The Law of Elephants and the Justice of Monkeys: Two Cases of Anti-Colonialism in the Sudan Richard A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arianas %Riet.R;~ · Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 ~ Ews Murder in Hannon Supreme Court Lently

arianas %riet.r;~ · Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 ~ ews Murder in Hannon Supreme Court lently. The 42 year old Korean was employed at the Dallas Lounge, in Tamuning. Kennedy was found dead in sanctions AGO her apartment by police officers on Labor Day. For ignoring court orders Officers on the scene re By Zaldy Dandan General Maya Kara for a com dered AGO to show cause ported that Kennedy had bmises Variety News Staff ment, but was told that she within seven days why )ts ap on her body, head and face. THE SUPREME Court has was in a meeting. peal should not be dismissed Taitano said because the case sanctioned the Attorney This reporter's phone call for failure to prosecute. is still under investigation, he General's Office for its·fail to AGO's Criminal Division But AGO did not respond, could not disclose whether the ure to follow-up on the appeal Chief Ross Buchholz wasn't according to the court. woman was married, or the iden° Heun Sun Kennedy it filed regarding two traffic returned either. Last Aug. 13, the court is tity of friends or relatives.· cases. AGO appealed the Superior sued a second order, to which By Jacob Leon Guerrero What is known at this time is The CNMI's highest court Court's decision on CNMI vs AGO, again, did not respond. Variety News Staff that she was not an H-2 worker. dismissed AGO's appeal, and Juan D. Aguon in November "Given the fact that the gov HAGATNA, Guam - The The police department is still ordered it to pay a fine of $320. -

Closing the Gap Juanda1, Stefan Schwarze2, Stephan Von Cramon-Taubadel3 1

The Access of Microenterprises to Commercial Microcredit in Aceh Besar: Closing the Gap Juanda1, Stefan Schwarze2, Stephan von Cramon-Taubadel3 1. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Tropical and International Agriculture, Germany; 2. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Germany; 3. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Germany Introduction . Reducing poverty has become an essential part of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and need to achieve. Microenterprises (MEs) have played an important role in rural developmental activities and were long recognized as vital in poverty alleviation in Indonesia. The developing world has in fact led the way in promoting the importance of rural finance. Access to commercial services is restricted in rural areas and the services can not meet the demand for financial services by rural households. Many microenterprises belong to poor and they are unable to provide collateral. Objectives Credit Limit There were two objectives formulated in this research: . In Indonesia, the official definition of microcredit covers all loans under IDR 50 million 1. To provide a review for the gap between the number of microenterprises (approximately US$5,500). being assisted and the overall number who might need assistance. Only seven percent of microenterprises have credit limit above IDR 50 million (Figure 4). 2. To determine effect of determinant factors which were found in research Figure 4. Credit limit of MEs area to ownership of standard collateral for access to microcredit. 1% Material and Methods 7% IDR, 1 US$ ≈ IDR9000 Figure 1. Map of Aceh Besar District 10% 0 40% • The Research was >0-10 million conducted in Aceh >10-20 million Besar Dist., Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam 42% >20-50 million Prov., Indonesia. -

Urban Architecture for Sustaining Local Identity of Cultural Landscapes: a Study of Water Front Development in Khartoum, Sudan

International Journal of Development and Sustainability Online ISSN: 2168-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 4 Number 1 (2015): Pages 29-59 ISDS Article ID: IJDS14072701 Urban architecture for sustaining local identity of cultural landscapes: A study of water front development in Khartoum, Sudan Mohammad H. Refaat * Landscape Architecture Professor, Department of Urban Design Faculty of Urban & Regional Planning, Cairo University, Egypt Abstract Landscape is an indicator of common heritage as a combination of natural and cultural heritage. The of Landscape Architecture profession hosts several levels of intervention, starting from the planning level, the designing level, land suitability and water resources. This is done by applying scientific methods such as, ecological, economical, and social processes. Landscape is important as it provides the setting for our everyday lives. It is not only defined as a place of special interest nor does it refer solely to the countryside. It is the result of how people have interacted with the natural, social and cultural components of their environment and how they then perceive these. In recent years the land uses within the cities have been changing rapidly due to the various development pressures, and the tendency towards replacing all open spaces, public activities, and recreation areas to commercial and industrial uses has been enormous. The main objective of this research is to introduce an urban landscape design approach in dealing with cities waterfronts as a tool to enhance the overall sustainable the cultural landscape local identity within the urban structure of the city, taking the city of Khartoum, Sudan as a case study. -

