1 Surgical Pathology of the Mouth and Jaws R. A. Cawson, J. D. Langdon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basal Cell Adenoma of Zygomatic Salivary Gland in a Young Dog – First Case Report in Mozambique

RPCV (2015) 110 (595-596) 229-232 Basal cell adenoma of zygomatic salivary gland in a young dog – First case report in Mozambique Adenoma das células basais da glândula salivar zigomática em cão jovem – Primeiro relato de caso em Moçambique Ivan F. Charas dos Santos*1,2, José M.M. Cardoso1, Giovanna C. Brombini3 Bruna Brancalion3 1Departamento de Cirurgia, Faculdade de Veterinária, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Moçambique 2Pós-doutorando (Bolsista FAPESP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anestesiologia Veterinária, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia (FMVZ), Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Botucatu, São Paulo, Brasil. 3Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia (FMVZ), Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP),Botucatu, São Paulo, Brasil. Summary: Basal cell adenoma of zygomatic salivary gland Introduction was described in a 1.2 years old Rottweiler dog with swelling of right zygomatic region tissue. Clinical signs were related to Salivary glands diseases in small animals include anorexia, slight pain on either opening of the mouth. Complete blood count, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, thoracic radio- mucocele, salivary gland fistula, sialadenitis, sialad- graphic examination; and transabdominal ultrasound showed enosis, sialolithiasis and less neoplasia (Spangler and no alteration. The findings of cytology examination were con- Culbertson, 1991; Johnson, 2008). Primary tumours sistent with benign tumour and surgical treatment was elected. of salivary glands are rare in dogs and not common- The histopathologic examinations were consistent with basal ly reported in small animals. The incidence is about cell adenoma of zygomatic salivary gland. Seven days after the surgery no alteration was observed. One year later, the dog re- 0.17% in dogs with age between 10 and 12 years turned to check up and confirmed that the dog was healthy and old (Spangler and Culbertson, 1991; Hammer et al., free of clinical and laboratorial signs of tumour recurrence or 2001; Head and Else, 2002). -

Diseases of Salivary Glands: Review

ISSN: 1812–1217 Diseases of Salivary Glands: Review Alhan D Al-Moula Department of Dental Basic Science BDS, MSc (Assist Lect) College of Dentistry, University of Mosul اخلﻻضة امخجوًف امفموي تُئة رطبة، حتخوي ػىل طبلة ركِلة من امسائل ثدغى انوؼاب ثغطي امسطوح ادلاخوَة و متﻷ امفراغات تني ااطَة امفموًة و اﻷس نان. انوؼاب سائل مؼلد، ًنذج من امغدد انوؼاتَة، اذلي ًوؼة دورا" ىاما" يف اﶈافظة ػىل سﻻمة امفم. املرىض اذلٍن ؼًاهون من هلص يف اﻷفراز انوؼايب حكون دلهيم مشبلك يف اﻷلك، امخحدث، و امبوع و ًطبحون غرضة مﻷههتاابت يف اﻷغش َة ااطَة و امنخر املندرش يف اﻷس نان. ًوخد ثﻻثة أزواج من امغدد انوؼاتَة ام ئرُسة – امغدة امنكفِة، امغدة حتت امفكِة، و حتت انوساهَة، موضؼيا ٍكون خارج امخجوًف امفموي، يف حمفظة و ميخد هظاهما املنَوي مَفرغ افرازاهتا. وًوخد أًضا" امؼدًد من امغدد انوؼاتَة امطغرية ، انوساهَة، اتحنكِة، ادلىوزيًة، انوساهَة احلنكِة وما كبل امرخوًة، ٍكون موضؼيا مﻷسفل و مضن امغشاء ااطي، غري حماطة مبحفظة مع هجاز كنَوي كطري. افرازات امغدد انوؼاتَة ام ئرُسة مُست مدشاهبة. امغدة امفكِة ثفرز مؼاب مطيل غين ابﻷمِﻻز، وامغدة حتت امفكِة ثنذج مؼاب غين اباط، أما امغدة حتت انوساهَة ثنذج مؼااب" مزخا". ثبؼا" ميذه اﻷخذﻻفات، انوؼاب املوحود يق امفم ٌشار امَو مكزجي. ح كرَة املزجي انوؼايب مُس ثس َطا" واملادة اﻷضافِة اموػة من لك املفرزات انوؼاتَة، اكمؼدًد من امربوثُنات ثنذلل ثرسػة وثوخطق هبدروكس َل اﻷتُذاًت مﻷس نان و سطوح ااطَة امفموًة. ثبدأ أمراض امغدد انوؼاتَة ػادة تخغريات اندرة يف املفرزات و ام كرتَة، وىذه امخغريات ثؤثر اثهواي" من خﻻل جشلك انووحية اجلرثومِة و املوح، اميت تدورىا ثؤدي اىل خنور مذفش َة وأمراض وس َج دامعة. ىذه اﻷمراض ميكن أن ثطبح شدًدة تؼد املؼاجلة امشؼاغَة ﻷن امؼدًد من احلاﻻت اجليازًة )مثل امسكري، امخوَف اهكُيس( ثؤثر يف اجلراين انوؼايب، و ٌش خيك املرض من حفاف يف امفم. -

