9The Snail Darter and the Dam最終稿.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Fish\Eastern Sand Darter Sa.Wpd

EASTERN SAND DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: David Grandmaison and Joseph Mayasich Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 January 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2003/40 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the eastern sand darter, Ammocrypta pellucida (Agassiz). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER................................................................... -

Lessons from the Tellico Dam Controversy

Volume 43 Issue 4 Fall 2003 Fall 2003 Public Goods Provision: Lessons from the Tellico Dam Controversy Louis P. Cain Brooks A. Kaiser Recommended Citation Louis P. Cain & Brooks A. Kaiser, Public Goods Provision: Lessons from the Tellico Dam Controversy, 43 Nat. Resources J. 979 (2003). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol43/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. LOUIS P. CAIN & BROOKS A. KAISER* Public Goods Provision: Lessons from the Tellico Dam Controversy ABSTRACT Although absent from the initial Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973, evidence of economic considerationsfirst appeared in the 1978 amendments. The only controversial vote concerning the ESA was the one to exempt the Tellico Dam (1978). Although the dam was a local project with little expected net benefit, this article argues that broader economic considerations mattered. Working from public choice models for congressional voting decisions, a limited dependent variable regression analysis indicates the economic variables with the most explanatory power for this environmental decision are college education, poverty, the designation of critical habitat within a district, the number of endangered species in the state, dollars the state received due to earlier ESA funding, and the percentage of the district that is federal land. Comparisons with aggregated environmental votes in the same year highlight the intensity of economic considerations in the Tellico case. -

Information on the NCWRC's Scientific Council of Fishes Rare

A Summary of the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina Submitted by Bryn H. Tracy North Carolina Division of Water Resources North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources Raleigh, NC On behalf of the NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes November 01, 2014 Bigeye Jumprock, Scartomyzon (Moxostoma) ariommum, State Threatened Photograph by Noel Burkhead and Robert Jenkins, courtesy of the Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries and the Southeastern Fishes Council (http://www.sefishescouncil.org/). Table of Contents Page Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 3 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes In North Carolina ........... 4 Summaries from the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina .......................................................................................................................... 12 Recent Activities of NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes .................................................. 13 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part I, Ohio Lamprey .............................................. 14 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part II, “Atlantic” Highfin Carpsucker ...................... 17 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part III, Tennessee Darter ...................................... 20 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part -

Underwater Observation and Habitat Utilization of Three Rare Darters

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2010 Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee Robert Trenton Jett University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Jett, Robert Trenton, "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/636 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Robert Trenton Jett entitled "Underwater observation and habitat utilization of three rare darters (Etheostoma cinereum, Percina burtoni, and Percina williamsi) in the Little River, Blount County, Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. James L. Wilson, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David A. Etnier, Jason G. -

DIET CHANGES in BREEDING TAWNY OWLS &Lpar;<I>Strix Aluco</I>&Rpar;

j Raptor Res. 26(4):239-242 ¸ 1992 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. DIET CHANGES IN BREEDING TAWNY OWLS (Strix aluco) DAVID A. KIRK 1 Departmentof Zoology,2 TillydroneAvenue, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen,Scotland, U.K. AB9 2TN ABSTVO,CT.--I examinedthe contentsof Tawny Owl (Strix alucosylvatica) pellets, between April 1977 and February 1978, in mixed woodlandand gardensin northeastSuffolk, England. Six mammal, 14 bird and 5 invertebratespecies were recordedin a sample of 105 pellets. Overall, the Wood Mouse (Apodemussylvaticus) was the most frequently taken mammal prey and the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)was the mostfrequently identified bird prey. Two typesof seasonaldiet changewere found; first, a shift from mammal prey in winter to bird prey in the breedingseason, and second,a shift from smallprey in the winter to medium-sized(> 30 g) prey in the breedingseason. Contrary to somefindings elsewherein England, birds, rather than mammals, contributedsignificantly to Tawny Owl diet during the breedingseason. Cambiosen la dieta de bfihosde la especieStrix alucodurante el periodode reproduccibn EXTRACTO.--Heexaminado el contenidode egagrbpilasdel bfiho de la especieStrix alucosylvatica, entre abril de 1977 y febrerode 1978, en florestasy huertosdel norestede Suffolk, Inglaterra. Seismamlferos, catorceaves y cincoespecies invertebradas fueron registradosen una muestrade 105 egagrbpilas.En el total, entre los mamlferos,el roedorApodemus sylvaticus fue el que conmils frecuenciafue presade estos bfihos;y entre las aves,la presaidentificada con mils frecuenciafue el gorribnPasser domesticus. Dos tipos de cambib en la dieta estacionalfueron observados:primero, un cambib de clase de presa: de mamlferosen invierno a la de avesen la estacibnreproductora; y segundo,un cambiben el tamafio de las presas:de pequefiasen el inviernoa medianas(>30 g) en la estacibnreproductora. -

