Lessons from the Tellico Dam Controversy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Nine Lakes

MELTON HILL LAKE NORRIS LAKE - 809 miles of shoreline - 173 miles of shoreline FISHING: Norris Lake has over 56 species of fish and is well known for its striper fishing. There are also catches of brown Miles of Intrepid and rainbow trout, small and largemouth bass, walleye, and an abundant source of crappie. The Tennessee state record for FISHING: Predominant fish are musky, striped bass, hybrid striped bass, scenic gorges Daniel brown trout was caught in the Clinch River just below Norris Dam. Striped bass exceeding 50 pounds also lurk in the lake’s white crappie, largemouth bass, and skipjack herring. The state record saugeye and sandstone Boone was caught in 1998 at the warmwater discharge at Bull Run Steam Plant, which bluffs awaiting blazed a cool waters. Winter and summer striped bass fishing is excellent in the lower half of the lake. Walleye are stocked annually. your visit. trail West. is probably the most intensely fished section of the lake for all species. Another Nestled in the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains, about 20 miles north of Knoxville just off I-75, is Norris Lake. It extends 1 of 2 places 56 miles up the Powell River and 73 miles into the Clinch River. Since the lake is not fed by another major dam, the water productive and popular spot is on the tailwaters below the dam, but you’ll find both in the U.S. largemouths and smallmouths throughout the lake. Spring and fall crappie fishing is one where you can has the reputation of being cleaner than any other in the nation. -

C:\Fish\Eastern Sand Darter Sa.Wpd

EASTERN SAND DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: David Grandmaison and Joseph Mayasich Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 January 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2003/40 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the eastern sand darter, Ammocrypta pellucida (Agassiz). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER................................................................... -

Information on the NCWRC's Scientific Council of Fishes Rare

A Summary of the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina Submitted by Bryn H. Tracy North Carolina Division of Water Resources North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources Raleigh, NC On behalf of the NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes November 01, 2014 Bigeye Jumprock, Scartomyzon (Moxostoma) ariommum, State Threatened Photograph by Noel Burkhead and Robert Jenkins, courtesy of the Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries and the Southeastern Fishes Council (http://www.sefishescouncil.org/). Table of Contents Page Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 3 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes In North Carolina ........... 4 Summaries from the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina .......................................................................................................................... 12 Recent Activities of NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes .................................................. 13 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part I, Ohio Lamprey .............................................. 14 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part II, “Atlantic” Highfin Carpsucker ...................... 17 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part III, Tennessee Darter ...................................... 20 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part -

A Spatial and Elemental Analyses of the Ceramic Assemblage at Mialoquo (40Mr3), an Overhill Cherokee Town in Monroe County, Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2019 COALESCED CHEROKEE COMMUNITIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPATIAL AND ELEMENTAL ANALYSES OF THE CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE AT MIALOQUO (40MR3), AN OVERHILL CHEROKEE TOWN IN MONROE COUNTY, TENNESSEE Christian Allen University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Allen, Christian, "COALESCED CHEROKEE COMMUNITIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPATIAL AND ELEMENTAL ANALYSES OF THE CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE AT MIALOQUO (40MR3), AN OVERHILL CHEROKEE TOWN IN MONROE COUNTY, TENNESSEE. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5572 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christian Allen entitled "COALESCED CHEROKEE COMMUNITIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPATIAL AND ELEMENTAL ANALYSES OF THE CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE AT MIALOQUO (40MR3), AN OVERHILL CHEROKEE TOWN IN MONROE COUNTY, TENNESSEE." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Kandace Hollenbach, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Gerald Schroedl, Julie Reed Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. -

Underwater Observation and Habitat Utilization of Three Rare Darters

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2010 Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee Robert Trenton Jett University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Jett, Robert Trenton, "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/636 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Robert Trenton Jett entitled "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. James L. Wilson, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David A. Etnier, Jason G. -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

