Democratic Transitions, Institutional Strength, and War Edward D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aggressive Behaviors Within Politics, 1948-1962: a Cross-National Study," Journal of Conflict Resolution 10, No.3 (September 1966): 249-270

NOTES 1 INTRODUCTION: CONTENDING VIEWS-MILITARISM, MILITARIZATION AND WAR 1. Ivo Feierabend and Rosalind Feierabend, "Aggressive Behaviors within Politics, 1948-1962: A Cross-National Study," Journal of Conflict Resolution 10, no.3 (September 1966): 249-270. 2. Patrick Morgan, "Disarmament," in Joel Krieger, ed., The Oxford Companion to the Politics of the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993),246. 3. Stuart Bremer, "Dangerous Dyads: Conditions Mfecting the Likelihood of Interstate War, 1816-1965," Journal of Conflict Resolution 36, no.2 (June 1992): 309-341,318,330; The remainder of Bremer's study has to do with the impact of military spending and not with variations caused by regime type. 4. Thomas Lindemann and Michel Louis Martin, "The Military and the Use of Force," in Giuseppe Caforio, ed., Handbook of the Sociology of the Military (New York: Kluwer, 2003),99-109,104-109. 5. Alfred Vagts, Defense and Diplomacy-The Soldier and the Conduct of Foreign Relations (New York: King Crown's Press, 1958), 3. The concept was subsequently applied by Herbert Spencer, Otto Hintze, and Karl Marx. See Volker Berghahn, Militarism: The History of an International Debate, 1861-1979 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984). 6. Herbert Spencer, Principles of Sociology, Stanislav Andreski, ed. (London: Macmillan, 1969): 499-571. 7. Felix Gilbert, ed., The Historical Essays of Otto Hintze (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 199. 8. Karl Liebknecht, Militarism (Toronto: William Briggs, 1917); Berghahn, 18,23,25. 9. James Donovan, Militarism U.S.A. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970),25. 10. Berghahn, 19. 11. Dan Reiter and Allan Starn, "IdentifYing the Culprit: Democracy, Dictatorship, and Dispute Initiation," American Political Science Review 97, no.2 (May 2003): 333-337; see also R. -

PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 A.M

Carleton University Fall 2019 Department of Political Science Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 a.m. – 2:25 p.m. Please confirm location on Carleton Central Instructor: Professor Achim Hurrelmann Office: D687 Loeb Building Office Hours: Mondays, 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m., and by appointment Phone: (613) 520-2600 ext. 2294 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @achimhurrelmann Course description: Over the past seventy years, European integration has made significant contributions to peace, economic prosperity and cultural exchange in Europe. By contrast, the effects of integration on the democratic quality of government have been more ambiguous. The European Union (EU) possesses more mechanisms of democratic input than any other international organization, most importantly the directly elected European Parliament (EP). At the same time, the EU’s political processes are often described as insufficiently democratic, and European integration is said to have undermined the quality of national democracy in the member states. Concerns about a “democratic deficit” of the EU have not only been an important topic of scholarly debate about European integration, but have also constituted a major argument of populist and Euroskeptic political mobilization, for instance in the “Brexit” referendum. This course approaches democracy in the EU from three angles. First, it reviews the EU’s democratic institutions and associated practices of citizen participation: How -

Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna

Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond 2 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 July 1997 Prof. Dr. Larry Diamond Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 USA e-mail: [email protected] and International Forum for Democratic Studies National Endowment for Democracy 1101 15th Street, NW, Suite 802 Washington, DC 20005 USA T 001/202/293-0300 F 001/202/293-0258 Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. It includes papers by the Department’s teaching and research staff, visiting professors, students, visiting fellows, and invited participants in seminars, workshops, and conferences. As usual, authors bear full responsibility for the content of their contributions. All rights are reserved. Abstract The “Third Wave” of global democratization, which began in 1974, now appears to be drawing to a close. While the number of “electoral democracies” has tripled since 1974, the rate of increase has slowed every year since 1991 (when the number jumped by almost 20 percent) and is now near zero. -

