Planokc Comprehensive Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Court Moving to Salem

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2017 Marblehead superintendent Housing vows to address hate crimes court By Bridget Turcotte tance of paying attention to racial in- Superintendent Maryann Perry said ITEM STAFF justices within the walls of the building. in a statement Friday afternoon that in moving “We did this for people to understand light of Thursday’s events, “we continue MARBLEHEAD — A day after more that the administration needs to do to move forward as an agent of change than 100 students protested what they considered a lack of response from the more about this and the kids should in our community. be more educated that that word is not “As a result of ongoing conversations to Salem school’s administration to racially-mo- tivated incidents, the superintendent supposed to be used,” said Lany Marte, that have been occurring, including dis- vowed to give them a voice. a 15-year-old student who helped orga- cussions with students and staff that By Thomas Grillo When the clock struck noon on Thurs- nize the protest. “We’re going to be with took place today, we will be working ITEM STAFF day, schoolmates stood in solidarity out- each other for four years and by saying closely with Team-Harmony and other side Marblehead High School, holding that word and spreading hate around LYNN — Despite opposition from ten- signs and speaking about the impor- the school, it’s not good.” MARBLEHEAD, A7 ants and landlords, the Lynn Housing Court will move to Salem next month. The decision, by Chief Justice Timothy F. Sullivan, comes on the heels of a public hearing on the court’s closing this week where dozens of housing advocates told the judge to consider alternatives. -

Emergency Operations Plan

EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN 2017 RECORD OF CHANGES Each interim change made between adoptions of the EOP by City Council will be recorded by the person making changes on this form by indicating the date the change was made and person making the change. In addition, the document directing the change will be filed behind this page. CHANGE # NAME OF PERSON MAKING CHANGE DATE OKC EOP 06/2017 DISTRIBUTION The City of Oklahoma City provides copies of the official City of Oklahoma City Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) in an electronic format only. Persons or organizations wishing to have hard (printed) copies of the EOP will be responsible for printing it and paying any printing costs. Electronic copies of the official City of Oklahoma City Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) will be available to all City employees at the City’s intranet site. Each City Department Head or their designee shall keep a hard (printed) copy of the current up-to- date EOP on file and available in their Department. Each Department is responsible for printing a copy of the EOP from the City’s intranet site. Electronic copies of the official City of Oklahoma City Emergency Operations Plan may be distributed as needed or upon request to other government, non-profit organizations and private sector stakeholders with assigned responsibilities under the plan. OKC EOP 06/2017 The City of Oklahoma City Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) BASIC PLAN Contents PURPOSE, SCOPE, SITUATIONS, AND ASSUMPTIONS........................................................ 5 PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

August 6, 2021 Broadcast Eeo Audit Radio & Television

AUGUST 6, 2021 BROADCAST EEO AUDIT RADIO & TELEVISION STATIONS CALL SIGN SERVICE CITY OF LICENSE STATE FACILITY ID LICENSEE NAME KBZZ AM SPARKS NV 48684 AMERICOM LIMITED PARTNERSHIP KFBX AM FAIRBANKS AK 12518 IHM LICENSES, LLC KFLG AM BULLHEAD CITY AZ 65676 CAMERON BROADCASTING, INC. KIHM AM RENO NV 53707 RELEVANT RADIO, INC. KIPA AM HILO HI 33324 CSN INTERNATIONAL KKOH AM RENO NV 11236 RADIO LICENSE HOLDING CBC, LLC KNBR AM SAN FRANCISCO CA 35208 RADIO LICENSE HOLDING SRC LLC KNZR AM BAKERSFIELD CA 7715 ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC KOGO AM SAN DIEGO CA 51514 IHM LICENSES, LLC KSEI AM POCATELLO ID 51216 IDAHO WIRELESS CORPORATION KUGN AM EUGENE OR 12506 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC KXEW AM SOUTH TUCSON AZ 8144 IHM LICENSES, LLC KZMQ AM GREYBULL WY 5245 LEGEND COMMUNICATIONS OF WYOMING, LLC WBRG AM LYNCHBURG VA 67704 TRI-COUNTY BROADCASTING, INC. WCTC AM NEW BRUNSWICK NJ 55180 BEASLEY MEDIA GROUP LICENSES, LLC WCTF AM VERNON CT 20826 FAMILY STATIONS, INC. WDVA AM DANVILLE VA 43244 MITCHELL COMMUNICATIONS, INC. WFAN AM NEW YORK NY 28617 ENTERCOM LICENSE, LLC WFEA AM MANCHESTER NH 58543 SAGA COMMUNICATIONS OF NEW ENGLAND, LLC WFGL AM FITCHBURG MA 8418 HORIZON CHRISTIAN FELLOWSHIP WHGB AM HARRISBURG PA 32944 CUMULUS LICENSING LLC WIOV AM READING PA 55307 RADIO LICENSE HOLDING CBC, LLC KAIK FM ROCKAWAY BEACH OR 93900 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION KAIX FM CASPER WY 92997 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION KARJ FM ESCONDIDO CA 49206 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION KARO FM NYSSA OR 57066 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION KARQ FM SAN LUIS OBISPO CA 52246 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

