The Best Way to Locate a Purpose in Sport in Defence of a Distinction for Aesthetics?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essential Soccer Skills

Individual Skills 60 INDIVIDUAL SKILLS Anatomy of a player Like dancers and singers, soccer players’ bodies are their instruments, their means of performance and expression. Although professionals are generally getting taller and increasingly fitter, the game still offers space for a variety of physiques and specialisms. Key requirements | ANATOMY OF A PLAYER Although players vary in size and Eyes shape, all top-level players have certain Players need to anatomical requirements in common. read the game and judge speeds Strong leg muscles—the calf, thigh and distances muscles, and hamstrings—are the most important. Good upper-body strength is also vital. Deltoids These muscles power the arms and are useful for cushioning high balls Chest muscles This muscle group helps players to run and pass Abdominals Core inner-body strength is a prerequisite of the balance and posture required for top-level soccer Quadriceps The four muscles at the front of the thigh are the soccer player’s engine room, essential for running and kicking Groin Takes much of Ankles the muscle Must be stress caused strong to cope by shooting, with the stress so pre-match of constant stretching is vital changes of direction ,, NECK 61 A PLAYER’S INDIVIDUAL SKILLS MUSCLES ARE THE KEY ,,TO POWERFUL HEADING. BODY STRENGTH A player’s leg muscles do much of the work (and are the most | prone to injury), but a strong ANATOMY OF A PLAYER neck, spine, chest, abdominals, and deltoids are all important. Neck muscles The key to powerful heading, players need to work specifically on these muscles to strengthen them Spine Liable to take a lot of stress in a match, as a player braces and stretches for every turn Hamstrings Give flexibility to the knee and hip and allow the leg to stretch. -

Johan Cruyff Game Changer

JOHAN CRUYFF GAME CHANGER Cruyff for the Netherlands. Photo: Nationaal Archief Cruyff for Ajax (right) against Feyenoord, September 1967. Photo: Nationaal Archief Jon Hoggard Winner of the Ballon d’Or an incredible three times, Cruyff started his footballing career at Ajax, where he led the Dutch giants to 23 eight league titles and three consecutive It is difcult to overstate just European Cups in 1971, 1972 and 1973. how much of an infuence Dutch football legend Johan Cruyf has had on the sport. Winner of the Ballon d’Or an incredible In the early 1970s came the incredible three times, Cruyf started his run of three consecutive European From his time on the pitch, footballing career at Ajax, where he Cup wins between 1971 and 1973, starring for Ajax, Barcelona led the Dutch giants to eight league with Cruyf scoring twice in the fnal and the Dutch national side, titles and three consecutive European of the 1972 competition against to his time in management Cups. He joined the club aged 10, Internazionale. In 1971 Johan had been and was a talented baseball player named as European Footballer of the at the same institutions, alongside his football development Year. Cruyf has always been at until he decided to concentrate on Following the 1973 European Cup the cutting edge of football football at age 15. He frst established win, Johan moved to Barcelona in a development. himself in the Ajax frst team aged 18 in world record-breaking transfer. He 1965–66, a season in which he scored immediately made an impact and 25 goals in 23 games as Ajax won the helped the Catalans to their frst league championship. -

Goalden Times: October, 2011 Edition

Goalden Times October 2011 Page 0 qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyu Goalden Times Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: GOALden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes October 2011 Page 1 Goalden Times | Edition III | First Whistle…………4 Goalden Times is a ‘rising star’. Watch this space... Garrincha – The Forgotten Legend …………5 Deepanjan Deb pays a moving homage to his hero in the month of his birth Last Rays of Sunshine Before the Clouds of War…………9 In our Retrospective feature - continuing our journey through the history of the World Cup, Kinshuk Biswas goes back to the last World Cup before World War II 1911 – A Seminal Win …………16 Kaushik Saha travels back in time to see how a football match influences a nation’s fight for freedom Amarcord: My Life as a Calcio Fan…………20 We welcome Annalisa D’Antonio to share her love of football and growing up stories of fun, frolic and Calcio This Month That Year…………23 This month in Football History Rifle, Regime, Revenge and the Ugly Game…………27 Srinwantu Dey captures a vignette of stories where football no longer remained ‘the beautiful game’ Scouting Network…………33 A regular feature - where we profile an upcoming talent of the football world. -

Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions Vol 1

This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions Vol 1 By Dan Brown Published by WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) First published September, 2019 by WORLD CLASS COACHING 3404 W. 122nd Leawood, KS 66209 (913) 402-0030 Copyright © WORLD CLASS COACHING 2019 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Author – Dan Brown Edited by Tom Mura Front Cover Design – Barrie Bee Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions I 1 ©WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) Table of Contents 3 Overview and Itinerary 8 Opening Presentation with Harry Jensen, KNVB 10 Notes from Visit to ESA Arnhem Rijkerswoerd Youth Club 12 Schalke ’04 Stadium and Training Complex Tour 13 Ajax Background 16 Training Session with Harry Jensen, KNVB 19 Training Session with Joost van Elden, Trekvogels FC 22 Ajax Youth Team Sessions 31 Ajax U13 Goalkeeper Training 34 Ajax Reserve Game & Attacking Tendencies Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions I 2 ©WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. -

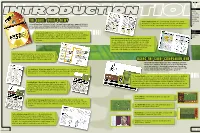

Introduction

INTRODUCTION HOW TO PLAY COACHING MANUAL INTRODUCTION SECRET MOVES & TRICKS TACTICS & STRATEGIES MASTER LEAGUE THE GUIDE: WHAT’S NEW? Master League (page 82): An accessible yet deep guide to Pro Evo’s primary TEAM & PLAYER GUIDE single-player mode, this chapter also reveals a huge selection of the finest transfer EXTRAS In a word? Everything. Pro Evolution Soccer 6: The Expert Guide is an all-new companion to PES6, with targets available in PES6, from promising youngsters to world-class stars. INDEX a focus on ease of use and professional-level advice. For readers familiar with last year’s Pro Evolution Soccer 5 guide, we’ve prepared the following introduction to some of the key new features. WHAT’S NEW? Guide Companion DVD: With over 150 moves, tricks and techniques to view, the Guide USING THE DVD Companion DVD is an invaluable accompaniment to the guidance offered in the Coaching Manual PES6: NEW FEATURES and Secret Moves & Tricks chapters. With real-time executions of every move and onscreen EXPERT TIPS demonstrations of button commands, it makes the process of learning new techniques much, Team & Player Guide (page 100): Featuring 23 national and international much easier. sides, plus the Master League Default Team, the Team & Player Guide tells you everything you need to know about PES6’s best sides. With recommended formations, tips on strengths and weaknesses, and unbelievably detailed player tables – including unique special moves – this exhaustively researched chapter is designed to help you take your understanding of Pro Evolution 6 to an entirely new level. How to Play (page 8): We’ve included a very short chapter to help Pro Evo newcomers to get started, but don’t expect a blow-by-blow account of every available option – this is, after all, the Expert Guide. -

This Ebook Has Been Licensed To: Mohd Tarmizi ([email protected])

This ebook has been licensed to: Mohd Tarmizi ([email protected]) If you are not Mohd Tarmizi please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Mohd Tarmizi ([email protected]) Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions Vol 1 By Dan Brown Published by WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Mohd Tarmizi please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Mohd Tarmizi ([email protected]) First published September, 2019 by WORLD CLASS COACHING 3404 W. 122nd Leawood, KS 66209 (913) 402-0030 Copyright © WORLD CLASS COACHING 2019 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Author – Dan Brown Edited by Tom Mura Front Cover Design – Barrie Bee Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions I 1 ©WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Mohd Tarmizi please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Mohd Tarmizi ([email protected]) Table of Contents 3 Overview and Itinerary 8 Opening Presentation with Harry Jensen, KNVB 10 Notes from Visit to ESA Arnhem Rijkerswoerd Youth Club 12 Schalke ’04 Stadium and Training Complex Tour 13 Ajax Background 16 Training Session with Harry Jensen, KNVB 19 Training Session with Joost van Elden, Trekvogels FC 22 Ajax Youth Team Sessions 31 Ajax U13 Goalkeeper Training 34 Ajax Reserve Game & Attacking Tendencies Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions I 2 ©WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Mohd Tarmizi please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. -