Ketupa Zeylonensis) Released More Than a Decade After Admission to a Wildlife Rescue Centre in Hong Kong SAR China

Survivorship and dispersal ability of a rehabilitated Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) released more than a decade after admission to a wildlife rescue centre in Hong Kong SAR China The Brown Fish Owl, Sam, in captivity at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden April 2008 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Publication Series: No 3 Survivorship and dispersal ability of a rehabilitated Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) released more than a decade after admission to a wildlife rescue centre in Hong Kong SAR China Authors Rupert Griffiths¹ and Gary Ades ¹Present Address: The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, West Hatch Wildlife Centre, Taunton, Somerset, TA 35RT, United Kingdom Citation Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden. 2008. Survivorship and dispersal ability of a rehabilitated Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) released more than a decade after admission to a wildlife rescue centre in Hong Kong SAR China. Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Publication Series No.3. Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden, Hong Kong Special Adminstrative Region. Copyright © Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Corporation Lam Kam Road, Tai Po, N.T. Hong Kong Special Adminstrative Region April 2008 ii CONTENTS Page Execuitve Summary 1 Introduction 2 Methodology 3 Results 4 Discussion 4 Acknowledgments 5 References 5 Table 7 Figures 8 iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) which had been maintained in captivity at Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden, for 11 years following its rescue, was released at a site in Sai Kung in Hong Kong on 28th November 2003. Post-release monitoring was carried out and the bird was confirmed to have survived for at least 3 months before the radio-transmitter was dropped. -

CALIFORNIA SPOTTED OWL (Strix Occidentalis Occidentalis) Jeff N

II SPECIES ACCOUNTS Andy Birch PDF of California Spotted Owl account from: Shuford, W. D., and Gardali, T., editors. 2008. California Bird Species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, California, and California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento. California Bird Species of Special Concern CALIFORNIA SPOTTED OWL (Strix occidentalis occidentalis) Jeff N. Davis and Gordon I. Gould Jr. Criteria Scores Population Trend 10 Range Trend 0 Population Size 7.5 Range Size 5 Endemism 10 Population Concentration 0 Threats 15 Year-round Range Winter-only Range County Boundaries Water Bodies Kilometers 100 50 0 100 Year-round range of the California Spotted Owl in California. Essentially resident, though in winter some birds in the Sierra Nevada descend to lower elevations, where, at least to the south, small numbers of owls also occur year round. Outline of overall range stable but numbers have declined. California Spotted Owl Studies of Western Birds 1:227–233, 2008 227 Studies of Western Birds No. 1 SPECIAL CONCERN PRIORITY occurrence: one along the west slope of the Sierra Nevada from eastern Tehama County south to Currently considered a Bird Species of Special Tulare County, the other in the mountains of Concern (year round), priority 2. Included on southern California from Santa Barbara, Ventura, the special concern list since its inception, either and southwestern Kern counties southeast to together with S. o. caurina (Remsen 1978, 2nd central San Diego County. Elevations of known priority) or by itself (CDFG 1992). -

<I>STRIX ALUCO</I>

j Raptor Res. 28(4):246-252 ¸ 1994 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. DIET OF URBAN AND SUBURBAN TAWNY OWLS (STRIX ALUCO) IN THE BREEDING SEASON ANDRZEJ ZALEWSKI Mammal ResearchInstitute, Polish Academy of Sciences,77-230 Biatowieœa, Poland ABSTI•CT.--The diet of tawny owls (Strix aluco)was studiedduring the breedingseasons 1988-90 in an urbanand a suburbanarea in Torufi, Poland.Two amphibian,18 bird,and 14 mammalspecies were recordedas prey in a sampleof 312 pellets.From 600 prey itemsfound in bothsites, the housesparrow (Passerdomesticus) was the mostfrequently taken bird prey and the commonvole (Microtus arvalis) the mostfrequently taken mammal prey. Significantlymore mammals than birdswere taken at the suburban sitethan at the urbansite (P < 0.001). At the urbansite, the proportionof birds(except for tits [Parus spp.]and housesparrows) increased over the courseof the breedingseason, while the proportionof Apodemusspp. decreased.Similarly, at the suburbansite the proportionof all birds increasedand the proportionof Microtusspp. decreased. House sparrows at the urban site and Eurasiantree sparrows (Passermontanus) and tits at the suburbansite were takenin higherproportion than their availability. An examinationof dietarystudies from elsewhere in Europeindicated that therewas a positivecorrelation betweenmean prey sizeand increasingproportion of birdsin tawny owl diets(P = 0.003). KEY WORDS: tawnyowl; diet;urban and rural area;bird selection;prey-size selection. Dieta de Strixaluco urbano y suburbanoen la estaci6nreproductiva RESUMEN.--Seestudi6 la dietade Strixaluco durante las estacionesreproductivas de 1988 a 1990 en un fireaurbana y suburbanaen Torun, Polonia.Dos antibios, 18 avesy 14 especiesde mam•ferosfueron registradoscomo presa en una muestrade 312 egagr6pilas.De 600 categorlasde presasencontradas en ambossitios, Passer domesticus rue el ave-presamils frecuentejunto al mfimfferoMicrotus arvalis. -