THE RISE of COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A

Elections Without Democracy THE RISE OF COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way Steven Levitsky is assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. His Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Lucan A. Way is assistant professor of political science at Temple University and an academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the obstacles to authoritarian consolidation in the former Soviet Union. The post–Cold War world has been marked by the proliferation of hy- brid political regimes. In different ways, and to varying degrees, polities across much of Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbab- we), postcommunist Eurasia (Albania, Croatia, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine), Asia (Malaysia, Taiwan), and Latin America (Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru) combined democratic rules with authoritarian governance during the 1990s. Scholars often treated these regimes as incomplete or transi- tional forms of democracy. Yet in many cases these expectations (or hopes) proved overly optimistic. Particularly in Africa and the former Soviet Union, many regimes have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. It may therefore be time to stop thinking of these cases in terms of transitions to democracy and to begin thinking about the specific types of regimes they actually are. In recent years, many scholars have pointed to the importance of hybrid regimes. Indeed, recent academic writings have produced a vari- ety of labels for mixed cases, including not only “hybrid regime” but also “semidemocracy,” “virtual democracy,” “electoral democracy,” “pseudodemocracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “semi-authoritarianism,” “soft authoritarianism,” “electoral authoritarianism,” and Freedom House’s “Partly Free.”1 Yet much of this literature suffers from two important weaknesses. -

International Conflict PS 9450 114 Arts and Science R 6:00-8:30 Fall 2020 University of Missouri

International Conflict PS 9450 114 Arts and Science R 6:00-8:30 Fall 2020 University of Missouri Syllabus Dr. Stephen L. Quackenbush Office: 305 Professional Building Phone: 882-2082 Office Hours: by appointment (zoom) Email: [email protected] Course Description and Objectives: The purpose of this graduate seminar is to analyze important theories regarding the causes of international conflict and war. This course will: (a) introduce students to a wide range of research on international conflict (focusing on quantitative and formal research) and (b) develop students’ ability to critically evaluate research, and consequently how to design and execute their own research projects. Books (available at University Bookstore): Required: Horowitz, Michael C., Allan C. Stam, and Cali M. Ellis. 2015. Why Leaders Fight. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Quackenbush, Stephen L. 2015. International Conflict: Logic and Evidence. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Sechser, Todd S., and Matthew Fuhrmann. 2017. Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Weeks, Jessica L. P. 2014. Dictators at War and Peace. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Zagare, Frank C. 2011. The Games of July: Explaining the Great War. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Recommended: Mitchell, Sara McLaughlin, Paul F. Diehl, and James D. Morrow, ed. 2012. Guide to the Scientific Study of International Processes. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. 1 Coursework and Grading: Participation: The quality of a graduate level seminar depends to -

The University of Texas at Austin Government 388K (39090) Study of International Relations Fall 2014, T Th 2-3.30, CAL 323

The University of Texas at Austin Government 388K (39090) Study of International Relations Fall 2014, T Th 2-3.30, CAL 323 Patrick J. McDonald BAT 4.136 512.232.1747 [email protected] Office hours: T 9.30-10.30, 3.30-4.00; Th 1-2, 3.30-4.00 DESCRIPTION This graduate course on the study of international relations will survey some of the most prominent contributions to the field during the past thirty years. It is designed to help you prepare to take the Ph.D. preliminary exams for the IR subfield in the Government Department and to help you prepare to execute your own original research projects. To these ends, the course will provide a broad theoretical overview of the field of international relations. The substance of the course is conceptually organized around the question of how social order is constructed and sustained in the international system. Our discussions of theory will focus on the following sources of order: balance of power, hegemony, technology, ideas, norms, international organizations, globalization, and domestic regime type. COURSE REQUIREMENTS There will be four key requirements for this course. First, you will be expected to attend class, keep up with the assigned readings, and participate in our discussions. Second, you will write a series (about 12) of short weekly papers. Third, designed to set up a future research paper, you will write a review of some body of IR literature of your choice. Fourth, during the final exam period, you will turn in an extended “brainstorming” paper that revises one of your weekly writing assignments. -

