Land Policy Problems in East Asia (PART 1): Toward New Choices : A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sakura, Chiba

Coordinates: 35°43′N 140°13′E Sakura, Chiba 佐 倉 市 Sakura ( Sakura-shi) is a city located in Sakura Chiba Prefecture, Japan. 佐倉市 As of December 2014, the city has an estimated City population of 17 7 ,601, and a population density of 17 14 persons per km². The total area is 103.59 km². Contents Geography Neighboring municipalities History Economy Yuukarigaoka district of Sakura Education Transportation Railway Highway Local attractions Flag Noted people from Sakura Seal References External links Geography Sakura is located in northeastern Chiba Prefecture on the Shimōsa Plateau.[1] It is situated 40 kilometers northeast of the Tokyo and 15 kilometers from Narita International Airport. Chiba City, the prefectural capital, lies 15 kilometers southwest of Sakura. Lake Inba and the Inba Marsh form the northern city limits.[2][3] Neighboring municipalities Chiba, Chiba Location of Sakura in Chiba Prefecture Narita, Chiba Yotsukaido, Chiba Yachiyo, Chiba Inzai, Chiba Yachimata, Chiba Shisui, Chiba History The area around Sakura has been inhabited since prehistory, and archaeologists have found numerous Kofun period burial tumuli in the area, along with the remains of a Hakuho period Buddhist temple. During the Kamakura and Muromachi Sakura periods, the area was controlled by the Chiba clan. During the Sengoku period, the Chiba clan fought the Satomi clan to the south, and the Later Hōjō clan to the west. After the defeat of the Chiba clan, the area came within the control of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who assigned one of his chief generals, Doi Coordinates: 35°43′N 140°13′E Toshikatsu to rebuild Chiba Castle and to rule over Country Japan Sakura Domain as a daimyō.[2] Doi rebuilt the area Region Kantō as a jōkamachi, or castle town, which became the Prefecture Chiba Prefecture largest castle town in the Bōsō region.[1][3] Under Government the Tokugawa shogunate, Sakura Domain came to • Mayor Kazuo Warabi be ruled for most of the Edo period under the Hotta Area clan. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS How to cite: ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS (2010) Transience and durability in Japanese urban space, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/405/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Iain Robinson Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ABSTRACT The thesis addresses the research question “What is transient and what endures within Japanese urban space” by taking the material constructed form of one Japanese city as a primary text and object of analysis. Chiba-shi is a port and administrative centre in southern Kanto, the largest city in the eastern part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Region and located about forty kilometres from downtown Tokyo. The study privileges the role of process as a theoretical basis for exploring the dynamics of the production and transformation of urban space. -

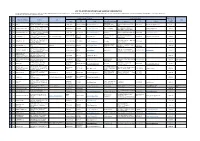

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register Summary the Clubs and Membership Figures Reflect Changes As of March 2005

