Doctoral Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologischen Karte

Kennt ‚H149 fi/M W2 y fl Erläuterungen Geologischen Karte V011 Preußen und benachbarten Bundesstaaten. Herausgegeben von der Königlich Preußischen Geologischen Landesanstalt. Lieferung 187. Blatt Bröckel. Gradabteilung 41, Nr. 30. Geologisch und bodenkundlich bearbeitet durch E. Harhort, H. Monke und l. Stoller. Erläutert durch J. Stoller, der bodenkundliche Teil durch E.’Harhort. Mit einer Übersichtskarte. ~NVV\/\/\I\N\I\N\’W\I\N\M WAI\/W\N\4V\J\ I\/\/' BERLIN. Im Vertrieb bei der Königlichen Geologischen Landesanstalt Berlin N. 4, Invalidenstraße 44. 1916. g v- . fix-‘nv.1 J. m ‚P: h sie. 2’? iii ECA REG I A ALTE; mam. GEURGIAE AUG. Geologische Übersichtskarte der Gegend von Celle. ZF'eu' ee' ' ' 53h: Zeichen—Erklärung Tertiär Diluvium Ei-- JEpfan'ez: fan ‘ In fe-r;who! A”: es cigar 70!? Diluvium ‚i’ffdx‘ä Hocfifl Jung - a"?am: an a“ 212'ms?yawn- gamma: arejnfrei Heim“; Hochfläche gerjqd’äandb edeckung Diluvium TM: and 1'; (Shem qfé Haupfafufe ms?jüngeren [rosz'anssfufen A Huv iu rn Sand u. Sowie} Meere flänsn der gra Een #0:? großem Ffuffäfer Umfang Maßslab 1:200000 ._':;r_„._1.__:=—'x . :__.......—.-.*:.H. Q Fuhflbergf'l‘fir' .-—-——————.- i. Ir I A Lfi- .in:1, 3-5“ . 2lHr ifl' enlw. J.31ullar. Gegend von Celle. Lief. 187 und 191. sua Göttin 207 81 808 3 l Blatt Bröckel. Gradabteilung 41, Nr. 30. Geologisch und bodenkundlich bearbeitet durch E. Harbort, H. Monke und J. Stoller. Erläutert durch l. Stollor, der bodenkundliche Teil durch E. Harbort. ——.—.——— Mit l Übersichtskarte. Bekanntmachung. Jeder Erläuterung liegt eine »Kurze Einführung in das Verständnis der geologisch-agronomischen Karten<<, sowie ein Verzeichnis der bis- herigen Veröffentlichungen der Königlich Preußischen Geologischen Landesanstalt bei. -

Family Gender by Club MBR0018

Summary of Membership Types and Gender by Club as of November, 2013 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. Student Leo Lion Young Adult District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male Total Total Total Total District 111NW 21495 CLOPPENBURG 0 0 10 41 0 0 0 51 District 111NW 21496 DELMENHORST 0 0 0 36 0 0 0 36 District 111NW 21498 EMDEN 0 0 1 49 0 0 0 50 District 111NW 21500 MEPPEN-EMSLAND 0 0 0 44 0 0 0 44 District 111NW 21515 JEVER 0 0 0 42 0 0 0 42 District 111NW 21516 LEER 0 0 0 44 0 0 0 44 District 111NW 21520 NORDEN/NORDSEE 0 0 0 47 0 0 0 47 District 111NW 21524 OLDENBURG 0 0 1 48 0 0 0 49 District 111NW 21525 OSNABRUECK 0 0 0 49 0 0 0 49 District 111NW 21526 OSNABRUECKER LAND 0 0 0 35 0 0 0 35 District 111NW 21529 AURICH-OSTFRIESLAND 0 0 0 42 0 0 0 42 District 111NW 21530 PAPENBURG 0 0 0 41 0 0 0 41 District 111NW 21538 WILHELMSHAVEN 0 0 0 35 0 0 0 35 District 111NW 28231 NORDENHAM/ELSFLETH 0 0 0 52 0 0 0 52 District 111NW 28232 WILHELMSHAVEN JADE 0 0 1 39 0 0 0 40 District 111NW 30282 OLDENBURG LAPPAN 0 0 0 56 0 0 0 56 District 111NW 32110 VECHTA 0 0 0 49 0 0 0 49 District 111NW 33446 OLDENBURGER GEEST 0 0 0 34 0 0 0 34 District 111NW 37130 AMMERLAND 0 0 0 37 0 0 0 37 District 111NW 38184 BERSENBRUECKERLAND 0 0 0 23 0 0 0 23 District 111NW 43647 WITTMUND 0 0 10 22 0 0 0 32 District 111NW 43908 DELMENHORST BURGGRAF 0 0 12 25 0 0 0 37 District 111NW 44244 GRAFSCHAFT BENTHEIM 0 0 0 33 0 0 0 33 District 111NW 44655 OSNABRUECK HEGER TOR 0 0 2 38 0 0 0 40 District 111NW 45925 VAREL 0 0 0 30 0 0 0 30 District 111NW 49240 RASTEDE -