Media Guide for Federal Leaders in Oklahoma

Media Guide for Federal Agencies Discussing the traditional forms of Media Interaction AND addressing the topic of Social Media! Oklahoma Federal Executive Board 215 Dean A. McGee, Suite 320 Oklahoma City, OK 73102 (405) 231-4167 www.oklahoma.feb.gov Distributed July 2011 INTRODUCTION Federal agencies have a responsibility to provide accurate and timely information to the general public and the media. In many cases, however, agencies do not have a person designated and trained as a Public Affairs Officer (PAO). In such instances, the CEO or a front-line employee must act as the agency's representative to the public. Many times, the intended message may be lost during the interview; often lack of planning or an inability to relay the message in succinct, easy to understand terms is the cause. Dealing with the media can be a daunting, nerve-wracking experience, whether it is in a face-to-face interview, phone interview or on camera. It is important to be at your best when communicating your message. This guide has been developed to assist those individuals called upon to speak on behalf of their agency to the press, both managerial and non-managerial employees. Whether you are responding to inquiries, arranging or participating in an interview, or simply providing information for print or broadcast, it is hoped that this media guide will provide you with useful information and some important tips to assist you. The purpose of this Media Guide is informational in nature for public employees. As in the past, the guidance is based on the principle that the business of Government is vital to serving the public everywhere. -

Thunder 2020-21 Game Notes

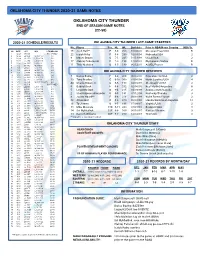

OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER 2020-21 GAME NOTES OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER END OF SEASON GAME NOTES (22-50) 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER LAST GAME STARTERS No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. Birthdate Prior to NBA/Home Country NBA Yr. NO DATE OPP W/L **TV/RECORD 15 Josh Hall** F 6-8 200 10/08/00 Moravian Prep/USA R 1 12/23 @ HOU POSTPONED 22 Isaiah Roby F 6-8 230 02/03/98 Nebraska/USA 2 2 12/26 @ CHA W, 109-107 1-0 9 Moses Brown C 7-1 245 10/13/99 UCLA/USA 2 3 12/28 vs. UTA L, 109-110 1-1 4 12/29 vs. ORL L, 107-118 1-2 17 Aleksej Pokuševski F 7-0 195 12/26/01 Olympiacos/Serbia R 5 12/31 vs. NOP L, 80-113 1-3 6 1/2 @ ORL W, 108-99 2-3 11 Théo Maledon G 6-5 180 06/12/01 ASVEL/France R 7 1/4 @ MIA L, 90-118 2-4 8 1/6 @ NOP W, 111-110 3-4 OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER RESERVES 9 1/8 @ NYK W, 101-89 4-4 10 1/10 @ BKN W, 129-116 5-4 11 1/12 vs. SAS L, 102-112 5-5 7 Darius Bazley F 6-8 208 06/12/00 Princeton HS/USA 2 12 1/13 vs. LAL L, 99-128 5-6 13 Tony Bradley C 6-10 260 01/08/98 North Carolina/USA 4 13 1/15 vs. CHI W, 127-125 (OT) 6-6 44 Charlie Brown Jr. -

