Does Aid Motivate Democracy? a Preliminary Study on Official Development Assistance and Regime Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 A.M

Carleton University Fall 2019 Department of Political Science Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 a.m. – 2:25 p.m. Please confirm location on Carleton Central Instructor: Professor Achim Hurrelmann Office: D687 Loeb Building Office Hours: Mondays, 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m., and by appointment Phone: (613) 520-2600 ext. 2294 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @achimhurrelmann Course description: Over the past seventy years, European integration has made significant contributions to peace, economic prosperity and cultural exchange in Europe. By contrast, the effects of integration on the democratic quality of government have been more ambiguous. The European Union (EU) possesses more mechanisms of democratic input than any other international organization, most importantly the directly elected European Parliament (EP). At the same time, the EU’s political processes are often described as insufficiently democratic, and European integration is said to have undermined the quality of national democracy in the member states. Concerns about a “democratic deficit” of the EU have not only been an important topic of scholarly debate about European integration, but have also constituted a major argument of populist and Euroskeptic political mobilization, for instance in the “Brexit” referendum. This course approaches democracy in the EU from three angles. First, it reviews the EU’s democratic institutions and associated practices of citizen participation: How -

Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna

Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond 2 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 July 1997 Prof. Dr. Larry Diamond Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 USA e-mail: [email protected] and International Forum for Democratic Studies National Endowment for Democracy 1101 15th Street, NW, Suite 802 Washington, DC 20005 USA T 001/202/293-0300 F 001/202/293-0258 Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. It includes papers by the Department’s teaching and research staff, visiting professors, students, visiting fellows, and invited participants in seminars, workshops, and conferences. As usual, authors bear full responsibility for the content of their contributions. All rights are reserved. Abstract The “Third Wave” of global democratization, which began in 1974, now appears to be drawing to a close. While the number of “electoral democracies” has tripled since 1974, the rate of increase has slowed every year since 1991 (when the number jumped by almost 20 percent) and is now near zero. -

THE RISE of COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A

Elections Without Democracy THE RISE OF COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way Steven Levitsky is assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. His Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Lucan A. Way is assistant professor of political science at Temple University and an academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the obstacles to authoritarian consolidation in the former Soviet Union. The post–Cold War world has been marked by the proliferation of hy- brid political regimes. In different ways, and to varying degrees, polities across much of Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbab- we), postcommunist Eurasia (Albania, Croatia, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine), Asia (Malaysia, Taiwan), and Latin America (Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru) combined democratic rules with authoritarian governance during the 1990s. Scholars often treated these regimes as incomplete or transi- tional forms of democracy. Yet in many cases these expectations (or hopes) proved overly optimistic. Particularly in Africa and the former Soviet Union, many regimes have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. It may therefore be time to stop thinking of these cases in terms of transitions to democracy and to begin thinking about the specific types of regimes they actually are. In recent years, many scholars have pointed to the importance of hybrid regimes. Indeed, recent academic writings have produced a vari- ety of labels for mixed cases, including not only “hybrid regime” but also “semidemocracy,” “virtual democracy,” “electoral democracy,” “pseudodemocracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “semi-authoritarianism,” “soft authoritarianism,” “electoral authoritarianism,” and Freedom House’s “Partly Free.”1 Yet much of this literature suffers from two important weaknesses. -

