Study on Integrated Circuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transistor Circuit Guidebook Byron Wels TAB BOOKSBLUE RIDGE SUMMIT, PA

TAB BOOKS No. 470 34.95 By Byron Wels TransistorCircuit GuidebookByronWels TABBLUE RIDGE BOOKS SUMMIT,PA. 17214 Preface beforemeIa supposepioneer (along the my withintransistor firstthe many field.experiencewith wasother Weknown. World were using WarUnlike solid-stateIIsolid-state GIs) today's asdevices somewhat experimen- receivers marks of FIRST EDITION devicester,ownFirst, withsemiconductors! youwith a choice swipedwhichor tank. ofto a sealed,Here'sexperiment, pairThen ofhow encapsulated, you earphones we carefullywe did had it: from totookand construct the veryonenearest exoticof our the THIRDSECONDFIRST PRINTING-SEPTEMBER PRINTING-AUGUST PRINTING-JANUARY 1972 1970 1968 plane,wasyouAnphonesantenna. emptywound strung jeep,apart After toiletfull outand ofclippingas paper wire,unwoundhigh closelyrollandthe servedascatchthe far spaced.wire offas as itfrom a thewouldsafetyThe thecoil remaining-pin,magnetreach-for form, you inside.which stuckwire the Copyright © 1968by TAB BOOKS coatedNext,it into youneeded,a hunkribbons of -ofwooda razor -steel, soblade.the but point Oh,aItblued was noneprojected placedblade of the -quenchat so fancy right the pointplastic-bluedangles.of -, Reproduction or publicationPrinted inof the ofAmerica the United content States in any manner, with- themindfoundphoneground pin you,the was couldserved right not wired contact lacquerspotas toa onground blade, it. theblued.blade'sAconnector, pin,bayonet bluing,and stuck antennaand you hilt thecould coil.-deep other actuallyIfin ear- youthe isoutherein. assumed express -

Electronic Circuit Design and Component Selecjon

Electronic circuit design and component selec2on Nan-Wei Gong MIT Media Lab MAS.S63: Design for DIY Manufacturing Goal for today’s lecture • How to pick up components for your project • Rule of thumb for PCB design • SuggesMons for PCB layout and manufacturing • Soldering and de-soldering basics • Small - medium quanMty electronics project producMon • Homework : Design a PCB for your project with a BOM (bill of materials) and esMmate the cost for making 10 | 50 |100 (PCB manufacturing + assembly + components) Design Process Component Test Circuit Selec2on PCB Design Component PCB Placement Manufacturing Design Process Module Test Circuit Selec2on PCB Design Component PCB Placement Manufacturing Design Process • Test circuit – bread boarding/ buy development tools (breakout boards) / simulaon • Component Selecon– spec / size / availability (inventory! Need 10% more parts for pick and place machine) • PCB Design– power/ground, signal traces, trace width, test points / extra via, pads / mount holes, big before small • PCB Manufacturing – price-Mme trade-off/ • Place Components – first step (check power/ground) -- work flow Test Circuit Construc2on Breadboard + through hole components + Breakout boards Breakout boards, surcoards + hookup wires Surcoard : surface-mount to through hole Dual in-line (DIP) packaging hap://www.beldynsys.com/cc521.htm Source : hap://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Breadboard_counter.jpg Development Boards – good reference for circuit design and component selec2on SomeMmes, it can be cheaper to pair your design with a development -

