The Parthenon's North Colonnade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25, 1975, Number 3 LP-0899 THE ARCH AND COLONNAD E OF THE MANHATTAN BRIDGE APPROACH, Manhattan Bridge Plaza at Canal Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1912-15; architects Carr~re & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough o£Manhattan Tax Map Block 290, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described improvement is situated. On September 23, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No . 3). The hearing had been duly ad vertised in accordance with . the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Manhattan Bridge Approach, a monumental gateway to the bridge, occupies a gently sloping elliptical plaza bounded by Canal, Forsyth and Bayard Streets and the Bowery. Originally designed to accommodate the flow of traffic, it employed traditional forms of arch and colonnade in a monument al Beaux-Arts style gateway. The triumphal arch was modeled after the 17th-century Porte St. Denis in Paris and the colonnade was inspired by Bernini's monumental colonnade enframing St. Peter's Square in Rome. Carr~re &Hastings, whose designs for monumental civic architecture include the New York Public Library and Grand Army Plaza, in Manhattan, were the architects of the approaches to the Manhattan Bridge and designed both its Brooklyn and Manhattan approaches. The design of the Manhattan Bridge , the the third bridge to cross the East River, aroused a good deal of controversy. -

Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, Was Designed and Constructed Under the U

FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Youngstown, Ohio Youngstown, Ohio The Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, was designed and constructed under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve a legacy of outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. Special thanks to the Honorable William T. Bodoh, Chief Bankruptcy Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for his commitment and dedication to a building of outstanding quality that is a tribute to the role of the judiciary in our democratic society and worthy U.S. General Services Administration U.S. General Services Administration of the American people. Public Buildings Service Office of the Chief Architect Center for Design Excellence and the Arts October 2002 1800 F Street, NW Washington, DC 20405 2025011888 FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Youngstown, Ohio Youngstown, Ohio The Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, was designed and constructed under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve a legacy of outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. Special thanks to the Honorable William T. Bodoh, Chief Bankruptcy Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for his commitment and dedication to a building of outstanding quality that is a tribute to the role of the judiciary in our democratic society and worthy U.S. -

COLONNADE RENOVATION Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia

CSI Richmond – April Project Spotlight - Glavé & Holmes Architecture COLONNADE RENOVATION Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia Washington and Lee University’s front campus was designated a National Historic District in 1973, described by the Interior as “one of the most dignified and beautiful college campuses in the nation”. In the center stands the Colonnade, comprised of the five most iconic buildings in the historic district: Washington, Payne, Robinson, Newcomb, and Tucker Halls. The phased rehabilitation of the building spanned eight years. The Colonnade is deeply revered, making any change sensitive. However, restoring its vitality was paramount to the University: code deficiencies, inefficient infrastructure, and worn interiors reflected decades of use. Offices were inadequate, spaces for interaction were sparse, technology was an afterthought, and there weren’t even bathrooms on the third floors. Understanding the beloved nature of the buildings, the University established lofty goals for this undertaking. G&HA followed the guidelines from the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation to preserve the major character and defining features in each building while upgrading all the MEP and life safety systems throughout. Because of space constraints, a new utility structure was designed and located across Stemmons Plaza to sit below grade. The structure’s green roof and seating areas integrate it into the site and enhance the landscape. The project achieved LEED Silver and historic tax credits. — COLONNADE -

Test Trench in the Street of the Great Colonnade

PALMYRA SYRIA TEST TRENCH IN THE STREET OF THE GREAT COLONNADE Marta ¯uchowska In connection with work in the western The tracing of the street was un- sector of the ruins of ancient Palmyra, a test doubtedly an important urban project. trench was dug in the 2001 and 2002 Not only were preexisting structures seasons in the street of the Great Colon- removed, but also an extensive water nade.1) The trench, which was 3.50 m wide supply and sewage system was put into and 14 m long, cut through the street in one place. Under level I of the street two fresh- of the intercolumnia. A small section of the water pipes were laid (cf. Fig. 2: pipes 2, 6) south portico was cleaned down to the beside a sewer made of small stones with Roman level. The chief objective was to a carved stone trough and a large lime- study the stratigraphy and to verify earlier stone-slab covering (cf. Fig. 2: sewer). ideas about the dating of successive phases The first street surface (level I) was of the main street of the town. In the course made of heterogeneous stone gravel and of two seasons of excavations, a number of clay. It did not survive long as two more layers corresponding to the phases of street water pipes had to be laid soon afterwards development came to light along with (cf. Fig. 2: pipes 3, 4). The new surface of substantial evidence of hydraulic instal- the street corresponded to a time of growth lations constituting part of the ancient and prosperity in this part of the town. -