How Smart and Tough Are Democracies? Reassessing

How Smart and Tough Are Democracies? How Smart and Tough Alexander B. Downes Are Democracies? Reassessing Theories of Democratic Victory in War The argument that de- mocracies are more likely than nondemocracies to win the wars they ªght— particularly the wars they start—has risen to the status of near-conventional wisdom in the last decade. First articulated by David Lake in his 1992 article “Powerful Paciªsts,” this thesis has become ªrmly associated with the work of Dan Reiter and Allan Stam. In their seminal 2002 book, Democracies at War, which builds on several previously published articles, Reiter and Stam found that democracies win nearly all of the wars they start, and about two-thirds of the wars in which they are targeted by other states, leading to an overall suc- cess rate of 76 percent. This record of democratic success is signiªcantly better than the performance of dictatorships and mixed regimes.1 Reiter and Stam offer two explanations for their ªndings. First, they argue that democracies win most of the wars they initiate because these states are systematically better at choosing wars they can win. Accountability to voters gives democratic leaders powerful incentives not to lose wars because defeat is likely to be punished by removal from ofªce. The robust marketplace of ideas in democracies also gives decisionmakers access to high-quality informa- tion regarding their adversaries, thus allowing leaders to make better deci- sions for war or peace. Second, Reiter and Stam argue that democracies are superior war ªghters, not because democracies outproduce their foes or overwhelm them with powerful coalitions, but because democratic culture produces soldiers who are more skilled and dedicated than soldiers from non- Alexander B. -

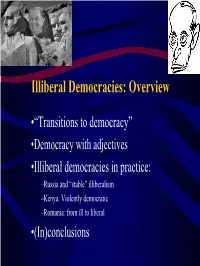

Illiberal Democracies: Overview

Illiberal Democracies: Overview •“Transitions to democracy” •Democracy with adjectives •Illiberal democracies in practice: –Russia and “stable” illiberalism –Kenya: Violently democratic –Romania: from ill to liberal •(In)conclusions “Transitions to democracy” • Transitions literature comes out of a reading of democratization in L.Am., ‘70s & ‘80s. • Mechanisms of transition (O’Donnell and Schmitter): – Splits appear in the authoritarian regime – Civil society and opposition develop – “Pacted” transitions Democracy with Adjectives • Problem: The transitions model is excessively teleological and just inaccurate • “Illiberal” meets “democracy” – What is democracy (again, and in brief)? – Why add “liberal”? – What in an illiberal democracy is “ill”? A Typology of Regimes Chart taken from Larry Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes” Journal of Democracy 13: 2 (2002) How do “gray zone” regimes develop? • Thomas Carothers: Absence of pre-conditions to democracy, which is tied to… (Culturalist) • Fareed Zakaria: When baking a liberal democracy, liberalize then democratize (Institutionalist). • Michael McFaul: Domestic balance of power at the outset matters (path dependence). Where even, illiberalism may develop (Rationalist). Russia Poland Case studies: Russia • 1991-93: An even balance of power between Yeltsin and reformers feeds into political ambiguity…and illiberalism • After Sept 1993 - Yeltsin takes the advantage and uses it to shape Russia into a delegative democracy • The creation of President Putin • Putin and the “dictatorship of law” -

STILL LOOKING for AUDIENCE COSTS Erik Gartzke and Yonatan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository STILL LOOKING FOR AUDIENCE COSTS Erik Gartzke and Yonatan Lupu Eighteen years after publication of James Fearon’s article stressing the importance of domestic audience costs in international crisis bargaining, we continue to look for clear evidence to support or falsify his argument. 1 Notwithstanding the absence of a compelling empirical case for or against audience costs, much of the discipline has grown fond of Fearon’s basic framework. A key reason for the importance of Fearon’s claims has been the volume of theories that build on the hypothesis that leaders subject to popular rule are better able to generate audience costs. Scholars have relied on this logic, for example, to argue that democracies are more likely to win the wars they fight, 2 that democracies are more reliable allies, 3 and as an explanation for the democratic peace. 4 A pair of recent studies, motivated largely by limitations in the research designs of previous projects, offers evidence the authors interpret as contradicting audience cost theory. 5 Although we share the authors’ ambivalence about audience costs, we are not convinced by their evidence. What one seeks in looking for audience costs is evidence of a causal mechanism, not just of a causal effect. Historical case studies can be better suited to detecting causal mechanisms Erik Gartzke is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, San Diego.Yonatan Lupu is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Princeton University. -