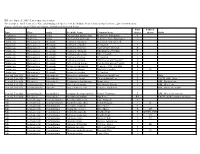

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

Spotted Darter Status Assessment

SPOTTED DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Joseph M. Mayasich and David Grandmaison Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 March 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2004-02 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the spotted darter, Etheostoma maculatum (Kirtland). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. i TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER............................................................................................................................... ii NARRATIVE ................................................................................................................................1 SYSTEMATICS............................................................................................................... -

Tennessee Lesson

TENNESSEE SOCIAL STUDIES LESSON #1 OutOut ofof thethe DarknessDarkness Topic The Tennessee Valley Authority and the Great Depression Introduction The purpose of these lessons is to introduce students to the World• War I and the Roaring Twenties (1920s-1940s) role that the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) • 5.16 Describe how New Deal policies of President Franklin played in the economic development of the South during the D. Roosevelt impacted American society with Depression. The length of these lessons can be adjusted to government-funded programs, including: Social Security, meet your time constraints. Student access to a computer lab expansion and development of the national parks, and with Internet connectivity is recommended but not required. creation of jobs. (C, E, G, H, P) Another option is for the teacher to conduct the lessons in a Tennessee in the 20th Century classroom with one computer with Internet connectivity and an LCD projector. • 5.48 Describe the effects of the Great Depression on Tennessee and the impact of New Deal policies in the state (i.e., Tennessee Valley Authority and Civilian Conservation Tennessee Curriculum Standards Corps). (C, E, G, H, P, T) These lessons help fulfill the following Tennessee Teaching Standards for: Primary Documents and Supporting Texts The 1920s • Franklin Roosevelt’s First Inaugural Address • Political cartoons about the New Deal • US.31 Describe the impact of new technologies of the era, including the advent of air travel and spread of electricity. (C, E, H) Objectives The Great Depression and New Deal • Students will identify New Deal Programs/Initiatives (TVA). -

Pelagic Larval Duration Links Life History Traits and Species Persistence in Darters (Percidae: Etheostomatinae)

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2013 Pelagic larval duration links life history traits and species persistence in Darters (Percidae: Etheostomatinae) Morgan Jessica Douglas [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Douglas, Morgan Jessica, "Pelagic larval duration links life history traits and species persistence in Darters (Percidae: Etheostomatinae). " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2410 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Morgan Jessica Douglas entitled "Pelagic larval duration links life history traits and species persistence in Darters (Percidae: Etheostomatinae)." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Christopher D. Hulsey, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Alison Boyer, James Fordyce Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Pel agic larval duration links life history traits and species persistence in Darters (Percidae: Etheostomatinae) A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Morgan Jessica Douglas August 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Jen Schweitzer, Joe Bailey, and Phillip Hollingsworth provided useful comments and encouragement. -

9The Snail Darter and the Dam最終稿.Indd

書 評 BOOK REVIEW The Snail Darter and the Dam (スネイル・ダーターとダム) Reviewed by Kazuto Oshio* and Joseph DiMento** BOOK REVIEWED: Zygmunt J. B. Plater. The Snail Darter and the Dam: How Pork-Barrel Politics Endangered a Little Fish and Killed a River. New Haven: Yale UP, 2013. When Zygmunt Plater, the author of the book under review, fi nished his job as petitioner and counsel for plaintiff citizens in the Tellico Dam case from 1974 to 1980, he looked back to his legal involvement and wrote an article in 1982. At the end of this piece he concluded: “Tellico refl ected in microcosm an amazing array of substantive issues, philosophical quandaries, human dramas, and American political artifacts” and the “Tellico case deserves a much more probing and extensive analysis than that contained in this sketch” (“Refl ected in a River” 787). Since then, he has chaired the State of Alaska Oil Spill Commission’s Legal Research Task Force, been lead author of an environmental law casebook, and has participated in numerous citizen environmental initiatives. And now, after three decades, the professor of law and director of the Land & Environmental Law Program at Boston College Law School has published The Snail Darter and the Dam: How Pork-Barrel Politics Endangered a Little Fish and Killed a River from Yale University Press. * 小塩 和人 Professor, School of Foreign Studies, Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan. ** Professor, School of Law, University of California, Irvine, U.S.A. 113 BOOK REVIEW According to Edward O. Wilson of Harvard University, this case is “the Thermopylae in the history of America’s conservation movement.” Indeed, a national poll of environmental law professors on the most important American environmental protection court decisions has ranked it the number one case (Plater, “Environmental Law” 424). -

