3515095454 Lp.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

Struggle of Titans: Book 1

From 538 BC to 231 BC, Carthage began as a dominant power along with the Etruscans and the Greeks. By 231 BC, Rome was the dominant power, and Carthage had taken major steps to conceal from the Romans, their buildup of forces in preparation to combat and overcome Rome. STRUGGLE OF TITANS: BOOK 1 by Lou Shook Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9489.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Copyright © 2017 Lou Shook ISBN: 978-1-63492-606-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida. Printed on acid-free paper. This is a work of historical fiction, based on actual persons and events. The author has taken creative liberty with many details to enhance the reader's experience. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2017 First Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE - BEGINNING OF CARTHAGE (2800-539 BC) ................. 9 CHAPTER TWO - CARTHAGE CONTINUES GROWTH (538-514 BC) ....................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER THREE - CARTHAGE SECURES WESTERN MEDITERREAN (514-510 BC) ............................................................. 32 CHAPTER FOUR - ROME REPLACES MONARCHY (510-508 BC) ...................................................................................... -

Title Page Echoes of the Salpinx: the Trumpet in Ancient Greek Culture

Title Page Echoes of the salpinx: the trumpet in ancient Greek culture. Carolyn Susan Bowyer. Royal Holloway, University of London. MPhil. 1 Declaration of Authorship I Carolyn Susan Bowyer hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Echoes of the salpinx : the trumpet in ancient Greek culture. Abstract The trumpet from the 5th century BC in ancient Greece, the salpinx, has been largely ignored in modern scholarship. My thesis begins with the origins and physical characteristics of the Greek trumpet, comparing trumpets from other ancient cultures. I then analyse the sounds made by the trumpet, and the emotions caused by these sounds, noting the growing sophistication of the language used by Greek authors. In particular, I highlight its distinctively Greek association with the human voice. I discuss the range of signals and instructions given by the trumpet on the battlefield, demonstrating a developing technical vocabulary in Greek historiography. In my final chapter, I examine the role of the trumpet in peacetime, playing its part in athletic competitions, sacrifice, ceremonies, entertainment and ritual. The thesis re-assesses and illustrates the significant and varied roles played by the trumpet in Greek culture. 3 Echoes of the salpinx : the trumpet in ancient Greek culture Title page page 1 Declaration of Authorship page 2 Abstract page 3 Table of Contents pages -

Περίληψη : Demetrius Poliorcetes (337 B.C.-283 B.C.) Was One of the Diadochi (Successors) of Alexander the Great

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Παναγοπούλου Κατερίνα Μετάφραση : Βελέντζας Γεώργιος Για παραπομπή : Παναγοπούλου Κατερίνα , "Demetrius Poliorcetes", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Κωνσταντινούπολη URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=7727> Περίληψη : Demetrius Poliorcetes (337 B.C.-283 B.C.) was one of the Diadochi (Successors) of Alexander the Great. He initially co-ruled with his father, Antigonus I Monophthalmos, in western Asia Minor and participated in campaigns to Asia and mainland Greece. After the heavy defeat and death of Monophthalmos in Ipsus (301 B.C.), he managed to increase his few dominions and ascended to the Macedonian throne (294-287 B.C.). He spent the last years of his life captured by Seleucus I in Asia Minor. Άλλα Ονόματα Poliorcetes Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης 337/336 BC – Macedonia Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου 283 BC – Asia Minor Κύρια Ιδιότητα Hellenistic king 1. Youth Son of Antigonus I Monophthalmos and (much younger) Stratonice, daughter of the notable Macedonian Corrhaeus, Demetrius I Poliorcetes was born in 337/6 B.C. in Macedonia and died in 283 B.C. in Asia Minor. His younger brother, Philip, was born in Kelainai, the capital of Phrygia Major, as Stratonice had followed her husband in the Asia Minor campaign. Demetrius spent his childhood in Kelainai and is supposed to have received mainly military education.1 At the age of seventeen he married Phila, daughter of the Macedonian general and supervisor of Macedonia, Antipater, and widow of Antipater’s expectant successor, Craterus. The marriage must have served political purposes, as Antipater had been appointed commander of the Macedonian district towards the end of the First War of the Succesors (321-320 B.C.). -