Spatial Changes and Urban Dynamics in Tuti Island

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262049292 Spatial changes and urban dynamics in Tuti Island Conference Paper · April 2014 READS 121 2 authors, including: Ibrahim Z. Bahreldin University of Khartoum 17 PUBLICATIONS 4 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Ibrahim Z. Bahreldin Retrieved on: 16 April 2016 International Conference on the role of local communities in Disaster mitigation (Tuti as case study) International University of Africa Disaster Management and refugees Studies Institute ( DIMARSI) April 2014 Khartoum, Sudan Spatial changes and urban dynamics in Tuti Island Ibrahim Zakaria Bahreldin, Ph.D.1 Ali Mohammed Eisa, Ph.D.2 Abstract The objective of this article is to identify the key spatial, environmental and socio-economical challenges facing Tuti Island and to consider them in the context of past, present and future planning policies. The methodology underlines this article is of two folds; 1) critical literature review of both published and unpublished literature related to Tuti Island; 2) and in-depth interviews with local citizens, public officials. The interviews designed to explore their concerns regarding current planning challenges and their proposals for addressing them. Information from local and international literature has been used to contextualize the findings. This paper revealed that there is a territorial fragmentation and massive decrease of fertile agriculture land in Tuti Island. The latter observation is associated with that peoples became less attached to their homeland and therefore loosing their original identity. This article also found that both the Government and private investors see Tuti as a crossroad and potential investment place. -

ذو القعدة / ذو الحجة 1436 Issue 12 - August / September 2015

العدد 12 - ذو القعدة / ذو الحجة 1436 Issue 12 - August / September 2015 حنان باحمدان لمجلة طيران ناس 1 “اﻹنسان” أول صفات الفنان! اﻷحذية السوداء تطرد ّالبنية من 2 المدينة ّعمان.. مدينة البيوت المعلقة 3 والشبابيك ّالمعشقة سوق ّالزل.. ٌذهب ٌمشلوح على كتف 4 التاريخ يسعدني كثيراً أن أرحب بكم على متن رحلة طيران ناس. It is an immense pleasure to welcome you onboard your تعلمون أن العام 2015 يمضي إلى نهايته، وتشير النتائج إلى أن طيران ناس .flynas flight قد حقق نتائج استثنائية خﻻل هذا العام. وهناك سبب واحد لهذه النجاحات، is turning out to be an exceptional year for us and there is 2015 وهو: أنتم. نعم هذا صحيح، فأنتم - ضيوفنا الكرام - من جعلنا نمضي بعزم one simple reason for this, YOU. You - our cherished guests - have لتطوير خدماتنا والوصول إلى مستويات لم يبلغها طيران ناس من قبل، ولذلك pressed us to improve and attain award winning levels previously فإنني أعبر لكم عن عميق شكري وتقديري! !unheard of within flynas and for that I personally thank you وشهد العام الحالي كذلك إطﻻق برنامج وﻻء المسافرين “ناسمايلز”، وهو ,This year has also seen the launch of our naSmiles loyalty programme برنامج المكافآت الفريد من نوعه في قطاع الطيران بمنطقة الشرق اﻷوسط .the most generous and rewarding of its kind in the MENA aviation arena وشمال أفريقيا. ويسعدنا كثيراً أن نعلن لكم أن “ناسمايلز” يتيح لكم اﻵن تشجيع We are delighted to inform you that through naSmiles you can now فريقكم المفضل في دوري كرة القدم السعودي، كما أطلقنا عروض المزايا لكافة support your favorite Saudi football team and also that we have launched فئات أعضاء البرنامج. -

