Shipping US Crude Oil by Water: Vessel Flag Requirements and Safety Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Merchant Marine

“China’s Merchant Marine” A paper for the China as “Maritime Power” Conference July 28-29, 2015 CNA Conference Facility Arlington, Virginia by Dennis J. Blasko1 Introductory Note: The Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook defines “merchant marine” as “all ships engaged in the carriage of goods; or all commercial vessels (as opposed to all nonmilitary ships), which excludes tugs, fishing vessels, offshore oil rigs, etc.”2 At the end of 2014, the world’s merchant ship fleet consisted of over 89,000 ships.3 According to the BBC: Under international law, every merchant ship must be registered with a country, known as its flag state. That country has jurisdiction over the vessel and is responsible for inspecting that it is safe to sail and to check on the crew’s working conditions. Open registries, sometimes referred to pejoratively as flags of convenience, have been contentious from the start.4 1 Dennis J. Blasko, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), a Senior Research Fellow with CNA’s China Studies division, is a former U.S. army attaché to Beijing and Hong Kong and author of The Chinese Army Today (Routledge, 2006).The author wishes to express his sincere thanks and appreciation to Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, U.S. Navy (Ret), for his guidance and patience in the preparation and presentation of this paper. 2 Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: Merchant Marine,” The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2108.html. According to the Factbook, “DWT or dead weight tonnage is the total weight of cargo, plus bunkers, stores, etc., that a ship can carry when immersed to the appropriate load line. -

Dredging and Disposal Plan

DREDGING AND DISPOSAL PLAN PORT OF OLYMPIA MARINE BERTHS 2 & 3 INTERIM ACTION DREDGING Contract No.: 2008-0011 Project No. MT0601 Submitted To: Port of Olympia Attn: Rick Anderson 915 Washington Street NE Olympia, WA TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Dredging ..................................................................................................................... 1 Trans-loading ............................................................................................................. 1 Material Barge ............................................................................................................ 2 Dredge Bucket ............................................................................................................ 3 Dredge Sediment Disposal ........................................................................................ 3 Working Hours .......................................................................................................... 3 Position & Progress Surveys .................................................................................... 3 Dredge Navigation ...................................................................................................... 4 Survey Boat ................................................................................................................ 4 Water Quality BMP’s ................................................................................................ -

Malacca-Max the Ul Timate Container Carrier

MALACCA-MAX THE UL TIMATE CONTAINER CARRIER Design innovation in container shipping 2443 625 8 Bibliotheek TU Delft . IIIII I IIII III III II II III 1111 I I11111 C 0003815611 DELFT MARINE TECHNOLOGY SERIES 1 . Analysis of the Containership Charter Market 1983-1992 2 . Innovation in Forest Products Shipping 3. Innovation in Shortsea Shipping: Self-Ioading and Unloading Ship systems 4. Nederlandse Maritieme Sektor: Economische Structuur en Betekenis 5. Innovation in Chemical Shipping: Port and Slops Management 6. Multimodal Shortsea shipping 7. De Toekomst van de Nederlandse Zeevaartsector: Economische Impact Studie (EIS) en Beleidsanalyse 8. Innovatie in de Containerbinnenvaart: Geautomatiseerd Overslagsysteem 9. Analysis of the Panamax bulk Carrier Charter Market 1989-1994: In relation to the Design Characteristics 10. Analysis of the Competitive Position of Short Sea Shipping: Development of Policy Measures 11. Design Innovation in Shipping 12. Shipping 13. Shipping Industry Structure 14. Malacca-max: The Ultimate Container Carrier For more information about these publications, see : http://www-mt.wbmt.tudelft.nl/rederijkunde/index.htm MALACCA-MAX THE ULTIMATE CONTAINER CARRIER Niko Wijnolst Marco Scholtens Frans Waals DELFT UNIVERSITY PRESS 1999 Published and distributed by: Delft University Press P.O. Box 98 2600 MG Delft The Netherlands Tel: +31-15-2783254 Fax: +31-15-2781661 E-mail: [email protected] CIP-DATA KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, Tp1X Niko Wijnolst, Marco Scholtens, Frans Waals Shipping Industry Structure/Wijnolst, N.; Scholtens, M; Waals, F.A .J . Delft: Delft University Press. - 111. Lit. ISBN 90-407-1947-0 NUGI834 Keywords: Container ship, Design innovation, Suez Canal Copyright <tl 1999 by N. Wijnolst, M . -

