THE FLY 5 ways to step up your SEO. How boneless wings can take off when 61 Unique shape for wings are grounded. Instagram-worthy 30 presentations MEETING THE PLENTY TO BEER MOMENT Complex flavors demand suds that can stand up and complement. EARTH MATTERS 40 Restaurateurs respond to the menu’s role in climate change. TREND TRACKER 65 Thicker cut and clear Homing in on what’s coming and going. -

SBA Franchise Directory Effective March 31, 2020

SBA Franchise Directory Effective March 31, 2020 SBA SBA FRANCHISE FRANCHISE IS AN SBA IDENTIFIER IDENTIFIER MEETS FTC ADDENDUM SBA ADDENDUM ‐ NEGOTIATED CODE Start CODE BRAND DEFINITION? NEEDED? Form 2462 ADDENDUM Date NOTES When the real estate where the franchise business is located will secure the SBA‐guaranteed loan, the Collateral Assignment of Lease and Lease S3606 #The Cheat Meal Headquarters by Brothers Bruno Pizza Y Y Y N 10/23/2018 Addendum may not be executed. S2860 (ART) Art Recovery Technologies Y Y Y N 04/04/2018 S0001 1‐800 Dryclean Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S2022 1‐800 Packouts Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0002 1‐800 Water Damage Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0003 1‐800‐DRYCARPET Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0004 1‐800‐Flowers.com Y Y Y 10/01/2017 S0005 1‐800‐GOT‐JUNK? Y Y Y 10/01/2017 Lender/CDC must ensure they secure the appropriate lien position on all S3493 1‐800‐JUNKPRO Y Y Y N 09/10/2018 collateral in accordance with SOP 50 10. S0006 1‐800‐PACK‐RAT Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S3651 1‐800‐PLUMBER Y Y Y N 11/06/2018 S0007 1‐800‐Radiator & A/C Y Y Y 10/01/2017 1.800.Vending Purchase Agreement N N 06/11/2019 S0008 10/MINUTE MANICURE/10 MINUTE MANICURE Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 1. When the real estate where the franchise business is located will secure the SBA‐guaranteed loan, the Addendum to Lease may not be executed. -

Restaurantactivityreport.Com - Restaurant Lead Report Current Real Estate Transactions, Leases Signed, Ownership Changes, and Business Brokerage Activity

RestaurantActivityReport.com - Restaurant Lead Report Current Real Estate Transactions, Leases Signed, Ownership Changes, and Business Brokerage Activity. Nonna's Pizza & Pasta Steve Champagne Independent 104 Harding Street Owners [email protected] 508-797-1011 Publication Date: 3/2/2017 Worcester MA 01604 2017 July www.nichehospitality.com Nonna's Pizza & Pasta will be opening in the summer of 2017. The casual restaurant will serve $20 and under Long Island-style pizza, as well as pastas and other Italian dishes. The will have room for 120 Pizza/Italian patrons and will have a full bar. Nonna's Pizza & Pasta will be located at 104 Harding Street, Worcester, Massachusetts, 01604. The current contact is for the Niche Hospitality Group at their Bocado Tapas restaurant at 508-797-1011 or email them at [email protected] Railers Tavern Steve Champagne Independent 105 Commercial Street Owners [email protected] Worcester Railers 508-797-1011 Publication Date: 3/2/2017 Worcester MA 01608 2017 October www.nichehospitality.com Railers Tavern will open in October 2017. The casual restaurant will be a meeting place for fans $20 and under watching the Worcester Railers hockey team. They will serve traditional bar and grill fare and Bar & Grill/ Pub also offer a full bar. Railers Tavern will be located at 105 Commercial Street, Worcester, Massachusetts, 01608. The current contact is for Niche Hospitality through their Bocado Tapas restaurant at 508-797-1011 or email them at [email protected] Friendly's Lynne Geiger Franchise 710 Milford Road POS Systems Administrator 413-543-2400 Publication Date: 3/2/2017 Merrimack NH 03054 2017 March www.friendlys.com Friendly's will open by March of 2017 at 710 Milford Road in Merrimack, New Hampshire $20 and under 03054. -