Seasonal Changes in Tawny Owl (Strix Aluco) Diet in an Oak Forest in Eastern Ukraine

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2017) 41: 130-137 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-1509-43 Seasonal changes in Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) diet in an oak forest in Eastern Ukraine 1, 2 Yehor YATSIUK *, Yuliya FILATOVA 1 National Park “Gomilshanski Lisy”, Kharkiv region, Ukraine 2 Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, Faculty of Biology, V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Kharkiv, Ukraine Received: 22.09.2015 Accepted/Published Online: 25.04.2016 Final Version: 25.01.2017 Abstract: We analyzed seasonal changes in Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) diet in a broadleaved forest in Eastern Ukraine over 6 years (2007– 2012). Annual seasons were divided as follows: December–mid-April, April–June, July–early October, and late October–November. In total, 1648 pellets were analyzed. The most important prey was the bank vole (Myodes glareolus) (41.9%), but the yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis) (17.8%) dominated in some seasons. According to trapping results, the bank vole was the most abundant rodent species in the study region. The most diverse diet was in late spring and early summer. Small forest mammals constituted the dominant group in all seasons, but in spring and summer their share fell due to the inclusion of birds and the common spadefoot (Pelobates fuscus). Diet was similar in late autumn, before the establishment of snow cover, and in winter. The relative representation of species associated with open spaces increased in winter, especially in years with deep snow cover, which may indicate seasonal changes in the hunting habitats of the Tawny Owl. -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

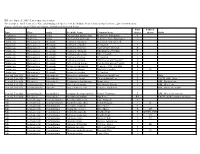

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

Strix Varia) from the Eastern United States T ⁎ Kevin D

Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 16 (2019) 100281 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vprsr Original Article Trichomonosis due to Trichomonas gallinae infection in barn owls (Tyto alba) and barred owls (Strix varia) from the eastern United States T ⁎ Kevin D. Niedringhausa, ,1, Holly J. Burchfielda,2, Elizabeth J. Elsmoa,3, Christopher A. Clevelanda,b, Heather Fentona,4, Barbara C. Shocka,5, Charlie Muisec, Justin D. Browna,6, Brandon Munka,7, Angela Ellisd, Richard J. Halle, Michael J. Yabsleya,b a Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, 589 D.W. Brooks Drive, Wildlife Health Building, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA b Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, 180 E Green Street, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA c Georgia Bird Study Group, Barnesville, GA 30204, USA d Antech Diagnostics, 1111 Marcus Ave., Suite M28, Bldg 5B, Lake Success, NY 11042, USA e Odum School of Ecology and Department of Infectious Diseases, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Trichomonosis is an important cause of mortality in multiple avian species; however, there have been relatively Owl few reports of this disease in owls. Two barn owls (Tyto alba) and four barred owls (Strix varia) submitted for Strix varia diagnostic examination had lesions consistent with trichomonosis including caseous necrosis and inflammation Tyto alba in the oropharynx. Microscopically, these lesions were often associated with trichomonads and molecular Trichomonosis testing, if obtainable, confirmed the presence of Trichomonas gallinae, the species most commonly associated Trichomonas gallinae with trichomonosis in birds. -

Spotted Darter Status Assessment

SPOTTED DARTER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Joseph M. Mayasich and David Grandmaison Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 and David Etnier Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Tennessee 569 Dabney Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-1610 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55111 March 2004 NRRI Technical Report No. NRRI/TR-2004-02 DISCLAIMER This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the spotted darter, Etheostoma maculatum (Kirtland). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this taxon should be designated as a candidate species for listing as threatened or endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act. That decision will be made by the Service after reviewing this document; other relevant biological and threat data not included herein; and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The result of the decision will be posted on the Service's Region 3 Web site (refer to: http://midwest.fws.gov/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concern.html). If designated as a candidate species, the taxon will subsequently be added to the Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web (refer to: http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Even if the taxon does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations that are contained in this document. i TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER............................................................................................................................... ii NARRATIVE ................................................................................................................................1 SYSTEMATICS...............................................................................................................