The Saga of Melitta Urbancic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Challenges & Opportunities for Arctic

The Challenges & Opportunities for Arctic Microstates in Developing an Energy Sector: The Role of Human Capital and Knowledge Institutes C.C.A. Smits, R.G. Bertelsen, & J.C.S. Justinussen Like many Arctic states, Iceland and the Faroe Islands used to be the resource-based economies which Greenland is today. Remotely located in relation to the World economy, Iceland and the Faroe Islands have succeeded in developing a knowledge- based economy, also related to their energy sector. To create a knowledge-based economy a sufficient mass of human capital is of crucial importance. In forming this critical mass, higher education and knowledge institutes play a central role. The cases of the Faroe Islands and Iceland show that it is possible to create a critical mass of human capital by developing strong knowledge institutes and stimulating the exchange of knowledge. Iceland has successfully developed a knowledge-based energy sector based on hydropower over the last century. Icelanders bringing home knowledge gained via graduate education at top institutes abroad, appeared of major importance. More recently the Faroe Islands have developed human capital based on oil and gas exploration activities, while no economically viable resources have been found yet. Greenland on the other side has made some important steps in creating and strengthening strong knowledge institutes, but is still far from a full-fledged knowledge-based economy such as the one in Iceland. Are there lessons to be learned from Iceland and the Faroe Islands, and how much do historic path-dependencies matter in this context? These are questions that this article will explore. -

Eudo Citizenship Observatory

EUDO CITIZENSHIP OBSERVATORY COUNTRY REPORT: ICELAND Gudni Th. Jóhannesson, Gunnar Thór Pétursson, Thorbjörn Björnsson Revised and updated January 2013 http://eudo-citizenship.eu European University Institute, Florence Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies EUDO Citizenship Observatory Report on Iceland Gudni Th. Jóhannesson,Gunnar Thór Pétursson, Thorbjörn Björnsson Revised and updated January 2013 EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Country Report, RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2013/8 Badia Fiesolana, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy © Gudni Th. Jóhannesson,Gunnar Thór Pétursson, Thorbjörn Björnsson This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] The views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union Published in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Research for the EUDO Citizenship Observatory Country Reports has been jointly supported, at various times, by the European Commission grant agreements JLS/2007/IP/CA/009 EUCITAC and HOME/2010/EIFX/CA/1774 ACIT and by the British Academy Research Project CITMODES (both projects co-directed by the EUI and the University of Edinburgh). The financial support from these projects is gratefully acknowledged. For information about the project please visit the project website at http://eudo-citizenship.eu Iceland Gudni Th. Jóhannesson,Gunnar Thór Pétursson and Thorbjörn Björnsson 1 Introduction Historically, Iceland has been among the world’s most homogenous countries. -

Jesse Byock. “Modern Nationalism and the Medieval Sagas.” in Northern Antiquity: the Post-Medieval Reception of Edda and Saga, Ed

Jesse Byock. “Modern nationalism and the medieval sagas.” In Northern Antiquity: The Post-Medieval Reception of Edda and Saga, ed. Andrew Wawn. London: Hisarlik Press, 1994, pp. 163-187. Modern Nationalism and the Medieval Sagas Jesse L. Byock National consciousness is by no means a private affair. In most cases it is determined not only by what the group that is asserting a national identity thinks of itself but is also formed in response to the views of outsiders. External opinion has been especially impor- tant to the Scandinavians, whose largely agrarian societies lay until the late nineteenth century on the fringes of European cultural innovation. Despite the growth of industry and urbanization beginning in the early nineteenth century, Scandinavia remained stigmatized as a region of cultural backwardness until the early twentieth century. Even Denmark, one of the most advanced of the Scandinavian states, long felt the scorn of critics. Albeit with a jaundiced eve, Friedrich Engels, writing to Karl Marx from Paris in 1846, said of the Danes: I have in the most recent terrible past once again made my acquaintance with Denmark and the rest of the North. You would find it a beastly place. Better the smallest German than the greatest Dane! Such a miserable atmosphere of morality, guild-cliquishness and consciousness of social status exists nowhere else any more. The Dane thinks of Germany as a country one visits in order "to keep mistresses with whom one can squander one's wealth" (Werke 27: 71-72).1 None too enthusiastic about the Danes, Engels also had thoughts on the Icelanders, a people who, like their medieval ancestors, lived in turf houses whose thick, grassy walls melted into the landscape: The Icelander still speaks the very same language as the greasy Vikings of anno 900. -