A Transformation of a Village Into a Small Town in Western Sudan

Settlement in Transition: A Transformation of a Village into a Small Town in Western Sudan Mohamed Babiker Ibrahim, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York, New York, USA E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 212-772-526 Leo C. Zulu, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences, Michigan state University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Frederick. L. (Rick) Bein, Professor, Department of Geography, Indiana University- Purdue University at Indianapolis. Indianapolis, Indiana USA. E-mail: [email protected] Final – Ready for resubmission Acknowledgements We would like to thank the people of Shubbola and our research assistant Mirgahani Awad Bashir for their hospitality and help while the lead author in the field. We thank Dana Reimer for her help. Part of his work was supported by the PSC-CUNY 40 Research Award Program at Hunter College of the City University of New York. ___________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Ibrahim, M. B., Zulu, L. C., & Bein, F. L. (2018). Settlement in Transition: a Transformation of a Village into a Small Town in Western Sudan. Urban Forum, 29(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-017-9323-2 Abstract UN-Habitat Projects Sub-Saharan Africa’s global share of the urban population to increase from 11.3 per cent in 2010 to 20.2 percent by 2050. Yet little is documented about the underlying urbanizations processes, particularly of emergence of small towns. This article uses household interviews, focus groups, observation and secondary data to examine the spontaneous transformation of a Western Sudanese village, Shubbola, into a small town. -

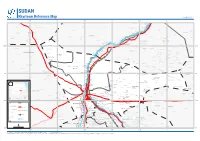

SUDAN Khartoum Reference

SUDAN Khartoum Reference Map As of May 2021 31°30'E 32°E 32°30'E 33°E 33°30'E 34°E Shaqq Ed Domi Umm Rumaylah Hambuti Wells El Qisesab El Kihek Bir Abu Hamed Qawz BurraEl Hamadab Umm Halaf Kaboshiyya Ej Jablab El Kubbo Shab Riqreiqa El Hirerab El Hosh Bir Ban Gedid El Ishab El Aqqada El Mashaykha Karabat Abu Hashim Idd Abu Inderab Id Umm AqaribEr Riqreiqa Barqat Yerga Bi'r Said En Nuqqar Tayyibah El TimerabEn Naqarab Wad Saqqa Bir Nukheila El Heleila Qoz El Wali Deim El Qarray Maghawir Qa'id Essamra Bi'r Amin Allah Burqat Al Uqul El Qiblab El Qoz Ettleh Umm Hishan Kartub El Kjera El Giwer El Doshen Sueiga El Qaff El Karada Maya Abu Firut Taragma Esh Sheikh Attayiq El Mirenab Atra El Fitrab Ad Damar Ad Dabbah Northern Esh Sheikh Al Matama Musayab Tartor Umm Garad Tartor Abdel Salamab Maya Hofra El UsharaBanatShendi El Qata Qoz Umm Maalim Al Matama Esh Shokaba El Karton Mwes Qoz El Har Fadniya Es Solat Qresh Hassani Qawz Abu Dulu Sanq At Kararat Ed Deleif Bi'r Hasanawi Bi'r Al Ajami El Bqedab El QileiaMostafa Abu Hugeiliga Mayat Jidad Qandato Es Salama El Gammam Umm Makharoqa El Qirenab Umm Guweira Idd Timreid Hobagi El Qoz Karabat Qumr Qoz El Abarib Qawz Al Abraq Kutayr Umm Shql Umm Hatab Birerab Umm Udam Qalat Hag `umar Ej JikekaEd Deim Gannetu Teras Amara Dahr El Gawad El Qaa Es Salama Island El MirekhSalamat Sallah Faraj Afandi AhmadBurug El Bafalil Jarbawiyah El Ubaiyid El Foqara Gueirin Wadi El HasarEl Azozab Berri Shrine Umm Tireif Ligheirato Ar Kaweit Salawa Qad El Habob Karabat Abu Ushar El Awatib Umm Raha Salawa Qawz Al Habashi -