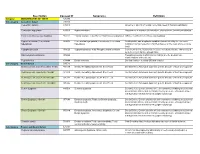

ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes Effective 10/1/2011 (V29.0) Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes effective 10/1/2011 (v29.0) Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 0010 Cholera d/t vib cholerae 00801 Int inf e coli entrpath 01086 Prim prg TB NEC-oth test 0011 Cholera d/t vib el tor 00802 Int inf e coli entrtoxgn 01090 Primary TB NOS-unspec 0019 Cholera NOS 00803 Int inf e coli entrnvsv 01091 Primary TB NOS-no exam 0020 Typhoid fever 00804 Int inf e coli entrhmrg 01092 Primary TB NOS-exam unkn 0021 Paratyphoid fever a 00809 Int inf e coli spcf NEC 01093 Primary TB NOS-micro dx 0022 Paratyphoid fever b 0081 Arizona enteritis 01094 Primary TB NOS-cult dx 0023 Paratyphoid fever c 0082 Aerobacter enteritis 01095 Primary TB NOS-histo dx 0029 Paratyphoid fever NOS 0083 Proteus enteritis 01096 Primary TB NOS-oth test 0030 Salmonella enteritis 00841 Staphylococc enteritis 01100 TB lung infiltr-unspec 0031 Salmonella septicemia 00842 Pseudomonas enteritis 01101 TB lung infiltr-no exam 00320 Local salmonella inf NOS 00843 Int infec campylobacter 01102 TB lung infiltr-exm unkn 00321 Salmonella meningitis 00844 Int inf yrsnia entrcltca 01103 TB lung infiltr-micro dx 00322 Salmonella pneumonia 00845 Int inf clstrdium dfcile 01104 TB lung infiltr-cult dx 00323 Salmonella arthritis 00846 Intes infec oth anerobes 01105 TB lung infiltr-histo dx 00324 Salmonella osteomyelitis 00847 Int inf oth grm neg bctr 01106 TB lung infiltr-oth test 00329 Local salmonella inf NEC 00849 Bacterial enteritis NEC 01110 TB lung nodular-unspec 0038 Salmonella infection NEC 0085 Bacterial enteritis NOS 01111 TB lung nodular-no exam 0039 -