Packages & Channel Lineup

™ ™ ENTERTAINMENT CHOICE ULTIMATE PREMIER PACKAGES & CHANNEL LINEUP ESNE3 456 • • • • Effective 6/17/21 ESPN 206 • • • • ESPN College Extra2 (c only) (Games only) 788-798 • ESPN2 209 • • • • • ENTERTAINMENT • ULTIMATE ESPNEWS 207 • • • • CHOICE™ • PREMIER™ ESPNU 208 • • • EWTN 370 • • • • FLIX® 556 • FM2 (c only) 386 • • Food Network 231 • • • • ™ ™ Fox Business Network 359 • • • • Fox News Channel 360 • • • • ENTERTAINMENT CHOICE ULTIMATE PREMIER FOX Sports 1 219 • • • • A Wealth of Entertainment 387 • • • FOX Sports 2 618 • • A&E 265 • • • • Free Speech TV3 348 • • • • ACC Network 612 • • • Freeform 311 • • • • AccuWeather 361 • • • • Fuse 339 • • • ActionMAX2 (c only) 519 • FX 248 • • • • AMC 254 • • • • FX Movie 258 • • American Heroes Channel 287 • • FXX 259 • • • • Animal Planet 282 • • • • fyi, 266 • • ASPiRE2 (HD only) 381 • • Galavisión 404 • • • • AXS TV2 (HD only) 340 • • • • GEB America3 363 • • • • BabyFirst TV3 293 • • • • GOD TV3 365 • • • • BBC America 264 • • • • Golf Channel 218 • • 2 c BBC World News ( only) 346 • • Great American Country (GAC) 326 • • BET 329 • • • • GSN 233 • • • BET HER 330 • • Hallmark Channel 312 • • • • BET West HD2 (c only) 329-1 2 • • • • Hallmark Movies & Mysteries (c only) 565 • • Big Ten Network 610 2 • • • HBO Comedy HD (c only) 506 • 2 Black News Channel (c only) 342 • • • • HBO East 501 • Bloomberg TV 353 • • • • HBO Family East 507 • Boomerang 298 • • • • HBO Family West 508 • Bravo 237 • • • • HBO Latino3 511 • BYUtv 374 • • • • HBO Signature 503 • C-SPAN2 351 • • • • HBO West 504 • -

Community Reactions to Sonic Booms in the Oklahoma City Area Volume Ii

COMMUNITY REACTIONS TO SONIC BOOMS IN THE OKIAHOMA CITY AREA Volume I: Major Findings PAUL N. BORSKY I: Report No. 101 January 1965 COMMNITY RECTIONS TO SONIC BOOMS lahoma City Area February-July 1964 Part l. Major Findings Paul N. Borsky Senior Study Director NATIONAL OPINION RESEARCH CENTER University of Chicago 55 Fifth Avenue New York 10003 LIBRA. R Report No. 101 NA 'nONAL OP!NRON RE8EARCH CENR January 1965 University of Chicago FILE COpy .. .. .. ... ... .... .... ... ... ... ... .... .... .. ... ... ... ... ... .... .... ..."----"-- Table of Contents Page SUMY. A. Research Approach. B. Reported Overall Reactions to Sonic Booms in Oklahoma City Area 1. Interference with ordinary living activities. 2. Annoyance with sonic booms. 3. Desires to complain and actual complaints about sonic booms 4. Long ranee acceptability of sonic booms C. The Expected Range in Public Reactions to Sonic Booms. 1. Range in annoyance reactions to sonic booms 2. Range in reported desires to complain and actual complaints about sonic booms. 3. Range in reported long range acceptability of sonic booms D. Other Related Findings 1. General factors affecting complaints in Oklahoma City. 2. Importance of aviation to Oklahoma City 3. Importance of belief that sonic booms cause damage. 4. General reliability of interview responses. 5. Relation of distance from SST flight track and reactions to sonic boom. 6. Reactions of urban and rural p9pulations. 7. Effects of night booms on community reactions INTRODUCTION III CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ACTUAL SONIC BOOM EXPOSURS PERSO INTERVIEW FINDINGS. A. Number and Type of Interviews. B. Some Basic Characteristics of the Oklahoma City Area r-- LIB R. A R y NA' frONA NKON '- E!,dEA. -

Summer/Fall 1997 a Newsletter About the Employees and Activities of the National Severe Storms Laboratory

NSSL Briefings Volume 2 No. 1 Summer/Fall 1997 A newsletter about the employees and activities of the National Severe Storms Laboratory Left box: Observed frontal location, modeled rainfall 0000 U TC 27 April during1991 the past hour (green), and observed severe reports (tornado as an inverted triangle; severe wind as a +; hail as a dot) Right box: Model parameters used 00 to determine likelihood of tornadic thunderstorms overlaid on a single figure. Region where tornadic 56 thunderstorms are most likely indicated by the color- filled sections in the right box that overlap where rainfall is simulated in the left box. 118 59 than the movement of the thunderstorm, the 39 raindrops produced in the storm updraft get blown 2 73 away from the storm, and the cooling effect of the 74 87 rain has little effect on the storm evolution. In 10 contrast, when the winds in the atmosphere are much slower than the movement of the thunder- storm, the raindrops all fall very close to the center of the storm, cooling the air near the ground and Forecasting producing very strong outflow. In between these two extremes, the winds in the atmosphere are tornadic roughly equal to the movement of the thunder- storm, and just the right amount of rainfall reaches the ground near the center of the storm. In this thunderstorms case, the cooling effect of the rain can be used to help generate rotation in the thunderstorm at levels by Dave Stensrud and Harold Brooks near the ground surface. This increases the likelihood of tornado formation. -