Sudan National Report Habitat III, 2016

Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Urban Development National Council for Physical Development and United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-HABITAT) SUDAN’S REPORT For United Nations’ Third Conference On Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, (Habitat III), 2016 December, 2014 Photo by Hisham Karouri www.facebook.com/hishamkarouri/photos_stream?ref=page_internal Photo by Hisham Karouri Photo No 1: New urban development in the western part of Khartoum western part in the development Photo No 1: New urban 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 6 Chapter 1: Urban Demographic Issues 8 Chapter 2: Land and Urban Planning 17 Chapter 3: Environment and Urbanization 23 Chapter 4: Urban Governance and Legislation 30 Chapter 5: Urban Economy 36 Chapter 6: Housing and Basic Services 42 References 51 Annex 1: Sudan Urban Indicators 52 Annex 2: Un-Habitat‟s Urban Dwellers Survey 53 Annex 3: Importance of Urban Items to Sudanese Urban Dwellers, 2014 54 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Total and urban population in Sudan as recorded in the five population censuses 8 Table 2: Population Growth in the Largest Cities in Sudan 9 Table 3: Gender-based indicators, 2008 14 Table 4: Additional green areas in Khartoum State 15 Table 5: Areas used for vegetables production in Khartoum State, 2007-2012 19 Table 6: Assistance distributed by Khartoum State to its flood-affected residents in 2014 25 Table 7: Khartoum state's legislative council's output, 2007-2012 31 Table 8: Khartoum State cabinet output, 2007-2012 -

A Study on the Flora of Tuti Island in Khartoum State a Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award Of

ﺑﺴﻢ ﺍﷲ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ A study on the flora of Tuti Island in Khartoum state A thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Science in Botany By: Safia Abdullahi Abdelmageed Mohammed Department of Botany Faculty of Science University of Khartoum 2007 ﺑﺴﻢ ﺍﷲ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ A study on the flora of Tuti Island in Khartoum state By: Safia Abdullahi Abdelmageed Mohammed Examination Committee Name Title Signature Prof .Hassan .A.Musnad External examiner Dr.Kamal .Fadl Elseed Internal examiner Dr . Maha A. Y. Elkordofani Supervisor Table of Contents Page List of Figures, Maps and list of Appendices……………………….………………... Dedication ……………………………..................................................................... Acknowledgement ………………………................................................................ Abstract (English) …………………………………….……………………………………….… Abstract(Arabic) ………………………………………..………………………………….….. Chapter One Introduction and Literature Review……………………………………..…………..... 1 Chapter Two Description of Study area…………………………………………………………….…….. 2. 1 Geographical location………………………………..………………………….………. 2.2 Population ……………………………………………..…………………………………… 2.3 Agriculture ………………………………………………………………………………… 2.4 Topography………………………………………………………………….……………. 2.5 Geology ………………………………………………………………………………………. 2.6 Geomorphology …………………………………………………………………..……… 2.7 Soils …………………………………………………………………………………..………. 2.8 Climate (Temperature, Rainfal, Relative humidity, Wind speed) ..... Chapter Three Materials and Methods ……………………………………….………………..…………… -

![5-Moritz 942[Cybium 2016, 404]287-317.Indd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4613/5-moritz-942-cybium-2016-404-287-317-indd-6664613.webp)