Statistical Analysis Plan

Cover Page for Statistical Analysis Plan Sponsor name: Novo Nordisk A/S NCT number NCT03061214 Sponsor trial ID: NN9535-4114 Official title of study: SUSTAINTM CHINA - Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Document date: 22 August 2019 Semaglutide s.c (Ozempic®) Date: 22 August 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL Clinical Trial Report Status: Final Appendix 16.1.9 16.1.9 Documentation of statistical methods List of contents Statistical analysis plan...................................................................................................................... /LQN Statistical documentation................................................................................................................... /LQN Redacted VWDWLVWLFDODQDO\VLVSODQ Includes redaction of personal identifiable information only. Statistical Analysis Plan Date: 28 May 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL UTN:U1111-1149-0432 Status: Final EudraCT No.:NA Page: 1 of 30 Statistical Analysis Plan Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Author Biostatistics Semaglutide s.c. This confidential document is the property of Novo Nordisk. No unpublished information contained herein may be disclosed without prior written approval from Novo Nordisk. Access to this document must be restricted to relevant parties.This -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

20 Diagnosis and Management of Salivary Gland Disorders

Diagnosis and Management of Salivary Gland Disorders Michael Miloro and Sterling R. Schow CHAPTER CHAPTER OUTLINE EMBRYOLOGY, ANATOMY, AND PHYSIOLOGY OBSTRUCTIVE SALIVARY GLAND DISEASE DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES Sialolithiasis History and Clinical Examination Salivary Gland MUCOUS RETENTION AND EXTRAVASATION Radiology Plain Film Radiographs Sialography PHENOMENA Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Mucocele Imaging, and Ultrasound Ranula Salivary Scintigraphy (Radioactive Isotope SALIVARY GLAND INFECTIONS Scanning) NECROTIZING SIALOMETAPLASIA SJOGREN'S SYNDROME Salivary Gland Endoscopy (Sialoendoscopy) TRAUMATIC SALIVARY GLAND INJURIES Sialochernistry NEOPLASTIC SALIVARY GLAND DISORDERS Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Benign Salivary Gland Tumors Salivary Gland Biopsy Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors he clinician is frequently confronted with EMBRYOLOGY, ANATOMY, AND PHYSIOLOG the necessity of assessing and The salivary glands can be divided into two groups: managing salivary gland disorders. A the minor and major glands. All salivary glands develop thorough knowledge of the embryology, anatomy, and from the embryonic oral cavity as buds of pathophysiology is necessary to treat patients epithelium that extend into the underlying appropriately. This chapter examines the cause, mesenchymal tissues. The epithelial ingrowths diagnostic methodology, radiographic evaluation, and branch to form a primitive ductal system that management of a variety of salivary gland disorders, eventually becomes canalized to provide for drainage including sialolithiasis and obstructive phenomena of salivary secretions. The minor salivary glands begin (e.g., mucocele and ranula), acute and chronic to develop around the fortieth day in utero, where- as salivary gland infections, traumatic salivary gland the larger major glands begin to develop slightly earli- disorders, S]6gren's syndrome (SS), necrotizing er, at about the thirty-fifth day in utero. At around sialometaplasia, and benign and malignant salivary the seventh or eighth month in utero, secretory cells gland tumors. -

The Effect of Botulinum Toxin on an Iatrogenic Sialo-Cutaneous Fistula

Arch Craniofac Surg Vol.17 No.4, 237-239 Archives of Cr aniofacial Surgery https://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2016.17.4.237 The Effect of Botulinum Toxin on an Iatrogenic Sialo-Cutaneous Fistula Seung Eun Hong, A sialo-cutaneous fistula is a communication between the skin and a salivary gland or duct Jung Woo Kwon, discharging saliva. Trauma and iatrogenic complications are the most common causes So Ra Kang, of this condition. Treatments include aspiration, compression, and the administration of Bo Young Park systemic anticholinergics; however, their effects are transient and unsatisfactory in most cases. We had a case of a patient who developed an iatrogenic sialo-cutaneous fistula Department of Plastic and Reconstructive after wide excision of squamous cell carcinoma in the parotid region that was not treated Surgery, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Case Report Hospital, Ewha Womans University School of with conventional management, but instead completely resolved with the injection of Medicine, Seoul, Korea botulinum toxin. Based on our experience, we recommend the injection of botulinum toxin into the salivary glands, especially the parotid gland, as a conservative treatment option for sialo-cutaneous fistula. No potential conflict of interest relevant to Keywords: Salivary gland fistula / Botulinum toxins / Squamous cell carcinoma this article was reported. INTRODUCTION vasive, stressful, and lengthy than conventional methods. We re- port a case in which an iatrogenic sialo-cutaneous fistula in the A sialo-cutaneous fistula is defined as a communication between preauricular area after skin cancer removal was successfully treat- the skin and a salivary gland resulting in the discharge of saliva ed with the injection of type A botulinum toxin. -