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

No. 21264 MULTILATERAL International Convention on tonnage measurement of ships, 1969 (with annexes, official translations of the Convention in the Russian and Spanish languages and Final Act of the Conference). Concluded at London on 23 June 1969 Authentic texts: English and French. Authentic texts of the Final Act: English, French, Russian and Spanish. Registered by the International Maritime Organization on 28 September 1982. MULTILAT RAL Convention internationale de 1969 sur le jaugeage des navires (avec annexes, traductions officielles de la Convention en russe et en espagnol et Acte final de la Conf rence). Conclue Londres le 23 juin 1969 Textes authentiques : anglais et fran ais. Textes authentiques de l©Acte final: anglais, fran ais, russe et espagnol. Enregistr e par l©Organisation maritime internationale le 28 septembre 1982. Vol. 1291, 1-21264 4_____ United Nations — Treaty Series Nations Unies — Recueil des TVait s 1982 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION © ON TONNAGE MEASURE MENT OF SHIPS, 1969 The Contracting Governments, Desiring to establish uniform principles and rules with respect to the determination of tonnage of ships engaged on international voyages; Considering that this end may best be achieved by the conclusion of a Convention; Have agreed as follows: Article 1. GENERAL OBLIGATION UNDER THE CONVENTION The Contracting Governments undertake to give effect to the provisions of the present Convention and the annexes hereto which shall constitute an integral part of the present Convention. Every reference to the present Convention constitutes at the same time a reference to the annexes. Article 2. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of the present Convention, unless expressly provided otherwise: (1) "Regulations" means the Regulations annexed to the present Convention; (2) "Administration" means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is flying; (3) "International voyage" means a sea voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. -

Potential for Terrorist Nuclear Attack Using Oil Tankers

Order Code RS21997 December 7, 2004 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Port and Maritime Security: Potential for Terrorist Nuclear Attack Using Oil Tankers Jonathan Medalia Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary While much attention has been focused on threats to maritime security posed by cargo container ships, terrorists could also attempt to use oil tankers to stage an attack. If they were able to place an atomic bomb in a tanker and detonate it in a U.S. port, they would cause massive destruction and might halt crude oil shipments worldwide for some time. Detecting a bomb in a tanker would be difficult. Congress may consider various options to address this threat. This report will be updated as needed. Introduction The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, heightened interest in port and maritime security.1 Much of this interest has focused on cargo container ships because of concern that terrorists could use containers to transport weapons into the United States, yet only a small fraction of the millions of cargo containers entering the country each year is inspected. Some observers fear that a container-borne atomic bomb detonated in a U.S. port could wreak economic as well as physical havoc. Robert Bonner, the head of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), has argued that such an attack would lead to a halt to container traffic worldwide for some time, bringing the world economy to its knees. Stephen Flynn, a retired Coast Guard commander and an expert on maritime security at the Council on Foreign Relations, holds a similar view.2 While container ships accounted for 30.5% of vessel calls to U.S. -

International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969

Page 1 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. file://C:\Documents and Settings\M.Ventura\Local Settings\Temp\~hh4CFD.htm 2009-09-22 Page 2 of 47 Lloyd’s Register Rulefinder 2005 – Version 9.4 Tonnage - International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 - Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Articles of the International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships Copyright 2005 Lloyd's Register or International Maritime Organization. All rights reserved. Lloyd's Register, its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as the 'Lloyd's Register Group'. The Lloyd's Register Group assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register Group entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. -

NCITEC National Center for Intermodal Transportation for Economic Competitiveness

