Colleen Zither Repair Log.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solo and Ensemble Concert Mae Zenke Orvis Auditorium July 17, 1967 8:00 P.M

SOLO AND ENSEMBLE CONCERT MAE ZENKE ORVIS AUDITORIUM JULY 17, 1967 8:00 P.M. SOLO AND ENSEMBLE CONCERT Monday, July 17 Mae Zenke Orvis Auditorium 8:00 P.M. Program Ernst Krenek Piano Sonata No.3 (1943) Peter Coraggio, piano Allegretto piacevole Theme, Canons and Variations: Andantino Scherzo: Vivace rna non troppo Adagio First Performance in Hawaii Neil McKay Sonata for French Horn and Willard Culley, French horn Piano (1962) Marion McKay, piano Fanfare: Allegro Andante Allegro First Performance in Hawaii Chou Wen-chung Yu Ko (1965) Chou Wen-chung, conductor First Performance in Hawaii John Merrill, violin Jean Harling, alto flute James Ostryniec, English horn Henry Miyamura, bass clarinet Roy Miyahira, trombone Samuel Aranio, bass trombone Zoe Merrill, piano Lois Russell, percussion Edward Asmus, percussion INTERMISSION JOSe Maceda Kubing (1966) Jose Maceda, conductor Music for Bamboo Percussion and Men's Voices First Performance in Hawaii Jose Maceda Kubing (1966) Jose Maceda, conductor Music for Bamboo Percussion Charles Higgins and Men's Voices William Feltz First Performance in Hawaii Brian Roberts voices San Do Alfredo lagaso John Van der Slice l Takefusa Sasamori tubes Bach Mai Huong Ta buzzers ~ Ruth Pfeiffer jaw's harps Earlene Tom Thi Hanh le William Steinohrt Marcia Chang zithers Michael Houser } Auguste Broadmeyer Nancy Waller scrapers Hailuen } Program Notes The Piano Sonata NO.3 was written in 1943. The first movement is patterned after the classical model: expo sition (with first, second, and concluding themes), development, recapitulation, and coda. However, in each of these sections the thematic material is represented in musical configurations derived from one of the four basic forms of the twelve-tone row: original, inversion, retrograde, and retrograde inversion. -

Piano Manufacturing an Art and a Craft

Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Gesa Lücker (Concert pianist and professor of piano, University for Music and Drama, Hannover) Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Since time immemorial, music has accompanied mankind. The earliest instrumentological finds date back 50,000 years. The first known musical instrument with fibers under ten sion serving as strings and a resonator is the stick zither. From this small beginning, a vast array of plucked and struck stringed instruments evolved, eventually resulting in the first stringed keyboard instruments. With the invention of the hammer harpsichord (gravi cembalo col piano e forte, “harpsichord with piano and forte”, i.e. with the capability of dynamic modulation) in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, the pianoforte was born, which over the following centuries evolved into the most versitile and widely disseminated musical instrument of all time. This was possible only in the context of the high level of devel- opment of artistry and craftsmanship worldwide, particu- larly in the German-speaking part of Europe. Since 1885, the Schimmel family has belonged to a circle of German manufacturers preserving the traditional art and craft of piano building, advancing it to ever greater perfection. Today Schimmel ranks first among the resident German piano manufacturers still owned and operated by Contents the original founding family, now in its fourth generation. Schimmel pianos enjoy an excellent reputation worldwide. 09 The Fascination of the Piano This booklet, now in its completely revised and 15 The Evolution of the Piano up dated eighth edition, was first published in 1985 on The Origin of Music and Stringed Instruments the occa sion of the centennial of Wilhelm Schimmel, 18 Early Stringed Instruments – Plucked Wood Pianofortefa brik GmbH. -