2021 Fahrplan Strecke RE2 (Hannover-Göttingen)

Neumünster Itzehoe Kiel Lübeck Husum Flensburg Puttgarden Westerland (Sylt) Kopenhagen Besser als jeder Anschluss! Büchen, Schwerin, Berlin cambio CarSharing-Station Hamburg Hbf Glockengießerwall RE4/RB41 RE3/RB31 Besser als jeder Anschluss! cambio CarSharing-Station Glockengießerwall Stade Cuxhaven Hamburg-Harburg Hittfeld Meckelfeld Besser als jeder Anschluss! Buchholz Maschen cambio CarSharing-Station Klecken (Nordheide) Glockengießerwall RB31 Stelle Ashausen Sprötze RE3 Winsen (Luhe) Tostedt Radbruch Lauenbrück BardowickBüchen, Lübeck, Kiel Besser als jeder Anschluss! Oldenburg Scheeßel Lüneburg cambio CarSharing-Station RB41 Glockengießerwall Wilhelmshaven Ottersberg (Han) Oberneuland Rotenburg RE4 Leer Bremen- Emden (Wümme) Sagehorn Sottrum Norddeich Bienenbüttel (Fähre Juist/ Bremer- Norderney) haven Besser als jeder Anschluss! cambio CarSharing-Station Bad Bevensen Bremen Hbf Soltau, Uelzen Verden Glockengießerwall RE4/RB41 (Aller) RE3 Osnabrück RB31 Verden (Aller) Besser als jeder Anschluss! Salzwedel cambio CarSharing-Station Uelzen Stendal Nienburg (Weser) Glockengießerwall Hannover Magdeburg RE3 Suderburg RE2 Unterlüß Eschede Celle Lehrte Hannover Hbf - Göttingen (RE2) Großburgwedel Baustellen-Übersicht RE2 den Harz im Blick zwischen Hannover und Göttingen Nienburg Minden Langenhagen Mitte Osnabrück Verden Bremen RE3 RE2 Berlin, Köln Hannover Hbf Leipzig Da kann man nix machen. Wenn die Deutsche Bahn baut, wird‘s auch für metronom Düsseldorf Frankfurt RE2 Kunden eng. Stuttgart Würzburg Unter anderem zu folgenden Zeiten wird es Abweichungen von dem vorliegenden München Jahresfahrplan geben. Tipp: Viele Züge fahren ab Hannover Sarstedt in Richtung Uelzen weiter, sodass du Baustellen-Service Grund Auswirkung bequem ohne Umstieg reisen kannst. Dies Nordstemmen Hildesheim Hannover Hbf - Göttingen - Arbeiten an Sicherungs- Hameln Elze (Han) 24.04. - 16.07.2021 leicht veränderte Fahrzeiten gilt natürlich auch in die entgegengesetzte Hannover Hbf RE2 anlagen Richtung. -

