Maori Te Aroha Before the Opening of the Goldfield (Mostly Through Pakeha Eyes)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Draft.21

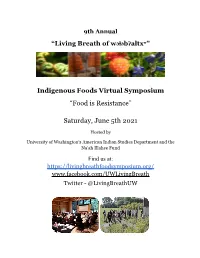

9th Annual “Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ” Indigenous Foods Virtual Symposium “Food is Resistance” Saturday, June 5th 2021 Hosted by University of Washington’s American Indian Studies Department and the Na’ah Illahee Fund Find us at: https://livingbreathfoodsymposium.org/ www.facebook.com/UWLivingBreath Twitter - @LivingBreathUW Welcome from our Symposium Committee! First, we want to acknowledge and pay respect to the Coast Salish peoples whose traditional territory our event is normally held on at the University of Washington’s wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ Intellectual House. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to come together last year but we are so grateful to be able to reunite this year in a safe virtual format. We appreciate the patience of this community and our presenters’ collective understanding and we are thrilled to be back. We hope to be able to gather in person in 2022. We are also very pleased you can join us today for our 9th annual “Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ” Indigenous Foods Symposium. This event brings together individuals to share their knowledge and expertise on topics such as Indigenous foodways and ecological knowledge, Tribal food sovereignty and security initiatives, traditional foods/medicines and health/wellness, environmental justice, treaty rights, and climate change. Our planning committee is composed of Indigenous women who represent interdisciplinary academic fields of study and philanthropy and we volunteer our time to host this annual symposium. We are committed to Indigenous food, environmental, and social justice and recognize the need to maintain a community-based event as we all carry on this important work. We host this event and will continue to utilize future symposia to better serve our Indigenous communities as we continue to foster dialogue and build collaborative networks to sustain our cultural food practices and preserve our healthy relationships with the land, water, and all living things. -

Te Runanga 0 Ngai Tahu Traditional Role of the Rona!Sa

:I: Mouru Pasco Maaka, who told him he was the last Maaka. In reply ::I: William told Aritaku that he had an unmerried sister Ani, m (nee Haberfield, also Metzger) in Murihiku. Ani and Aritaku met and went on to marry. m They established themselves in the area of Waimarama -0 and went on to have many children. -a o Mouru attended Greenhills Primary School and o ::D then moved on to Southland Girls' High School. She ::D showed academic ability and wanted to be a journalist, o but eventually ended up developing photographs. The o -a advantage of that was that today we have heaps of -a beautiful photos of our tlpuna which we regard as o priceless taolsa. o ::D Mouru went on to marry Nicholas James Metzger ::D in 1932. Nick's grandfather was German but was o educated in England before coming to New Zealand. o » Their first son, Nicholas Graham "Tiny" was born the year » they were married. Another child did not follow until 1943. -I , around home and relished the responsibility. She Mouru had had her hopes pinned on a dainty little girl 2S attended Raetihi School and later was a boarder at but instead she gave birth to a 13lb 40z boy called Gary " James. Turakina Maori Girls' College in Marton. She learnt the teachings of both the Ratana and Methodist churches. Mouru went to her family's tlU island Pikomamaku In 1944 Ruruhira took up a position at Te Rahui nui almost every season of her life. She excelled at Wahine Methodist Hostel for Maori girls in Hamilton cooking - the priest at her funeral remarked that "she founded by Princess Te Puea Herangi. -

Te Aroha Domain Reserve Management Plan

1 Acknowledgements: This Management Plan was put together with considerable assistance from the following groups and individuals: Target Te Aroha and Future Te Aroha, Te Aroha and District Museum Society, Te Aroha Business Association, Te Aroha Croquet Club, Te Aroha Community Board, Ngati Tumutumu, Councillors Len Booten and Jan Barnes, and Community Facilities Manager John De Luca of the Matamata Piako District Council. The majority of historical and background information is derived directly from the 1994 Te Aroha Domain Management Plan compiled by Goode Couch and Christie. Particular thanks extended to Antony Matthews for supplying original historic photographs and written material. Landscape plans prepared by Priest Mansergh Graham Landscape Architects Ltd, Hamilton. Edited by Catherine Alington, Redact Technical Writing, Wellington. Prepared for Matamata Piako District Council By Gavin Lister and Kara Maresca of Isthmus Group Ltd Landscape Architects under the direction of John De Luca 2 Te Aroha Domain Management Plan May 2006 Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................7 SECTION ONE..........................................................................................................8 1 ADMINISTRATION AND MANAGEMENT..........................................................8 1.1 Legal Description, Classifications and Administration........................................................ 8 1.2 Administrative History ............................................................................................................ -

Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045

Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045 February 2015 Report prepared by: for: Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045 Quality Assurance Statement Rationale Limited Project Director: Tom Lucas 5 Arrow Lane Project Manager: Walter Clarke PO Box 226 Arrowtown 9302 Prepared by: Walter Clarke New Zealand Approved for issue by: Tom Lucas Phone/Fax: +64 3 442 1156 Document Control G: \1 - Local Government\Thames_Coromandel\01 - Growth Study\2013\MPDC\Urban Analysis\MPDC Detailed Growth Projections to 2045_Final.docx Version Date Revision Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 1 23/12/14 Draft for Client JS WC WC 2 03/02/15 Final WC WC WC MATAMATA-PIAKO DISTRICT COUNCIL STATUS: FINAL 03 FEBRUARY 2015 REV 2 PAGE 2 Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Dwellings .................................................................................................................................... 6 3 Results ............................................................................................................................................... -

The New Zealand Gazette 781

JUNE 28] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 781 MILITARY AREA No. 2 (PAEROA)-oontVlllUed MILITARY AREA No. 2 (PAEROA)-contVlllUed 652176 Clements, Ber.nard Leslie, farm hand, Kutarere, Bay of 647905 Grant, John Gordon, farm hand, c/o W. Grant, P.O., Plenty. Tauranga. 653820 Cochrane, John Gordon, farm hand, Kereone, Morrinsville. 649417 Green, Eric Raymond, farm hand, Matatoki, Thames. 650235 Collins, George Thomas, factory hand, Stanley Rd., Te Aroha. 648437 Griffin, Ivan Ray, farm hand, Richmond Downs, Walton. 651327 Collins, John Frederick, farm hand, c/o P. and T. O'Grady, 654935 Griffin, Robert William, farm hand, Rangiuru Rd., Te Puke. Omokoroa R.D., Tauranga. 649020 Guernier, Frederick Maurice Alfred, vulcanizer, Stanley Rd., 649338 Cooney, Douglas John, farm hand, c/o J. E. Martin, Te Aroha. Ngongotaha. 654323 Haigh, Athol Murry, farm hand, R.D., Gordon, Te Aroha. 654686 Cooper, Leslie John, Waikino. 650227 Hamilton, Anthony Graeme, farm hand, Te Poi R.D., 655006 Cooper, Sefton Aubrey, seaman, 160 Devonport Rd., Matamata. Tauranga. 647964 Hamilton, Donald Cameron, farmer, c/o N. Q. H. Howie, 650435 Corbett, Allen Dale, Totmans Rd., Okoroire, Tirau. Kiwitahi, Morrinsville. 648452 Costello, William Charles, timber-worker, Clayton Rd., 649782 Hammond, David St. George, farm hand, Wiltsdown R.D., Rotorua. No. 2, Putaruru. 653108 Cowley, James Frederick, farm hand, Shaftesbury, Te Aroha. 449888 Handley, Stuart Alley, farm hand, Mill Rd. 655008 Cox, Robert Earle, student, Pollen St., Thames. 650384 Hansen, Leo Noel, dairy factory employee, Hill St., 649340 Craig, Preston Bryce, farm hand, c/o Box 129, Opotiki. 653879 Harrison, Wilfrid Russell, tractor-driver, Hoe-o-Tainui R.D., 650243 Cranston, Blake, farm hand, c/o P. -