Integrated Circuits

CHAPTER67 Learning Objectives ➣ What is an Integrated Circuit ? ➣ Advantages of ICs INTEGRATED ➣ Drawbacks of ICs ➣ Scale of Integration CIRCUITS ➣ Classification of ICs by Structure ➣ Comparison between Different ICs ➣ Classification of ICs by Function ➣ Linear Integrated Circuits (LICs) ➣ Manufacturer’s Designation of LICs ➣ Digital Integrated Circuits ➣ IC Terminology ➣ Semiconductors Used in Fabrication of ICs and Devices ➣ How ICs are Made? ➣ Material Preparation ➣ Crystal Growing and Wafer Preparation ➣ Wafer Fabrication ➣ Oxidation ➣ Etching ➣ Diffusion ➣ Ion Implantation ➣ Photomask Generation ➣ Photolithography ➣ Epitaxy Jack Kilby would justly be considered one of ➣ Metallization and Intercon- the greatest electrical engineers of all time nections for one invention; the monolithic integrated ➣ Testing, Bonding and circuit, or microchip. He went on to develop Packaging the first industrial, commercial and military ➣ Semiconductor Devices and applications for this integrated circuits- Integrated Circuit Formation including the first pocket calculator ➣ Popular Applications of ICs (pocketronic) and computer that used them 2472 Electrical Technology 67.1. Introduction Electronic circuitry has undergone tremendous changes since the invention of a triode by Lee De Forest in 1907. In those days, the active components (like triode) and passive components (like resistors, inductors and capacitors etc.) of the circuits were separate and distinct units connected by soldered leads. With the invention of the transistor in 1948 by W.H. Brattain and I. Bardeen, the electronic circuits became considerably reduced in size. It was due to the fact that a transistor was not only cheaper, more reliable and less power consuming but was also much smaller in size than an electron tube. To take advantage of small transistor size, the passive components too were greatly reduced in size thereby making the entire circuit very small. -

35402 Electronic Circuit R TG

Electricity and Electronics Electronic Circuit Repair Introduction The purpose of this video is to help you quickly learn the most common methods used to trou- bleshoot electronic circuits. Electronic troubleshooting skills are needed to diagnose and repair several types of devices. These devices include stereos, cameras, VCRs, and much more. As mentioned, the program will explain how to diagnose and repair different types of electronic com- ponents and circuits. Viewers will also learn how to use the specialized tools and instruments needed to test these particular types of circuits and components. If students plan to enter any type of electronics field, viewing this program will prove to be beneficial. The program is organized into major sections or topics. Each section covers one major segment of the subject. Graphic breaks are given between each section so that you can stop the video for class discussion, demonstrations, to answer questions, or to ask questions. This allows you to watch only a portion of the program each day, or to present it in its entirety. This program is part of the ten-part series Electricity and Electronics, which includes the following titles: • Electrical Principles • Electrical Circuits: Ohm's Law • Electrical Components Part I: Resistors/Batteries/Switches • Electrical Components Part II: Capacitors/Fuses/Flashers/Coils • Electrical Components Part III: Transformers/Relays/Motors • Electronic Components Part I: Semiconductors/Transistors/Diodes • Electronic Components Part II: Operation—Transistors/Diodes • Electronic Components Part III: Thyristors/Piezo Crystals/Solar Cells/Fiber Optics • Electrical Troubleshooting • Electronic Circuit Repair To order additional titles please see Additional Resources at www.filmsmediagroup.com at the end of this guide. -

Capacitors and Inductors

DC Principles Study Unit Capacitors and Inductors By Robert Cecci In this text, you’ll learn about how capacitors and inductors operate in DC circuits. As an industrial electrician or elec- tronics technician, you’ll be likely to encounter capacitors and inductors in your everyday work. Capacitors and induc- tors are used in many types of industrial power supplies, Preview Preview motor drive systems, and on most industrial electronics printed circuit boards. When you complete this study unit, you’ll be able to • Explain how a capacitor holds a charge • Describe common types of capacitors • Identify capacitor ratings • Calculate the total capacitance of a circuit containing capacitors connected in series or in parallel • Calculate the time constant of a resistance-capacitance (RC) circuit • Explain how inductors are constructed and describe their rating system • Describe how an inductor can regulate the flow of cur- rent in a DC circuit • Calculate the total inductance of a circuit containing inductors connected in series or parallel • Calculate the time constant of a resistance-inductance (RL) circuit Electronics Workbench is a registered trademark, property of Interactive Image Technologies Ltd. and used with permission. You’ll see the symbol shown above at several locations throughout this study unit. This symbol is the logo of Electronics Workbench, a computer-simulated electronics laboratory. The appearance of this symbol in the text mar- gin signals that there’s an Electronics Workbench lab experiment associated with that section of the text. If your program includes Elec tronics Workbench as a part of your iii learning experience, you’ll receive an experiment lab book that describes your Electronics Workbench assignments. -