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MARCH 2005 CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL DIST IDENT NBR CLUB NAME STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 5494 025243 ABIKO 333 C 4 03-2005 14 3 0 0 -2 1 15 5494 025249 ASAHI 333 C 4 03-2005 80 1 0 0 -1 0 80 5494 025254 BOSHUASAI L C 333 C 4 03-2005 15 1 0 0 -2 -1 14 5494 025255 BOSHU SHIRAHAMA L C 333 C 4 03-2005 20 1 0 0 -2 -1 19 5494 025257 CHIBA 333 C 4 03-2005 59 2 0 0 -3 -1 58 5494 025258 CHIBA CHUO 333 C 4 03-2005 30 0 0 0 0 0 30 5494 025259 CHIBA ECHO 333 C 4 03-2005 33 0 1 0 -2 -1 32 5494 025260 CHIBA KEIYO 333 C 4 03-2005 29 1 0 0 0 1 30 5494 025261 CHOSHI 333 C 4 03-2005 46 6 0 0 0 6 52 5494 025266 FUNABASHI 333 C 4 03-2005 20 2 0 0 -1 1 21 5494 025267 FUNABASHI CHUO 333 C 4 02-2005 58 17 0 0 -3 14 72 5494 025268 FUNABASHI HIGASHI 333 C 4 03-2005 27 5 0 0 -2 3 30 5494 025269 FUTTSU 333 C 4 03-2005 29 0 0 0 -2 -2 27 5494 025276 ICHIKAWA 333 C 4 03-2005 33 3 0 0 -2 1 34 5494 025277 ICHIHARA MINAMI 333 C 4 02-2005 28 2 0 0 -2 0 28 5494 025278 ICHIKAWA HIGASHI 333 C 4 03-2005 19 2 0 0 0 2 21 5494 025279 IIOKA 333 C 4 03-2005 36 2 0 0 -1 1 37 5494 025282 ICHIHARA 333 C 4 03-2005 27 1 0 0 -1 0 27 5494 025292 KAMAGAYA 333 C 4 03-2005 30 2 0 0 0 2 32 5494 025297 KAMOGAWA 333 C 4 03-2005 42 3 1 0 -4 0 42 5494 025299 KASHIWA 333 C 4 03-2005 48 0 0 0 -1 -1 47 5494 025302 BOSO KATSUURA L C 333 C 4 03-2005 67 3 1 0 -3 1 68 5494 025303 KOZAKI 333 C 4 03-2005 34 0 0 0 -2 -2 32 5494 025307 KAZUSA -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 333 C 25243 ABIKO 5 5 6 7 13 District 333 C 25249 ASAHI 0 0 2 75 77 District 333 C 25254 BOSHUASAI L C 0 0 3 11 14 District 333 C 25257 CHIBA 9 8 9 51 60 District 333 C 25258 CHIBA CHUO 3 3 4 21 25 District 333 C 25259 CHIBA ECHO 0 0 2 24 26 District 333 C 25260 CHIBA KEIYO 0 0 1 19 20 District 333 C 25261 CHOSHI 2 2 1 45 46 District 333 C 25266 FUNABASHI 4 4 5 27 32 District 333 C 25267 FUNABASHI CHUO 5 5 8 56 64 District 333 C 25268 FUNABASHI HIGASHI 0 0 0 23 23 District 333 C 25269 FUTTSU 1 0 1 21 22 District 333 C 25276 ICHIKAWA 0 0 2 36 38 District 333 C 25277 ICHIHARA MINAMI 1 1 0 33 33 District 333 C 25278 ICHIKAWA HIGASHI 0 0 2 14 16 District 333 C 25279 IIOKA 0 0 0 36 36 District 333 C 25282 ICHIHARA 9 9 7 26 33 District 333 C 25292 KAMAGAYA 12 12 13 31 44 District 333 C 25297 KAMOGAWA 0 0 0 37 37 District 333 C 25299 KASHIWA 0 0 4 41 45 District 333 C 25302 BOSO KATSUURA L C 0 0 3 54 57 District 333 C 25303 KOZAKI 0 0 2 25 27 District 333 C 25307 KAZUSA 0 0 1 45 46 District 333 C 25308 KAZUSA ICHINOMIYA L C 0 0 1 26 27 District 333 C 25309 KIMITSU CHUO 0 0 1 18 19 District 333 C 25310 KIMITSU 5 5 14 42 56 District 333 C 25311 KISARAZU CHUO 1 1 5 14 19 District 333 C 25314 KISARAZU 0 0 1 14 15 District 333 C 25316 KISARAZU KINREI 3 3 5 11 16 District 333 C 25330 MATSUDO 0 0 0 27 27 District 333 C 25331 SOBU CHUO L C 0 0 0 39 39 District 333 C -

Land Subsidence Detection by SBAS-Insar Technology and Its Factor Analysis in the Inland Area of Chiba Prefecture