TE AROHA in the 1890S Philip Hart

TE AROHA IN THE 1890s Philip Hart Te Aroha Mining District Working Papers No. 115 2016 Historical Research Unit Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton, New Zealand ISSN: 2463-6266 © 2016 Philip Hart Contact: [email protected] 1 TE AROHA IN THE 1890s Abstract: During the 1890s the town slowly increased in size and became economically stronger despite mining, for most of this decade, no longer flourishing. Other occupations became more important, with farming and tending to the needs of tourists being pre-eminent. Residents continued to grumble over the need for improvements, the cost of housing, high rents, and a poor system of tenure, but the establishment of a borough meant that some more improvements could be provided. As the town developed the poor- quality buildings hastily erected in its early days were seen as disfiguring it, and gradually the streets and footpaths were improved. As previously, storms and fires were notable experiences, the latter revealing the need for a water supply and fire fighting equipment. And also as previously, there were many ways to enliven small town life in mostly respectable ways, notably the library, clubs, sports, horse racing, the Volunteers, and entertainments of all kinds, details of which illustrate the texture of social life. Despite disparaging remarks by outsiders, living at Te Aroha need not be as dull as was claimed. POPULATION The census taken on 5 April 1891 recorded 615 residents, 307 males and 308 females, in the town district.1 The electoral roll of June revealed that miners remained the largest group: 19, plus two mine managers. -

Ngāti Hinerangi Deed of Settlement

Ngāti Hinerangi Deed of Settlement Our package to be ratified by you Crown Offer u Commercial Redress u $8.1 million u 5 commercial properties u 52 right of first refusals u Cultural Redress u 14 DOC and Council properties to be held as reserves or unencumbered u 1 overlay classification u 2 deeds of recognition u 11 statutory acknowledgements u Letters of introduction/recognition, protocols, advisory mechanisms and relationship agreements u 1 co-governance position for Waihou River. Commercial Redress u $8.1m Quantum (Cash) u Subject to any purchase of 5 Commercial Properties u Manawaru School Site, Manawaru u Part Waihou Crown Forest Lease (Southern portion) Manawaru u 9 Inaka Place, Matamata u 11 Arawa St, Matamata u Matamata Police Station (Land only) u 52 Right of First Refusals u Te Poi School, Te Poi (MOE) u Matamata College (MOE) u Matamata Primary (MOE) u Omokoroa Point School (MOE) u Te Weraiti (LINZ) u 47 HNZC Properties Cultural Redress u Historical Account u Crown Apology and Acknowledgements u DoC Properties u Te Ara O Maurihoro Historical Reserves (East and West) (Thompsons Track) u Ngā Tamāhine e Rua Scenic Reserve (Pt Maurihoro Scenic Reserve) u Te Tuhi Track (East and West) (Kaimai Mamaku Conservation Park) u Te Taiaha a Tangata Historical Reserve (Whenua-a-Kura) u Waipapa Scenic Reserve(Part Waipapa River Scenic Reserve) u Te Hanga Scenic Reserve (Kaimai Mamaku conservation Park) u Te Mimiha o Tuwhanga Scenic Reserve(Tuwhanga) u Te Wai o Ngati Hinerangi Scenic Reserve (Te Wai o Ngaumuwahine 2) u Ngati Hinerangi Recreational Reserve (Waihou R. -

The Te Aroha Battery, Erected in 1881

THE TE AROHA BATTERY, ERECTED IN 1881 Philip Hart Te Aroha Mining District Working Papers No. 72 2016 Historical Research Unit Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton, New Zealand ISSN: 2463-6266 © 2016 Philip Hart Contact: [email protected] 1 THE TE AROHA BATTERY, ERECTED IN 1881 Abstract: As a local battery was a basic requirement for the field, after some proposals came to nothing a meeting held in January 1881 agreed to form a company to erect and operate one. Although prominent members of the new field were elected as provisional directors, raising capital was a slow process, as many potential investors feared to lose their investments. Once two-thirds of the capital was raised, the Te Aroha Quartz Crushing Company, formed in February, was registered in April. Its shareholders came from a wide area and had very varied occupations. A reconditioned battery, erected in what would become Boundary Street in Te Aroha, was opened with much festivity and optimism in April. It was handicapped by a lack of roads from the mines and insufficient water power, and when the first crushing made the poverty of the ore very apparent it closed after working for only two months. Being such a bad investment, shareholders were reluctant to pay calls. Sold in 1883 but not used, after being sold again in 1888 its machinery was removed; the building itself was destroyed in the following year in one of Te Aroha’s many gales. PLANNING TO ERECT A BATTERY Without a local battery, testing and treating ore was difficult and expensive, and the success or otherwise of the goldfield remained unknown. -

Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Annual Report 2020 Nga Rarangi Take

Nga Rarangi Take Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Annual Report 2020 Nga Rarangi Take Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi When the old net is cast aside, the new net goes fishing, our new strategy remains founded on our vision. Nga Rarangi Take CONTENTS Nga Rarangi Take Introduction/Snapshot 4 Te Arawa 500 scholarships 26 Highlights - 2020 5 Iwi Partnership Grants Programme 27 Your Te Arawa Fisheries 6 Te Arawa Mahi 28 Our Mission/Vision 8 INDIGI-X 29 Message form the Chair 9 Looking to the Future 30 CEO’s Report 10 Research and Development 31 COVID-19 11 Smart Māori Aquaculture Ngā Iwi i Te Rohe o Te Waiariki 32 Rotorua Business Awards Finalist 12 Ka Pu Te Ruha, Ka Hao te Rangatahi Taking our Strategy to the next level 14 Te Arawa Fisheries Climate Change Strategy 34 Governance Development 16 Aka Rākau Strategic Partnerships and Investing for the Future 18 Te Arawa Carbon Forestry Offset Programme 36 Te Arawa Fresh - What Lies Beneath 20 Te Arawa Fresh Online 21 APPENDIX 1: T500 Recipients 38 Our People 22 APPENDIX 2: 2019-2020 Pataka Kai Recipients 40 Our Team 22 APPENDIX 3: AGM Minutes of the Meeting for Te Arawa Fisheries 42 Diversity Report 24 Financial Report 2020 45 Our board of trustees: from left to right. Tangihaere MacFarlane (Ngati Rangiwewehi), Christopher Clarke (Ngati Rangitihi), Blanche Reweti (Ngati Tahu/Whaoa), Dr Kenneth Kennedy (Ngati Rangiteaorere), back Willie Emery (Ngati Pikiao), in front of Dr Ken Roku Mihinui (Tuhourangi), Paeraro Awhimate (Ngati makino), in front Pauline Tangohau (Te Ure o Uenukukopako), behind Punohu McCausland (Waitaha), Tere Malcolm (Tarawhai) Nga Rarangi Take Introduction/Snapshot Timatanga Korero e Kotahitanga o Te Arawa Waka Fisheries Trust Board was legally established on T19 December 1995 by a deed of trust. -

Council Agenda - 26-08-20 Page 99

Council Agenda - 26-08-20 Page 99 Project Number: 2-69411.00 Hauraki Rail Trail Enhancement Strategy • Identify and develop local township recreational loop opportunities to encourage short trips and wider regional loop routes for longer excursions. • Promote facilities that will make the Trail more comfortable for a range of users (e.g. rest areas, lookout points able to accommodate stops without blocking the trail, shelters that provide protection from the elements, drinking water sources); • Develop rest area, picnic and other leisure facilities to help the Trail achieve its full potential in terms of environmental, economic, and public health benefits; • Promote the design of physical elements that give the network and each of the five Sections a distinct identity through context sensitive design; • Utilise sculptural art, digital platforms, interpretive signage and planting to reflect each section’s own specific visual identity; • Develop a design suite of coordinated physical elements, materials, finishes and colours that are compatible with the surrounding landscape context; • Ensure physical design elements and objects relate to one another and the scale of their setting; • Ensure amenity areas co-locate a set of facilities (such as toilets and seats and shelters), interpretive information, and signage; • Consider the placement of emergency collection points (e.g. by helicopter or vehicle) and identify these for users and emergency services; and • Ensure design elements are simple, timeless, easily replicated, and minimise visual clutter. The design of signage and furniture should be standardised and installed as a consistent design suite across the Trail network. Small design modifications and tweaks can be made to the suite for each Section using unique graphics on signage, different colours, patterns and motifs that identifies the unique character for individual Sections along the Trail. -