KSB Celle KSB Harburg-Land Sportbund Heidekreis Inhaltsverzeichnis

anerkannt für ÜL C Ausbildung KSB Celle KSB Harburg-Land Sportbund Heidekreis Inhaltsverzeichnis Hier sind alle Fortbildungen zu finden, die über die Sportbünde Celle, Harburg-Land und Heidekreis angeboten werden. Mit einem „Klick“ auf den Titel werden sie direkt zur entsprechenden Ausschreibung geleitet Sprache lernen in Bewegung-Elementarbereich 4 Spiel und Sport im Schwarzlichtmodus 5 Fit mit digitalen Medien 6 Sport und Inklusion 7 Kräftigen und Dehnen 8 Fit mit Ausdauertraining /Blended learning Format 9 Starke Muskeln-wacher Geist - Kids 10 Spielekiste und trendige Bewegungsangebote 11 Das Deutsche Sportabzeichen 12 #Abenteuer?-Kooperative Abenteuerspiele und Erlebnispädagogik 13 Spiel- und Sport für kleine Leute 14 Alles eine Frage der Körperwahrnehmung! 15 Trainieren mit Elastiband 16 Mini-Sportabzeichen 17 Spiele mit Ball für Kinder im Vorschulalter 18 Rund um den Ball 19 Fitball-Trommeln 20 Einführung in das Beckenbodentraining 21 Der Strand wird zur Sportanlage 22 Inhaltsverzeichnis Stärkung des Selbstbewusstsein und Schutz vor Gewalt im Sport 23 Einführung in die Feldenkraismethode 24 Natur als Fitness-Studio 25 Bewegt in kleinen Räumen und an der frischen Luft 26 Übungsvielfalt 27 Stabil und standfest im Alter 28 Sport und Inklusion 29 Kinder stark machen 30 Ausbildung ÜL C 31 Information und Anmeldung 32 Legende: LQZ sind kostenfreie Fortbildungen für Lehrer, Erzieher und ÜL im Rahmen des Aktionsprogramms „Lernen braucht Bewegung“. Diese Fortbildung ist im C 50-Flexbereich der ÜL C-Ausbildung Breitensport anerkannt. ÜL B Diese Ausbildung ist für ÜL B Prävention anerkannt. Sprache lernen ….. 16.00-19.15 Uhr (4 LE) Celle Kostenfrei/ LQZ Dr. Bettina Arasin Nr.: 2/32/13870 … in Bewegung für den Elementarbereich. -

Geologischen Karte

W/f‘f/é? Erläuterungen Geologischen Karte V011 Preußen und benachbarten Bundesstaaten. Herausgegeben von der Königlich Preußischen Geologischen Landesanstalt. Lieferung 18'7. Blatt Beedenbostol. Gradabteilung 41, Nr. 24. Geologisch und bodenkundlicb bearbeitet durch E. Harbort und J. Stoller. Erläutert durch E. Harbort. Mit einer Übersichtskarte und einer Abbildung im Text. \\1\1~ »\\/‘\,~1 I\(\\ \;\\V/ BEBLII Im Vertrieb bei der Königlichen Geologischen Landesanstalt Berlin N. 4, Invalidenstraße 44. 1916. Geologische Übersichtskarte der Gegend von Celle. 2?är 531v Zeichen-Erklärung Tertiär Diluvium [El-- JEpfarr-fenfan _ fnffirgfdzx'af fiese-{gar Ton Diluvium ‚r . f ‚Ffra’flf flach}?! Jung- Herman 1.2"mirgar-im dänn‘dfa Sier'nfrei aft-Fm} fiaohfl'äa‘w gerjunydandfiea’eckunyfl. Diluvium To!S an a’ Ä über? 5'm 1?Japanraft ms'fjfinyerm fromana'sfufEn A l I u v i u m .. '|. .I-I: .. I..r_ ‚W. Sand u. Schlick Meere 955m der freien ran lyre-Fem fiufifd‘fer Umfang 4 Maßeiab 1=2ooooo ‘ . - .- ä'. — "" — _- IH— r:.- I ’V-l52.5. Tr ' '3 “Ewmffir ‘_ “F ‘ .- "L” '5' _. — __ - ; {fr-5;;"' 3/ . .... ß2’ . ~//,‚1/ 'Öä/J’; ' z; " ‘_"_"_‚‘_“f . __________ -' 1'; '.' .'.‚ éz I; ‚ --""-„.‘-... ,7! 'g/e/flf’ Jg J r" f/x/ f “s M -C_J Eu H nb'efg" f' .I‘ :".‚.' . - .1 ——————— - . I: „I'- —————————‘i ._ - . " ****** e _ I... i I. lit-4'" :‘IH F‘— ——————— — ‘21 E‘L‘I. l’ r _ .51.“ _________ L21. Fr p...- 'I. 'I _ "'_ __ ' f. .‘.:.'..—"i’ I - I’HN \Z‘ +"j— I. I l _ Rm-I—fi—l—t—g'F-‘EF—‘r -- ‘+" :4‘" —'u I. -

