Download 1 File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

A Guide for Teaching About Adolescent Sexuality and Reproductive Health

CHRISTIAN FAMILY LIFE EDUCATION: A Guide for Teaching about Adolescent Sexuality and Reproductive Health Written by Shirley Miller for Margaret Sanger Center International © 2001 ~ This guide was written especially for Christians and others who value the importance of talking comfortably and effectively with young people and adults about issues related to healthy sexuality and reproductive health. It provides state of the art information on a variety of topics related to human sexuality, gender, adolescents, growth and development, parenting, domestic violence, STIs, HIV/AIDS, sexual abuse, substance abuse, conflict resolution, goal setting and other important life issues. ~ Margaret Sanger Center International, Copyright 2001 2 CONTENTS Page PREFACE..............................................................................................9 INTRODUCTION: Why Christian Family Life Education? .............10 Important Issues Concerning Adolescents.....................................13 PART ONE: CHRISTIAN FAMILY LIFE EDUCATION About This Guide..................................................................................16 Objectives of the Christian Family Life Education Programme............18 Characteristics of an Effective Christian Family Life Educator ...........20 Providing Support for Parents ..............................................................22 Communicating with Young People about Sex....................................23 Clarifying Values ..................................................................................25 -

Pengaruh Penyimpangan Seksual Dalam Perilaku Dan Pola Pikir Siswa Terhadap Prestasi Belajar Pada Mata Pelajaran Pendidikan Agam

PENGARUH PENYIMPANGAN SEKSUAL DALAM PERILAKU DAN POLA PIKIR SISWA TERHADAP PRESTASI BELAJAR PADA MATA PELAJARAN PENDIDIKAN AGAMA ISLAM DI SMPN 1 KAPETAKAN KABUPATEN CIREBON TESIS Diajukan sebagai Salah Satu Syarat untuk Memperoleh Gelar Magister Pendidikan Islam pada Program Studi Pendidikan Islam Konsentrasi Psikologi Pendidikan Islam Oleh: DICKY SURACHMAN NIM: 505820028 PROGRAM PASCASARJANA INSTITUT AGAMA ISLAM NEGERI SYEKH NURJATI CIREBON 2011 i PENGARUH PENYIMPANGAN SEKSUAL DALAM PERILAKU DAN POLA PIKIR SISWA TERHADAP PRESTASI BELAJAR PADA MATA PELAJARAN PENDIDIKAN AGAMA ISLAM DI SMPN 1 KAPETAKAN KABUPATEN CIREBON Disusun oleh : DICKY SURACHMAN NIM : 505820028 Telah diujikan pada tanggal 21 Juni 2011 dan dinyatakan memenuhi syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Magister Pendidikan Islam (M.Pd.I) Cirebon, 21 Juni 2011 Dewan Penguji Ketua/Anggota, Sekretaris/Anggota, Prof. Dr. H. Jamali Sahrodi, M.Ag Dr. H. Ahmad Asmuni, MA Pembimbing 1/Penguji 2, Pembimbing 2/Penguji 3, Prof. Dr. H. Jamali Sahrodi, M.Ag Dr. Septi Gumiandari, M.Ag Penguji 1, Dr. A.R. Idham Kholid, M.Ag Direktur, Prof. Dr. H. Jamali Sahrodi, M.Ag NIP. 19680408 199403 1 003 i PERNYATAAN KEASLIAN . Yang bertanda Tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Dicky Surachman NIM : 505820028 Program Studi : Pendidikan Islam Konsentrasi : Psikologi Pendidikan Islam Program Pascasarjana Institut Agama Islam Negeri Syekh Nurjati Cirebon menyatakan bahwa TESIS ini secara keseluruhan adalah ASLI hasil penelitian saya, kecuali pada bagian-bagian yang dirujuk sumbernya dan disebutkan dalam daftar pustaka. Pernyataan ini dibuat dengan sejujurnya dan dengan penuh kesungguhan hati, disertai kesiapan untuk menanggung segala resiko yang mungkin diberikan, sesuai dengan peraturan yang berlaku. apabila di kemudian hari ditemukan adanya pelanggaran terhadap etika keilmuan atau ada klaim terhadap keaslian karya saya ini. -

