Update on Brook Trout Rehabilitation in the Ontario Waters of Lake Superior, Lake Nipigon, and the Nipigon River: Public Workshop Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

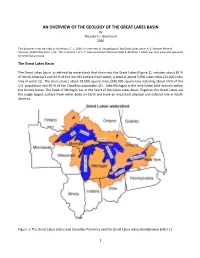

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

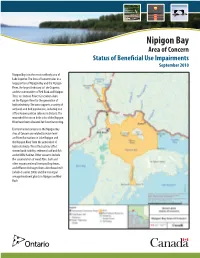

Nipigon Bay Area of Concern Status of Beneficial Use Impairments September 2010

Nipigon Bay Area of Concern Status of Beneficial Use Impairments September 2010 Nipigon Bay is in the most northerly area of Lake Superior. The Area of Concern takes in a large portion of Nipigon Bay and the Nipigon River, the largest tributary to Lake Superior, and the communities of Red Rock and Nipigon. There are Ontario Power Generation dams on the Nipigon River for the generation of hydroelectricity. The area supports a variety of wetlands and bird populations, including one of four known pelican colonies in Ontario. The watershed forests on both sides of the Nipigon River have been allocated for forest harvesting. Environmental concerns in the Nipigon Bay Area of Concern are related to water level and flow fluctuations in Lake Nipigon and the Nipigon River from the generation of hydroelectricity. These fluctuations affect stream bank stability, sediment load and fish and wildlife habitat. Other concerns include the accumulation of wood fibre, bark and other organic material from past log drives, and effluent discharges from a linerboard mill (which closed in 2006) and the municipal sewage treatment plants in Nipigon and Red Rock. PARTNERSHIPS IN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Nipigon Bay was designated an Area of Concern in 1987 under the Canada–United States Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Areas of Concern are sites on the Great Lakes system where environmental quality is significantly degraded and beneficial uses are impaired. Currently, there are 9 such designated areas on the Canadian side of the Great Lakes, 25 in the United States, and 5 that are shared by both countries. In each Area of Concern, government, community and industry partners are undertaking a coordinated effort to restore environmental quality and beneficial uses through a remedial action plan. -

More Than Just a Lake! TOPIC Great Lake Drainage Basins AUDIENCE Grades 1-6; 10-30 Students

More Than Just a Lake! TOPIC Great Lake drainage basins AUDIENCE Grades 1-6; 10-30 students SETTING By creating a map of the rivers flowing into your Great Lake, Large, open indoor space is learn how rivers form a watershed. required GOAL To understand the concept of a drainage basin or watershed, and how that concept relates to the BACKGROUND around the lake as gravity pulls water local Great Lake watershed. All lakes and rivers have a set area to the lowest point. Water draining of land that water drains into them to the lowest common point is the OBJECTIVES • Students will understand the from, called the “watershed” or simplest definition of a watershed. defining role that rivers have “drainage basin.” Drainage basins are in watershed activity important environmentally because 2. Introduction to the model • Students will be able to state whether they live inside or whatever happens within the basin of watershed outside the drainage basin of the lake can happen to the lake itself. Students gather around the “shore” their Great Lake Toxic substances spilled or placed of the lake. Explain that the blue • Older students will be able to identify the river drainage on the land or in watershed rivers yarn represents rivers. With younger basin in which they live can end up in the lake. See the Great students, demonstrate how one river Lakes Watershed Fact Sheets for ad- might look on the map as it flows MATERIALS ditional information about your local into your Great Lake. • Large floor map of your Great Lake (or an outline on the watershed. -