Restoration of C. 1925-1930 Carl Fischer Concert Zither

Restoration of C. 1925-1930 Carl Fischer Concert Zither Completed by Ron Cook April 2018 For David Spirk Background Tens of thousands of concert zithers were manufactured in both Europe and the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s. There were many shapes and styles, with the number of strings often ranging from 31 to 46. Most concert zithers were basic “entry level” instruments with little or no decoration and a laminated front (usually black walnut) and sides with a back painted black. Some, like the gorgeous zither in this repair log, were highly ornate and decorated with marquetry, mother of pearl and abalone inlays and laminated walnut or rosewood on the front, sides and back. The label inside this beautiful concert zither is very faded from moisture, but the name Carl Fischer is visible as is the street name, Cooper Square. Carl Fischer Music was founded in 1872 when he opened his musical instrument repair shop in an East Village neighborhood of New York City. He supplied musicians with sheet music, including zither music, and instruments from Europe, while supplementing his income with professional engagements as a violinist in several orchestras and bands throughout the city. As his company grew too large for the original store, his family, in 1924, shortly after Carl passed away, constructed a new 12-story building on Cooper Square, in Manhattan, where they stayed until the fourth-generation heirs sold the building in 1999. The company, now 146 years old, is currently based on Long Island. Carl Fischer was not an instrument manufacturer, but a reseller. -

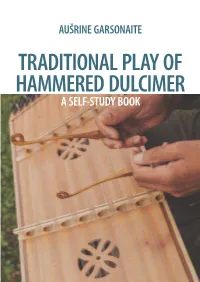

Traditional Play of Hammered Dulcimer a Self-Study Book Traditional Play of Hammered Dulcimer

AUŠRINE GARSONAITE TRADITIONAL PLAY OF HAMMERED DULCIMER A SELF-STUDY BOOK TRADITIONAL PLAY OF HAMMERED DULCIMER Turinys About the book ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 A Brief Overview of the History of Traditional Music: What Has Changed Over Time? .................................................................................................................... 3 The Dulcimer: Then and Now .................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: General Knowledge and Striking Strings in a Row 1.1. Correctly Positioning the Dulcimer and Holding the Hammers; First Sounds ....................................... 10 1.2. Playing on the Left Side of the Treble Bridge 1.2.1. First Compositions in A Major ................................................................................................................. 15 1.2.2. Playing Polka in D ........................................................................................................................................ 17 1.3. Playing on the Right Side of the Treble Bridge 1.3.1. Performing Compositions You Already Know in D Major ............................................................. 20 1.3.2. Performing a Composition You Already Know in G Major ............................................................ 22 1.4. Playing on the Left Side of the Bass Bridge -

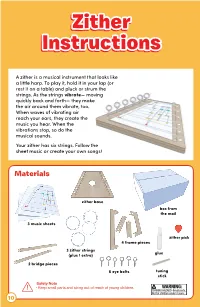

Zither Instructions

ZitherZither Build the Zither Connect the four frame Squeeze glue along the InstructionsInstructions pieces. Clear away any outside edges of the frame, excess debris from the holes. avoiding the holes. A zither is a musical instrument that looks like a little harp. To play it, hold it in your lap (or rest it on a table) and pluck or strum the strings. As the strings vibrate— moving quickly back and forth— they make the air around them vibrate, too. Carefully place the zither base Squeeze glue into the slots When waves of vibrating air on top of the frame. If glue gets near the edges of the zither reach your ears, they create the into any of the holes, wipe it base. Place the bridge pieces music you hear. When the away with a toothpick. Place a into the slots and let them dry vibrations stop, so do the heavy book on the frame and let for 10 minutes. musical sounds. it dry for 30 minutes. Your zither has six strings. Follow the sheet music or create your own songs! Materials Insert eye bolts into the two Starting from the back, zither base bottom-left holes. Twist the thread the ends of one string box from bolts clockwise until they’re through the holes on the the mail halfway into the bottom piece opposite sides of the bolts. 3 music sheets of the frame. Pull the ends until the string lengths are even. zither pick 4 frame pieces 3 zither strings glue (plus 1 extra) 2 bridge pieces 6 eye bolts tuning stick Safety NoteSafety Note WARNING:WARNING: • Keep small• Keep parts small and parts string and out string of reach out of of reach young of children.young children. -

A Set of Performance Practice Instructions for a Western Flautist Presenting Japanese and Indian Inspired Works

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2007 Blowing east : A set of performance practice instructions for a western flautist presenting Japanese and Indian inspired works Asha Henfry Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Music Practice Commons Recommended Citation Henfry, A. (2007). Blowing east : A set of performance practice instructions for a western flautist presenting Japanese and Indian inspired works. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1301 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1301 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Sfkieherd Sc~Ol Ofmusic