Preparing Care Provid in Adolescent Sexual an Reproductive Health

Youth.now PREPARING CARE PROVID IN ADOLESCENT SEXUAL AN REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH A Resource Guide forTrainers, Educators and Facilitators 4> 0 The Futures Group International GOJ / USAID JAMAICA ADOLESCENT SEXUAL & REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH TRAINER RESOURCE BOOK (TRB) The Jamaica Adolescent Reproductive Health Activity (Youth.now) is a five-year project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Jamaica Mission under contract # 532-c-00-00-00003-00. Youth.now is implemented on behalf of the Ministry of Health (Jamaica) by the Futures Group International in collaboration with Margaret Sanger Centre International (MSCI) and Dunlop Corbin Communications (DCC). 2-4 KING STREET KINGSTON JAMAICA 2002. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This manual and resource guide was developed over the span of two years. In that time, many individuals and organizations contributed their time and expertise to their development. We would like to thank the educators, child development specialists, representatives from health care agencies that serve adolescents, and curriculum development specialists who participated in the Curriculum Development Workshop and provided valuable insights and experiences to the process. The individuals representing the Ministry of Education (Dr. Delores Brissett), University of the West Indies (Mrs. L. Williams), West Indies School of Public Health (Ms. Ivy Limonius), Heart Trust NTA (Ms. Clover Barnett, Ms. Jacqueline Phinn, Ms. Carmen Brown), Red Cross Society of Jamaica (Ms. Lois Hue), Jamaica Association for the Deaf (Ms. Shirley Reid, Ms. Karen Bailey), Ministry of Health (Mrs. Lola Ramocan), USAID (Ms. Sheila Lutjens, Ms. Jennifer King-Johnson), and the Futures Group International (Ms. Cate Lane, Ms. Mary Beckles, Mr. Hilton Grace) participated in conceptualizing the manual and its content. -

Paraphilias Among Gay Men in Puerto Rico

PARAPHILIAS AMONG GAY MEN IN PUERTO RICO A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The American Academy of Clinical Sexologists In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clinical Sexology By Edward H. Fankhanel, M.A., Ed.D. Orlando, Florida October 2008 Abstract This study was design to gather basic descriptive data about paraphilic behaviors among gay men in Puerto Rico and the relationship of such behaviors with their mental and emotional state. Participants (N = 429) were recruited by availability at gay men socializing venues and events across the entire island of Puerto Rico. As such, results cannot be generalized to the entire gay men population of Puerto Rico. The results reflect that, the DSM-IV-TR paraphilias most reported by the participants were Voyeurism and Exhibitionism. The most reported less-common sexual fantasies, desires and/or behaviors were observing erotic pictures and partialism. Other DSM-IV-TR specific paraphilias, along with sexual fantasies, desires, and/or behaviors that could be considered under Paraphilias NOS were also reported by some participants. However, the design of the study does not allow differentiating between participants that only fantasized such paraphilias, versus those that have sexual desires and/or act out such behaviors. Over 90% of the participants reported good self esteem and stable mental and emotional health at the time of the study. Additionally, two-thirds of the participants aver feeling good during the experience of a less common sexual fantasy, desire, and/or behavior; feeling that remains, for the most part, after such fantasies, desires, and/or behaviors have culminated. -

Aptitudes and Attitudes Among Licensed Professional Counselors Regarding

Aptitudes and Attitudes among Licensed Professional Counselors Regarding Human Sexuality and Sexual Counseling in Puerto Rico: An Exploratory Study A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The American Academy of Clinical Sexologists In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clinical Sexology By Orlando García Colón, MPH, MFC, LPC Orlando, Florida May 2017 I © Copyright by Orlando García Colón, MPH, MFC, LPC. 2017 All Rights Reserved II III Abstract The purpose of this study was to explore the aptitude and attitude exhibited by a group of Licensed Professional Counselors in Puerto Rico regarding human sexuality and sex counseling. Descriptive data was gathered by a self-administrated questionnaire. Out of the 100 counselors that were invited to participate, 64 accepted the invitation. The sample group (N=64) was recruited according to their availability. Due to the size of the sample the results do not reflect the reality of all professional counselors in Puerto Rico. The participants were asked to answered basic socio-demographic questions. Almost half of the sample group was composed by Guidance Counselors. Majority of the participants were women with more than 15 years of experience in the field and who worked in the public education system. The level of knowledge was measured by two factors; previous education on sexuality and by the results obtained on a self-evaluation exercise using a Likert scale. The instrument included 22 basic concepts related to sexuality. More than half of the respondents (56%) answered they had taken a course on human sexuality. The present results indicated that 49% of the sample considered that they had a high or very high level of knowledge concerning human sexuality. -