Linie 44 Alfeld - Sibbesse - Hildesheim Gültig Ab 09.08.2018

RVHI Regionalverkehr Hildesheim GmbH Tel.: 05121 - 76420 www.rvhi-hildesheim.de Linie 44 Alfeld - Sibbesse - Hildesheim Gültig ab 09.08.2018 montags bis freitags sonnabends sonntags S S SX F S F S fr AST AST AST AST AST AST AST AST Ankunft Bahn aus Hannover 6:10 6:10 8:10 9:06 10:10 11:06 11:06 12:10 13:06 13:06 14:10 15:06 16:10 17:06 18:10 21:06 6:10 10:10 12:10 14:10 16:10 18:10 20:10 21:06 10:10 12:10 14:10 16:10 18:10 Alfeld / Bahnhof-ZOB 5:20 6:20 6:20 7:40 8:20 9:20 10:20 11:20 11:20 12:20 13:20 13:20 14:20 15:20 16:20 17:20 18:20 21:20 6:20 7:40 10:20 12:20 14:20 16:20 18:20 20:20 21:20 10:20 12:20 14:20 16:20 18:20 Alfeld / Perkwall / Sparkasse 5:22 6:22 6:22 7:42 8:22 9:22 10:22 11:22 11:22 12:22 13:22 13:22 14:22 15:22 16:22 17:22 18:22 21:22 6:22 7:42 10:22 12:22 14:22 16:22 18:22 20:22 21:22 10:22 12:22 14:22 16:22 18:22 Alfeld / Perkwall / Sedanstraße 5:24 6:24 6:24 7:44 8:24 9:24 10:24 11:24 11:24 12:24 13:24 13:24 14:24 15:24 16:24 17:24 18:24 21:24 6:24 7:44 10:24 12:24 14:24 16:24 18:24 20:24 21:24 10:24 12:24 14:24 16:24 18:24 Alfeld / Alter Friedhof 5:26 6:26 6:26 7:46 8:26 9:26 10:26 11:26 11:26 12:26 13:26 13:26 14:26 15:26 16:26 17:26 18:26 21:26 6:26 7:46 10:26 12:26 14:26 16:26 18:26 20:26 21:26 10:26 12:26 14:26 16:26 18:26 Alfeld / Senator Behrens Straße 5:27 6:27 6:27 7:47 8:27 9:27 10:27 11:27 11:27 12:27 13:27 13:27 14:27 15:27 16:27 17:27 18:27 21:27 6:27 7:47 10:27 12:27 14:27 16:27 18:27 20:27 21:27 10:27 12:27 14:27 16:27 18:27 Langenholzen 5:29 6:29 6:29 7:49 8:29 9:29 10:29 11:29 11:29 12:29 13:29 13:29 -

3.3. the Indicator Kriging (IK) Analyses for the Göttingen Test Site

Geostatistical three-dimensional modeling of the subsurface unconsolidated materials in the Göttingen area: The transitional-probability Markov chain versus traditional indicator methods for modeling the geotechnical categories in a test site Dissertation Submitted as a partial fulfilment for obtaining the “Philosophy doctorate (Ph.D.)" degree in graduate program of the Applied Geology department, Faculty of Geosciences and Geography, Georg-August-University School of Science (GAUSS), Göttingen Submitted by (author): Ranjineh Khojasteh, Enayatollah Born in Tehran, Iran Göttingen , Spring 2013 Geostatistical three-dimensional modeling of the subsurface unconsolidated materials in the Göttingen area: The transitional-probability Markov chain versus traditional indicator methods for modeling the geotechnical categories in a test site Dissertation zur Erlangung des mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades " Philosophy doctorate (Ph.D.)" der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen im Promotionsprogramm Angewandte Geoliogie, Geowissenschaften / Geographie der Georg-August University School of Science (GAUSS) vorgelegt von Ranjineh Khojasteh, Enayatollah aus (geboren): Tehran, Iran Göttingen , Frühling 2013 Betreuungsausschuss: Prof. Dr. Ing. Thomas Ptak-Fix, Prof. Dr. Martin Sauter, Angewandte Geologie, Geowissenschaftliches Zentrum der Universität Göttingen Mitglieder der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Ing. Thomas Ptak-Fix, Prof. Dr. Martin Sauter, Angewandte Geologie, Geowissenschaftliches Zentrum der Universität Göttingen Referent: Prof. -