1 MAJOR BROADCASTERS LAUNCH NEXTGEN TV on FIVE LOCAL TELEVISION STATIONS in OKLAHOMA CITY, OK KOCO-TV, KFOR-TV, KOKH-TV, KOCB A

MAJOR BROADCASTERS LAUNCH NEXTGEN TV ON FIVE LOCAL TELEVISION STATIONS IN OKLAHOMA CITY, OK KOCO-TV, KFOR-TV, KOKH-TV, KOCB and KAUT Begin Broadcasting with New Technology Oklahoma City, OK – October 8, 2020 – Five leading local television stations in Oklahoma City, OK, including KOCO-TV (ABC), KFOR-TV (NBC), KOKH-TV (Fox), KOCB (CW) and KAUT (IND), today became among the first in the nation to begin broadcasting with NEXTGEN TV, a revolutionary new digital broadcast technology. Based on the same fundamental technology as the Internet, digital applications, and other web services, NEXTGEN TV can support a wide range of features currently in development, such as immersive audio and video (up to 4K), broadcasting to mobile devices, personalized viewing tools, and advanced emergency alerts providing rich media instead of simple text messages. NEXTGEN TV also allows full integration with 5G and other broadband-delivered Internet content. Powered by ATSC 3.0, NEXTGEN TV is the most significant broadcast technology upgrade ever. Today’s launch in Oklahoma City is one of the first in the country for NEXTGEN TV and follows a decade of development of the new technology and months of planning and preparation by the local stations. BitPath, which is developing new data broadcasting services, led the planning process and coordinated efforts across the five television stations. The participating stations have cooperated to ensure that current programming remains available to all viewers, regardless of whether their television service is provided over-the air or by a cable or satellite company. Antenna viewers can simply rescan their TV sets to ensure full service. -

1-9-20Malsenido, Natalia Resume Pg

Natalia Malsenido Represented by The NWT Group [email protected] 817-987-3600 https://NWTgroup.com/client/nataliamalsenido EXPERIENCE KLAS-TV, Las Vegas, NV Producer Jan. 2020 – Present Skills/Accomplishments KOKH FOX, Oklahoma City, OK Lifestyle Producer • Fluent speaking, writing and “Living Oklahoma” & "Al Día con FOX 25” reading in English and Spanish Sept. 2015 – September 2019 • Develop and execute editorial content and creative direction of a daily live show • Adobe Audition, EDIUS, Final and weekly digital show in Spanish Cut, and DSLR, JVC-HD • Selection and booking of guests, musical acts, interviews and other segments cameras for the content of each show in English and Spanish • Oversight of hosts and production team • iNews, News King • Responsible for coordination of sales integrated segments • Generates content initiatives and special projects to grow English and Spanish • News Director ‘Oklahoma audiences Institute for Diversity in Journalism” KTUZ Telemundo, Oklahoma City, OK Producer/Weekend Anchor • Special Adviser; University of “Accion Oklahoma” Oklahoma “OU Nightly En Oct. 2014 – Sept. 2015 Español” • Responsible for editorial content, writing, editing, graphics of live daily news- casts • VP, NAHJ Oklahoma • Presenting “Accion Oklahoma” live weekend newscasts in addition to producing • Created and delivered digital content for the website and social media platforms KTUZ Telemundo, Oklahoma City, OK Reporter/MMJ Oct. 2013 – Sept. 2015 • Developed connections in the Hispanic community to generate impactful story ideas and local angels to big stories • Shoot, write and edit stories for broadcast and digital platforms Social Media • Reported live in the field several times a week Natalia-Malsenido KTUZ Telemundo, Oklahoma City, OK 10PM Producer “Accion Oklahoma” @NMalsenido1 2013 – 2014 NataliaMalsenido @NataliaMalsenido EDUCATION University of Central Oklahoma 2014 .