First Impression : the Study of Entry in Architecture

Copyright Warning & Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a, user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use” that user may be liable for copyright infringement, This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. Please Note: The author retains the copyright while the New Jersey Institute of Technology reserves the right to distribute this thesis or dissertation Printing note: If you do not wish to print this page, then select “Pages from: first page # to: last page #” on the print dialog screen The Van Houten library has removed some of the personal information and all signatures from the approval page and biographical sketches of theses and dissertations in order to protect the identity of NJIT graduates and faculty. FIRST IMPRESSION: THE STUDY OF ENTRY IN ARCHITECTURE by Siriwan Polpuech Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the New Jersey Institute of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Architectural Studies 1989 APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: First Impression: The Study of Entry in Architecture Name of Candidate: Siriwan Polpuech Master of Science in Architectural Studies, 1989 Thesis and Abstract Approved: Prof. -

The Internal Colonnade of the Hephaisteion

THE INTERNAL COLONNADE OF THE HEPHAISTEION (PLATE 56) T HE unexpected discovery, in 1939, of the foundations of an internal colonnade within the Hephaisteion,' contrasting with the general practice of its designer, the " Theseum architect," and the accumulatilonof evidence that both the foundations and the colonnade were, in fact, not parts of the original scheme but were inserted (undoubtedly by the original architect himself) as an afterthought and the entire cella building redesigned in emulation of the new contemporary design for the Par- thenon may now be accepted as a definite acquisition.2 Far otherwise is it with regard to the details of the restoration, for which, apart from the very incomplete grave-riddled foundations themselves, there are only two items of internal evidence, a single marble block from the epistyle over the upper tier of columns (with a very peculiar jogged joint suggesting that it came from an end or a corner), together with a single vertical scratch line at the floor level on the north flank wall. One more extant block, or even one more scratch line, might have eliminated all the speculation to which we are condemned. On the basis of this slender evidence two main types of restoration, A with two by five column intervals and B with three by seven intervals, with minor differ- ences yielding five sub-varieties, as well as two others that have been mentioned only to be immediately discarded, have been successively published: Al, the extant epistyle placed at the southeast corner (Dinsmoor, 1941); 3 A2, again at the southeast corner 'This article was written in 1953, and immediately submitted to Bert Hodge Hill for criticism. -

Art Concepts

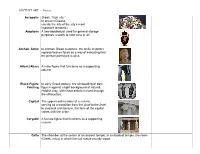

ANCIENT ART - Greece Acropolis Greek, “high city.” In ancient Greece, usually the site of the city’s most important temple(s). Amphora A two-handled jar used for general storage purposes, usually to hold wine or oil. Archaic Smile In Archaic Greek sculpture, the smile sculptors represented on faces as a way of indicating that the person portrayed is alive. Atlant (Atlas) A male figure that functions as a supporting column. Black-Figure In early Greek pottery, the silhouetting of dark Painting figures against a light background of natural, reddish clay, with linear details incised through the silhouettes. Capital The uppermost member of a column, serving as a transition from the shaft to the lintel. In classical architecture, the form of the capital varies with the order. Caryatid A female figure that functions as a supporting column. Cella The chamber at the center of an ancient temple; in a classical temple, the room (Greek, naos) in which the cult statue usually stood. ANCIENT ART - Greece Centaur In ancient Greek mythology, a fantastical creature, with the front or top half of a human and the back or bottom half of a horse. Contrapposto The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counterpositioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called “weight shift” because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other. Corinthian Corinthian columns are the latest of the three Greek styles and show the influence of Egyptian columns in their capitals, which are shaped like inverted bells. -