Der LÖSCHEIMER Zeitung Der Kreisjugendfeuerwehr Lüneburg

der LÖSCHEIMER Zeitung der Kreisjugendfeuerwehr Lüneburg Ausgabe Nr. 46/ 24. Jahrgang INHALT Hallo! Dies ist nun also Löscheimer Nr. 46! Inhalt In neuer Aufmachung, aber mit stets bewährten Themen: Ausflüge & Unternehmungen, Versammlungen, Ausflüge & Unternehmungen sowie Ausbildung & Prüfungen. Hört sich 3 Herbstprogramm der SG-JF Gellersen alles etwas trocken an, ist es aber nicht! 4 Der fröhliche Weihnachtsmarkt in Dahlenburg/ Ein Baum Wie ihr vielleicht schon am Deckblatt für die Zukunft gesehen habt, ist diese Ausgabe nun also 5 Feuerwehr sportlich/ Bouldern im Kraftwerk mit neuer “Handschrift“ gestaltet. Natascha Brassat, die seit Jahren für diese 6 Oh Tannebaum in Amelinghausen Zeitung stand, hat die Aufgabe des 7 Nikolaus bei der Feuerwehr in Bleckede & Lüneburg/ Layouts nun an mich übergeben und ich Halloween der JF Rettmer werde sehen, wohin uns das gestalterisch 8 Baumpflanzen in Lüneburg/ Umwelttag führt… Das perfekte Layout habe ich für mich noch nicht gefunden, aber ich 9 Neues Fahrzeug für Partnerwehr/ Impressum werde fleißig daran arbeiten ;-). Gerne 10 Nacht-O-Marsch in Brietlingen nehme ich dazu auch eure Ideen 11 Reppenstedter Nachtmarsch/ Wintervergleichswettbewerb entgegen… in Barum Ein paar Dinge sind mir aufgefallen: Nicht 12 Orientierungsmarsch in Reppenstedt jeder Bericht ist bei mir mit Datum und 13 Orientierungsmarsch in Radegast/ Autor angekommen. Zudem ist nicht 33. Garlsdorfer Zehnkampf immer ersichtlich, wer die Fotos gemacht hat- ich habe dann jeweils die JF Extra angenommen. Am auffälligsten war 14 Rätsel -

Documentation Centre

Lower Saxony Memorials Foundation Permanent Exhibition Documentation Centre Bergen-Belsen Memorial The three-part exhibition in the Memorial’s Open daily Documentation Centre, which opened in 2007, April to September 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. explains the history of the Bergen-Belsen, Wehrmacht POW Camp Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp October to March 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. Documentation Centre Fallingbostel, Oerbke and Wietzendorf POW Ground floor 1939 – 1945 1943 – 1945 The Documentation Centre is closed over the camps (1939 – 1945) as well as Bergen-Belsen’s New Year period. The precise dates can be history as a concentration camp (1943 – 1945) Entrance Prologue Film tower Archaeological finds Topography found on our website. Entry is free of charge. and displaced persons camp (1945 – 1950). The exhibition features numerous documents, Book Shop photographs, films and artefacts from national Car park The book shop is open during the Documen- and international archives, private owners and tation Centre’s opening hours and offers a the Memorial’s own extensive collection. The diverse selection of accounts and witness perspectives of victims and survivors are reports in different languages. represented throughout the exhibition through diaries, letters, drawings, personal accounts Library and witness interviews. Short explanatory texts Monday, Tuesday and Thursday on the wall panels place these sources in a Friedhof 10.30 a.m. – 4.30 p.m. historical context. Historisches Lagergelände and by appointment Video Points 1, 2 3 6 3 Cafeteria The video points show 45 films which were Supplementary levels Soviet POWs Soviet POWs Liberation Men’s and women’s camps April to September 10 a.m. -