An Integrated Semiconductor Device Enabling Non-Optical Genome Sequencing

ARTICLE doi:10.1038/nature10242 An integrated semiconductor device enabling non-optical genome sequencing Jonathan M. Rothberg1, Wolfgang Hinz1, Todd M. Rearick1, Jonathan Schultz1, William Mileski1, Mel Davey1, John H. Leamon1, Kim Johnson1, Mark J. Milgrew1, Matthew Edwards1, Jeremy Hoon1, Jan F. Simons1, David Marran1, Jason W. Myers1, John F. Davidson1, Annika Branting1, John R. Nobile1, Bernard P. Puc1, David Light1, Travis A. Clark1, Martin Huber1, Jeffrey T. Branciforte1, Isaac B. Stoner1, Simon E. Cawley1, Michael Lyons1, Yutao Fu1, Nils Homer1, Marina Sedova1, Xin Miao1, Brian Reed1, Jeffrey Sabina1, Erika Feierstein1, Michelle Schorn1, Mohammad Alanjary1, Eileen Dimalanta1, Devin Dressman1, Rachel Kasinskas1, Tanya Sokolsky1, Jacqueline A. Fidanza1, Eugeni Namsaraev1, Kevin J. McKernan1, Alan Williams1, G. Thomas Roth1 & James Bustillo1 The seminal importance of DNA sequencing to the life sciences, biotechnology and medicine has driven the search for more scalable and lower-cost solutions. Here we describe a DNA sequencing technology in which scalable, low-cost semiconductor manufacturing techniques are used to make an integrated circuit able to directly perform non-optical DNA sequencing of genomes. Sequence data are obtained by directly sensing the ions produced by template-directed DNA polymerase synthesis using all-natural nucleotides on this massively parallel semiconductor-sensing device or ion chip. The ion chip contains ion-sensitive, field-effect transistor-based sensors in perfect register with 1.2 million wells, which provide confinement and allow parallel, simultaneous detection of independent sequencing reactions. Use of the most widely used technology for constructing integrated circuits, the complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) process, allows for low-cost, large-scale production and scaling of the device to higher densities and larger array sizes. -

Vlsi Design Lecture Notes B.Tech (Iv Year – I Sem) (2018-19)

VLSI DESIGN LECTURE NOTES B.TECH (IV YEAR – I SEM) (2018-19) Prepared by Dr. V.M. Senthilkumar, Professor/ECE & Ms.M.Anusha, AP/ECE Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Recognized under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC ACT 1956 (Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India Unit -1 IC Technologies, MOS & Bi CMOS Circuits Unit -1 IC Technologies, MOS & Bi CMOS Circuits UNIT-I IC Technologies Introduction Basic Electrical Properties of MOS and BiCMOS Circuits MOS I - V relationships DS DS PMOS MOS transistor Threshold Voltage - VT figure of NMOS merit-ω0 Transconductance-g , g ; CMOS m ds Pass transistor & NMOS Inverter, Various BiCMOS pull ups, CMOS Inverter Technologies analysis and design Bi-CMOS Inverters Unit -1 IC Technologies, MOS & Bi CMOS Circuits INTRODUCTION TO IC TECHNOLOGY The development of electronics endless with invention of vaccum tubes and associated electronic circuits. This activity termed as vaccum tube electronics, afterward the evolution of solid state devices and consequent development of integrated circuits are responsible for the present status of communication, computing and instrumentation. • The first vaccum tube diode was invented by john ambrase Fleming in 1904. • The vaccum triode was invented by lee de forest in 1906. Early developments of the Integrated Circuit (IC) go back to 1949. German engineer Werner Jacobi filed a patent for an IC like semiconductor amplifying device showing five transistors on a common substrate in a 2-stage amplifier arrangement. -