Non-Dental Oral Cavity Findings in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 9 Non-dental oral cavity findings in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis Madalina-Gabriela Indre PROF. DR. OCTAVIAN FODOR REGIONAL INSTITUTE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY, CLUJ- NAPOCA, ROMANIA Darius Sampelean IULIU HAȚIEGANU UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY, 4TH MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, CLUJ- NAPOCA, ROMANIA Vlad Taru IULIU HAȚIEGANU UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY, 4TH MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, CLUJ- NAPOCA, ROMANIA, [email protected] Angela Cozma IULIU HAȚIEGANU UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY, 4TH MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, CLUJ- NAPOCA, ROMANIA Dorel Sampelean IULIU HAȚIEGANU UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY, 4TH MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, CLUJ- NFollowAPOCA, this ROM andANI additionalA works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms Part of the Digestive, Oral, and Skin Physiology Commons, Gastroenterology Commons, Other Medical SeeSpecialties next page Commons for additional, and the authors Otolar yngology Commons Recommended Citation Indre, Madalina-Gabriela; Sampelean, Darius; Taru, Vlad; Cozma, Angela; Sampelean, Dorel; Milaciu, Mircea Vasile; and Orasan, Olga Hilda () "Non-dental oral cavity findings in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis," Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. DOI: 10.22543/7674.81.P6070 Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol8/iss1/9 This Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal -

SNODENT (Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry)

ANSI/ADA Standard No. 2000.2 Approved by ANSI: December 3, 2018 American National Standard/ American Dental Association Standard No. 2000.2 (2018 Revision) SNODENT (Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry) 2018 Copyright © 2018 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Any form of reproduction is strictly prohibited without prior written permission. ADA Standard No. 2000.2 - 2018 AMERICAN NATIONAL STANDARD/AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION STANDARD NO. 2000.2 FOR SNODENT (SYSTEMIZED NOMENCLATURE OF DENTISTRY) FOREWORD (This Foreword does not form a part of ANSI/ADA Standard No. 2000.2 for SNODENT (Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry). The ADA SNODENT Canvass Committee has approved ANSI/ADA Standard No. 2000.2 for SNODENT (Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry). The Committee has representation from all interests in the United States in the development of a standardized clinical terminology for dentistry. The Committee has adopted the standard, showing professional recognition of its usefulness in dentistry, and has forwarded it to the American National Standards Institute with a recommendation that it be approved as an American National Standard. The American National Standards Institute granted approval of ADA Standard No. 2000.2 as an American National Standard on December 3, 2018. A standard electronic health record (EHR) and interoperable national health information infrastructure require the use of uniform health information standards, including a common clinical language. Data must be collected and maintained in a standardized format, using uniform definitions, in order to link data within an EHR system or share health information among systems. The lack of standards has been a key barrier to electronic connectivity in healthcare. Together, standard clinical terminologies and classifications represent a common medical language, allowing clinical data to be effectively utilized and shared among EHR systems. -