Lake Superior Food Web MENT of C

ATMOSPH ND ER A I C C I A N D A M E I C N O I S L T A R N A T O I I O T N A N U E .S C .D R E E PA M RT OM Lake Superior Food Web MENT OF C Sea Lamprey Walleye Burbot Lake Trout Chinook Salmon Brook Trout Rainbow Trout Lake Whitefish Bloater Yellow Perch Lake herring Rainbow Smelt Deepwater Sculpin Kiyi Ruffe Lake Sturgeon Mayfly nymphs Opossum Shrimp Raptorial waterflea Mollusks Amphipods Invasive waterflea Chironomids Zebra/Quagga mussels Native waterflea Calanoids Cyclopoids Diatoms Green algae Blue-green algae Flagellates Rotifers Foodweb based on “Impact of exotic invertebrate invaders on food web structure and function in the Great Lakes: NOAA, Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, 4840 S. State Road, Ann Arbor, MI A network analysis approach” by Mason, Krause, and Ulanowicz, 2002 - Modifications for Lake Superior, 2009. 734-741-2235 - www.glerl.noaa.gov Lake Superior Food Web Sea Lamprey Macroinvertebrates Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). An aggressive, non-native parasite that Chironomids/Oligochaetes. Larval insects and worms that live on the lake fastens onto its prey and rasps out a hole with its rough tongue. bottom. Feed on detritus. Species present are a good indicator of water quality. Piscivores (Fish Eaters) Amphipods (Diporeia). The most common species of amphipod found in fish diets that began declining in the late 1990’s. Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Pacific salmon species stocked as a trophy fish and to control alewife. Opossum shrimp (Mysis relicta). An omnivore that feeds on algae and small cladocerans. -

Danahub 2021 – Reference Library E & O E Overview the Great Lakes Region Is the Living Hub of North America, Where It

Overview The Great Lakes region is the living hub of North America, where it supplies drinking water to tens of millions of people living on both sides of the Canada-US border. The five main lakes are: Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Combined, the Great Lakes contain approximately 22% of the world’s fresh surface water supply. Geography and Stats The Great Lakes do not only comprise the five major lakes. Indeed, the region contains numerous rivers and an estimated 35,000 islands. The total surface area of the Great Lakes is 244,100 km2 – nearly the same size as the United Kingdom, and larger than the US states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire combined! The total volume of the Great Lakes is 6x1015 Gallons. This amount is enough to cover the 48 neighboring American States to a uniform depth of 9.5 feet (2.9 meters)! The largest and deepest of the Great Lakes is Lake Superior. Its volume is 12,100 Km3 and its maximum depth is 1,332 ft (406 m). Its elevation is 183 m above sea level. The smallest of the Great Lakes is Lake Erie, with a maximum depth of 64 m and a volume of 484 Km3. Lake Ontario has the lowest elevation of all the Great Lakes, standing at 74 m above sea level. The majestic Niagara Falls lie between Lakes Erie and Ontario, where there is almost 100 m difference in elevation. Other Rivers and Water Bodies The Great Lakes contain many smaller lakes such as Lake St. -

2018 Roadmap to Fishing Lake Superior: Have a Super Time!

Roadmap to Fishing Lake Superior: Have a Super Time! Want to fish Lake Superior, but aren’t sure when or where to go? This roadmap is a starting point to provide you with information on many fishing sites and times of the year when great opportunities exist. Please note this is not an exhaustive list. Eagle HarborCopper Harbor Traverse Bay Ontonagon Keweenaw Bay Black River Harbor Grand Marais Marquette Au Train-Shelter Bay St. Marys River Munising Black River Au Train- Ontonagon Eagle Harbor Copper Harbor Traverse Bay Keweenaw Bay Marquette Munising Grand Marais St. Marys River Port Harbor Shelter Bay brown trout, Chinook, cisco, coho, brown trout, Chinook, cisco, brown trout, Chinook, cisco, coho, brown trout, lake trout, lake whitefish, round coho, lake trout, lake whitefish, lake trout, lake whitefish, round coho, lake whitefish, n burbot, coho, cisco, walleye, yellow perch Feb - March whitefish, siscowet, smelt, splake, round whitefish, siscowet, smelt, whitefish, splake, steelhead, pike, yellow perch smelt, steelhead steelhead, yellow perch splake, steelhead, yellow perch yellow perch brown trout, Chinook, coho, lake brown trout, Chinook, coho, brown trout, Chinook, cisco, Chinook, cisco, coho, lake brown trout, Chinook, brown trout, Chinook, cisco, coho, Chinook, trout, lake whitefish, Chinook, coho, lake trout, coho, lake trout, round trout, lake whitefish, n pike, coho, lake trout, lake siscowet lake trout, lake whitefish, siscowet, coho, lake round whitefish, April - May lake trout, siscowet, whitefish, siscowet, smelt, sm bass, -