FAHRPLAN 2021 Nur Solange Der Vorrat Reicht

FAHRPLAN 2021 FAHRPLAN 2021 gültig ab 13.12.2020 Nur solange der Vorrat reicht. RE4 RB41 RE3 RB31 RE2/RE3 RE2 Bremen Hbf Bremen Hbf Uelzen Uelzen Uelzen Göttingen Zug fahren ist einfach und sicher Bremen- Nörten- Oberneuland Bad Bevensen Bad Bevensen Suderburg Hardenberg Sagehorn Trag‘ einen Mund-Nasen-Schutz, Bienenbüttel Bienenbüttel Northeim Ottersberg (Han) halte Abstand, kauf‘ eine Fahrkarte! Lüneburg Lüneburg Unterlüß Einbeck- Sottrum Salzderhelden Rotenburg Rotenburg Bardowick (Wümme) (Wümme) Eschede Kreiensen Fahrkarten Radbruch Scheeßel Freden (Leine) Lauenbrück Winsen (Luhe) Winsen (Luhe) Celle Alfeld (Leine) Tostedt Tostedt Ashausen Großburg- Sprötze wedel Banteln Abstand Maske tragen, Erst aussteigen, Fahrkarte kaufen Stelle Buchholz Buchholz auch im Bahnhof dann einsteigen (Nordheide) (Nordheide) Elze (Han) Maschen Isernhagen Klecken Nordstemmen Meckelfeld Aus Respekt vor anderen Fahrgästen: Hittfeld Langenhagen Das Tragen eines Mund-Nasen-Schutzes ist in öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln Hamburg- Hamburg- Hamburg- Hamburg- Mitte Sarstedt während der gesamten Fahrt vorgeschrieben. Ohne Maske dürfen wir dich Harburg Harburg leider nicht mitnehmen. Harburg Harburg Hamburg Hbf Hamburg Hbf Hamburg Hbf Hamburg Hbf Hannover Hbf Hannover Hbf Schön, dass du da bist! Unterwegs mit Freunden – RE4/RB41 Hamburg – Rotenburg – Bremen S. 8 RE3/RB31 Hamburg – Lüneburg – Uelzen S. 34 unser Service für dich! RE2/RE3 Hannover – Celle – Uelzen S. 60 In diesem Jahresfahrplan findet ihr alle Verbindungen, die ihr auf dem Weg zur Arbeit, zur RE2 Hannover – Northeim – Göttingen S. 74 Die Familie oder zu Freunden benötigt. Die besten Ausflugstipps mit dem metronom findet ihr METRONOM auf unserer Website unter www.metronom.de Aktuelle Verkehrsmeldungen und mehr APP RE4/RB41: facebook.com/metronom.RE4.Hamburg.Rotenburg.Bremen RE3/RB31: facebook.com/metronom.RE3.Hamburg.Lueneburg.Uelzen RE2: facebook.com/metronom.RE2.Uelzen.Hannover.Goettingen Sardinen-Züge Diese Züge RE2: facebook.com/metronom.RE2.Uelzen.Hannover.Goettingen sind sehr voll. -