Nuisance Sex Behaviors ❖ ❖ ❖

04-Holmes-45515.qxd 5/28/2008 3:12 PM Page 63 4 Nuisance Sex Behaviors ❖ ❖ ❖ There are many sexual behaviors that are completely abhorrent to the senses of most Americans. These practices become more visible as scores of sex offenders are placed in correctional institutions through- out the United States. Sex offenders in prisons currently number more than 234,000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2004). The preponderance of those offenders are involved in rape and other violent sex crimes. However, there is a growing amount Erotolalia of serious literature that suggests that Deriving major sexual satisfaction from many rapists, lust murderers, and sexu- talking about or listening to talk about sex ally motivated serial murderers have Erotomania histories of sexual behavior that reflect A compulsive interest in sexual matters patterns that in the past have been con- sidered only nuisances—not behaviors to become seriously concerned about (Holmes & Holmes, 2001; Masters & Robertson, 1990; McCarthy, 1984). Rosenfield (1985), for example, found that 62% of sex offenders in a prison sample revealed deviant sexual acts other than those for which they were sent to prison. This position will be reinforced by other stud- ies we will cite later in this chapter. They admitted to sex acts such as incest, frottage, voyeurism, and bestiality. Sexual acts that cause no obvious physical harm to the practitioner or the victim we term nuisance sex behaviors. This chapter is devoted to discussion of these activities. 63 04-Holmes-45515.qxd 5/28/2008 3:12 PM Page 64 64 SEX CRIMES Nuisance sex behaviors are often viewed in a less serious fashion than sex crimes that cause serious trauma and death. -

Pathfinder Vices

Pathfinder Vices A note on abbreviations: BUCK is the Book of Unlawful Carnal Knowledge, BoEF is the Book of Erotic Fantasy, EAN is the Encyclopedia of Arcane Nymphology, and QT is Quintessential Temptress. A note on bonuses: cup size sometimes grants a bonus to influence breast fetishists with Diplomacy. This bonus does not stack with itself even if multiple instances of it exist on the same character. The largest bonus (usually +2) applies Sex Cup Size The character’s class and possibly their race may have an effect on cup size. The steps are as follows: AA,A,B,C,D,DD(E),DDD(F), G,GG, GGG, and finally, HELLO! *. At the GM’s option, Characters with DDD or larger breasts must pay double for clothing or suffer from nearly constant button pops or other wardrobe malfunctions, due to lack of clothing size standardization in the era. Optional Rule: Weight Increases- Breasts are heavy. Who hasn’t heard complaints from some woman about having 5 pounds worth of milk sack attached to her chest? This optional rule reflects that, with a few caveats: 1) weight increase is given as a percentage due to races of different sizes having different cup size parameters 2) being three dimensional objects, breast weight increases are not linear, and finally 3) I’ve done extremely complicated math for other supplements that doesn’t have a place here due to the implementation of an easier system. The table below is an approximation of that math: Cup Size Weight Increase D 5% DD 7% DDD 9% G 12% GG 15% GGG 20% HELLO! 25% Default cup sizes for classes are determined by their Hit Dice (more rugged characters are generally thicker) and Saves D12 Hit Dice: D cup D10 Hit Dice: C cup D8 Hit Dice: B cup D6 Hit Dice: A cup * Originally every cup past A had double and triple letter steps. -

A Narrative Study of Compulsive Sexual Behaviour in Men by F

A Narrative Study of Compulsive Sexual Behaviour in Men by F. Patrick Burr B.Sc, Spring Hill College, 1970 M.Sc, University of Minnesota, 1980 A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Graduate Studies (The department of Counselling Psychology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard e University of British Columbia June 1998 © F. Patrick Burr, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) ii ABSTRACT Considerable attention has been given to the subject of Compulsive Sexual Behaviour (CSB) by public and academic interests in the last five years. Much of this attention is highly negative. However, CSB as a personal and societal problem is widespread in western culture. It can be broadly linked to family violence, societal sexism, and to major criminal activity. This study identifies the lived realities of three men which are key to their recovery from various manifestations of compulsive sexual behaviours. The participants are all from local twelve step programs oriented towards healing from CSB. -