The Icelandic Federalist Papers

The Icelandic Federalist Papers No. 16: The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles To the People of Iceland: Before examining the republican character of the new plan, it is first necessary to explain the meanings of the terms and their relevance to the standards fixed in Iceland. The term republic originates from Latin “res publica,” “the common weal, a commonwealth, state, republic,” liter- ally res publica “public interest, the state,” from res “affair, matter, thing” combined with publi- ca, feminine of publicus or “public.”1 From a constitutional perspective, a republic is a country in which the head of state’s position is not hereditary.2 The president (or other chief executive) may be elected, appointed, or nominated to exercise the head of state position. This concept is the opposite of a kingdom, in which a monarch exercises power because of filiation. Historically, the term “republic” was first used in ancient Rome and thereafter where power was not exercised by a royal family, as for example in the case of Venice. The term may refer to a system that is neither monarchical nor imperial. A republic does not necessarily mean democracy since the president may be designated through authority; there are many examples of undemocratic republics among Latin American dictatorships or in the former USSR. The founda- tions of a republic are based on a will, a desire to represent the social body. It also has a norma- tive meaning connected to a judgment of values and the possibility for people to exercise their sovereignty. Even though the idea of both democracy and constitutional government emerged in Athens, the first known city republic took shape around 506 BC in India where, for the first time, a ruler was elected. -

Birth of a Nation

Birth of a Nation Iceland is currently celebrating the centenary of its sovereignty. But, in a sense, it actually marked two independence days during the last century. T WAS 1918, A PARTICULARLY Denmark. One day after Germany occupied Denmark, the Icelandic parlia- momentous one in modern history.I The First World War came to an end, ment passed resolutions granting Iceland full powers, especially those over Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II and his family were executed by the Bolsheviks, foreign policy. Britain courted Iceland to join the Allied cause, but Iceland and an unprecedented global flu epidemic claimed the lives of more than refused to alter its neutral stand, even though it sympathized with the Allies. 20 million, more than were killed during the four years of the war. Small Fearing the Germans might try to occupy Iceland, the British invaded the wonder, then, that such events overshadowed what was happening on a then country in May of 1940. Iceland protested but acquiesced. remote island along the southern fringes of the Arctic Circle. By 1941, there were 25,000 British troops stationed in Iceland and Iceland is the youngest and least populated country in Europe and has Britain urged Iceland to agree to allow American troops to be allowed into a very brief history. The earliest settlers did not set foot on it until near the the country, thus freeing British troops to serve elsewhere. Eventually, end of the first millennium. Throughout the Viking times and days of the there were 40,000 U.S. troops in Iceland, which was about one third of the sagas and eddas the country changed hands, so to speak, many times and native population. -

Halldór Laxness - Wikipedia

People of Iceland on Iceland Postage Stamps Halldór Laxness - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halldór_Laxness Halldór Laxness Halldór Kiljan Laxness (Icelandic: [ˈhaltour ˈcʰɪljan ˈlaxsnɛs] Halldór Laxness ( listen); born Halldór Guðjónsson; 23 April 1902 – 8 February 1998) was an Icelandic writer. He won the 1955 Nobel Prize in Literature; he is the only Icelandic Nobel laureate.[2] He wrote novels, poetry, newspaper articles, essays, plays, travelogues and short stories. Major influences included August Strindberg, Sigmund Freud, Knut Hamsun, Sinclair Lewis, Upton Sinclair, Bertolt Brecht and Ernest Hemingway.[3] Contents Early years 1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s Born Halldór Guðjónsson Later years 23 April 1902 Family and legacy Reykjavík, Iceland Bibliography Died 8 February 1998 Novels (aged 95) Stories Reykjavík, Iceland Plays Poetry Nationality Icelandic Travelogues and essays Notable Nobel Prize in Memoirs awards Literature Translations 1955 Other Spouses Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir References (m. 1930–1940) External links [1] Auður Sveinsdóttir (m. 1945–1998) Early years Laxness was born in 1902 in Reykjavík. His parents moved to the Laxnes farm in nearby Mosfellssveit parish when he was three. He started to read books and write stories at an early age. He attended the technical school in Reykjavík from 1915 to 1916 and had an article published in the newspaper Morgunblaðið in 1916.[4] By the time his first novel was published (Barn náttúrunnar, 1919), Laxness had already begun his travels on the European continent.[5] 1 of 9 2019/05/19, 11:59 Halldór Laxness - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halldór_Laxness 1920s In 1922, Laxness joined the Abbaye Saint-Maurice-et-Saint-Maur in Clervaux, Luxembourg where the monks followed the rules of Saint Benedict of Nursia. -

Raedism.B.Pdf

Honorary Consuls are integral to the effectiveness of the Icelandic Foreign Service in its primary role of furthering Iceland´s interests abroad. A Group of Honorary Consuls of Iceland who participated in the second Consular Conference in Reykjavik in 1977. Ingvi S.Ingvarsson, Permanent Secretary of State with Matthías Á. Mathiesen, Minister for Foreign Affairs, on his left side, at the third Consular Conference in Iceland in 1986. The Consular Conferences are impor- tant venues for updating Honorary Consuls of Iceland about the country they are serv- ing. The next Consular Conference will be held in Iceland in September 2001. Icelanders celebrate the achievement of independence on 17June 1944. Iceland had already assumed control of its for- eign affairs following the German occu- pation of Denmark in 1940. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs was formally estab- lished in 1941 and during the Second World War Iceland established diplomat- Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill of Great Britain visited Iceland in 1941, at the height of the bat- ic relations with the other Nordic coun- tle of the North Atlantic in the Second World War. Iceland´s strategic location between North America tries and the Allies. and Europe was important during the war to secure convoys and Allied shipping from attacks by German U-boats. The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Iceland was removed from the entrance to Embassy of Iceland in Washington D.C. on independence day, 17 June 1944 by Embassy officials. From left: Þórhallur Ásgeirsson, later The tenth Summit of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, NATO, was held Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Commerce, Hendrik Sv. -