N Shore L. Superior: Geology, Scenery

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan Was Granted

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan was granted statehood on January 26, 1837, Michigan also acquired ownership of the Great Lakes' bottomlands under the equal footing doctrine.1 However before Michigan could become a state, the United States first had to acquire title from us (Ottawa and Chippewa bands) because Anglo-American law acknowledged that we owned legal title as the aboriginal occupants of the territory we occupied. But when we agreed to cede legal title to the United States in the March 28, 1836 Treaty of Washington ("1836 Treaty", 7 Stat. 491), we reserved fishing, hunting and gathering rights. Therefore, Michigan's ownership of both the lands and Great Lakes waters within the cession area of the 1836 Treaty was burdened with preexisting trust obligations with respect to our treaty-reserved resources. First, the public trust doctrine imposes a duty (trust responsibility) upon Michigan to protect the public trust in the resources dependent upon the quality of the Great Lakes water.2 In addition, Art. IV, § 52 of Michigan's Constitution says "conservation…of the natural resources of the state are hereby declared to be of paramount public concern…" and then mandates the legislature to "provide for the protection of the air, water and other natural resources from 3 pollution, impairment and destruction." 1 The State of Michigan acquired title to these bottomlands in its sovereign capacity upon admission to the Union and holds them in trust for the benefit of the people of Michigan. Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois, 146 U.S. 387, 434-35 (1892); Nedtweg v. -

Lake Ontario Lakewide Management Plan Status

LAKE ONTARIO LAKEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN STATUS APRIL 22, 2004 TAB L E O F CO NTEN TS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... ES-1 CHAPTER 1 STATE OF LAKE ONTARIO 1.1 Summary........................................................................................................................... 1-1 CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND 2.1 Summary........................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Introduction to Lake Ontario............................................................................................... 2-1 2.2.1 Climate.................................................................................................................. 2-2 2.2.2 Physical Characteristics and Lake Processes ............................................................ 2-2 2.2.3 Aquatic Communities............................................................................................. 2-4 2.2.4 Demographics and Economy of the Basin................................................................ 2-6 2.3 LaMP Background.............................................................................................................. 2-8 2.4 LaMP Structure and Processes............................................................................................. 2-9 2.5 Actions and Progress..........................................................................................................2-10 2.6 -