HTT20-P04 Japan Geoscience Union Meeting 2019 Land subsidence detection by SBAS-InSAR technology and its factor analysis in the inland area of Chiba Prefecture *AYIHUMAIER HALIPU1, Richa Bhattarai1, Wen - LIU1, Akihiko - Kondoh1,2 1. Graduate School of Science and Engineering, 2. Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, Chiba University Land subsidence seriously influences the safety of our property. There have been many studies on the deformation of the ground surface due to the groundwater or natural gas extraction. Recently, a large amount of land subsidence had occurred in the Quaternary upland areas in the inland areas of Chiba Prefecture, Japan. There is less evidence of big wells of groundwater or natural gas, and the mechanism of subsidence is not yet clear. So far, SBAS-InSAR (Small Baseline Subset algorithm -Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar) technology had been used in the investigation process to clarify the phenomenon of land subsidence in some inland areas of Chiba Prefecture. The ALOS-PALSAR and ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 data for 2006-2010 and 2014-2018 were collected, respectively. The maps of the land subsidence phenomena in Yachimata-Tomisato area are created, and the maps reveal the spatial and temporal distribution of upland area land subsidence. The extent of the subsidence zone are almost consistent with the land survey results. Next step is to reveal the mechanism of land subsidence. At the JpGU2019, we will make a discussion on the possibility of decline of fluid pressure in deep layer. Keywords: SBAS-InSAR technology, Land subsidence, Chiba Prefecture ©2019. Japan Geoscience Union. All Right Reserved. - HTT20-P04 -. -

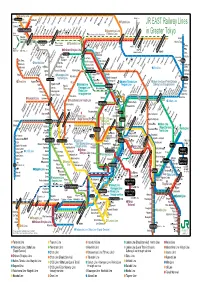

JR Railways Lines in Greater Tokyo

- 31 Joetsu- Line - Nikko- Line Shibukawa 渋川 Maebashi Kiryu Sano 32 - - Agatsuma Line Yagihara - Omata Tomita Ryomo Line oshima KomagataIsesaki Iwajuku Iwafune Tochigi JR EAST Railway Lines Kunisada Ashikaga Maebashi Yamamae Ohirashita Omoigawa Gumma-Soja 新前橋 Shim-Maebashi 17 - Utsunomiya Line Joetsu Kita- ( - ) in Greater Tokyo Shinkansen Ino KuraganoShimmachiJimboharaHonjoOkabeFukayaKagohara GyodaFukiage KonosuKonosuKitamotoOkegawaKita-AgeoAgeo Tohoku.Yamagata.Akita Shinkansen Tohoku Line KoganeiJichiidaiIshibashiSuzumenomiya Takasaki Miyahara tonyamachi Hitachi - akasaki Honjowaseda Joetsu. Nagano Hitachi-Taga 高崎 Kumagaya 18 Takasaki Line Oyama Utsunomiya Ujiie Yaita T 本庄早稲田 熊谷 Shinkansen Line Toro Kuki - Koga Nogi 小山 宇都宮 Nozaki Kuroiso Omika Omiya Shin- OkamotoHoshakuji Kataoka Nagano Higashi- Hasuda Shiraoka Higashi- 3 - Shiraoka Kurihashi Mamada 宝積寺 Tokai Shinkansen Shin-etsu Line Shonan-Shinjuku Line Kamasusaka Saitama- Karasuyama Line Nishi-NasunoNasushiobara那須塩原 Sawa odo Kawagoe Washinomiya Kita-Fujiokaansho Y orii Shintoshin T Y 川越 Omiya Suigun Line Katsuta Kodama Takezawa Nishi- Kita-Yono Yono Matsuhisa Kawagoe 大宮 Oku-Tama Gumma-Fujioka Kita-Urawa Yuki Mito 16 - Orihara Nisshin Yono-Hommachi Otabayashi Yuki Iwase Hachiko Line Ogawamachi Matoba Sashiogi Urawa Niihari Yamato Haguro Inada Shiromaru Minami-Yono Higashi- Tamado Fukuhara 水戸 Kairakuen Myokaku Kasahata Kawashima Shimodate (Extra) Hatonosu Minami-Furuya Naka-Urawa 33 Mito Line Nishi-Urawa 南浦和 Higashi-Urawa Higashi- Akatsuka Kori Ogose Musashi-Takahagi Musashi-Urawa Minami-Urawa Kawaguchi Kasama 武蔵浦和 Kawai Moro 20 Kawagoe Line Kita-Toda Warabi Shim-Misato Uchihara MitakeSawaiIkusabataFutamataoIshigamimaeHinatawadaMiyanohira 高麗川 Kita-Asaka Minami-oshigaya 友部 Ome - Toda Nishi-Kawaguchi K Komagawa Hachiko Line Yoshikawa Shishido Tomobe - Toda-Koen Kawaguchi - Misato - 14 Ome Line Higashi-Ome 4 Keihin-Tohoku- Line 23 Joban Line [Local Train]-Chiyoda Niiza - Ukimafunado 22 Iwama Kabe Higashi-Hanno 19 Saikyo- Line. -

