Diabetic Foot Ulcer Severity Predicts Mortality Among Veterans with Type 2 Diabetes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Footprints an Informational Newsletter for Patients of APMA Member Podiatrists October 2017

footprints an informational newsletter for patients of APMA member podiatrists october 2017 special EDITION include a DPM for diabetes prevention & Manage Ment According to the CDC, more than 100 million US adults are living with either diabetes or prediabetes. If you have diabetes or prediabetes, it is essential to include a podiatrist for proper diabetes prevention and management. In fact, podiatrists can reduce amputation rates up to 80 percent. In order for you not to become a part of that statistic, here are a few simple things you can do to keep your risk for diabetic ulcers and amputation low: Inspect feet daily. Check your Don’t go barefoot. Don’t go 1 feet and toes every day for 5 without shoes, even in your cuts, bruises, sores, or changes to own home. The risk of cuts and the toenails, such as thickening or infection is too great for those discoloration. with diabetes. Wear thick, soft socks. Avoid Never try to remove calluses, 2 socks with seams, which could 6 corns, or warts by yourself. rub and cause blisters or other Over-the-counter products can burn skin injuries. the skin and cause irreparable damage to the foot for people Exercise. Walking can keep with diabetes. 3 weight down and improve circulation. Be sure to wear See a podiatrist. Regular appropriate athletic shoes when 7 checkups by a podiatrist— exercising. at least annually—are the best WALKING CAN KEEP way to ensure that your feet WEIGHT DOWN AND Have new shoes properly remain healthy. 4 measured and fitted. Foot size IMPROVE CIRCULATION. -

Diabetic Foot Ulcers

REVIEW Review Diabetic foot ulcers William J Jeffcoate, Keith G Harding Ulceration of the foot in diabetes is common and disabling and frequently leads to amputation of the leg. Mortality is high and healed ulcers often recur. The pathogenesis of foot ulceration is complex, clinical presentation variable, and management requires early expert assessment. Interventions should be directed at infection, peripheral ischaemia, and abnormal pressure loading caused by peripheral neuropathy and limited joint mobility. Despite treatment, ulcers readily become chronic wounds. Diabetic foot ulcers have been neglected in health-care research and planning, and clinical practice is based more on opinion than scientific fact. Furthermore, the pathological processes are poorly understood and poorly taught and communication between the many specialties involved is disjointed and insensitive to the needs of patients. In this review, we describe the epidemiology, pathogenesis, operations above the ankle or those proximal to the and management of diabetic foot ulceration, and its effect tarsometatarsal joint, and a multinational WHO survey on on patients and society. The condition deserves more lower extremity amputation also included cases of attention, both from those who provide care and those who unoperated gangrene.13 fund research. Moreover, amputation is a marker not just of disease but also of disease management. The decision to operate Epidemiology is determined by many factors, which vary between Incidence and prevalence centres and patients. A high amputation rate might result Although accurate figures are difficult to obtain for the from high disease prevalence, late presentation, and prevalence or incidence of foot ulcers, the results of cross- inadequate resources, but could also reflect a particular sectional community surveys in the UK showed that 5·3% approach by local surgeons. -