5-Moritz 942[Cybium 2016, 404]287-317.Indd

Annotated checklist for fishes of the Main Nile Basin in the Sudan and Egypt based on recent specimen records (2006-2015) by Dirk NEUMANN* (1), Henriette OBERMAIER (2) & Timo MORITZ (3, 4) Abstract. – The results of several short ichthyological surveys on the Nile Basin in Sudan between 2006 and 2015 are presented. In attempting to represent major type localities and recently observed variability, we comple- ment known field records with records of a reference collection of recent fish bones collected during the 1980s and records of aberrant cichlids populations in Egypt observed at El Fayum and in lakes of the Nile Delta. From 133 native species in the Republic of the Sudan and Egypt, 107 out of 62 genera and 28 families have been con- firmed so far. The Main Nile Basin,i.e. the Sudd and all affluents to the Nile in the South Sudan and the Republic of the Sudan (White and Blue Nile, Sobat and Atbara) and all satellite waterbodies in Egypt, currently harbours 150 species. This count includes 10 “abberant” populations putatively representing distinct species, namely Garra cf. vinciguerrae, G. sp. nov. “flathead”, G. sp. “Sennar”, Haplochromis sp. “Delta1”, H. sp. “Delta2” and H. sp. “Fayum”, Hemichromis cf. letourneuxi “Birkat Abu Jumas”, Micropanchax cf. loati, Poropanchax © SFI cf. normani, and Chiloglanis sp. “Sennar”. Two local populations, Sarotherodon galilaeus (Mariut) and Labeo Received: 18 Aug. 2015 forskalii (Sennar), seem different but are not included to the count of “abberant” populations because of the high Accepted: 1 Dec. 2016 overall variability in these two species in general and intermediate populations that have been observed along the Editor: H. -

Khartoum, Sudan by Dr

The case of Khartoum, Sudan by Dr. Galal Eldin Eltayeb Contact: Dr. Galal Eldin Eltayeb Department of Geography Source: CIA factbook Faculty of Arts University of Khartoum Sudan Tel. +249- 11- 226582 (Res) Fax.+249- 11- 776080 Email: [email protected] [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. National Overview Rapid, unorganised, sometimes unauthorised urban In terms of general socio-economic development, the growth (urban sprawl) has become a prominent feature vast area of the country and transport difficulties have of developing countries, and the Sudan is no exception. encouraged the emergence and subsequent growth of This urban growth is generally measured by increases regional and local urban centres. Table 2 shows how in area and density more than by functional develop- differently the various major urban centres have grown, ment. Rural mass exodus to Sudanese urban centres is and how the rate of growth varied over time for each of attributed mainly to geographically and socially uneven them. Variations in the rate of growth reflect the general development and the concomitant depression of rural urbanisation trend and, more importantly, the regional ecosystems and communities, the long civil war and and local factors pertaining to population displacement, armed conflicts, natural disasters like drought and eg natural hazards in the east and west, famine in the famine, and the failure of government economic poli- cies. The number of displaced people has been esti- mated by the Commission for Relief and Rehabilitation Table 1: Total and Urban Populations (000s), Sudan, 1955-2002 at 4,104,970 of whom 1.8 million are in Greater Khartoum (El Battahani et al, 1998: 42-3) and about 2 million others are in other urban centres. -

The Islamic Policies of the Sudan Government, 1899 - 1924

Durham E-Theses The Islamic policies of the Sudan Government, 1899 - 1924 Rahman, M.M. How to cite: Rahman, M.M. (1967) The Islamic policies of the Sudan Government, 1899 - 1924, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9553/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT OP THE THESIS • THE ISLMIC POLICIES OF THE SUDAN G<JVERHBENTt 1899-192^. By 1. ABSTRACT* The present w>rk intends to study tho policy that the Anglor Option ruler$ adopted tosards Islam when their joint mile was established in the Sudan, in 1899. She period covered by the study ie extended from 1899 to 192W Besides an introduction and the oonoluaion the main body of the work has been divided into six chapters. For convenience, each chapter has been sub-divided into sections.