HELLO SAKURA Kōhō-Ka (Public Relations Section), Sakura City Hall No

July 2020 7 HELLO SAKURA Kōhō-ka (Public Relations Section), Sakura City Hall No. 3 68 ☎(043) 484-1111 or (043) 484-6103; Fax:(043) 486-8720; E-mail: [email protected]; URL: http://www.city.sakura.lg.jp This is a free monthly English newsletter carrying excerpts from the Japanese newsletter Kōhō Sakura (こうほう佐倉) issued by Sakura City. For a free subscription by postal mail, please send your request via email or fax to the above email address/fax number. In general, inquiries can be answered in English on Wednesdays, in Spanish on Thursdays and in Chinese on Fridays, through Kōhō-ka, City Hall. Except for these days, questions can be answered only in Japanese at the City Hall and/or other city facilities. Therefore, when making inquiries, please be accompanied by someone who speaks Japanese. (Printed on recycled paper.) The emergency declaration regarding the new coronavirus infectious disease was canceled on May 25th but the response to prevent the spread of the infection may still take a long time. We ask you for your continued cooperation by taking preventive daily life measures. Strengthening our Medical System in preparation for 2nd and 3rd waves On May 28th, the Inba Medical Association has started the operation of a PCR test vehicle center (mobile type) to check for the presence of new coronavirus infection. The mobile center patrols Inba (The cities of Sakura, Narita, Yotsukaido, Yachimata, Inzai, Shirai, Tomisato, Shisui and Sakaemachi) collecting specimens from medical institutions of people who have been suspected of being infected. Mr. Sugenoya, Chairman of the Inba Medical Association expressed: “Since samples can be collected through this procedure, we can overcome the risk of infection problems for A demonstration was held on May medical workers as well as of lack of personal protective equipment. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