FWS 1992 Snail Darter Species Account

Species Account SPECIES ACCOUNTS Source: Endangered and Threatened Species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book) FWS Region 4 -- As of 11/92 SNAIL DARTER (Percina (Imostoma) tanasi) FAMILY: Percidae STATUS: On October 9, 1975, this species was officially classified in the Federal Register as endangered. On July 5, 1984, the snail darter was reclassified to threatened. DESCRIPTION: The snail darter is a member of the subgenus Imostoma with characteristics most similar to the closely related stargazing darter (Percina uranida). Distinguishing characteristics of this fish are as follows: (1) modal number of anal fin rays 12; (2) pectoral and pelvic fins short and rounded; and, nuptial males with pelvic fin tubercules confined to the four median rays. The general body color is variable from brown to olive, sometimes blanched, with a dorsal saddle pattern often strongly evident. Maximum size is approximately 89 millimeters or 3.5 inches. REPRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT: Based on studies conducted in the Little Tennessee River, the spawning period is estimated to occur from mid-winter through mid-spring, and to take place in the shallower shoal areas over large, smooth gravel. Water temperature during this period ranges from 5 to 16 degrees Centigrade. Multiple spawns are suspected. Hatching takes place in about 18 to 2O days, with the larvae then drifting with the current to nursery areas farther downstream. After a nursery period of 5 to 7 months, the juvenile darters begin to migrate back to the upstream spawning areas, where they spend the remainder of the lives. About one-fourth of the darters reach sexual maturity in their first year, and the remainder during the second year. -

TEMPORARY LICENSE of PROPERTY on the FORT LOUDOUN and TELLICO DAM RESERVATIONS for CONSTRUCTION of BRIDGES OVER the TENNESSEE RIVER Loudon County, Tennessee

Document Type: EA-Administrative Record Index Field: Supplemental Environmental Assessment Project Name: Ft. Loudoun Bridge (US321) Temporary Licenses Project Number: 2013-3 TEMPORARY LICENSE OF PROPERTY ON THE FORT LOUDOUN AND TELLICO DAM RESERVATIONS FOR CONSTRUCTION OF BRIDGES OVER THE TENNESSEE RIVER Loudon County, Tennessee SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Prepared by: TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Knoxville, Tennessee August, 2013 For further information, contact: Richard L. Toennisson NEPA Interface Tennessee Valley Authority 400 West Summit Hill Drive, WT 11D Knoxville, Tennessee 37902 Phone: 865-632-8517 Fax: 865-632-3451 E-mail: [email protected] This page intentionally left blank Supplemental Environmental Assessment Purpose and Need for Action On October 22, 2012 the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) submitted an application to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) for a temporary license for the use of 6.08 acres on the Fort Loudoun Dam Reservation (FLDR) on tracts FL-1 and FL-2 and Tellico Dam Reservation (TDR) on tract TELR-103, to provide staging, haul roads, lay down areas, and install and operate temporary barge loading facilities for the construction of new bridges over the Tennessee River at River Mile (TRM) 601.8, and the Tellico canal see Attachment A. The license would allow transportation of construction material and equipment to the new bridge construction sites. The bridge construction is a major component of a larger TDOT project to upgrade U.S. Highway 321 (State Route 73) from Lenoir City, Tennessee to Blount County, Tennessee from two to four lanes in order to relieve traffic congestion and improve safety. The cost of the project is $73.3 million with 80 percent federal and 20 percent state funds.