United States Patent (19) 11

United States Patent (19) 11. Patent Number: 4,503,479 Otsuka et al. 45 Date of Patent: Mar. 5, 1985 54 ELECTRONIC CIRCUIT FOR VEHICLES, 4,244,050 1/1981 Weber et al. .............. 364/431.11 X HAVING A FAIL SAFE FUNCTION FOR 4,245,150 1/1981 Driscoll et al. ................... 361/92 X ABNORMALITY IN SUPPLY VOLTAGE 4,306,270 12/1981 Miller et al. ...... ... 361/90 X 4,327,397 4/1982 McCleery ............................. 361/90 75) Inventors: Kazuo Otsuka, Higashikurume; Shin 4,348,727 9/1982 Kobayashi et al.............. 123/480 X Narasaka, Yono; Shumpei Hasegawa, Niiza, all of Japan OTHER PUBLICATIONS 73 Assignee: Honda Motor Co., Ltd., Tokyo, #18414, Res. Disclosure, Great Britain, No. 184, Aug. Japan 1979. Electronic Design; "Simple Circuit Checks Power-S- 21 Appl. No.: 528,236 upply Faults'; Lindberg, pp. 57-63, Aug. 2, 1980. (22 Filed: Aug. 31, 1983 Primary Examiner-Reinhard J. Eisenzopf Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Arthur L. Lessler Related U.S. Application Data (57) ABSTRACT 63 Continuation of Ser. No. 297,998, Aug. 31, 1981, aban doned. An electronic circuit for use in a vehicle equipped with an internal combustion engine. The electronic circuit (30) Foreign Application Priority Data comprises a constant-voltage regulated power-supply Sep. 4, 1980 (JP) Japan ................................ 55.122594 circuit, a control circuit having a central processing unit 51) Int. Cl. ......................... H02H 3/20; HO2H 3/24 for controlling electrical apparatus installed in the vehi 52 U.S. Cl. ...................................... 361/90; 123/480; cle, and a detecting circuit for detecting variations in 340/661; 364/431.11 supply voltage supplied from the power-supply circuit. -

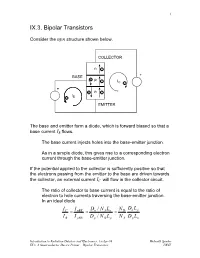

IX.3. a Semiconductor Device Primer – Bipolar Transistors LBNL 2

1 IX.3. Bipolar Transistors Consider the npn structure shown below. COLLECTOR n- BASE + +p -IC- + +n- I -B EMITTER The base and emitter form a diode, which is forward biased so that a base current IB flows. The base current injects holes into the base-emitter junction. As in a simple diode, this gives rise to a corresponding electron current through the base-emitter junction. If the potential applied to the collector is sufficiently positive so that the electrons passing from the emitter to the base are driven towards the collector, an external current IC will flow in the collector circuit. The ratio of collector to base current is equal to the ratio of electron to hole currents traversing the base-emitter junction. In an ideal diode IC I nBE Dn / N ALn N D Dn Lp = = = I B I pBE Dp / N D Lp N A Dp Ln Introduction to Radiation Detctors and Electronics, 13-Apr-99 Helmuth Spieler IX.3. A Semiconductor Device Primer – Bipolar Transistors LBNL 2 If the ratio of doping concentrations in the emitter and base regions ND /NA is sufficiently large, the collector current will be greater than the base current. ⇒ DC current gain Furthermore, we expect the collector current to saturate when the collector voltage becomes large enough to capture all of the minority carrier electrons injected into the base. Since the current inside the transistor comprises both electrons and holes, the device is called a bipolar transistor. Dimensions and doping levels of a modern high-frequency transistor (5 – 10 GHz bandwidth) 0 0.5 1.0 1.5 Distance [µm] (adapted from Sze) Introduction to Radiation Detctors and Electronics, 13-Apr-99 Helmuth Spieler IX.3. -