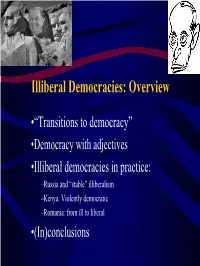

Illiberal Democracies: Overview

Illiberal Democracies: Overview •“Transitions to democracy” •Democracy with adjectives •Illiberal democracies in practice: –Russia and “stable” illiberalism –Kenya: Violently democratic –Romania: from ill to liberal •(In)conclusions “Transitions to democracy” • Transitions literature comes out of a reading of democratization in L.Am., ‘70s & ‘80s. • Mechanisms of transition (O’Donnell and Schmitter): – Splits appear in the authoritarian regime – Civil society and opposition develop – “Pacted” transitions Democracy with Adjectives • Problem: The transitions model is excessively teleological and just inaccurate • “Illiberal” meets “democracy” – What is democracy (again, and in brief)? – Why add “liberal”? – What in an illiberal democracy is “ill”? A Typology of Regimes Chart taken from Larry Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes” Journal of Democracy 13: 2 (2002) How do “gray zone” regimes develop? • Thomas Carothers: Absence of pre-conditions to democracy, which is tied to… (Culturalist) • Fareed Zakaria: When baking a liberal democracy, liberalize then democratize (Institutionalist). • Michael McFaul: Domestic balance of power at the outset matters (path dependence). Where even, illiberalism may develop (Rationalist). Russia Poland Case studies: Russia • 1991-93: An even balance of power between Yeltsin and reformers feeds into political ambiguity…and illiberalism • After Sept 1993 - Yeltsin takes the advantage and uses it to shape Russia into a delegative democracy • The creation of President Putin • Putin and the “dictatorship of law” -

International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding

The Unintended Consequences of Democracy Promotion: International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anna M. Meyerrose, M.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Alexander Thompson, Co-Advisor Irfan Nooruddin, Co-Advisor Marcus Kurtz William Minozzi Sara Watson c Copyright by Anna M. Meyerrose 2019 Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, international organizations (IOs) have engaged in unprecedented levels of democracy promotion and are widely viewed as positive forces for democracy. However, this increased emphasis on democracy has more re- cently been accompanied by rampant illiberalism and a sharp rise in cases of demo- cratic backsliding in new democracies. What explains democratic backsliding in an age of unparalleled international support for democracy? Democratic backsliding oc- curs when elected officials weaken or erode democratic institutions and results in an illiberal or diminished form of democracy, rather than autocracy. This dissertation argues that IOs commonly associated with democracy promotion can support tran- sitions to democracy but unintentionally make democratic backsliding more likely in new democracies. Specifically, I identify three interrelated mechanisms linking IOs to democratic backsliding. These organizations neglect to support democratic insti- tutions other than executives and elections; they increase relative executive power; and they limit states’ domestic policy options via requirements for membership. Lim- ited policy options stunt the development of representative institutions and make it more difficult for leaders to govern. Unable to appeal to voters based on records of effective governance or policy alternatives, executives manipulate weak institutions to maintain power, thus increasing the likelihood of backsliding. -

Islam and Democracy: Is Modernization a Barrier? John O

Religion Compass 1/1 (2007): 170±178, 10.1111/j. 1749-8171.2006.00017.x Islam and Democracy: Is Modernization a Barrier? John O. Voll Georgetown University Abstract The relationship between Islam and democracy is a hotly debated topic. Usually the disagreements are expressed in a standard form. In this form, the debaters' definitions of ªIslamº and ªdemocracyº determine the conclusions arrived at. It is possible, depending upon the definitions used, to ªproveº both positions: Islam and democracy are compatible and that they are not. To escape from the predefined conclusions, it is necessary to recognize that ªIslamº and ªdemocracyº are concepts with many definitions. In the twenty-first century, important interpretations of Islam open the way for political visions in which Islam and democracy are mutually supportive. Does religion represent an obstacle to modernization and democratization? Does religion pose a threat to democracy if a democratically elected govern- ment becomes a ªtheocracyº? Does the majority rule of democracy threaten the liberty and freedom of other members of a society? If the majority imposes its will upon minorities, is that a departure from democracy in general or form of ªliberalº democracy? Does modernization strengthen or inhibit democratization and individual liberty? These broad questions are being debated in many different contexts around the world. They provide a framework for looking at the experience of Muslim societies and the relationships between Islam and democracy. Tensions between democracy and liberty -