Page 1 of 240 17-Sep-2019 10:27:53 State of California Dept. of Alcoholic

17-Sep-2019 State of California Page 1 of 240 10:27:53 Dept. of Alcoholic Beverage Control List of All Surrendered Retail Licenses in MONROVIA District File M Dup Current Type GEO Primary Name DBA Name Type Number I Count Status Status Date Dist Prem Street Address ------ ------------ - -------- ------------- ----------------- -------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------ 20 250606 Y SUREND 02/25/2017 1900 KOJONROJ, PONGPUN DBA: MINI A 1 MART 2 11550 COLIMA RD WHITTIER, CA 90604 20 389309 Y SUREND 12/13/2017 1900 BOULOS, LEON MORID DBA: EDDIES MINI MART 2 11236 WHITTIER BLVD WHITTIER, CA 90606-1436 48 427779 Y SUREND 12/04/2015 1900 OCEANS SPORTS BAR INC DBA: OCEANS SPORTS BAR 2 14304-08 TELEGRAPH RD ATTN FREDERICK ALANIS WHITTIER, CA 90604-2905 20 487268 Y SUREND 08/30/2019 1900 PATEL, NIRANJANA PANKAJ DBA: CANYON VIEW ALTA DENA DAIRY 2 756 E FOOTHILL BLVD SAN DIMAS, CA 91773-1209 41 507614 Y SUREND 02/04/2019 1900 GUANGYANG INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT INC DBA: LITTLE SHEEP MONGOLIAN HOT POT 2 1655 S AZUSA AVE STE E HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745-3829 21 512694 Y SUREND 04/02/2014 1900 HONG KONG SUPERMARKET OF HACIENDA HEIGHTS,DBA: L HONGTD KONG SUPERMARKET 2 3130 COLIMA RD HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745-6301 47 568538 Y SUREND 09/27/2018 1900 HUASHI GARDEN DBA: HUASHI GARDEN 2 19240 COLIMA RD ROWLAND HEIGHTS, CA 91748-3004 41 571291 Y SUREND 12/08/2018 1900 JANG'S FAMILY CORPORATION DBA: MISONG 2 18438 COLIMA RD STE 107 ROWLAND HEIGHTS, CA 91748-5822 40 603208 Y SUREND 09/09/2019 1900 VITAL, MIGUEL ANGEL DBA: TORITO BAR 2 5720-20-1/2 E BEVERLY BLVD LOS ANGELES, CA 90022 47 583682 N 1 SUREND 10/30/2017 1901 LOS AMIGOS SBG, LLC DBA: LOS AMIGOS MEXICAN GRILL AND CANTINA 2 118 W MAIN ST ALHAMBRA, CA 91801-3511 47 583682 Y SUREND 08/13/2019 1901 LOS AMIGOS SBG, LLC DBA: LOS AMIGOS MEXICAN GRILL AND CANTINA 2 118 W MAIN ST ALHAMBRA, CA 91801-3511 17-Sep-2019 State of California Page 2 of 240 10:27:53 Dept. -

SBA ADDENDUM ‐ Form 2462

SBA SBA FRANCHISE FRANCHISE IS AN SBA IDENTIFIER IDENTIFIER MEETS FTC ADDENDUM SBA ADDENDUM ‐ NEGOTIATED CODE Start CODE BRAND DEFINITION? NEEDED? Form 2462 ADDENDUM Date NOTES When the real estate where the franchise business is located will secure the SBA‐guaranteed loan, the Collateral Assignment of Lease and Lease S3606 #The Cheat Meat Headquarters by Brother Bruno's Pizza Y Y Y N 10/23/2018 Addendum may not be executed. S2860 (ART) Art Recovery Technologies Y Y Y N 04/04/2018 S0001 1‐800 Dryclean Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S2022 1‐800 Packouts Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0002 1‐800 Water Damage Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0003 1‐800‐DRYCARPET Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S0004 1‐800‐Flowers.com Y Y Y 10/01/2017 S0005 1‐800‐GOT‐JUNK? Y Y Y 10/01/2017 Lender/CDC must ensure they secure the appropriate lien position on all S3493 1‐800‐JUNKPRO Y Y Y N 09/10/2018 collateral in accordance with SOP 50 10. S0006 1‐800‐PACK‐RAT Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 S3651 1‐800‐PLUMBER Y Y Y N 11/06/2018 S0007 1‐800‐Radiator & A/C Y Y Y 10/01/2017 S0008 10/MINUTE MANICURE/10 MINUTE MANICURE Y Y Y N 10/01/2017 1. When the real estate where the franchise business is located will secure the SBA‐guaranteed loan, the Addendum to Lease may not be executed. 2. Lender/CDC must ensure they secure the appropriate lien position on all collateral in accordance with the SOP 50 10. -