The Waikato-Tainui Settlement Act: a New High-Water Mark for Natural Resources Co-Management

Notes & Comments The Waikato-Tainui Settlement Act: A New High-Water Mark for Natural Resources Co-management Jeremy Baker “[I]f we care for the River, the River will continue to sustain the people.” —The Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 165 II. THE EMERGENCE OF ADAPTIVE CO-MANAGEMENT ......................... 166 A. Co-management .................................................................... 166 B. Adaptive Management .......................................................... 168 C. Fusion: Adaptive Co-management ....................................... 169 D. Some Criticisms and Challenges Associated with Adaptive Co-management .................................................... 170 III. NEW ZEALAND’S WAIKATO-TAINUI SETTLEMENT ACT 2010—HISTORY AND BACKGROUND ...................................... 174 A. Maori Worldview and Environmental Ethics ....................... 175 B. British Colonization of Aotearoa New Zealand and Maori Interests in Natural Resources ............................ 176 C. The Waikato River and Its People ........................................ 182 D. The Waikato River Settlement Act 2010 .............................. 185 Jeremy Baker is a 2013 J.D. candidate at the University of Colorado Law School. 164 Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y [Vol. 24:1 IV. THE WAIKATO-TAINUI SETTLEMENT ACT AS ADAPTIVE CO-MANAGEMENT .......................................................................... -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

2880 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. llO 118663 Brocklehurst, Frank; Farm Hand, Waitakaruru. 272237 Cameron, Thomas Murray; Pig-farmer, care of C.. N; Walton, 295426 Brockelsby, Charles Kempe, Post-office, Hinuera. Rural :M:ail Delivery, Whakatane. 294599 Brooke; Charles Lee, Farm Hand, Eastport Rd, Waihou, 426279 Campbell, Donald George, Farmer,. Otakiri, Whakatane. Te Aroha. 251841 Campbell, Gor.don Oliver,.Grocery Assistant, care of Wallace 018942 Brooking, Ronald Ernest, Miner, care of Mrs. Stewart, Supplies, Matamata. · 80 Kenny St, Waihi. 240952 Campbell, Ivan Hill, Painter, 40 Tenth Avenue, Tauranga. 281351 Brooks, Edward Lester, Post-splitter, care of Post-office, 231317 Campbell, James Alexander, Orderman, Arahlwi Rd, Mokai. Mamaku. 097779.Brophy, Daniel James, Farmer, Otakiri, Bay of Plenty. 292963 Campbell, Robert, Kauri Point, Katikati. 295423 Brown, Christopher Oaksford (Jun.), Farm Labourer, care 426635 Campbell, William McKenzie, Salesman, Otahiri Rural · of·Mr. G. Miller, Ngarua, Waitoa. Delivery, Whakatane. 422712 Brown, Ernest Edward, Farmer, Matatoki Rd, :M:atatoki. 276825 Cannell, Robert Lewis, Grocer's Assistant, Katikati. 375971 Brown, Louis James Durieu, Farmer, Tauhei, Morrinsville. 191217 Qannell, Thomas Arthur, Exchange Clerk, Katikati. 236054 Brown, Roland, Driller, 90 Brown St, Thames, 236060 Cardno, Colin Grierson, Cheesemaker, care of New Zealand 236058 Brown; Stanley Edwin, Shop-assistant, care of Mr. S. Ensor, co:op. Dairy Co., Ltd., Hikutaia. Mackay St, Thames. 268932 Carlyle, George Leonard, Share-milker, Okoroire. 283255 Brown Thomas, Dairyman, Waharoa. 423298 Carmichael, Cyril Gordon, Dairy-farmer, Bethlehem Rural 054439 Brown, William, Farmer, Tatuanui. Delivery, Tauranga. 167837 Brown, William Graham, Labourer, care of. Grande Vue ·265032 Carr, James Harry, Butcher, Tanding Rd, Whakatane. Private Hotel, Whakatane.