BRASS AND ORGAN CONCERT featuring students of The Shepherd School of Music and Phillip Kloeckner, Organist Sunday, March 22, 2009 4:00 p.m. Edythe Bates Old Recital Hall .and Grand Organ I I~ r sfkieherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic I PROGRAM Suite of Dances Andre Campra (1660-1744) trans. Scott Sorenson Kevin Lynch, trumpet Thomas Siders, trumpet Julie Thayer, horn Benjamin Zither, trombone Andrew Welborn, tuba My Spirit be Joyful Johann Sebastian Bach (Wie will ich michfreuen) (1685-1750) from the Easter Cantata No. 146 arr. E. Power Biggs Patrick Corvington, trumpet Brian Hess, trumpet Hodie Christus Natus Est Giovanni Gabrieli (1554-1612) arr. Gary Olson Ryan Darke, trumpet Robert Zider, trumpet Nicholas Hartman, horn Samuel Jackson, trombone Sarah Herald, tuba Sonata a 4 Trombones Daniel Speer from Neu-gebachene Taffel-Schnitz (1865) (1636-1707) ed. Howard Weiner I arr. Tom Godfrey Caitlin Hickey, trombone J1 Samuel Jackson, trombone Travis Sheaffer, trombone John Stanley, bass trombone \ Canzon cornetto a 4 Samuel Scheidt (1587-1654) arr. Wolfgang G. Haas Patrick Corvington, trumpet Brian Hess, trumpet Kevin Lynch, trumpet Thomas Siders, trumpet INTERMISSION Marche Triomphale Sigfrid Karg-Elert (1877-1933) Patrick Corvington, trumpet Brian Hess, trumpet Roman Ponomariov, horn Travis Scheafer, trombone John Stanley, bass trombone PieJesu Andrew Lloyd Webber from Requiem (b. 1948) Kevin Lynch, flugelhorn Thomas Siders, trumpet Psalm 84: Cantique de Jean Racine Gabriel Faure (1845-1924) arr. Tom Godfrey Caitlin Hickey, trombone Travis Sheaffer, trombone Benjamin Zilber, trombone John Stanley, bass trombone Toccata and Fugue Johann Sebastian Bach in D Minor, BWV565 (1685-1750) Phillip Kloeckner, organist Salvum Fae Populam Tuum Charles-Marie Widor (1844-1937) Brian Hess, trumpet Kevin Lynch, trumpet Thomas Siders, trumpet Samuel Jackson, trombone Travis Shaeffer, trombone Benjamin Zilber, trombone Gregory Tsalikis, percussion Marie Speziale, conductor Solemn Entry of the Knights Richard Strauss of the Order of St. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

The Musical Angels of Rosslyn Chapel

The Musical Angels of Rosslyn Chapel Music was an important part of medieval life, both religious and secular. Bands of musicians would play for special feast days such as Christmas or Easter, and for special events such as trade fairs. The nobility encouraged their children to learn a musical instrument, and it was common for noble girls and boys to learn to play a drum or simple wind instrument. In churches and monasteries, the voice was the principal instrument of music, starting in the early middle ages with plainsong such as Gregorian Chant, developing into polyphonous music by the start of the Renaissance. As music became more complex, musical notation was developed. There are some fine examples of medieval sheet music preserved in the special collections department of the University of Edinburgh Library. Rosslyn Chapel, founded in 1446, features many intriguing details carved in stone. In the Lady Chapel, carved at the tops of pillars, there are a number of angels playing musical instruments. These angels represent the Heavenly Hosts, praising God and rejoicing over the birth of Christ. It has long been public knowledge that one of the angels is playing the bagpipes, and that this is one of the earliest depictions of bagpipes in Scotland. However, the identities of many of the other instruments in the chapel are less well known. Young Research Group volunteers Rory Hardie and Hannah Mooney consulted with experts in medieval music, and have identified them as the following: Psaltery The psaltery, or a harp on a box, is an ancient instrument that was played by plucking the strings while the instrument lay in the player’s lap. -

Belgium, Remi Decker, “Bagpipe Heritage in Belgium”