Innovative Restaurant Brands and Executives Shaping the Fast Casual Segment Oracle Hospitality

Innovative restaurant brands and executives shaping the fast casual segment Oracle Hospitality One Integrated Cloud for Food & Beverage • Point of Sale • Loss Prevention • Labor • Kiosks • Loyalty • Inventory • Mobile • Reporting oracle.com/goto/fast-casual or call 1.866.287.4736 Copyright © 2018, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Oracle and Java are registered trademarks of Oracle and/or its affiliates. PUB NOTE: Please use center marks to align page. Resize Job #: R_418M_IND00170_FastCasualFB_HSP_8.5x11 PRODUCTION NOTES RELEASED Ref #: M_418M_IND00168_FastCasualFB_HSP_8x10.5 READER LASER% Headline: Oracle Hospitality Black Keyline 4/06 Live: N/A Trim: 8.5” x 11” 01 2018 Bleed: N/A Prints! 8.5” x 11” Please examine these publication materials carefully. Fonts: Univers LT Std. 75 Black, 65 Bold, 55 Roman, 45 Light, Any questions regarding the materials, please 67 Bold Condensed, 57 Condensed contact Darci Terlizzi (650) 506-9775 2018 Executive Summary The Fast Casual Top 100 Movers & Shakers – for the past 14 years -- has recognized the industry’s most innovative brands. As always, making the list is a testament to a company’s growth and sales accomplishments but also honors innovation in the use of technology to enhance the customer experience and a willingness to take risks in the name of brand elevation. Tom Harper Although this year’s class features a variety of concepts, from CEO those specializing in pizza and burgers to Mexican food and [email protected] Cherryh Cansler chicken, “healthful” was the standout theme of 2018. In fact, 20 Editorial director, Networld Media Group Kathy Doyle of the 75 brands fit that category, which was by far the most out President & publisher of any year. -

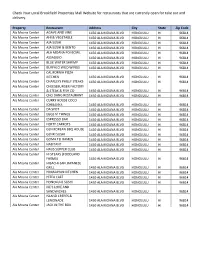

Check Your Local Brookfield Properties Mall Website for Restaurants That Are Currently Open for Take out and Delivery

Check Your Local Brookfield Properties Mall Website for restaurants that are currently open for take out and delivery. Property Restaurant Address City State Zip Code Ala Moana Center AGAVE AND VINE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AHI & VEGETABLE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AJA SUSHI 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AJA SUSHI & BENTO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ALA MOANA POI BOWL 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ASSAGGIO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center BLUE WATER SHRIMP 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center BUFFALO WILD WINGS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CALIFORNIA PIZZA KITCHEN 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHARLEYS PHILLY STEAKS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHEESEBURGER FACTORY & STEAK & FISH CO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHO DANG RESTAURANT 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CURRY HOUSE COCO ICHIBANYA 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center DA SPOT 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center EGGS N' THINGS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ESPRESSO BAR 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center FORTY CARROTS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center GEN KOREAN BBQ HOUSE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center GENKI SUSHI 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana -

2021 Fast Casual Top 100 Movers & Shakers

Innovative restaurant brands and executives shaping the fast casual segment sponsored by OUR PLATFORM. YOUR FOUNDATION. You can’t take chances when choosing a POS platform. 300,000+ installations and 20 billion transactions is your assurance that Givex delivers, one interaction after another. If you’re focused on success, we’ll show you how to accelerate customer acquisition, retention and operational efficiency. • Integrated Payment Providers • Online, Delivery, Contactless • Multichannel Sales • CRM + Labour Management • Open API • Analytics and Reporting • Mobile and Kiosks • Gift and Loyalty • Kitchen Display System • Menu and Inventory Prove it to yourself. Book a one-hour, no-commitment demo now. Learn more at www.givex.com ExecutiveEXECUTIVE Summary REPORT Since its creation 16 years ago, the Fast Casual Top 100 Movers & Shakers list has recognized the industry’s most successful brands. And just like in our daily lives, people measure success in different ways. For some, it’s about having the most money or power. Others base it on how Tom Harper happy their relationships make them, CEO [email protected] while some feel compelled to strive for specific career or charitable goals. Kathy Doyle President & Publisher The Top 100 is similar in that it’s not [email protected] always looking for the most profitable or fastest-growing brands. Sure, those elements Cherryh Cansler are important and often come into play, but companies also make this list for their dedication to VP of Editorial [email protected] innovation, leadership and resilience. That last quality -- resilience -- has never been more important than in this past year as the sponsored by global pandemic forced companies to change everything from their operating models and menus to store layouts and labor plans, while still managing to take care of the people in their communities. -

Top 100 Fast Casual

Innovative restaurant brands and executives shaping the fast casual segment Oracle Food and Beverage One Integrated Cloud for: • Point of Sale • Reporting • Labor • Inventory • Loyalty • Kiosk • Mobile • Data Science oracle.com/food-beverage or call 1.866.287.4736 Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Oracle and Java are registered trademarks of Oracle and/or its affiliates. 2019 Executive Summary Wow Bao is this year’s Fast Casual Top 100 Mover & Shaker, and the fact that a concept focused on healthy cuisine topped the list is proof that customers are embracing more healthful food options. In fact, 17 of the Top 25 brands on this year’s list fall into the healthy category, which often includes Asian and Mediterranean concepts. In its 2018 Healthy Eating Consumer Trend Report, Technomic Tom Harper found that consumers were making food and beverage choices CEO based on their personal definition of health. The report found that [email protected] Cherryh Cansler 66% of consumers looked for calorie counts on restaurant menus Editorial director, Networld Media Group Kathy Doyle at least some of the time, and 34% said they’d be likely to order President & publisher [email protected] dishes made with vegetables. “The foodservice landscape will become more competitive when it comes to tastier, more Cherryh Cansler Editorial director innovative healthy menu offerings,” said Maia Chang, senior research analyst at Technomic. [email protected] “This means that more brands will face additional pressure to differentiate through transparency and preparation techniques, as well as brand and sourcing stories.” Brittany Warren Director of content marketing [email protected] Choosing the Top 100 Although nearly half the brands on this year’s list fell into the healthy category, a variety of cuisine types, including pizza, burgers, barbecue and Mexican cuisine, still found a place. -

Pivot! How the Restaurant Industry Adapted During COVID-19 Restrictions

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2516-8142.htm Restaurant Pivot! How the restaurant industry industry adapted during during COVID-19 restrictions COVID-19 Cortney L. Norris, Scott Taylor Jr and D. Christopher Taylor Conrad Hilton College of Hotel and Restaurant Management, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA Received 14 September 2020 Revised 25 January 2021 Accepted 26 January 2021 Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this systematic review is to highlight some of the business model changes restaurants, bars and beverage producers undertook to modify their operations in order to not only stay in business but also to better serve their employees and communities during the COVID-19 crisis. Design/methodology/approach – An analysis was conducted on 200 industry articles and categorized into three major themes: expansion of take-out/delivery, innovative practices, and community outreach/corporate support, each are further subdivided into additional themes. The systematic review is further supported by personal interviews with industry professionals. Findings – This research finds that there were many different approaches used in adjusting business models in response to the dining restrictions put in place due to COVID-19. From these approaches, themes were developed whichresultedinuncoveringsomesuggestionssuchasdeveloping contingency plans, being flexible and creative, eliminating menu items, investing in a communication platform and getting involved with local government. In addition, some practices operators should be mindful of such as selling gift cards and starting a crowdfund. Research limitations/implications – This research provides a systematic analysis of business model changes that occurred due to COVID-19 dining restrictions.