Salivary Gland: Oncologic Imaging

Salivary Gland: Oncologic Imaging Uday Y. Mandalia, MBBS, BSc, MRCPCH, FRCRa,*, Francois N. Porte, MBBS, FRCRa, David C. Howlett, FRCP, FRCRb KEYWORDS Salivary gland Neoplasm Ultrasound Ultrasound-guided biopsy KEY POINTS Salivary gland neoplasms constitute a wide range of benign and malignant disorders and imaging constitutes an integral part of the initial assessment of a suspected salivary gland lesion. Because of their location, the salivary glands are readily accessible with high-resolution ultrasound, which is considered the first-line imaging modality in many centers. By providing information regarding the site, nature, and extent of disorder, ultrasound can charac- terize a lesion with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity. Ultrasound can also be used for image-guided interventions with fine-needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy. Ultrasound provides a guide if further imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging are required. ANATOMY OF THE PAROTID SPACE branches into the maxillary and superficial temporal arteries within the gland (Figs. 1 and 2). The parotid gland lies in the retromandibular fossa The parotid duct, or Stensen duct, exits the and is bordered posteriorly by the sternocleidomas- gland anteriorly, passes above the masseter mus- toid muscle and posteromedially by the mastoid cle, and perforates the buccal fat and buccinator process. The masseter and medial pterygoid mus- muscle to open into the oral cavity at the level of cles are located anteromedial to the gland, along the second upper molar. Accessory parotid tissue with the mandibular ramus. The gland consists of may be found along the course of the parotid duct, superficial and deep lobes, which are defined by arising in approximately 20% of the population.2 the path of the facial nerve traveling through the The parotid gland is predominantly a serous gland. -

Thesis, for Their Cooperation and Patience During the Various Tests for Which They Did Not Always See the Importance

UNIVERSITE DE GENEVE FACULTE DE MEDECINE Département des Neurosciences Cliniques Professeur P. Montandon et Dermatologie Clinique et Policlinique d'Oto-rhino- laryngologie et Chirurgie Cervico-Faciale Division de Chirurgie Cervico-Faciale Professeur W. Lehmann PAROTIDECTOMY COMPLICATIONS. NEW TECHNIQUES FOR THEIR OBJECTIVE EVALUATION, PREVENTION AND TREATMENT Travail présenté par le Docteur Pavel Dulguerov pour obtenir le titre de Privat Docent Genève 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of illustrations ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................... 7 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 13 1.1. History of parotid surgery ................................................................................................................ 14 1.2. Anatomy ............................................................................................................................................ -

Salivary Gland Tumors an Update

Salivary Gland Tumors An Update October 2019 Ian Pereira, MD Faculty Advisor: Dr. Timothy Owen, MD, FRCPC Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada Objectives Build on previous ARROCases for salivary gland tumors (SGTs)1 including benign & malignant disease: 1. Recognize the presentation of pleomorphic adenoma (PA) and carcinoma ex PA (CaXPA) 2. Develop a framework for managing benign & malignant SGTs 3. Understand the epidemiology, classification, & prognosis 4. Review relevant clinical trials A lump in the neck • 40-year-old aesthetician with a slowly growing mass in her neck over 3-4 months • No pain, trismus, facial weakness, numbness, dysphagia, or odynophagia • Physical exam with focus on the head & neck (H&N): – A 3cm, firm, nontender, mobile mass at the angle of the mandible – No other palpable masses or adenopathy – Cranial nerve exam is normal – Oral mucosa & skin are intact Referred to ENT • Ultrasound shows a single hypoechoic mass in the parotid with posterior acoustic enhancement • Fine Needle Aspiration & Biopsy (FNAB) consistent with pleomorphic adenoma (PA) • Superficial parotidectomy reveals a tumor in the superficial lobe of the parotid • Pathology shows PA with a ruptured capsule • Transient CN VII paralysis with recovery 4 months later • Discharged to her GP after 5 years of uneventful follow-up 2 2 5 Years Later… • She returns with a 2-year history of a mass in same location at the angle of the mandible • CT shows an enhancing mass adjacent to the residual deep lobe with necrosis • FNAB shows recurrent pleomorphic adenoma