Chiba Travel

ChibaMeguri_sideB Leisure Shopping Nature History&Festival Tobu Noda Line Travel All Around Chiba ChibaExpressway Joban Travel Map MAP-H MAP-H Noda City Tateyama Family Park Narita Dream Farm MITSUI OUTLET PARK KISARAZU SHISUI PREMIUM OUTLET® MAP-15 MAP-24 Express Tsukuba Isumi Railway Naritasan Shinshoji Temple Noda-shi 18 MAP-1 MAP-2 Kashiwa IC 7 M22 Just within a stone’s throw from Tokyo by the Aqua Line, Nagareyama City Kozaki IC M24 Sawara Nagareyama IC Narita Line 25 Abiko Kozaki Town why don’t you visit and enjoy Chiba. Kashiwa 26 Sawara-katori IC Nagareyama M1 Abiko City Shimosa IC Whether it is for having fun, soak in our rich hot springs, RyutetsuNagareyamaline H 13 Kashiwa City Sakae Town Tobu Noda Line Minami Nagareyama Joban Line satiate your taste bud with superior products from the seas 6 F Narita City Taiei IC Tobu Toll Road Katori City Narita Line Shin-Matsudo Inzai City Taiei JCT Shiroi City Tonosho Town and mountains, Chiba New Town M20 Shin-Yahashira Tokyo Outer Ring Road Higashikanto Expressway Hokuso Line Shibayama Railway Matsudo City Inba-Nichi-idai Narita Sky Access Shin-Kamagaya 24 you can enjoy all in Chiba. Narita Narita Airport Tako Town Tone Kamome Ohashi Toll Road 28 34 Narita IC Musashino Line I Shibayama-Chiyoda Activities such as milking cows or making KamagayaShin Keisei City Line M2 All these conveniences can only be found in Chiba. Naritasan Shinshoji Temple is the main temple Narita International Airport Asahi City butter can be experienced on a daily basis. Narita Line Tomisato IC Ichikawa City Yachiyo City of the Shingon Sect of Chizan-ha Buddhism, Funabashi City Keisei-Sakura Shisui IC You can enjoy gathering poppy , gerbera, Additionally, there are various amusement DATA 398, Nakajima, Kisarazu-City DATA 689 Iizumi, Shisui-Town Sobu LineKeisei-Yawata Shibayama Town M21 Choshi City Isumi and Kominato railroad lines consecutively run across Boso Peninsula, through a historical Choshi 32 and antirrhinum all the year round in the TEL:0438-38-6100 TEL:043-481-6160 which was established in 940. -

The Chiba Bank, Ltd. Challenge Bank 2002

The Chiba Bank, Ltd. Challenge Bank 2002 The Chiba Bank, Ltd. Financial Results for Interim FY 2002 ended Septem ber 30, 2002 December 4, 2002 (All figures used in this document are non-consolidated, unless specifically noted otherwise.) The Chiba Bank, Ltd. Challenge Bank 2002 Table of Contents Summary of Results for the Interim Period New Medium-Term Management Plan (Outline) • Key Points of the Meeting 3 • Overview of Medium-Term Management Plan "ACT 2003"22 • Summary of Interim Results and Fiscal Year Projections 4 • New Medium-Term Management Plan, “100 Weeks of • Progress of Medium-Term Management Plan "ACT 2003" 5 Innovation and Speed” 23 • Increase in Consumer Loans 6 • Consumer Loans Appendix (1) Housing Loans 7 • Economic Conditions in Chiba Prefecture 2 (2) Auto Loans 8 • Economic Indicators for Chiba Prefecture (1)(2) 3 • Measures to Increase Lending to Corporate Customers 9 • Population of Chiba Prefecture (1)(2) 5 • Promotion of Fee-based Businesses 10 • Management Indicators 7 • Strong Increase in Stock Funds 11 • Interest Yields 8 • Active OTC Sales of Insurance 12 • Fund Management Account / Fund Raising Account 9 • Domestic Loans 10 • Expenses Reducing 13 • Domestic Deposits (1)(2) 11 • Use of IT to Enhance Service and Reduce Costs 14 • Share of Business in Chiba Prefecture 13 • Steadily Improving Loan Portfolio 15 • Investment Trusts and Foreign-Currency Deposits 14 • Support for Business Restructuring and Revitalization 16 • Loans Disclosed Under Internal Assessment and • Efforts to Remove Non-performing Loans 17 Revitalization Law Standards (1)(2) 15 • Loan Breakdown by Type of Borrower 17 • Credit-related Costs 18 • Proportion of Loans by Borrower Category 18 • FAQ on the Bad Loan Problem 19 • Factors in Decrease of Substandard Loans (1)(2) 19 • Stock Holdings and Devaluation Losses 20 • Credit costs 21 • Disposal of Collateral 22 • Land Price Trends in Chiba Prefecture (1)(2) 23 • Branch Network 25 • Composition of Stockholders 26 2 The Chiba Bank, Ltd. -