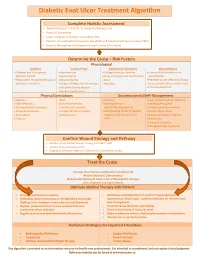

Diabetic Foot Ulcer Treatment Algorithm

Diabetic Foot Ulcer Treatment Algorithm Complete Holistic Assessment Medical/Surgical History & Co-morbidity Management Physical Examination Lower Leg (LLA) including monofilament test Perform Arterial Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) and Toe Brachial Pressure Index (TBPI) Diabetic Management (Glycemic and Lipid Control & Nutrition) Determine the Cause – Risk Factors Physiological Diabetes Vascular Flow Autoimmune Disorders Wound History Diabetes and sub-optimal Hypertension Collagen vascular diseases History of foot infections or glycemic control Heart disease Immunosuppressant medications osteomyelitis Neuropathic changes with lack of Hyperlipidemia Gout Presence of toe infections (fungal protective sensation History of deep vein thrombosis Vasculitis or bacterial), callous and/or corns Peripheral artery disease Previous ulceration Venous Insufficiency Physical Limitations Socioeconomic/Self-Management Obesity Gait Smoking Lack of awareness for self-care Foot deformity Nutritional deficits Inadequate foot Inadequate hygiene Decreased level of activity Limited joint mobility wear/offloading devices Unsafe home environment Visual disturbances Congenital abnormalities Lack/Inability to afford diabetic Alcohol/drug abuse Amputation Osteoporosis supplies, foot care and foot Decreased Cognitive Ability Trauma wear Depression Financial insecurity Decreased level of activity Confirm Wound Etiology and Pathway Results of LLA, Monofilament Testing and ABPI/ TBPI Results of wound assessment Diagnostic -

Associations Between Nutrients and Foot Ulceration in Diabetes: a Systematic Review

nutrients Review Associations between Nutrients and Foot Ulceration in Diabetes: A Systematic Review Nada Bechara 1,2,3, Jenny E. Gunton 2,3,4,* , Victoria Flood 5,6 , Tien-Ming Hng 1 and Clare McGloin 1 1 Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Blacktown-Mt Druitt Hospital, Blacktown, NSW 2148, Australia; [email protected] (N.B.); [email protected] (T.-M.H.); [email protected] (C.M.) 2 Westmead Hospital, Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia 3 Centre for Diabetes, Obesity and Endocrinology Research (CDOER), The Westmead Institute for Medical Research, The University of Sydney, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia 4 Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Darlinghurst, NSW 2010, Australia 5 Westmead Hospital, Research and Education Network, Western Sydney Local Health District, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia; [email protected] 6 Faculty of Medicine and Health, Sydney School of Health Sciences, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We reviewed the literature to evaluate potential associations between vitamins, nutrients, nutritional status or nutritional interventions and presence or healing of foot ulceration in diabetes. Embase, Medline, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library were searched for studies published prior to September 2020. We assessed eligible studies for the association between nutritional status or interventions and foot ulcers. Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this Citation: Bechara, N.; Gunton, J.E.; review. Overall, there is a correlation between poor nutritional status and the presence of foot Flood, V.; Hng, T.-M.; McGloin, C. -

Data Entry II Training Course: Supervisor

Training Data Entry II Training Course: Supervisor PCC Supervisor/Manager PCC Operation Guidelines Rating for one Operator Annual Production Rating Formula Fair 20,000 visits 85 forms per day x 230 days per year Good 40,000 visits 170 forms per day x 230 days per year Outstanding 60,000 visits 260 forms per day x 230 days per year 2 PCC Data Entry Needs and Qualifications • On-Reference Material including: • English & Medical Dictionaries • Medical Abbreviations Book • Up-to-date ICD Coding Books • Drug Handbook-Nursing • Data Entry of 20,000 Forms per year by Trained Individual (about 80 forms per day using six to eight mnemonics). • Number of forms processed or data items entered dependent upon each Area or Site. 3 PCC Data Entry Needs and Qualifications (cont.) • Data Entry Staff with the following skills: • Computer keyboard skills • Ability to read provider’s handwriting • Knowledge and understanding of Medical Terminology • Knowledge and understanding of ICD Coding • Knowledge and understanding of Anatomy and Physiology 4 The International Classification of Diseases • ICD-9-CM: 9th Revision, Clinical Modification • The RPMS Coding System for Diagnoses and Procedures 5 ICD Lookup Process • Enter Provider Narrative • FQ Used File • Synonym File • Key Word File • Possible Code(s) 6 Diabetes Diagnosis Codes 250.00 - 250.93 • Type 1 Diabetes - Insulin Dependent Diabetes (Fairly Rare) • Use the Following fifth digit: • 1 - Indicates controlled • 3 - Indicates uncontrolled Note: Requires insulin to survive 7 Diabetes Diagnosis Codes 250.00 - 250.93 (cont.) • Type 2 Diabetes - Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetes (Most frequent Type) • Use the Following fifth-digit: • 0 - Indicates controlled • 2- Indicates uncontrolled Note: Not dependent on insulin to survive; can produce sufficient amounts but may receive insulin to assist the body in using the insulin present in the body. -

