• Last Gasp: a Special Section of the Fresno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

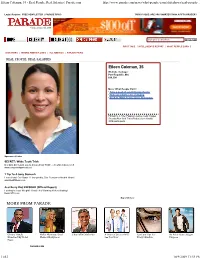

Eileen Coleman, 35 - Real People, Real Salaries | Parade.Com

Eileen Coleman, 35 - Real People, Real Salaries | Parade.com http://www.parade.com/news/what-people-earn/slideshows/real-people-... Login | Register | FREE NEWSLETTER | PARADE PICKS TODAY'S QUIZ: ARE YOU SMARTER THAN A FIFTH GRADER? Friday, October 09, 2009 Start your search here... FIRST TAKE | INTELLIGENCE REPORT | WHAT PEOPLE EARN | DICTATORS | WHERE AMERICA LIVES | ALL AMERICA | PARADE PICKS REAL PEOPLE, REAL SALARIES Eileen Coleman, 35 Website manager Port Republic, Md. $86,300 More 'What People Earn': • Take a peek at celebrity paychecks • How our salaries are changing • Back to 'What People Earn' homepage Photos by J. Tyler Pappas Creative; Getty Images; Stravato/New York Times/Redux (John Arnold); WPE participants Sponsored Links SECRET: White Teeth Trick Dentists don't want you to know about THIS teeth whitening secret! www.consumertipsweekly.net 1 Tip To A Sexy Stomach Learn How I Cut Down 12 lbs quickly. See Consumer Health News! www.HealthNews.com Acai Berry Diet EXPOSED (Official Report) Looking to Lose Weight? Read This Warning Before Buying! News18TV.com Buy a link here MORE FROM PARADE Obama 'Deeply Malin Akerman: Don't Charitable Celebrities A Team of Doctors Will Eye Care Tips For An Actor Eyes a Bigger Humbled' By Nobel Make A Hollywood See You Now Every Situation Purpose Peace PARADE.COM 1 of 2 10/9/2009 11:55 PM Eileen Coleman, 35 - Real People, Real Salaries | Parade.com http://www.parade.com/news/what-people-earn/slideshows/real-people-... Home CELEBRITY HEALTH & FOOD SPECIAL REPORTS MAGAZINE Contact Us Interviews -

The Winners Tab

The Winners Tab 2013 BETTER NEWSPAPERS CONTEST AWARDS PRESENTATION: SATURDAY, MAY 3, 2014 CALIFORNIA NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION INSIDE ESTABLISHED 1888 2 General Excellence 5 Awards by Newspaper 6 Awards by Category 10 Campus Awards normally loquacious violinist is prone to becoming overwhelmed with emotion The Most Interesting Man in the Phil when discussing the physical, psychologi- How Vijay Gupta, a 26-Year-Old Former Med Student, cal and spiritual struggles of his non-Dis- Found Himself and Brought Classical Music to Skid Row ney Hall audience. “I’m this privileged musician,” he said recently. “Who the hell am I to think that I By Donna Evans could help anybody?” On a sweltering day in late August, raucous applause. Chasing Zubin Mehta Los Angeles Philharmonic violinist Vijay Screams of “Encore!” are heard. One Gupta will be front and center this week Gupta steps in front of a crowd and bows man, sitting amidst plastic bags of his when the Phil kicks off the celebration of his head to polite applause. belongings, belts out a curious request for the 10th anniversary of Walt Disney Con- He glances at the audience and surveys Ice Cube. Gupta and his fellow musicians, cert Hall. Along with the 105 other mem- the cellist and violist to his left . He takes Jacob Braun and Ben Ullery, smile widely bers of the orchestra, he’ll spend much of a breath, lift s his 2003 Krutz violin and and bow. the next nine months in formal clothes tucks it under his chin. Once it’s settled, Skid Row may seem an unlikely place and playing in front of affl uent crowds. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Report for America's Host Newsroom Partners for 2021-2022 (Current And