A Theory of Independent Courts in Illiberal Democracies

A Theory of Independent Courts in Illiberal Democracies Nuno Garoupa∗ Leyla D. Karakas† March 1, 2018 Abstract Illiberal democracies are on the rise. While such political regimes have eliminated important institutional constraints on executive power, they tend to feature an oc- casionally defiant judiciary. We provide a novel explanation for this phenomenon by focusing on the judiciary's role as a potential provider of valuable information to the executive about divisions within the regime's elites. The model features an office-motivated executive that balances the conflicting interests of the voters and the elites in determining a redistribution policy and the type of judicial review this policy will be subject to. An independent judiciary is observed in equilibrium only if the resulting revelation on the strength of the elites would be sufficiently informative for the executive to warrant reneging on its ex ante optimal policy. Intuitively, in the absence of a strong legislative opposition or a free media, a degree of judicial independence helps the survival of the nondemocratic regime by more informatively balancing the interests of the voters and the elites. We conclude by discussing in- stitutional and welfare implications. Our results contribute to the debates on the survival of independent political institutions in authoritarian regimes. Keywords : Authoritarian regimes; Judicial independence; Rent-seeking. JEL Classification : D72; D78; P48. ∗School of Law, Texas A&M University, Fort Worth, TX 76102. Email: [email protected]. †Department of Economics, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244. Email: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction Independent courts are perceived as being intrinsic to democracy. -

Populism, Nationalism and Illiberalism: a Challenge for Democracy and Civil Society

INSTITUTE E-PAPER A Companion to Democracy #2 Populism, Nationalism and Illiberalism: A Challenge for Democracy and Civil Society ANNA LÜHRMANN AND SEBASTIAN HELLMEIER V-DEM INSTITUTE, GOTHENBURG A Publication of Heinrich Böll Foundation, February 2020 Preface to the e-paper series “A Companion to Democracy” Democracy is multifaceted, adaptable – and must constantly meet new challenges. Democratic systems are influenced by the historical and social context, by a country’s geopolitical circumstances, by the political climate and by the interaction between institutions and actors. But democracy cannot be taken for granted. It has to be fought for, revitalised and renewed. There are a number of trends and challenges that affect democracy and democratisation. Some, like autocratisation, corruption, the delegitimisation of democratic institutions, the shrinking space for civil society or the dissemination of misleading and erroneous information, such as fake news, can shake democracy to its core. Others like human rights, active civil society engagement and accountability strengthen its foundations and develop alongside it. The e-paper series “A Companion to Democracy” examines pressing trends and challenges facing the world and analyses how they impact democracy and democratisation. Populism, Nationalism and Illiberalism: A Challenge for Democracy and Civil Society 2/ 34 Populism, Nationalism and Illiberalism: A Challenge for Democracy and Civil Society Anna Lührmann and Sebastian Hellmeier 3 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Populism, nationalism and illiberalism as a challenge for democracy 6 2.1. Illiberalism in the 21st century 6 2.2. Illiberalism and populism 11 2.3. Accelerants: nationalism and polarisation 13 2.4. Democracy in times of growing populism and nationalism 15 3. -

Hybrid Regimes and the Challenges of Deepening and Sustaining Democracy in Developing Countries1 Alina Rocha Menocala* and Verena Fritzb with Lise Raknerc

South African Journal of International Affairs Vol. 15, No. 1, June 2008, 29Á40 Hybrid regimes and the challenges of deepening and sustaining democracy in developing countries1 Alina Rocha Menocala* and Verena Fritzb with Lise Raknerc aOverseas Development Institute, London, UK; bPoverty Reduction and Economic Management Network, World Bank, Washington, DC, USA; cChr. Michelsen Institute and the University of Bergen, Norway A wave of democratisation swept across the developing world from the 1980s onwards. However, despite the momentous transformation that this so-called ‘Third Wave’ has brought to formal political structures in regions ranging from Africa to Asia to Latin America, only a limited number of countries have succeeded in establishing consolidated and functioning democratic regimes. Instead, many of these new regimes have become stuck in transition, combining a rhetorical acceptance of liberal democracy with essentially illiberal and/or authoritarian traits. This article analyses the emergence and key characteristics of these ‘hybrid regimes’ and the challenges of democratic deepening. It suggests that, because a broad consensus to uphold democracy as the ‘only game in town’ is lacking, hybrid regimes tend to be unstable, unpredictable, or both. The article concludes by arguing that a deeper understanding of the problems besetting these regimes helps to provide a more realistic assessment of what these incipient and fragile democracies can be expected to achieve. Keywords: democratisation; democratic consolidation; hybrid regimes; formal institutions; informal institutions; Africa; Latin America Understanding the ‘Third Wave’ of democratisation A wave of democratisation originating in Portugal and Spain in the 1970s swept across the developing world in the 1980s and 1990s. -