Home Technial Programme After School

AFTER SCHOOL FOOTBALL HOME TRAINING PROGRAMME TECHNICAL PRACTICES facebook.com/afterschoolfootball afterschoolfootball.com [email protected] TECHNICAL PRACTICES EQUIPMENT • Footballs/ Tennis Balls/ Balloons /Rolled up socks • Players: Garden Furniture chairs/poles • Targets - Toys • Goals - washing basket/ buckets/jumpers • All practices to be done with both feet. • Experiment with all practices, try with different part of the body. • Some practices have a few ideas for games the players can try out • Kids don’t need help when it comes to using their imagination. So if a player is already out with a football they will be coming up with plenty of ways to practice from kicking a ball off the wall, up in the air or recreating their favourite goal. https://www.instagram.com/afterschoolfootball/ AFTER SCHOOL FOOTBALL HOME TRAINING PROGRAMME BALL MASTERY TECHNICAL PRACTICES Ball Mastery Toe Taps • Start with the sole of 1 foot on the ball and the other planted on the floor, • once you are balanced - switch positions. Repeat on the move. Sole Rolls • Push the ball softly with the sole of your foot, • Push the ball again with the sole of your other foot. • This can be done in any direction. Inside Outside • Start with the ball on one leg, push the ball forward with the inside of your foot, • Follow the ball and push it next with the outside of the same foot. • Repeat. TECHNICAL PRACTICES Cruyff Turn • Approach the ball as if you're going to shoot or pass. • Place your standing foot slightly in front of the ball, allowing space for you to push the ball behind your leg. -

How Italian Football Creates Italians: the 1982 World Cup, the ‘Pertini Myth’ and Italian National Identity

Foot, J. (2016). How Italian Football Creates Italians: The 1982 World Cup, the ‘Pertini Myth’ and Italian National Identity. International Journal of the History of Sport, 33(3), 341-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2016.1175440 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/09523367.2016.1175440 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Taylor & Francis at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09523367.2016.1175440. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 How Italian Football Creates Italians: The 1982 World Cup, the ‘Pertini Myth’ and Italian National Identity John Foot To cite this article: John Foot (2016) How Italian Football Creates Italians: The 1982 World Cup, the ‘Pertini Myth’ and Italian National Identity, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 33:3, 341-358, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2016.1175440 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2016.1175440 © 2016 The Author(s). -

Soccercoachinginternational's Glossary of Soccer Terms

SoccerCoachingInternational’s Glossary of Soccer Terms # 1 + 1 (2 + 2, 3 + 3, etc.) - a training situation in which both sides have the given number of players and the coach makes suggestions as play continues 1 v 1 (2 v 2, 3 v 3, etc.) - a competition or game in which both sides have the given number of players 1-Man System - a system of refereeing in which a single official controls the game from within the field, without use of assistant referees 1-Touch - a style of play in which the ball is passed on or distributed without touching the ball more than once 12th Man - the fans, supporters, and crowd that helps the home team gain an advantage over the visiting team 18-Yard Box - (British) - the penalty area; the large box adjacent to the goal mouth, extending 18 yards out into the field from the goal line and 18 yards in each direction from the goal posts to towards the corners 2-Man System - a system of refereeing in which two officials control the game from the sidelines 2-on-1 Break - 2 attacking players breaking against 1 defensive player 2-Touch - a style of play in which the ball is passed on or distributed after only two touches 2-3-5 - formation featuring 2 fullbacks, 3 halfbacks and 5 forwards, developed by the British in the 1890's and used until the 1940s; also known as the Pyramid Formation 3 D's of Defense - deny, delay, and destroy 3-Touch - a style of play in which the ball is passed on or distributed after only three touches 3-on-1 Break - a break with 3 attacking players against only 1 defensive player 3-on-2 Break - a break with 3 attacking players against 2 defensive players 3-5-2 - a formation featuring a goalkeeper, a sweeper and two marking backs, five midfielders and two forwards 3-4-3 - a rarely played formation, most often employed when a team is behind in a game and needs a goal. -