Report for America’s host newsroom partners for 2021-2022 (current and new) State Newsroom Beat(s) Anchorage Daily News / AK adn.com Healthcare and public health in Alaska AK KCAW Coverage of Sitka and surrounding communities AK Fairbanks Daily News-Miner Health care in rural Alaska AK KUCB Regional reporting in the Eastern Aleutians 1) Child wellness and mental health in Alabama 2) AL AL.com educational opportunity in Birmingham AL Montgomery Advertiser Alabama's rural "Black Belt" region AL WBHM Education in Birmingham, AL AR Southwest Times Record Food insecurity and poverty in Fort Smith, AR KAWC Colorado River Public AZ Media Latino communities in Yuma County African-American and Latino communities in South AZ The Arizona Republic Phoenix Arizona Center for AZ Investigative Reporting Health care crises on the Arizona-Mexico border AZ Nogales International Eastern Santa Cruz County, AZ AZ TucsonSentinel.com Government accountability and equity issues in Tucson State-by-state data journalism to serve legislative CA Associated Press--Data reporters nationwide Growth and development in San Diego County's CA inewsource backcountry Inequality and income disparities in the Mission District CA Mission Local of SF CA Radio Bilingüe, Inc. San Joaquin Valley Latino community Education, childhood trauma and the achievement gap CA Redding Record Searchlight in and around Redding The effect of environmental regulation on salmon runs, wildfires, the economy and other issues in Mendocino CA The Mendocino Voice County, CA Childhood poverty in San -

Feasibility Report on Developing a Central Valley Journalism Collaborative

Feasibility Report on Developing a Central Valley Journalism Collaborative Released on July 13, 2021 for the James B. McClatchy Foundation Central Valley Journalism Collaborative 5 February 2021 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction a. Letter from JBMF CEO ..................................................03 2 Overview a. Executive Summary ......................................................05 Community Funding Model ..........................................06 A New Beginning? ....................................... ...... ............ 07 The Challenge Up Close ................................................08 The Way Forward ...........................................................08 Goals ................................................................................09 b. Strategic Leadership ..................................................... 10 c. Market Analysis ...............................................................11 d. A New Third Force in the Market .................................15 3 End Notes a. Report Infographics ........................................................17 b. Source Endnotes ...........................................................20 c. Partner with Us ................................................................21 d. Authors, Acknowledgements, About JBMF .............. 22 Central Valley Journalism Collaborative Overview 2 Letter from the James B. McClatchy Foundation California’s iconic Highway 99 has taken me through the blossoming fruit trees of Newman along Highway 33, up the orange -

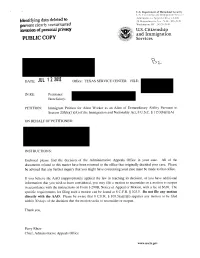

PUBLIC COPY Services

U.S. Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immiuration Service Adrninistrmive Appeals ()llke (AA()) identifying data deleted to 20 Massachusens Avn N.W MS 2(NO prevent clearly unwarranted Washinuton. DC 2052%2090 invasion of personal privacy U.S. Citizenship and Immigration PUBLIC COPY Services DATE: JUL 1 2 2012 Office: TEXAS SERVICE CENTER FILE: IN RE: Petitioner: Beneficiary: PETITION: Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker as an Alien of Extraordinary Ability Pursuant to Section 203(b)(1)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1153(b)(1)(A) ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: INSTRUCTIONS: Enclosed please find the decision of the Administrative Appeals Office in your casc. All of the documents related to this matter have been returned to the office that originally decided your case. Please be advised that any further inquiry that you might have concerning your case must be made to that office. If you believe the AAO inappropriately applied the law in reaching its decision, or you have additional information that you wish to have considered, you may file a motion to reconsider or a motion to reopen in accordance with the instructions on Form I-290B, Notice of Appeal or Motion, with a fee of $630. The specific requirements for filing such a motion can be found at 8 C.F.R. § 103.5. Do not file any motion directly with the AAO. Please be aware that 8 C.F.R. § 103.5(a)(1)(i) requires any motion to be filed within 30 days of the decision that the motion seeks to reconsider or reopen. -

Pinedale Historic Resource Survey

Pinedale Historic Resource Survey October 2007 Prepared for the City of Fresno Planning & Development Department 2600 Fresno Street Fresno, CA 93721 Prepared by Planning Resource Associates, Inc. 1416 N. Broadway Fresno, CA 93721 CITY OF FRESNO Pinedale Historic Resource Survey Final - October 2007 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary...........................................................................................................................1 II. Introduction........................................................................................................................................2 III. Methodology.......................................................................................................................................2 IV. Property Setting.................................................................................................................................3 V. Historical Overview...........................................................................................................................4 VI. Architectural Styles and Property Types Observed......................................................................10 VII. Potential Signifi cance Criteria........................................................................................................12 National Register of Historic Places..................................................................................12 California Register of Historical Resources......................................................................12 -