National Center for Intermodal Transportation for Economic Competitiveness Final Report 525 The Impact of Modifying the Jones Act on US Coastal Shipping by Asaf Ashar James R. Amdal UNO Department of Planning and Urban Studies NCITEC National Center for Intermodal Transportation for Economic Competitiveness Supported by: 4101 Gourrier Avenue | Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70808 | (225) 767-9131 | www.ltrc.lsu.edu TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/LA.525 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date The Impact of Modifying the Jones Act on US Coastal June 2014 Shipping 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Asaf Ashar, Professor Research, UNOTI LTRC Project Number: 13-8SS James R. Amdal, Sr. Research Associate, UNOTI State Project Number: 30000766 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. University of New Orleans Department of Planning and Urban Studies 11. Contract or Grant No. 368 Milneburg Hall, 2000 Lakeshore Dr. New Orleans, LA 70148 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Louisiana Department of Transportation and Final Report Development July 2012 – December 2013 P.O. Box 94245 Baton Rouge, LA 70804-9245 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Conducted in Cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA), Federal Highway Administration 16. Abstract The study assesses exempt coastal shipping defined as exempted from the US-built stipulation of the Jones Act, operating with functional crews and exempted from Harbor Maintenance Tax (HMT). The study focuses on two research questions: (a) the impact of the US-built exemption on the cost of coastal shipping; and (b) the competitiveness of exempt services. -

SHORT SEA SHIPPING INITIATIVES and the IMPACTS on October 2007 the TEXAS TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM: TECHNICAL Published: December 2007 REPORT 6

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/TX-08/0-5695-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date SHORT SEA SHIPPING INITIATIVES AND THE IMPACTS ON October 2007 THE TEXAS TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM: TECHNICAL Published: December 2007 REPORT 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. C. James Kruse, Juan Carlos Villa, David H. Bierling, Manuel Solari Report 0-5695-1 Terra, Nathan Hutson 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas Transportation Institute The Texas A&M University System 11. Contract or Grant No. College Station, Texas 77843-3135 Project 0-5695 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Technical Report: Research and Technology Implementation Office September 2006-August 2007 P.O. Box 5080 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Austin, Texas 78763-5080 15. Supplementary Notes Project performed in cooperation with the Texas Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Project Title: Short Sea Shipping Initiatives and the Impacts on the Texas Transportation System URL: http://tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-5695-1.pdf 16. Abstract This report examines the potential effects of short sea shipping (SSS) development on the Texas transportation system. The project region includes Texas, Mexico, and Central America. In the international arena, the most likely prospects are for containerized shipments using small container ships. In the domestic arena, the most likely prospects are for coastwise shipments using modified offshore service vessels or articulated tug/barges. Only three Texas ports handle containers consistently (Houston accounts for 95% of the total), and three more handle containers sporadically. -

Exploring the Economics of Using Barges on the Mississippi River to Transport Agricultural Commodities

Exploring the Economics of Using Barges on the Mississippi River to Transport Agricultural Commodities Margaret Budde, Louisiana Tanna Nicely, Tennessee A bit of history: The voyages of Columbus excited Europe, and explorers began searching for routes that would help them reach the riches of Asia without having to sail around the lands of the Americas. Without sea access across Central or South America, explorers began searching for a water route through North America. As governor of Cuba, Hernando DeSoto is credited with discovering the Mississippi River in May 1541 on his travels through the southeastern part of North America what is now the states of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana. When he died of a fever, his men weighted down his body and sunk it in the river. LaSalle claimed all land drained by the Mississippi River for France and named it Louisiana. Over 140 years after DeSoto, the next important explorer was LaSalle, a Frenchman who traveled down the Mississippi River from Canada. Reaching the mouth in 1682, he claimed all of the land drained by the great river for France, naming it Louisiana in honor of King Louis XIV. He left for France with the great news and promised to return soon. Tonti of the Iron Hand, an Italian adventurer, friend of LaSalle and historian for the trek down the Mississippi River, left Canada for a second trip hoping to meet LaSalle along the way. Unfortunately, LaSalle misjudged the location of the mouth of the river from the Gulf of Mexico. -