Essential Soccer Skills Celebrates the Sport by Presenting Its Varied and Complex Skills in a Clear and Simple Way

essential Learn how to master the key skills and techniques of the world’s most popular sport with this essential guide to soccer. SOCCER Explains the laws, tactics, and science behind the world’s most popular game Features detailed step-by-step illustrations to help perfect your skills SOCCER Describes the key tricks and techniques, from stops and turns to stepovers and set plays Profiles the individual skills used by legendary players, such as Cristiano Ronaldo and David Beckham Key tips and techniques Includes the concepts, formations, and strategies to improve your Game behind effective teamwork Includes content previously published in The Soccer Book Cover images: Background: iStockphoto.com: Max Delson Martin Santos. Front: Getty Images: AFP skills Other image © Dorling Kindersley. For further information see: www.dkimages.com $14.95 USA $16.95 Canada Printed in China Discover more at www.dk.com SOCCER SOCCER KEY TIPS AND TECHNIQUES TO IMPROVE YOUR GAME Includes content previously published in The Soccer Book LONDON, NEW YORK, MUNICH, MELBOURNE, and DELHI Senior Editor Bob Bridle Senior Art Editor Sharon Spencer Production Editor Tony Phipps Production Controller Louise Minihane Jacket Designer Mark Cavanagh Managing Editor Stephanie Farrow Managing Art Editor Lee Griffiths US Editor Margaret Parrish DK INDIA Managing Art Editor Ashita Murgai Editorial Lead Saloni Talwar Senior Art Editor Rajnish Kashyap Project Designer Anchal Kaushal Project Editor Garima Sharma Designers Amit Malhotra, Diya Kapur Editors Shatarupa Chaudhari, Karisma Walia Production Manager Pankaj Sharma DTP Manager Balwant Singh Senior DTP Designer Harish Aggarwal DTP Designers Shanker Prasad, Bimlesh Tiwari, Vishal Bhatia, Jaypal Singh Chauhan Managing Director Aparna Sharma First American Edition, 2011 Published in the United States by DK Publishing 375 Hudson Street New York, New York 10014 11 12 13 14 15 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 001—176109—Mar/2011 Includes content previously published in The Soccer Book Copyright © 2011 Dorling Kindersley Limited All rights reserved. -

Common Soccer Terminology

Common Soccer Terminology -- A -- Advantage rule - A clause in the rules that allows the referee to refrain from stopping play for a foul if a stoppage would benefit the team that committed the violation. See "Play on". Assist - the pass or passes that precede a goal. A maximum of two assists can be allocated for one goal. Attacking midfielder - the most forward-playing midfielder, playing right behind the forwards; he supports the offense by providing passes to forwards to set up goals. "Away" - clear the ball out of the area it is in, usually the Penalty Area (PA) -- B -- Back - a defender. Back heel - A ball played with the back of the foot to a teammate. Back tackle - An attempt by a defender to take the ball away from a ball carrier by swinging the defender's leg in front of the ball from behind. This is an illegal tackle and could result in carding or a free kick. Banana Kick - A kick (usually a long corner kick) that curves so much that it take the shape of a banana. The idea is to curve the ball from the corner directly into the goal. Bending Runs - runs made by players on the team with the ball that are not straight. If you run straight down the field in front of a teammate you can not receive a pass since your back is to the passer. By making a bending run you are always in a position "open" to a pass. Bending the ball - Striking the ball with an off-center kick so that it travels in a curved path; also known as a banana kick. -

Lessons and Inspiration for Business from the Life of Johan Cruyff

Lessons and inspiration for business from the life of Johan Cruyff A five step blueprint for values, culture and behaviours in your own business On March 24th 2016, the legendary footballer and manager, Johan Cruyff, passed away. To many he belongs among the hallowed quartet of truly exceptional individuals who have played the game: Pelé, Diego Maradona and Alfredo Di Stéfano. These are players who somehow transcended their sport to become household names and globally renowned superstars, adored by their countrymen and an inspiration to millions. In this Point of View, we examine five aspects of Johan Cruyff’s career that could act as a five step blueprint for values, culture and behaviours in your own business. 1. Start with a vision, then create a philosophy with a clear set of shared values The 1962 European Cup final in Amsterdam between Benfica and Real Madrid was a defining moment in the life of Johan Cruyff. At the age of fifteen, as a ball boy at the final, Cruyff witnessed first-hand the vision, stamina and relentless untracked movement of the great Alfredo Di Stéfano. Cruyff had an epiphany. He believed he had seen a vision for how the game of football should be played. Several years later, Johan Cruyff was to turn this vision into the revolutionary style of play known as ‘total football’, a completely fluid approach where no player occupies a fixed outfield role and any player can adopt another’s position in an instant. Critics argued that this was an unrealistic strategy on the pitch but those with such a viewpoint did not understand the essence of total football.