Sander Vitreus) ⁎ Ursula Strandberga, , Satyendra P

Environment International 112 (2018) 251–260 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environment International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envint Spatial and length-dependent variation of the risks and benefits of T consuming Walleye (Sander vitreus) ⁎ Ursula Strandberga, , Satyendra P. Bhavsarb, Tarn Preet Parmara, Michael T. Artsa a Ryerson University, Department of Chemistry and Biology, 350 Victoria St., Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada b Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, Sport Fish Contaminant Monitoring Program, Environmental Monitoring and Reporting Branch, 125 Resources Road, Toronto, ON M9P 3V6, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Handling Editor: Yong Guan Zhu Restricted fish consumption due to elevated contaminant levels may limit the intake of essential omega-3 fatty − − Keywords: acids, such as eicosapentaenoic (EPA; 20:5n 3) and docosahexaenoic (DHA; 22:6n 3) acids. We analyzed Risk-benefit lake- and length-specific mercury and EPA + DHA contents in Walleye (Sander vitreus; Mitchell 1818) from 20 Mercury waterbodies in Ontario, Canada, and used this information to calculate the theoretical intake of EPA + DHA Eicosapentaenoic acid when the consumption advisories are followed. The stringent consumption advisory resulted in decreased Docosahexaenoic acid EPA + DHA intake regardless of the EPA + DHA content in Walleye. Walleye length had a strong impact on the Sander vitreus EPA + DHA intake mainly because it was positively correlated with the mercury content and thereby con- Walleye sumption advisories. The highest EPA + DHA intake was achieved when smaller Walleye (30–40 cm) were consumed. The strong relationship between the consumption advisory and EPA + DHA intake enabled us to develop a more generic regression equation to estimate EPA + DHA intake from the consumption advisories, which we then applied to an additional 1322 waterbodies across Ontario, and 28 lakes from northern USA for which Walleye contaminant data are available but fatty acid data are missing. -

Petition to List US Populations of Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser Fulvescens)

Petition to List U.S. Populations of Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) as Endangered or Threatened under the Endangered Species Act May 14, 2018 NOTICE OF PETITION Submitted to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on May 14, 2018: Gary Frazer, USFWS Assistant Director, [email protected] Charles Traxler, Assistant Regional Director, Region 3, [email protected] Georgia Parham, Endangered Species, Region 3, [email protected] Mike Oetker, Deputy Regional Director, Region 4, [email protected] Allan Brown, Assistant Regional Director, Region 4, [email protected] Wendi Weber, Regional Director, Region 5, [email protected] Deborah Rocque, Deputy Regional Director, Region 5, [email protected] Noreen Walsh, Regional Director, Region 6, [email protected] Matt Hogan, Deputy Regional Director, Region 6, [email protected] Petitioner Center for Biological Diversity formally requests that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”) list the lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in the United States as a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544. Alternatively, the Center requests that the USFWS define and list distinct population segments of lake sturgeon in the U.S. as threatened or endangered. Lake sturgeon populations in Minnesota, Lake Superior, Missouri River, Ohio River, Arkansas-White River and lower Mississippi River may warrant endangered status. Lake sturgeon populations in Lake Michigan and the upper Mississippi River basin may warrant threatened status. Lake sturgeon in the central and eastern Great Lakes (Lake Huron, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River basin) seem to be part of a larger population that is more widespread. -

Quarterly Climate Impacts and Outlook for the Great Lakes Region

Quarterly Climate Impacts Great Lakes Region and Outlook December 2018 Great Lakes Significant Events –for September - November 2018 Extreme shifts from unseasonably warm to record cold temperatures occurred this fall season. For Cleveland, OH and Erie, PA, it was the second warmest September on record at 22°C and 21°C (70.7°F and 69.7°F), respectively. Many record warm temperatures occurred in the eastern lakes on October 8 and 9, when Erie tied its warmest October temperature on record at 32°C (89°F). Following extreme warmth early in the season, cold weather abruptly set in for November throughout the basin. The warmest temperature reached in Chicago during all of November was 11°C (52°F), the coldest mark since records began in 1871. Six counties in the central area of the upper peninsula of Michigan recorded their wettest October on record while Sault Ste. Marie, MI had its second wettest October with 19 cm (7 in) of precipitation. Toronto recorded its cloudiest November on record with an average cloud cover of 88% during daylight hours while 10 days during the month were cloudy 100% of the time. In addition, as of December 4, Chicago was having its second wettest year-to-date on record. Regional Climate Overview – for September - November 2018 Fall 2018 Temperature Precipitation and Temperature Departure from Normal September temperatures were up to 4°C (7°F) above normal, with the southern Erie basin being the warmest. October temperatures ranged from 3°C (5°F) below normal in the Superior basin to 3°C Great Lakes Water Levels (5°F) above normal in the southern Erie basin.