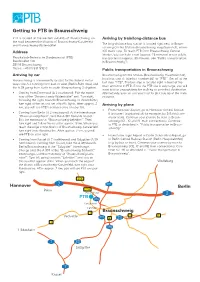

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig PTB is located on the western outskirts of Braunschweig, on Arriving by train/long-distance bus the road between the districts of Braunschweig-Kanzlerfeld The long-distance bus station is located right next to Braun- and Braunschweig-Watenbüttel. schweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), where Address ICE trains stop. To reach PTB from Braunschweig Central Station, you can take a taxi (approx. 15 minutes) or use public Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) transportation (approx. 30 minutes, see “Public transportation Bundesallee 100 in Braunschweig”). 38116 Braunschweig Phone: +49 (0) 531 592-0 Public transportation in Braunschweig Arriving by car Braunschweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), local bus stop A: take bus number 461 to “PTB”. Get off at the Braunschweig is conveniently located for the federal motor- last stop “PTB”. The bus stop is located right in front of the ways: the A 2 running from east to west (Berlin-Ruhr Area) and main entrance to PTB. Since the PTB site is very large, you will the A 39 going from north to south (Braunschweig-Salzgitter). want to plan enough time for walking to your final destination. • Coming from Dortmund (A 2 eastbound): Exit the motor- Alternatively, you can ask your host to pick you up at the main way at the “Braunschweig-Watenbüttel” exit. Turn right, entrance. following the signs towards Braunschweig. In Watenbüttel, turn right at the second set of traffic lights. After approx. 2 Arriving by plane km, you will see PTB‘s entrance area on your left. • From Hannover Airport, go to Hannover Central Station • Coming from Berlin (A 2 westbound): At the interchange (Hannover Hauptbahnhof) for example, by S-Bahn (com- “Braunschweig-Nord”, take the A 391 towards Kassel. -

Endrunde Avacon-Cup 2017(1)

Niedersächsischer Fußballverband U13 Avacon-Cup Montag, den 12.06.2017 - Dienstag, den 13.06.2017 August-Wenzel-Stadion - Kirchdorfer Str. 15, 30890 Barsinghausen Uhrzeit: 15:30 Uhr Spielzeit:1 x 15 min 1. Tag Wechselzeit: 1 min Uhrzeit: 09:30 Uhr Spielzeit:1 x 15 min 2. Tag Wechselzeit: 1 min Mannschaften Mannschaften Mannschaften Aurich Leer/Emden Oldenburg-Land/Delmenhorst Rotenburg Diepholz Hannover 96 Lüneburg/Lüchow-Dannenberg VfL Osnabrück VfL Wolfsburg Bentheim Spielplan: Nr. Pl. Uhrzeit Spielpaarung Ergebnis 1 1 15:30 Aurich - Bentheim 2 : 0 2 2 15:30 Oldenburg-Land/Delmenhorst - VfL Osnabrück 2 : 0 3 1 15:46 Diepholz - Hannover 96 1 : 1 4 2 15:46 Lüneburg/Lüchow-Dannenberg - Rotenburg 1 : 0 5 1 16:02 VfL Wolfsburg - Leer/Emden 1 : 1 6 2 16:02 Bentheim - Oldenburg-Land/Delmenhorst 0 : 3 7 1 16:18 Aurich - Diepholz 1 : 1 8 2 16:18 VfL Osnabrück - Lüneburg/Lüchow-Dannenberg 2 : 1 9 1 16:34 Hannover 96 - VfL Wolfsburg 1 : 0 10 2 16:34 Leer/Emden - Rotenburg 0 : 1 11 1 16:50 Diepholz - Bentheim 1 : 0 12 2 16:50 Oldenburg-Land/Delmenhorst - Lüneburg/Lüchow-Dannenberg 1 : 2 13 1 17:06 VfL Wolfsburg - Aurich 2 : 1 14 2 17:06 VfL Osnabrück - Leer/Emden 3 : 1 15 1 17:22 Rotenburg - Hannover 96 0 : 0 16 2 17:22 Lüneburg/Lüchow-Dannenberg - Bentheim 3 : 0 17 1 17:38 Diepholz - VfL Wolfsburg 0 : 0 18 2 17:38 Leer/Emden - Oldenburg-Land/Delmenhorst 1 : 0 19 1 17:54 Aurich - Rotenburg 0 : 1 20 2 17:54 Hannover 96 - VfL Osnabrück 0 : 0 21 1 18:10 Bentheim - VfL Wolfsburg 0 : 3 22 2 18:10 Lüneburg/Lüchow-Dannenberg - Leer/Emden 2 : 0 23 1 18:26 Rotenburg - Diepholz 0 : 1 24 2 18:26 Oldenburg-Land/Delmenhorst - Hannover 96 0 : 1 25 1 18:42 VfL Osnabrück - Aurich 1 : 1 Niedersächsischer Fußballverband U13 Avacon-Cup Montag, den 12.06.2017 - Dienstag, den 13.06.2017 August-Wenzel-Stadion - Kirchdorfer Str.