The First Solvay: 350 BC Aristotle's Assault on Plato

The First Solvay: 350 BC Aristotle’s Assault on Plato by Susan J. Kokinda May 11—If one looks at the principles embedded in stein’s relativity, Planck’s quantum. and Vernadsky’s Plato’s scientific masterwork,Timaeus , especially from noösphere. But in the immediate foreground was Philo- the vantage point of the work of Einstein and Verna- laus of Croton (in Italy), the earliest Pythagorean from dsky in the Twentieth Century, one can understand why whom any fragments survive. (Fortunately, Philolaus the oligarchy had to carry out a brutal assault on Plato himself survived the arson-murder of most of the and his Academy, an assault led by Aristotle, which ul- second generation of Pythagoreans in Croton, and relo- timately resulted in the imposition of Euclid’s mind- cated to Greece.) In the footprints of those fragments deadening geometry on the world, and the millennia- walks the Timaeus. long set-back of Western civilization. Philolaus’ fragments are like a prelude to the inves- That the oligarchical enemy of mankind responds tigations which fill theTimaeus . And so, astronomy, ge- with brute force to those philosophers and scientists, ometry, and harmony were at the core of the work of who act on the basis of human creativity, was captured Plato’s Academy. Indeed, every member was given the in the opening of Aeschylus’ great tragedy, “Prometheus assignment of developing an hypothesis to account for Bound.” On orders from Zeus, the Olympian ruler, the motions of the heavenly bodies. Kratos (might) and Bios (force) oversaw Prometheus’ And it is to Philolaus that Johannes Kepler refers, in punishment. -

Download PDF Datastream

A Dividing Sea The Adriatic World from the Fourth to the First Centuries BC By Keith Robert Fairbank, Jr. B.A. Brigham Young University, 2010 M.A. Brigham Young University, 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in Ancient History at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2018 © Copyright 2018 by Keith R. Fairbank, Jr. This dissertation by Keith R. Fairbank, Jr. is accepted in its present form by the Program in Ancient History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _______________ ____________________________________ Graham Oliver, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _______________ ____________________________________ Peter van Dommelen, Reader Date _______________ ____________________________________ Lisa Mignone, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _______________ ____________________________________ Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Keith Robert Fairbank, Jr. hails from the great states of New York and Montana. He grew up feeding cattle under the Big Sky, serving as senior class president and continuing on to Brigham Young University in Utah for his BA in Humanities and Classics (2010). Keith worked as a volunteer missionary for two years in Brazil, where he learned Portuguese (2004–2006). Keith furthered his education at Brigham Young University, earning an MA in Classics (2012). While there he developed a curriculum for accelerated first year Latin focused on competency- based learning. He matriculated at Brown University in fall 2012 in the Program in Ancient History. While at Brown, Keith published an appendix in The Landmark Caesar. He also co- directed a Mellon Graduate Student Workshop on colonial entanglements. -

Illinois Classical Studies

immmmmu NOTICE: Return or renew alt Library Materials! The Minimum Fee for each Lost Book Is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result In dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN m •' 2m MAR1 m ' 9. 2011 m nt ^AR 2 8 7002 H«ro 2002 - JUL 2 2ii^ APR . -.^ art Ll( S~tH ^ v^ a ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX 1994 ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX 1994 SCHOLARS PRESS ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XIX Studies in Honor of Mirosiav Marcovich Volume 2 The Board of Trustees University of Illinois Copies of the journal may be ordered from: Scholars Press Membership Services P.O. Box 15399 Aaanta,GA 30333-0399 Printed in the U.S.A. EDITOR David Sansone ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE William M. Calder IH J. K. Newman Eric Hostetter S. Douglas Olson Howard Jacobson Maryline G. Parca CAMERA-READY COPY PRODUCED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF MARY ELLEN FRYER Illinois Classical Studies is published annually by Scholars Press. Camera- ready copy is edited and produced in the Department of the Classics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Each contributor receives fifty offprints free of charge. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies Department of the Classics 4072 Foreign Languages Building 707 South Mathews Avenue Urbana, Illinois 61801 Miroslav Marcovich Doctor of Humane Letters, Honoris Causa The University of Illinois 15 May 1994 . -