International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding

The Unintended Consequences of Democracy Promotion: International Organizations and Democratic Backsliding Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anna M. Meyerrose, M.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Alexander Thompson, Co-Advisor Irfan Nooruddin, Co-Advisor Marcus Kurtz William Minozzi Sara Watson c Copyright by Anna M. Meyerrose 2019 Abstract Since the end of the Cold War, international organizations (IOs) have engaged in unprecedented levels of democracy promotion and are widely viewed as positive forces for democracy. However, this increased emphasis on democracy has more re- cently been accompanied by rampant illiberalism and a sharp rise in cases of demo- cratic backsliding in new democracies. What explains democratic backsliding in an age of unparalleled international support for democracy? Democratic backsliding oc- curs when elected officials weaken or erode democratic institutions and results in an illiberal or diminished form of democracy, rather than autocracy. This dissertation argues that IOs commonly associated with democracy promotion can support tran- sitions to democracy but unintentionally make democratic backsliding more likely in new democracies. Specifically, I identify three interrelated mechanisms linking IOs to democratic backsliding. These organizations neglect to support democratic insti- tutions other than executives and elections; they increase relative executive power; and they limit states’ domestic policy options via requirements for membership. Lim- ited policy options stunt the development of representative institutions and make it more difficult for leaders to govern. Unable to appeal to voters based on records of effective governance or policy alternatives, executives manipulate weak institutions to maintain power, thus increasing the likelihood of backsliding. -

Islam and Democracy: Is Modernization a Barrier? John O

Religion Compass 1/1 (2007): 170±178, 10.1111/j. 1749-8171.2006.00017.x Islam and Democracy: Is Modernization a Barrier? John O. Voll Georgetown University Abstract The relationship between Islam and democracy is a hotly debated topic. Usually the disagreements are expressed in a standard form. In this form, the debaters' definitions of ªIslamº and ªdemocracyº determine the conclusions arrived at. It is possible, depending upon the definitions used, to ªproveº both positions: Islam and democracy are compatible and that they are not. To escape from the predefined conclusions, it is necessary to recognize that ªIslamº and ªdemocracyº are concepts with many definitions. In the twenty-first century, important interpretations of Islam open the way for political visions in which Islam and democracy are mutually supportive. Does religion represent an obstacle to modernization and democratization? Does religion pose a threat to democracy if a democratically elected govern- ment becomes a ªtheocracyº? Does the majority rule of democracy threaten the liberty and freedom of other members of a society? If the majority imposes its will upon minorities, is that a departure from democracy in general or form of ªliberalº democracy? Does modernization strengthen or inhibit democratization and individual liberty? These broad questions are being debated in many different contexts around the world. They provide a framework for looking at the experience of Muslim societies and the relationships between Islam and democracy. Tensions between democracy and liberty -

Theories of War and Peace

1 THEORIES OF WAR AND PEACE POLI SCI 631 Rutgers University Fall 2018 Jack S. Levy [email protected] http://fas-polisci.rutgers.edu/levy/ Office Hours: Hickman Hall #304, Tuesday after class and by appointment "War is a matter of vital importance to the State; the province of life or death; the road to survival or ruin. It is mandatory that it be thoroughly studied." Sun Tzu, The Art of War In this seminar we undertake a comprehensive review of the theoretical and empirical literature on interstate war, focusing primarily on the causes of war and the conditions of peace but giving some attention to the conduct and termination of war. We emphasize research in political science but include some coverage of work in other disciplines. We examine the leading theories, their key causal variables, the paths or mechanisms through which those variables lead to war or to peace, and the degree of empirical support for various theories. Our survey includes research utilizing a variety of methodological approaches: qualitative, quantitative, experimental, formal, and experimental. Our primary focus, however, is on the logical coherence and analytic limitations of the theories and the kinds of research designs that might be useful in testing them. The seminar is designed primarily for graduate students who want to understand – and ultimately contribute to – the theoretical and empirical literature in political science on war, peace, and security. Students with different interests and students from other departments can also benefit from the seminar and are also welcome. Ideally, members of the seminar will have some familiarity with basic issues in international relations theory, philosophy of science, research design, and statistical methods.