Laboratory Exercise 2 DC Characteristics of Bipolar Junction

DEPARTMENT OF SEMICONDUCTOR AND OPTOELECTRONIC DEVICES Semiconductor Device Laboratory Laboratory Exercise 2 DC characteristics of Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJT) The aim of the exercise The main aim of this laboratory exercise is to understand principles of operation of Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJT). It covers the measurements of static and small signal parameters. Backgrounds Physical structure of the BJT BJT is a semiconductor device having a three-layer structure with three external electrodes, the emitter (E), the base (B), and the collector (C). As shown in Fig. 1, the structure may be p-n-p or n-p-n type. Despite of the transistor type the emitter layer has always more acceptor or donor impurities added than the base or the collector layer. This asymmetry results from different roles the emitter and the collector layers play in the BJT. In normal operation of the BJT (as an amplifier), the base-emitter junction is forward biased and the base-collector junction is reverse biased. Transistor amplification is controlled by changing the current flow through the base-emitter junction. C N C . C P C . P B. N B. B . B . E . N . E P . E E (a) (b) Fig. 1. The n-p-n BJT (a) and the p-n-p BJT (b) along with their symbols There are three operating configurations of the BJT. These are the common-emitter (OE) configuration, the common-base configuration (OB), and the common-collector (OC) configuration. These configurations are shown in Fig. 2. (a) (b) (c) Fig. 2 The n-p-n transistor operating configurations: (a) common-emitter, (b) common-base, (c) common-collector DC characteristics Four types of characteristics can be defined for each of the transistor operating configurations. -

Field Effect Transistor (FET) Types and Features

Field Effect Transistor (FET) Types and Features Here I’m discussing about the topic FET. FET is another semiconductor device like BJT which can be used as switch, amplifier, resistor etc. FET consists of 3 terminals. Drain(D) Source(S) Gate(G) In these 3 terminals, Gate terminal acts as a controlling terminal. We know that a BJT acts as a current controlling device. Like that, FET also acts as a voltage controlling device. Here, the voltage between gate and source controls the drain current. So, it is called as voltage controlled device. FET Features: FET is more temperature stable compared to BJT It requires less space compared to BJT. So it is used heavily in circuits. FET has higher input impedance. So, it is more useful in amplifiers. Types of FETs: 1. Junction FET 2. MESFET 3. MOSFET Here I am discussing about the topic JFET. Junction FET (JFET): Basically the JFET is classified into 2 types. N-Channel JFET P-Channel JFET N-Channel JFET: When we consider a silicon bar and fabricated n-type at its two ends and heavily doped p-type materials at each side of the bar, the thin region will be remained as observed in figure is channel. Since this channel is in n-type bar this is called as n-channel FET. Here the current is carried by electrons. P-Channel FET: When we consider a silicon bar and fabricated p-type at its two ends and heavily doped n-type materials at each side of the bar, here the thin region remained as observed in figure is channel. -

Csd25301w1015

P-Channel CICLON NexFET™ Power MOSFETs CSD25301W1015 Features Product Summary D D • Ultra Low Qg & Qgd VDS -20 V Q 2.0 nC • Small Footprint g S S Qgd 0.32 nC • Low Profile 0.65mm height VGS= -1.5V 175 mΩ • Pb Free S G RDS(on) VGS=-2.5V 80 mΩ VGS=-4.5V 62 mΩ RoHS Compliant • CSP 1.0 x 1.5 mm Wafer Vth -0.75 V • Halogen Free Level Package Top View o Maximum Values (TA=25 C unless otherwise stated) Symbol Parameter Value Units VDS Drain to Source Voltage -20 V VGS Gate to Source Voltage ±8 V 1 ID Continuous Drain Current, TJ = 25°C -2.2 A IDM Pulsed Drain Current, TJ = 25°C1,2 -8.8 A 1 PD Power Dissipation 1.5 W TJ, TSTG Operating Junction and Storage Temperature Range -55 to 150 °C 0 1. RthJA = 85 C/W on max Cu (2 oz.) on 0.060” thick FR4 PCB 2. Pulse width ≤300 µs, duty cycle ≤ 2% RDS(ON) vs. VGS Gate Charge 300 6 ID = -1A V DS = -10V ) 250 5 ID = -1A Ω T = 125ºC 200 J 4 TJ = 25ºC 150 3 100 (V) Voltage - Gate 2 - On Resistance (m GS -V DS(on) 50 R 1 0 0 0123456 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 1.25 1.5 1.75 2 2.25 2.5 -V - Gate to Source Voltage (V) Qg - Gate Charge (nC) GS Ordering Information Type Package Package Media Qty Ship CSD25301W1015 1.0 X 1.5 Wafer Level Package 7 inch reel 3000 Tape and Reel © 2008 CICLON Semiconductor Device Corp., rev 2.3 www.ciclonsemi.com All rights reserved.