Imagine Create

Create All products are available in these standard colors: Imagine WHITE IVORY GRANITE SANDSTONE MILLSTONE BLACKSTONE TERRA COTTA “ is a lot like looking at the world through a kaleidoscope. CreativityYou look at a set of elements, the same ones everyone else sees, but then reassemble those floating bits and pieces into an enticing new possibility.” DR. - ROSABETH MOSS KANTER Wedding Group Balustrade Group 534 Balustrade Pedestal Capital 16” sq. 548 530 Balustrade, with 4 balusters Balustrade Pedestal 30”h 14” sq. 549 Balustrade Corner 14” sq. Above wedding set up includes: • Column Arch System consisting of (4) 600 Columns, (4) 648 Quarter Circle Tops/Bases, (1) 618 Arch • (2) 349 Wicker Look Flower Baskets DISPLAY BELOW: • (2) 327 Garden Urns The display below includes: • (3) 530 Balustrade Pedestal • (3) 534 Balustrade Pedestal Capital • (1) 549 Balustrade Corner • (2) 548 Balustrade with 4 balusters • (2) 522 Classic Square Base Urn (shown on page 8) 618 Colonnade Arch 640 72”w x 18” h 600 Scamozzi Pedestal 696 Scamozzi Capital 40” Scamozzi Capital Column 72” Column 96” COVER PHOTO: Tuscan Oval Colonade on front cover includes: • (6) 660 Columns • (4) 648 Quarter Circles • (1) 672 Straight 648 • (1) 620 “New” Soft-Curved Arch Colonnade Top or Base, Quarter Circle 8’ • (4) Oval Colonade Bases - 2 left, 2 right Also available: 672 • (6) 220 ”New” Multi-Purpose Light Bases Straight Colonnade Top or Base 8’ • (6) 661 “New” Column Caps for 660 2 3 Classic Series Pedestals, Columns & Caps Empire Series 406 Round Pedestal Capital 6” 206 Classic Square Pedestal Capital 4” 402 Round Base 403 20” Pedestal 404 Round Base Round Base 30” Pedestal 204 Square Base Pedestal 40” Pedestal illuminated by 200 Square Light Base 207 Classic Iconic Pedestal Capital 5” 802 Empire Display Cap 800 Trojan Column 96” SPECIAL NOTES: 202 All dimensions are approximate. -

Decorate a Colonnade Arch System

HOW TO Decorate a Colonnade Arch System Decorating a colonnade arch system that can serve as the focal point of a wedding ceremony demands far more artistry than most wedding guests understand. It needs to focus attention on the bride and groom and draw attention away from the venue without attracting too much attention to itself. It provides the backdrop for the memories, wedding photos and videos that will live on for generations. And there’s only one chance for success. That’s why decorating it is a high visibility job that comes with high pressure, and for wedding and event planners who know how to decorate these arch systems with style and flair, their artistry can become a signature that attracts clients and drives word of mouth advertising. We talked to ace wedding planner Will Hall of Your Wedding Solutions, Baltimore, Md., about how he decorates colonnade arch systems and how you can get the same, bold effect using your own colonnade arch system for weddings and other This traditional colonnade arch system creates an elegant focal point for weddings, prom photos and events. Here is what we learned from other events. It is manufactured by Meese Orbitron Dunne Co. in La Mirada, Calif. Mr. Hall: lodge hall or the bride’s backyard, for modern churches feel more like a Location, Location, Location example. The first step is to survey stadium. Hotels and catering halls The most important factor in the event venue or site, paying careful often use patterned wallpaper while determining how to decorate your attention to the following: other facilities may offer bare, beige colonnade arch system is the venue. -

Domestic Architecture in the Greek Colonies of the Black Sea from the Archaic Period Until the Late Hellenictic Years Master’S Dissertation