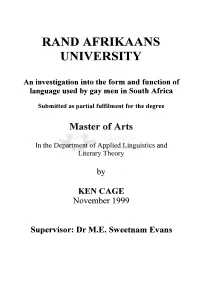

An Investigation Into the Form and Function of Language Used by Gay Men in South Africa

RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY An investigation into the form and function of language used by gay men in South Africa Submitted as partial fulfilment for the degree Master of Arts In the Department of Applied Linguistics and Literary Theory by KEN CAGE November 1999 Supervisor: Dr M.E. Sweetnam Evans ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the following persons for their contributions to this study: My supervisor, Dr Moyra Sweetnam Evans, for enthusiastic support and constructive guidance; The members of staff of the Department of Applied Linguistics and Literary Theory at the Rand Afrikaans University for their consistent support and interest; The staff of the Inter-Library Loans Department in the R.A.U. Library for excellent and friendly service in sourcing the many books and articles which I required; My mother, Patricia Cage, for proofreading much of this study; My life-partner, Deon Hendrikz, for his understanding, interest and support; The many gay men and women who participated in the gathering of data and who gave me encouragement in my research. CONTENTS Chapter 1 1.1. Background 1 1.2. Terminology 4 1.2.1. The meaning of the word 'gay' 4 1.2.2. The meaning of the word 'subculture' 7 1.3. Why study gay 'language'? 7 1.4. Handling of sensitive material 10 1.5. Gayle as an element of 'Camp' 10 1.6. Origins of the gay subculture in South Africa 12 1.7. Reasons for this study 13 1.8. Personal Experience 13 1.9. The Parameters of the Research 13 1.10. Presuppositions 14 1.11. -

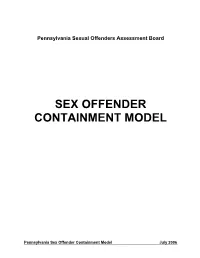

Sex Offender Containment Model

Pennsylvania Sexual Offenders Assessment Board SEX OFFENDER CONTAINMENT MODEL Pennsylvania Sex Offender Containment Model July 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click section and you will be directed to the corresponding page) CHAPTER 1 — INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................1 Impetus to This Model ................................................................................................................ 2 SOMT – Key Findings and Recommendations ........................................................................4 Newly Enacted Federal Legislation...........................................................................................5 Recommendations...................................................................................................................... 5 Pre-Incarceration: Investigations, Assessments and Sentencing............................................................. 5 Appendix: Grant Collaborative Team......................................................................................11 Addendum – September 2006..................................................................................................13 CHAPTER 2 — PENNSYLVANIA STATUTES............................................................................1 Overview ......................................................................................................................................2 Sentencing in Pennsylvania ..................................................................................................................... -

University of Minnesota

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Twin Cities Campus Department of Psychiatry F282/2A West Medical School 2450 Riverside Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55454 Office: 612-273-9800 June 1, 2013 Don Feeney Minnesota State Lottery Dear Don, it is a great pleasure to provide this letter to support the nomination of Mark Griffiths for the NCPG's Lifetime Achievement. Mark’s productive research career and his prominent role as a long-standing leader in the field easily make him worthy of NCPG’s lifetime award. Sincerely, Ken C. Winters, Ph.D. Professor [email protected] 1 May 16, 2013 Awards Committee International Journal National Council on Problem Gambling of Mental Health and Washington, D.C. Addiction Subject: Nomination of Professor Mark Griffiths, Ph.D. for the NCPG Lifetime Research Award I am honored to nominate Professor Mark Griffiths, Ph.D. for the NCPG Lifetime Research Award. Professor Griffiths is with no doubt one of the leading researchers in the field of gambling. With hundreds of peer- reviewed articles, reports, and book chapters under his belt, Professor Griffiths is the youngest professor/reader ever appointed at Nottingham Trent University. To honor his extra-ordinary achievements, we have dedicated an entire issue (2007) to Professor Griffiths. Editor-in-Chief: Masood Zangeneh ISSN: 1557-1874 (print version) Professor Griffiths has served on countless local, national and Journal no. 11469 international committees and editorial board (including our journal’s Springer New York editorial board), and has been the recipient of numerous prestigious awards. His writings have appeared in countless peer reviewed journals and magazines. Professor Griffiths has immensely contributed to growth of gambling research on several fronts (theory, treatment and policy) worldwide.