Dosing Pattern of Insulin in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Patients TPI 2019; 8(6): 1196-1199 © 2019 TPI B Sarah Fazeeha, P Nivetha, Albin Eldhose, Dr

The Pharma Innovation Journal 2019; 8(6): 1196-1199 ISSN (E): 2277- 7695 ISSN (P): 2349-8242 NAAS Rating: 5.03 Dosing pattern of insulin in diabetic foot ulcer patients TPI 2019; 8(6): 1196-1199 © 2019 TPI www.thepharmajournal.com B Sarah Fazeeha, P Nivetha, Albin Eldhose, Dr. G Veeramani and Dr. J Received: 04-04-2019 Accepted: 06-05-2019 Kabalimurthy B Sarah Fazeeha Abstract Department of Pharmacy, Background: Among the Diabetic patients, 15% develop a foot ulcer and 12-24% of patients with Annamalai University, Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, diabetic foot ulcer require amputation. We compared the effectiveness of various dosing pattern of India insulin statistically and planned to observe wound healing by proper glycemic control. Methods: We compared the effectiveness of sliding and fixed scale dosing pattern of insulin and P Nivetha observed the wound healing by proper glycemic control. Total 50 subjects were recruited with Grade 3, 4 Department of Pharmacy, and 5 Diabetic foot ulcer (Wagner’s classification) between 40 and 70 years of age who underwent Annamalai University, surgery for management of Foot ulcer. The study was conducted in Tertiary care teaching hospital in Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, Chidambaram. The study period was 6 month and it was a prospective observational study. The blood India glucose level (Fasting, Random and Post prandial) of subjects were monitored on daily basis and observed. Albin Eldhose Results: The study reports suggested that the major risk factors for Diabetic Foot Ulcer were Poor Department of Pharmacy, glycemic control, Male gender, left foot, Ulcer of size more than 2cm, Infection. -

Diabetic Neuropathy: a Position Statement by the American

136 Diabetes Care Volume 40, January 2017 Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Rodica Pop-Busui,1 Andrew J.M. Boulton,2 Eva L. Feldman,3 Vera Bril,4 Roy Freeman,5 Statement by the American Rayaz A. Malik,6 Jay M. Sosenko,7 and Dan Ziegler8 Diabetes Association Diabetes Care 2017;40:136–154 | DOI: 10.2337/dc16-2042 Diabetic neuropathies are the most prevalent chronic complications of diabetes. This heterogeneous group of conditions affects different parts of the nervous system and presents with diverse clinical manifestations. The early recognition and appropriate man- agement of neuropathy in the patient with diabetes is important for a number of reasons: 1. Diabetic neuropathy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Nondiabetic neuropathies may be present in patients with diabetes and may be treatable by specific measures. 2. A number of treatment options exist for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy. 3. Up to 50% of diabetic peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic. If not recognized and if preventive foot care is not implemented, patients are at risk for injuries to their insensate feet. 4. Recognition and treatment of autonomic neuropathy may improve symptoms, POSITION STATEMENT reduce sequelae, and improve quality of life. Among the various forms of diabetic neuropathy, distal symmetric polyneurop- athy (DSPN) and diabetic autonomic neuropathies, particularly cardiovascular au- tonomic neuropathy (CAN), are by far the most studied (1–4). There are several 1 atypical forms of diabetic neuropathy as well (1–4). Patients with prediabetes may Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabe- – tes, Department of Internal Medicine, University also develop neuropathies that are similar to diabetic neuropathies (5 10). -

11. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care: Standards of Medical

Diabetes Care Volume 43, Supplement 1, January 2020 S135 11. Microvascular Complications American Diabetes Association and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes22020 Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl. 1):S135–S151 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-s011 11. MICROVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS AND FOOT CARE The American Diabetes Association (ADA) “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” includes the ADA’s current clinical practice recommendations and is intended to provide the components of diabetes care, general treatment goals and guidelines, and tools to evaluate quality of care. Members of the ADA Professional Practice Committee, a multidisciplinary expert committee (https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20- SPPC), are responsible for updating the Standards of Care annually, or more frequently as warranted. For a detailed description of ADA standards, statements, and reports, as well as the evidence-grading system for ADA’s clinical practice recommendations, please refer to the Standards of Care Introduction (https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-SINT). Readers who wish to comment on the Standards of Care are invited to do so at professional.diabetes.org/SOC. For prevention and management of diabetes complications in children and adoles- cents, please refer to Section 13 “Children and Adolescents” (https://doi.org/10.2337/ dc20-S013). CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE Screening Recommendations 11.1 At least once a year, assess urinary albumin (e.g., spot urinary albumin-to- creatinine ratio) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in patients with type 1 diabetes with duration of $5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes regardless of treatment. B Patients with urinary albumin .30 mg/g creatinine and/or an eGFR ,60 mL/min/1.73 m2 should be monitored twice annually to guide therapy. -

Diabetic Foot Infections Download

ARTICLE DIABETIC FOOT INFECTIONS OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES IN CLINICAL RESEARCH Diabetic foot infections (DFI) are a frequent and complex secondary complication of diabetes that inflict a substantial financial burden on society and are associated with the potential for serious health consequences. The prevalence of DFI is significant, considering that more than 382 million people are living with diabetes worldwide, of which 25% will experience at least one diabetic foot ulcer and approximately 58% of these are likely to become clinically infected.1,2 As such, diabetic foot complications continue to be responsible for the majority of diabetes-related hospitalizations and lower extremity amputations as well as pose a serious risk for death related to infection. Unfortunately, guidelines regarding the diagnosis and treatment of DFI are not specific.1 Additionally, there is a lack of uniformity in clinical trials involving DFI. Differences in design, terminology, and clinical and microbiological outcome measurements pose significant challenges to comparing results among randomized controlled trials (RCT).3 Thus, research in diagnosis, management, and therapy development, as well as development of standardized guidelines for upcoming studies need to be addressed in order to improve the prognosis of DFI patients. AN AT-RISK POPULATION Infection by invading pathogenic organisms is of particular concern for the diabetic population. Diabetes mellitus, a metabolic condition characterized by prolonged elevated blood sugar as a result of inadequate and/or defective insulin production, triggers many downstream metabolic pathways leading to inflammation, nerve damage, circulatory dysfunction, impaired signaling and an altered immune system. The multifactorial nature of diabetes results in diminished wound healing that predisposes diabetics to foot ulcers with the potential for infection. -

Diabetic Ulcer Identification & Treatment

Diabetic Ulcer Identification & Treatment Bill Richlen PT, WCC, DWC, Clinical Instructor Wound Care Education Institute The information in this handout reflects the state of knowledge, current at time of publication; however, the authors do not take responsibility for data, information, and significant findings related to the topics discussed that became known to the general public following publication. The recommendations contained herein may not be appropriate for use in all circumstances. Decisions to adopt any particular recommendation must be made by the practitioner in light of available resources and circumstances presented by individual patients. Acknowledgements: This handout and presentation was prepared using information generally acknowledged to be consistent with current industry standards. The authors whose works are cited in the Bibliography Section of this manual are hereby recognized and appreciated. All product names, logos and trademarks used in this presentation are the property of the respective trademark owners. ® and ™ denote registered trademarks in the United States and other countries. "The use of NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA material does not imply endorsement of products or programs associated with the use of the material." Wound Care Education Institute (WCEI) Phone: 877-462-9234 Email: [email protected] www.wcei.net Copyright © 2018 by Wound Care Education Institute All Rights Reserved. WCEI grants permission for photocopying for limited personal or educational use only. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying, such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale. Treating Chronic Diabetic Wounds Outline I. Chronic Wounds A. Some Details 1. Definition: A wound that has failed to proceed orderly through the healing process or fails to result in durable closure.3 a. -