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE IN THE GREEK COLONIES OF THE BLACK SEA FROM THE ARCHAIC PERIOD UNTIL THE LATE HELLENICTIC YEARS MASTER’S DISSERTATION STUDENT: KALLIOPI KALOSTANOU ID: 2201140014 SUPERVISOR: PROF. MANOLIS MANOLEDAKIS THESSALONIKI 2015 INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY MASTER’S DISSERTATION: DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE IN THE GREEK COLONIES OF THE BLACK SEA FROM THE ARCHAIC PERIOD UNTIL THE LATE HELLENISTIC YEARS KALLIOPI KALOSTANOU THESSALONIKI 2015 [1] CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 ARCHAIC PERIOD 1.1. EARLY (610-575 BC) & MIDDLE ARCHAIC PERIOD (575-530 BC): ARCHITECTURE OF DUGOUTS AND SEMI DUGOUTS .................................................................................... 8 1.1. 1. DUGOUTS AND SEMI-DUGOUTS: DWELLINGS OR BASEMENTS? .................... 20 1.1. 2. DUGOUTS: LOCAL OR GREEK IVENTIONS? ........................................................... 23 1.1. 3. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 25 1.2. LATE ARCHAIC PERIOD (530-490/80 BC): ABOVE-GROUND HOUSES .................. 27 1.2.1 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ABOVE-GROUND HOUSES .............................................. 30 1.2.2. CONCLUSION: ............................................................................................................. 38 CLASSICAL PERIOD 2.1. EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD (490/80-450 BC): ............................................................ 43 -

Colonnade Hotel/Gatewood Apartments 1900/1911

Colonnade Hotel/Gatewood Apartments 1900/1911 107 Pine Street, Seattle, WA 197570-0600 A. A. DENNY’S 3RD ADD. 26 1 & 4 LOTS 1 AND 4 BLOCK 26, ADDITION TO THE CITY OF SEATTLE AS LAID OUT BY A. A. DENNY, COMMONLY KNOWN AS A. A. DENNY’S 3RD ADDITION TO THE CITY OF SEATTLE, ACCORDING TO THE PLAT THEREOF RE- CORDED IN VOLUME 1 OF PLATS P. 33, IN KING COUNTY WASHINGTON, EXCEPT THE WESTERLY 9 FEET THERE- OF HERETOFORE CONDEMNED IN DISTRICT COURT COUSE NUMBER 7092 FOR WIDENING OF FIRST AVENUE, AS PROVIDED UNDER ORDINANCE NUMBER 1129 OF CITY OF SEATTLE; EXCEPT FOR THE NORTHWESTERLY 7 FEET OF SAID LOT 1 HERETOFORE CONDEMNED IN KING COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT CAUSE NUMBER 57057 FOR THE WIDENING OF PINE STREET AS PROVIDED UNDER ORDINANCE NUMBER 14500 OF THE CITY OF SEATTLE. Lighthouse Investments LLC vacant 1180 South Beverly Drive, Suite 508, Los Angeles CA 90035 Stimson Brothers SRO Hotel Charles Bebb Matthew Dow Ramin Kolahi 1180 South Beverly Drive, Suite 508, Los Angeles CA 90035 (310) 556-1600 November 2016 Colonnade Hotel/Gatewood Apartments Landmark Nomination Report 107 Pine Street, Seattle, WA November 2016 Prepared by: The Johnson Partnership 1212 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-6724 206-523-1618, www.tjp.us Colonnade Hotel/Gatewood Apartments Landmark Nomination Report November 2016, page i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... -

Capitol Facts & History

Capitol facts & history History of the Legislative Building: Washington State's Legislative Building, completed in 1928 after six years of construction, serves as both a working governmental center and a symbol of Washington's free and democratic government. It is the centerpiece of the five historic capitol buildings designed by New York architects Walter Wilder and Harry White. Conceived in the architectural competition of 1911 and selected by the State Capitol Commission, Wilder and White's designs for the Legislative Building were completed and set into motion in 1922. Arguably the most impressive structure in the state, the building is comprised of more than 173 million pounds of stone, brick, concrete, and steel. The fourth tallest masonry dome in the world, rising 287 feet high, tops this magnificent edifice. The Legislative Building was a remarkable achievement founded in the era of "American Renaissance," and still stands as a symbol of American ideals and architectural grandeur. In the 78 years since its construction, the Legislative Building has housed governors, other statewide elected officials, and legislative representatives, served as the center for Washington government, and withstood the powerful impact of three major earthquakes, the most recent being the 2001 Nisqually earthquake. Through it all the building has shown remarkable resilience and strength, thanks in large part to excellent structural design, superior craftsmanship, and seismic upgrades following the earthquakes of 1949 and 1965. Yet as time has passed, numerous aspects of the building have inevitably aged and become overburdened. The structure, which originally served a state with a population scarcely over 800,000, now acts as the nucleus for a state that has over 6 million residents.