Attic Inscriptions in UK Collections Ashmolean Museum Oxford Christopher De Lisle

Attic Inscriptions in UK Collections Ashmolean Museum Oxford Christopher de Lisle AIUK VOLUME ASHMOLEAN 11 MUSEUM 2020 AIUK Volume 11 Published 2020 AIUK is an AIO Papers series ISSN 2054-6769 (Print) ISSN 2054-6777 (Online) Attic Inscriptions in UK Collections is an open access AIUK publication, which means that all content is available without Attic Inscriptions charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the in UK Collections full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. C b n a This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence. Original copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. This paper is part of a systematic publication of all the Attic inscriptions in UK collections by Attic Inscriptions Online as part of a research project supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC): AH/P015069/1. PRINCIPAL PROJECT AIO ADVISORY INVESTIGATOR TEAM BOARD Stephen Lambert Peter Liddel Josine Blok Polly Low Peter Liddel Robert Pitt Polly Low Finlay McCourt Angelos P. Matthaiou Irene Vagionakis S. Douglas Olson P.J. Rhodes For further information see atticinscriptions.com Contents CONTENTS Contents i Preface ii Abbreviations iv 1. The Collection of Attic Inscriptions in the Ashmolean Museum xiii 2. The Inscriptions: A Decree, a Calendar of Sacrifices, and a Dedication 9 1. Proxeny Decree for Straton, King of the Sidonians 9 2. -

Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 230 August, 2012 Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD) by Lucas Christopoulos Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Bridging the Hellespont: the Successor Lysimachus - a Study

BRIDGING THE HELLESPONT: THE SUCCESSOR LYSIMACHUS - A STUDY IN EARLY HELLENISTIC KINGSHIP Helen Sarah Lund PhD University College, London ProQuest Number: 10610063 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10610063 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Literary evidence on Lysimachus reveals a series of images which may say more about contemporary or later views on kingship than about the actual man, given the intrusion of bias, conventional motifs and propaganda. Thrace was Lysimachus* legacy from Alexander's empire; though problems posed by its formidable tribes and limited resources excluded him from the Successors' wars for nearly ten years, its position, linking Europe and Asia, afforded him some influence, Lysimachus failed to conquer "all of Thrace", but his settlements there achieved enough stability to allow him thoughts of rule across the Hellespont, in Asia Minor, More ambitious and less cautious than is often thought, Lysimachus' acquisition of empire in Asia Minor, Macedon and Greece from c.315 BC to 284 BC reflects considerable military and diplomatic skills, deployed primarily when self-interest demanded rather than reflecting obligations as a permanent member of an "anti-Antigonid team". -

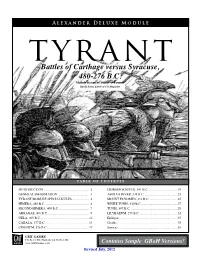

Battles of Carthage Versus Syracuse, 480-276 B.C. Module Design by Daniel A

Tyrant Alexander Deluxe Module tyrant Battles of Carthage versus Syracuse, 480-276 B.C. Module Design by Daniel A. Fournie GBoH Series Editor of C3i Magazine T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 CRIMISSOS RIVER, 341 B.C. ................................... 19 GENERAL INFORMATION ...................................... 3 ABOLUS RIVER, 338 B.C. ........................................ 23 TYRANT MODULE SPECIAL RULES..................... 3 MOUNT ECNOMUS, 311 B.C. .................................. 25 HIMERA, 480 B.C. ..................................................... 4 WHITE TUNIS, 310 B.C. ............................................ 27 SECOND HIMERA, 409 B.C. .................................... 7 TUNIS, 307 B.C. ......................................................... 29 AKRAGAS, 406 B.C. .................................................. 9 LILYBAEUM, 276 B.C. .............................................. 32 GELA, 405 B.C............................................................ 12 Epilogue ....................................................................... 35 CABALA, 377 B.C. ..................................................... 14 Credits .......................................................................... 35 CRONIUM, 376 B.C. .................................................. 17 Sources ......................................................................... 36 GMT GAMES P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com Contains Simple GBoH Versions!