Note Available from Pub Type Descriptors Abstract

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 357 176 CE 063 506 AUTHOR Hayes, Holly, Ed.; Marmolejo, Jill, Ed. TITLE Bee a Reader. INSTITUTION Fresno Bee, CA. PUB DATE Jun 89 NOTE 158p. AVAILABLE FROM Fresno Bee, 1626 E Street, Fresno, CA 93786-0001 (free). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy;Adult Reading Programs; Behavioral Objectives; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; *Literacy Education; *Newspapers; *Reading Instruction; Teaching Guides; Vocabulary Development IDENTIFIERS *Fresno Bee ABSTRACT This publication is a tutor's guide to teaching basic literacy using The Fresno Bee, a Californianewspaper, as the primary "textbook." The course is aimed at English-speakingadults and is designed to teach reading in an interesting and entertainingway that promotes self-motivated study, both in the classroom andat home. The guide is divided into three parts, each with 25 lessons.Designed for the nonreader who knows almost nothing about language, noteven the sounds of the letters, Part I begins with letters andsounds and introduces students to the reading of basic words. The printedand cursive alphabets are introduced, along with the conceptof alphabetization. Designed for students who havesome knowledge of sounds and words, either through pretutoringor folloaing the lessons in Part I, Part II begins with a review of theletters and sounds, then moves into longer words, basic sentence structure,and basic punctuation. Designed for students who havesome basic reading ability but whneed vocabulary practice and work on practical reading, Part III begins with a review of the conceptscovered in Parts I and II and then continues withmore vocabulary development and practical reading: more on alphabetization, using advertising, reading maps, using indexes, categorization, writing basicletters, and filling out forms. -

An Information Ecosystem Assessment of South Fresno and Surrounding Rural Communities

AN INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT OF SOUTH FRESNO AND SURROUNDING RURAL COMMUNITIES JULY 2019 Report by The Listening Post Collective, a project of Internews INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT SOUTH FRESNO & SURROUNDING RURAL COMMUNITIES ABOUT THIS REPORT: The Listening Post Collective is a community media initiative that works with local partners to engage, inform and support communities across the U.S. that are underserved by mainstream news coverage. We believe information changes lives. The Listening Post Collective is a project of Internews, an international nonprofit that works globally to build healthy media ecosystems where they are most needed. After working for 30 years to increase access to vital information in challenging environments in more than 100 countries, Internews recognized that the very same information problems — lack of trust in the media, lost community connection and populations entirely left out of the conversation — were growing in the U.S. as well. With local journalism outlets closing or downsizing, communities across the U.S are losing access to critical sources of information that hold power to account and help people make informed decisions about their lives. Our mission is to build healthy information ecosystems that are a direct response to people’s informational needs, resulting in more connected, empowered and inclusive communities. Borrowed from environmental studies, the term “information ecosystem” describes how communities exist within particular information and communication systems. Within these systems, information is created and shared through word of mouth, key community members, phone, the Internet and more. An assessment of an information ecosystem looks at the flow, use, trust and impact of news and information. -