List of Approved Mongolian Sending Organization

LIST OF APPROVED MONGOLIAN SENDING ORGANIZATION [NOTE] The Sending Organization on this list is regarded as an Approved Sending Organization on the condition that "LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION FOR THE TECHNICAL INTERN TRAINEE (Reference Form 1-23)" signed and sealed by the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Mongolia is attached when applying for the accreditation of the technical intern training plan to the OTIT. Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Approved date OTIT No. Name of Organization Address URL (the date of Remarks No. name TEL Email Name of Person in Charge Address TEL Email receipt) Sukhbaatar district, 11th Human Bridge Chiba ken, Noda shi, Iwana 1-76-35 1 70 AABO LLC khoroolol,Chingis Khaan University bldg- - A. Delgermaa 99014681, 99107739 [email protected] KyodoKumiai, Assist 04-7128-7360 [email protected] 2019/3/12 Japan 406 OnePartners Cooperative #1-2, 20th building, 6th district, 11th block, 1-8-7, KANDORI, ICHIKAWA CITY, 2 77 ALTAIN KHOVOG SAIR LLC New darkhan, Darkhan uul province, - BEKHBAT Peljee -88375447 [email protected] MR.SHIINA NORIO - [email protected] 2019/3/12 CHIBA, PREF, 272-0133, JAPAN Mongolia 16-5, rashaant 11st Khoroo, Sukhbaatar 3 15 ALTAN-OCH BADRAL LLC - D.Altan-Ochir 976-98101010 [email protected] Saito Teruo Chiba ken yachimata shi enokido 458 043-442-4005 [email protected] 2019/1/10 district, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia 1-13Dari ekh, 2nd horoo, Bayanzurkh Sambuu Altantaria 7600-0130 Nihon care business 250-1 Takashina-cho,Wakaba-ku, 4 82 ALTANTOMIO -

Place Gourmet of Chiba

ChibaMeguri_sideA Chiba Prefecture’s mascot Asahi City Seashore oyster dishes MAP-37 Experience and do not miss as you are in Chiba Abalone GoGo AllAll AroundAround ChibaChiba Kinmedai (Beryx splendens) In Chiba Prefecture, abalone is harvested mainly Annual event schedule of Chiba CHI-BA+KUN It takes six to seven years to grow these natural along the coast between Isumi and Minamiboso TravelGuidebook Guide with with a RoadDrive MapMap oysters until they reach the palm size. These Kinmedai is a fish with plenty of fat. Boiling with soy sauce from May through to August. Chiba’s abalone place Gourmet oysters are harvested from May to August at features fleshiness, richly delicious taste and July (and sugar) and sashimi are popular ways of cooking January Iioka seashore and are called the "Milk of the Kinmedai. Shabushabu has also become a popular way of good resistance to teeth. Enjoy pleasant flavors Hello, I’m CHI-BA-KUN, Chiba Prefecture’s mascot Sunrise on New Year’s Day sea" because of their high nutritional value, and enjoying Kinmedai. Choshi and Katsuura are the main of the ocean. ● ● Narita Gion Festival (Narita City) character. their rich taste is exceptional. landing ports of Kinmedai in Chiba Prefecture. (Inubosaki, Kujukurihama, etc.) ● Sawara Big Festival (Katori City) Just look at me from side, and you will see my profile is of Chiba ● First visit to a shrine/temple ● Mobara Star Festival (Mobara City) Iioka Lodging Association (during the New Year period) shaped like the landform of Chiba Prefecture. DATA Spiny Lobster ● Nabaki River Raft Race 0479-57-4248 Bonito (Naritasan Shinshoji Temple, I’ll make my appearance at various points of Chiba, so please Chiba Prefecture takes top place in spiny lobster (Shirako Town) Bonito that are caught in early spring to early in summer Katori Jingu Shrine, etc.) CHIBACHIBA do not hesitate to speak to me when you come across me.