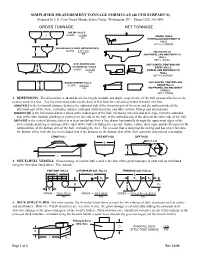

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S

SIMPLIFIED MEASUREMENT TONNAGE FORMULAS (46 CFR SUBPART E) Prepared by U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, Washington, DC Phone (202) 366-6441 GROSS TONNAGE NET TONNAGE SAILING HULLS D GROSS = 0.5 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = 0.9 GROSS SAILING HULLS (KEEL INCLUDED IN D) D GROSS = 0.375 LBD SAILING HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS SHIP-SHAPED AND SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND CYLINDRICAL HULLS D D BARGE HULLS GROSS = 0.67 LBD (PROPELLING MACHINERY IN 100 HULL) NET = 0.8 GROSS BARGE-SHAPED HULLS SHIP-SHAPED, PONTOON AND D GROSS = 0.84 LBD BARGE HULLS 100 (NO PROPELLING MACHINERY IN HULL) NET = GROSS 1. DIMENSIONS. The dimensions, L, B and D, are the length, breadth and depth, respectively, of the hull measured in feet to the nearest tenth of a foot. See the conversion table on the back of this form for converting inches to tenths of a foot. LENGTH (L) is the horizontal distance between the outboard side of the foremost part of the stem and the outboard side of the aftermost part of the stern, excluding rudders, outboard motor brackets, and other similar fittings and attachments. BREADTH (B) is the horizontal distance taken at the widest part of the hull, excluding rub rails and deck caps, from the outboard side of the skin (outside planking or plating) on one side of the hull, to the outboard side of the skin on the other side of the hull. DEPTH (D) is the vertical distance taken at or near amidships from a line drawn horizontally through the uppermost edges of the skin (outside planking or plating) at the sides of the hull (excluding the cap rail, trunks, cabins, deck caps, and deckhouses) to the outboard face of the bottom skin of the hull, excluding the keel. -

13 Ship-Breaking.Com

Information bulletin on September 26th, 2008 ship demolition #13 June 7th to September 21st 2008 Ship-breaking.com February 2003. Lightboat, Le Havre. February 2008 © Robin des Bois From June 7th to September 21st 2008, 118 vessels have left to be demolished. The cumulative total of the demolitions will permit the recycling of more than 940,000 tons of metals. The 2008 flow of discarded vessels has not slowed down. Since the beginning of the year 276 vessels have been sent to be scrapped which represents more than 2 millions tons of metals whereas throughout 2007 289 vessels were scrapped for a total of 1.7 milion tons of metals. The average price offered by Bangladeshi and Indian ship breakers has risen to 750-800 $ per ton. The ship owners are taking advantage of these record prices by sending their old vessels to be demolished. Even the Chinese ship breaking yards have increased their price via the purchase of the container ship Provider at 570$ per ton, with prices averaging more than 500 $. However, these high prices have now decreased with the collapse of metal prices during summer and the shipyards are therefore renegotiating at lower price levels with brokers and cash buyers sometimes changing the final destination at the last minute. This was the case of the Laieta, which was supposed to leave for India for 910 $ per ton and was sold to Bangladesh at 750 $ per ton. The price differences have been particularly notable in India; the shipyards prices have returned to 600 $ per ton. From June to September, India with 60 vessels (51%) to demolish, is ahead of Bangladesh with 40 (34%), The United States 8 (7%), China 4 (4%), Turkey 2 (2%), Belgium and Mexico, 1 vessel each (1%). -

Appendix: Case Studies of Environmental Dredging Projects Table 1

1. Introduction This section describes the sources of available data on which much of the performance standards is based. Completed dredging projects that provide information on upstream and downstream water column conditions, as well as on mass of contaminant removed, provide a basis for determining historical rates of loss and dredging-related recontamination. It was thought that dredging projects that have been completed or are currently in progress can provide practical information on resuspension issues. Information on water quality data, equipment used, monitoring techniques, etc. from these projects will give insight as how to develop the performance standards. For the resuspension standard, water column monitoring results available from other sites were used to complete an analysis of the case study data. The process used to gather relevant information from dredging sites and the information obtained are included herein. It is also important to review all information that exists for the Hudson River. Available data was used to assess the existing variability in the Hudson River water quality, and can be used to estimate the water column quality during and resulting from the dredging operation. Descriptions of the data sets available to perform this analysis are provided herein. 2. Case Studies Objective and Overview During completion of the Hudson River Feasibility Study (FS) and the associated Responsiveness Summary (RS), the GE dredging database, the USEPA website, and other online sources were investigated to identify dredging projects that were relevant and similar to that proposed for the Hudson River in size and complexity. The USEPA and State agencies were contacted to gather information for each dredging project.