Drug-Induced Hyperglycemia Risk Factors Presentation Causative Agents Mallory Linck, Pharm.D

9/29/12 Outline Drug-Induced Hyperglycemia Risk Factors Presentation Causative Agents Mallory Linck, Pharm.D. Mechanisms Pharmacy Practice Resident Prevention University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Management Risk Factors Presentation of Drug-Induced Hyperglycemia Mild-to-Moderate Severe disease General Diabetes risk factors, plus: Blurred vision Abdominal Pain, N/V Pre-existing or underlying Diabetes Excessive thirst Coma Higher doses of thiazides or corticosteroids Fatigue/weakness Dehydration Use of more than one drug that can induce Polydipsia Hypokalemia hyperglycemia Polyphagia Hypotension Polypharmacy Polyuria Kussmaul respiration and Unexplained weight loss fruity breath Increased Blood Glucose Lethargy Metabolic acidosis Causative Agents Mechanisms Atypical antipsychotics Nicotinic acid B-blockers Oral contraceptives Cyclosporine Pentamidine Diazoxide Phenothiazines Thiazide Diuretics Phenytoin Fish oil Protease inhibitors Glucocorticoids Rifampin Growth Hormone Ritodrine Interferons Tacrolimus Megesterol Terbutaline Thalidomide 1 9/29/12 Thiazide Diuretics High doses Hypokalemia “Each 0.5mEq/L decrease in serum potassium was associated with a 45% higher risk of new diabetes” DECREASE INSULIN SECRETION Plan: Use smaller doses (12.5-25mg/day HCTZ) and replace potassium Shafi T. Hypertension. 2009 Feb;53(2):e19. Immunosuppressants Overall incidence 4-46% Pre-disposing factors Genetics Metabolic syndrome Increasing age Most common in the first few months post- transplant -

Clinician Assessment Tools for Patients with Diabetic Foot Disease: a Systematic Review

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Clinician Assessment Tools for Patients with Diabetic Foot Disease: A Systematic Review Raúl Fernández-Torres 1 , María Ruiz-Muñoz 1,* , Alberto J. Pérez-Panero 1 , Jerónimo C. García-Romero 2 and Manuel Gónzalez-Sánchez 3 1 Department of Nursing and Podiatry, University of Málaga, Arquitecto Francisco Peñalosa, s/n. Ampliación Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Málaga, Spain; [email protected] (R.F.-T.); [email protected] (A.J.P.-P.) 2 Medical School of Physical Education and Sports, University of Málaga, C/Jiménez Fraud 10. Edificio López de Peñalver, 29010 Málaga, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Physiotherapy, University of Málaga, Arquitecto Francisco Peñalosa, s/n. Ampliación campus de Teatinos, 29071 Málaga, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-951953215 Received: 10 April 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020; Published: 15 May 2020 Abstract: The amputation rate in patients with diabetes is 15 to 40 times higher than in patients without diabetes. To avoid major complications, the identification of high-risk in patients with diabetes through early assessment highlights as a crucial action. Clinician assessment tools are scales in which clinical examiners are specifically trained to make a correct judgment based on patient outcomes that helps to identify at-risk patients and monitor the intervention. The aim of this study is to carry out a systematic review of valid and reliable Clinician assessment tools for measuring diabetic foot disease-related variables and analysing their psychometric properties. The databases used were PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, CINAHL, Cochrane, PEDro, and EMBASE. The search terms used were foot, ankle, diabetes, diabetic foot, assessment, tools, instruments, score, scale, validity, and reliability.