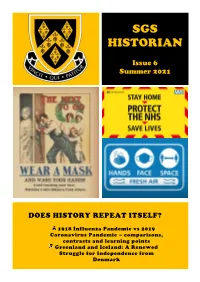

SGS Historian Issue 6, 2021

SGS HISTORIAN Issue 6 Summer 2021 DOES HISTORY REPEAT ITSELF? 1918 Influenza Pandemic vs 2019 Coronavirus Pandemic – comparisons, contrasts and learning points Greenland and Iceland: A Renewed Struggle for Independence from Denmark A note from the writing team: I have found it an incredibly rewarding experience to write an article for this magazine. It allowed me to express myself by creating an informative and interesting article in order to help educate others and bring to light lesser known aspects of history which aren’t always taught in the main syllabus at school. We felt history repeating itself was an appropriate topic to base the magazine around due to the concerningly cyclical nature of recent events such as the 1919-1920 flu pandemic vs the 2019-2020 coronavirus pandemic, the rise of far right extremism or some recent religious and racial conflicts. These all paint a worrying picture of the constant similarities to countless historical events which many people, both historical and modern, falsely believed were one time issues. Alex Ward A note from the teaching staff: Whilst this is the sixth edition of this magazine, I do think it is important to recognise that this is the second issue to be produced during the coronavirus pandemic. This is important because we should recognise the impressive additional commitment to scholarship, beyond A Level work, that is reflected in this publication. The pupils returned to in-person teaching on 8th March. Many have combined their writing with early EPQ work, the limited resumption of co-curricular activities and continuing with four A Level programmes of study. -

Icelandic Foreign Affairs 2018

MINISTRY FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ICELANDIC FOREIGN AFFAIRS 2018 Excerpt from the report by the Minister for Foreign Affairs to Parliament 2018 International cooperation: Economics, trade, defence, and politics OSCE Andorra Bosnia and Kazakhstan Monaco San Marino Ukraine Armenia Herzegovina Kyrgizstan Mongolia Serbia Uzbekistan Azerbaijan Georgia Macedonia Montenegro Tajikistan Belarus Holy See Moldova Russia Turkmenistan SCHENGEN EEA EFTA EU Liechtenstein EUROZONE OECD Australia Chile Switzerland Sweden Austria Cyprus Israel Finland Ireland Japan Malta Mexico NATO New Zealand South Korea Belgium Lithuania Canada Czech Estonia Luxembourg United Iceland Republic States France Netherlands Norway Denmark Turkey Germany Portugal Hungary Greece Slovakia Poland Italy Slovenia Latvia Spain United Kingdom Bulgaria Albania Croatia Romania Published by: Ministry for Foreign Affairs, 2018 / Photos: Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Reykjavík Museum of Photography, OSCE, UN Photo Library, NATO, Council of Europe, WTO, Wikimedia Commons, Norden.org 100 YEARS OF SOVEREIGNTY IN ICELAND 1918 - 2018 100 Years Sovereignty in Iceland / Nordic Council flag / Embassy shield of the Kingdom of Iceland, used until 1944 / Minister for Foreign Affairs with António Guterres, SG of the UN From Home Rule to Sustainable Development Goals This year we are commemo- the EEA Agreement to make an impact on new EEA rules rating the centenary of and to communicate Iceland’s views early in the process. Iceland becoming a free Significant effort is needed in this area. and sovereign nation with the passage of the Danish– I have often, both verbally and in writing, drawn attention Icelandic Act of Union to the fact that Icelanders must adapt its working methods in 1918. It was then that to changes in global trade patterns. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units V 10 - March 2020 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2020. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v10” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this venture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/ v-dem-institute/funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Capital Cities Around the World This Page Intentionally Left Blank Capital Cities Around the World

Capital Cities around the World This page intentionally left blank Capital Cities around the World An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture ROMAN ADRIAN CYBRIWSKY Copyright 2013 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian. Capital cities around the world : an encyclopedia of geography, history, and culture / Roman Adrian Cybriwsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61069-247-2 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9 (ebook) 1. Cities and towns. 2. Capitals. I. Title. G140.C93 2013 909'.09732—dc23 2012046346 ISBN: 978-1-61069-247-2 EISBN: 978-1-61069-248-9 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America Contents List of Capital Cities vii List of Capital Cities by Country xiii Preface xix Introduction xxiii Capital Cities A-Z 1 Appendix: Selected Historic Capital Cities around the World 349 Selected Bibliography 357 Index 361 This page intentionally left blank List of Capital Cities Abu