1 THEBUDHHIST LAW 22 and 23 May 2016 in Thailand by Justice

THEBUDHHIST LAW 22nd and 23rd May 2016 in Thailand By Justice Sonam Tobgye, Former Chief Justice of Bhutan Introduction Buddhism is not only a religion and philosophy but includes enlightened laws. They are progressive and modern. They are not restrained by ages, not constrained by geography and not restricted by races (racial feelings - jati-vitakka, national feelings - janapada-vitakka and egotism or personal and national pride - avannatti).The first word of Buddha was: “I shall go to Banaras where I will light the lamp that will bring light unto the world. I will go to Banaras and beat the drums that will awaken humankind. I shall go to Banaras and there I shall teach the Law.”1 What is law? Dynamic intelligence, speculative minds, common misery of pain and shared anguish made the human search for law and justice. Human aspired for salvation and liberation through spiritual, philosophical and intellectual pursuit to unlock the mysteries and expose the truth. The quest for law was one of them. Therefore, the history of natural law enshrines that the Greeks gave a conception of universal law for all mankind under which all men are equal and which is binding on all people. Two trends of thought existed among them. Firstly, the Sophists developed a skepticism in which they recognized the relativity of human ideas and rejected absolute standards. The basis of law was the self-interest of the lawmaker and the only reason for obedience to law was the self-interest of the subject. Secondly, according to other schools of thought, law was guided by uniform principles, which could provide stability. -

Public Participation in an Illiberal Democracy

Otto Spijkers Public participation in an illiberal democracy What place is left for critical citizens to influence policy There are essentially three ways for a government to making in an illiberal democracy? And how are the respond, and these will be addressed in turn. First, the authorities likely to respond to such calls for public government can suppress critical citizens, even label participation? This essay explores three scenarios: them as enemies of the state, and imprison them or (1) critical citizens can be suppressed and persecuted by worse. This scenario is analysed briefly in the next section. the government; (2) they can be encouraged to use whatever is left of existing democratic institutions to The second option for the government is to refer critical influence public policy; or (3) they can be invited by the citizens to existing democratic institutions as the means government to participate directly in public policymaking to influence public policy, i.e. to remind them that they through such instruments as referenda or public live in a democracy, and that they may establish their consultations. Leaders in illiberal democracies know this, own political party, get themselves elected, and become and will use it to their advantage. involved in politics in this traditional way. Introduction 1 The third and final option is to welcome the direct When democracies become more illiberal, civil liberties participation of active citizens in public policymaking, decline and the space for civil society shrinks. What and look at ways to involve them directly in public possibilities are left for critical citizens to influence policymaking by organizing referenda, public policymaking in an illiberal democracy? This essay consultations, etc. -

Democracy, Diversity, and Schooling

by Walter C. Parker from The Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education, J. A. Banks, ed. (New York: Sage, 2012) DEMOCRACY, DIVERSITY, AND SCHOOLING Democracy, specifically liberal democracy, is a form of government and mode of living with others—making decisions about public problems, distributing resources, resolving conflict, and planning for the future. Key characteristics are popular sovereignty, majority will, civil rights and liberties, the rule of law (constitutionalism), and free and fair elections. Diversity refers to the fact that people in society differ by ideology, social class, race, language, culture, gender, religion, sexual orientation, citizenship status, and other consequential social categories—consequential because privilege or discrimination result from one’s position in these categories. In societies aiming to be liberal democracies, schooling brings democracy and diversity together because schools have diverse student bodies, more or less, because schools have problems, and because schools are charged with educating citizens for democratic life. Together, these resources—diversity, problems, and mission—can be mobilized for democratic education, but not without difficulty or limits. Overview This entry has two main sections. The first, “Democracy and Diversity,” explains democracy—more precisely liberal democracy or republic—and its relationship to diversity. The second, “Schooling,” presents the assumptions that legitimize and shape efforts to educate students for democratic life. This section has three sub-sections. “Education for Democracy” explains why schools may be the best available social sites for educating democratic citizens for enlightened democratic engagement. “Discursive Approaches” demonstrates how instructional strategies involving classroom discussion are pertinent to this end. “Tensions and Limits” concludes this entry. Democracy and Diversity Liberal democracy is a profound political achievement for those who value diversity.