06Cv233 Martinez V. Fresno July 16

Case 1:06-cv-00233-OWW -SKO Document 294 Filed 07/16/09 Page 1 of 13 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 2 FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 3 4 LUPE E. MARTINEZ, on behalf of herself 5 and all similarly situated, RALPH C. 1:06-CV-00233 OWW GSA RENDON, on behalf of himself and all 6 similarly situated, [Consolidated with 1:06-cv-01851] 7 Plaintiffs, 8 MEMORANDUM DECISION AND v. ORDER DENYING 9 DEFENDANTS’ MANFREDI AND CITY OF FRESNO; JERRY DYER, Chief of TAFOYA’S MOTION FOR 10 the Fresno Police Department, SGT. TRANSFER OF VENUE (DOC. MICHAEL MANFREDI, OFFICER MARCUS K. 217) 11 TAFOYA, OFFICER BELINDA ANAYA, and DOES 1-20, in their individual and official 12 capacities, inclusive, 13 Defendants. 14 15 CALUDIA RENDON, GEORGE RENDON, PRISCILLA RENDON, LAWRENCE RENDON, 16 RICARDO RENDON, JOHN NUNEZ, JR., ALFRED 17 HERNANDEZ, AND VIVIAN CENTENO, 18 Plaintiffs, 19 v. 20 CITY OF FRESNO, JERRY DYER, individually and in his official 21 capacity as the Chief of Police for the 22 Fresno Police Department; MICHAEL MANFREDI, individually and in his 23 official capacity as Police Officer of the Fresno Police Department, BELINDA 24 ANAYA, individually and in her official capacity as a Police Officer for the 25 Fresno Police Department, and DOES 1 26 through 50, inclusive, 27 Defendants. 28 1 Case 1:06-cv-00233-OWW -SKO Document 294 Filed 07/16/09 Page 2 of 13 1 Before the court for decision is Defendants’ Michael 2 Manfredi and Marcus K. Tafoya’s motion for transfer of venue to 3 4 the Sacramento Division pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, 5 section 1404(A). -

Fall 2009 Catalog

What’s Next in Your Life? Fall 2009 Calendar “I love these lectures—it is great to be retired and keep going to classes. Learning never ends!” Throughout this brochure, you will find quotes from OLLI members about our programs and instructors. Why not join us and learn about OLLI firsthand? Our thanks to OLLI Members Herb Thorne and John Dunn for providing some of the photos used in this brochure. What’s Next in Your Life? he Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) at Cali- GENERAL MEMBERSHIP – Fee $55 single, $90 couple fornia State University, Fresno, is designed for adults • Admission to all six (6) General Sessions scheduled age 50+ who wish to continue learning and exploring for during the Fall 2009 semester Tthe sheer joy of it. Renew your enthusiasm for learning in • Opportunity to sign up for Short Courses and Field a relaxed atmosphere, without entrance requirements, Trips (see schedule for details) grades or exams. • Free parking on campus during all General Session events and Short Courses Funded in part by the Bernard Osher Foundation, the • Madden Library privileges OLLI is a vibrant learning community offering a rich array • Reduced admission fees at Fresno area museums of workshops, short courses, and field trips of particular • OLLI-Mail announcements of Fresno State events interest to retired or semi-retired adults. via email We have an exciting schedule of activities that will chal- ASSOCIATE MEMBERSHIP – Fee $15 per person lenge, inspire, and motivate you—why not join us today? • Admission to TWO (2) General Session events (your choice) during the Fall 2009 semester Membership Information • Opportunity to sign up for Short Courses and Field Trips (see schedule for details) resno State’s OLLI has a variety of choices for member • Free parking on campus during two (2) General participation, ranging from General and Associate Session events and Short Courses memberships to short courses and field trips. -

Smittcamp

Viewonline ALUMNI NEWS DE C. 2015 ..• TOP STORIES ._. SCHOLARSHARE ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT Othe,· top news ... Alumni become leaders of their own college writing centers University Theatre to present 'Really Really' University mourns t he passing of alumnus Dr. Harry Moordigian Joseph I. Castro: Pell Grant helped pave my road to college Alumnus establishes scholarship endowment in memory of public health student Dr. Saul J imenez·Sandoval named dean of College of Arts and Humanities Winemaking: A growing tradition Cl·M·i University serves 335 veterans with three programs II@ CLASS NOTES Rico Guerrero {1998}has been named the Mary Piona (Alumna}, a local farmer, is executive director of t he State Center Community highlighted in The Fresno Bee's photo exhibit titled College District. He has worked previously for t he •Faces of the Drought:· Fresno Regional Foundation and the Boys & Girls Clubs of Fresno County. Amanda l ittle (2004/established and owns Make Pie Not War - a business that hand makes necklaces, Joe Del Bosque (1975} has been named the bracelets and rings made in the conver ted garage to 2015 Agricu lturist of the Year by the Fresno about 40 boutiques nationwide and one in Japan. Chamber of Commerce. The west-side farmer, who The business is also a finalist in the Martha Stewart gave President Barack Obama a tour of his American Made awards. Read more drought-stricken land last year. Founded in 1985, Empresas Del Bosque Inc. began as a small Candy Tsang {1981}climbed Mount Kilimanjaro operation led by Del Bosque and his wife, Maria.