BELGIUM Belgium (Dutch: België; French: Belgique; German: Belgien), is a federal monarchy in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters as well as those of several other major international organizations such as NATO. Belgium covers an area of 30,528 square kilometres (11,787 sq mi), and it has a population of about 11 million people. Straddling the cultural boundary between Germanic and Latin Europe, Belgium is home to two main linguistic groups: the Dutch-speaking, mostly Flemish community (59% of the population), and the French-speaking, mostly Walloon population (41% of all Belgians). Additionally, there is a small group of German-speakers who are officially recognized. Belgium's two largest regions are the Dutch-speaking region of FLANDERS in the north and the French-speaking southern region of WALLONIA. The Brussels-Capital Region is officially bilingual. A German-speaking Community exists in eastern Wallonia. Belgium's linguistic diversity and related political conflicts are reflected in its political history and complex system of government. Historically, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg were known as the Low Countries, which used to cover a somewhat larger area than the current Benelux group of states. "TRADITION" Because of their geographical situation and political history, the Low Countries have always been open to foreign cultural influences. Consequently, they share most of their musical traditions with neighbouring areas in Germany and France. Since the Middle Ages the Low Countries have also been among the most urbanized areas of Europe, which has meant a continuous cultural interaction between social classes. -

A Brief History of the Hammered Dulcimer

Phil Passen Press Kit!page 2 A Brief History of the Hammered Dulcimer The trapezoidal-shaped hammered dulcimer, coming in sizes from 3 to 5 octaves with 40 to 100 strings, is the direct ancestor of the piano. In this country it’s called the hammered dulcimer to distinguish it from the lap, or Appalachian dulcimer (a strummed 4 string instrument originating in the Appalachian mountains in the 1800’s). The two instruments have nothing in common except their names, and that they are both usually classified as members of the zither family. The commonly accepted theory about the the hammered dulcimer’s beginnings is that it originated in Persia; that it was brought into western Europe between 900 and 1200 by the Moors and by returning Crusaders; and that it was brought into eastern Europe by the Roma people. But in his well researched and documented book, The Hammered Dulcimer, Paul Gifford presents an alternative opinion, arguing that the dulcimer developed independently in Europe in the early fifteenth century and was related to the European psaltery, a plucked instrument which in turn may have been related to the Mideastern psaltery. Whatever its origins, by 1600 the dulcimer was firmly established in Europe and was popular in the court of King James I of England. In the Book of Daniel in the King James version of the Bible, Nebuchadnezzar’s band was said to contain a dulcimer, leading people to assume that the dulcimer existed in biblical times. Subsequent research has shown that the Hebrew word translated as dulcimer actually meant something else — bagpipe or string drum or perhaps flute. -

Aesthetic and Spiritual Correlations in Javanese Gamelan Music

SUSAN PRATT WALTON Aesthetic and Spiritual Correlations in Javanese Gamelan Music There are striking similarities and intriguing con- in part, to support, manifest, and express that sys- nections between the tradition of gamelan music tem. The stated aim of music making, the structure in Java and Javanese mystical traditions. A game- of the music, the leadership styles, and the creation lan is an ensemble of gongs, metalophones, drums, of melodies have remarkably close parallels in the bowed lute, xylophone, zither, bamboo flute, and Javanese mystical world.2 singers. Gamelans of many different types exist in My analysis of the link between Javanese mu- Java, Bali, and Lombok, as well as in Malaysia. sical and mystical traditions centers on the con- Some include only a few gongs; others have up cept of rasa, which is crucial to both traditions. to fifty instruments. The type of ensemble that I start with the ancient Sanskrit theory of rasa, concerns us is the largest of these ensembles, the then move to the central role of rasa in contempo- gamelan of Central Java. Its most important func- rary Java musical groups, followed by an analysis tion is to accompany dance, theater, and ceremo- of Sumarsam’s “inner melody” theory of Javanese nial occasions, such as weddings, in both ritual and music. Finally, I show that rasa is not merely an commercial settings. abstract construct accessible to an elite cadre of The links between the musical and mystical tra- the most knowledgeable gamelan musicians: it is ditions of Java have not been much noticed or ex- the basis of music making for many musicians, es- amined in the scholarly literature.