Tadao Ando Kenneth Frampton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renzo Piano Designs a Reverent Addition to Louis Kahn's Kimbell

SEEMING INEVITABILITY: renzo piano designs a reverent addition to louis kahn’s kimbell 6 spring INEVITABILITY: Lef: Aerial view from northwest. Above: Piano Pavilion from east, 2014. Photos: Michel Denancé. by ronnie self Louis Kahn’s and Renzo Piano’s buildings for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth are mature projects realized by septuagenarian architects. They show a certain wis- dom that may come with age. As a practitioner, Louis Kahn is generally considered a late bloomer. His most respected works came relative- ly late in his career, and the Kimbell, which opened a year and a half before his death, is among his very best. Many of Kahn’s insights came through reflection in parallel to practice, and his pursuits to reconcile modern architec- ture with traditions of the past were realized within his own, individual designs. spring 7 Piano (along with Richard Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini) won the competition for the Centre Pompidou in Paris as a young architect piano’s main task was to respond appropriately only in his mid-30s. Piano sees himself as a “builder” and his insights come largely through experience. Aside from the more famboyant Cen- to kahn’s building, which he achieved through tre in the French capital, Piano was entrusted relatively early in his career with highly sensitive projects in such places as Malta, Rhodes, alignments in plan and elevation ... and Pompeii. He made studies for interventions to Palladio’s basilica in Vicenza. More recently he has been called upon to design additions to modern architectural monuments such as Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Mu- seum of American Art in New York and Le Corbusier’s chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp. -

Contemporary Itinerary

contemporary itinerary Japan edited by Sara Dello Scarparo, Andrea Ferraro 16:0916:096:09 contemporary itinerary: Japan 04 1 3 2 5 4 6 03 A gojo dori 1 Kyoto 4 Awaji nishi-gojo dori 01. Kyoto station, Hirishi Hara 32. Yumebutai, Tadao Ando 02. Villa Katsura 33. Water temple, Tadao Ando 03. Bamboo Forest 34. House on Awaji island, Izue san-in road 02 04. Kinkaku-Ji temple Architects 05. Higashi Honganji reception hall, kujo dori Shin Takamatsu 5 Naoshima 06. Grand Blue Saniyo Yanaginobanba, Skin Takamatsu 35. Naoshima boat terminal, SANAA 07. Bake Cheese Tart Store, Yusuke Seki 36. Naoshima bath, Shinro Ohtake 08. Today‘s Special, Schemata 37. Naoshima pavillion, Sou Fujimot 1 Architects 38. Chi-chu art museum, Tadao Ando 09. Times Building, Tadao Ando 39. Lee Ufan museum, Tadao Ando 10. Garden of Fine Art, Tadao Ando 40. Benesse house, Tadao Ando 3 11. Kyoto Concert Hall, Arata Isozaki 41. Benesse hotel, Tadao Ando 12. National Museum of Modern Art, 42. Minamidera house, Tadao Ando Fumihiko Maki 43. Naoshima hall, Sambuichi 13. Fujimi Inary Architects 44. Kadoya house, Tadashi Yamamoto 2 Osaka 6 Teshima 14. Rolex Nakatsu Building, Fumihiko Maki 45. Teshima Yokoo house, Yuko 15. Expo Tower, Kiyonori Kikutake Nagayama 16. Sun Tower, Taro Okamoto 46. Restaurant on the sea, Koichi 17. Light Church, Tadao Ando Futatsumata 18. Umeda Sky Building, Hiroshi Hara 47. Shima kitche, Atelier Ryo Abe 19. Tomishima house, Tadao Ando 48. Teshima art museum, SANAA 20. TS Building, Tadao Ando 21. Akka gallery, Tadao Ando 22. Osaka dome, Nikken Sekkei 23. -

Introducing Tokyo Page 10 Panorama Views

Introducing Tokyo page 10 Panorama views: Tokyo from above 10 A Wonderful Catastrophe Ulf Meyer 34 The Informational World City Botond Bognar 42 Bunkyo-ku page 50 001 Saint Mary's Cathedral Kenzo Tange 002 Memorial Park for the Tokyo War Dead Takefumi Aida 003 Century Tower Norman Foster 004 Tokyo Dome Nikken Sekkei/Takenaka Corporation 005 Headquarters Building of the University of Tokyo Kenzo Tange 006 Technica House Takenaka Corporation 007 Tokyo Dome Hotel Kenzo Tange Chiyoda-ku page 56 008 DN Tower 21 Kevin Roche/John Dinkebo 009 Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka Kenzo Tange 010 Metro Tour/Edoken Office Building Atsushi Kitagawara 011 Athénée Français Takamasa Yoshizaka 012 National Theatre Hiroyuki Iwamoto 013 Imperial Theatre Yoshiro Taniguchi/Mitsubishi Architectural Office 014 National Showa Memorial Museum/Showa-kan Kiyonori Kikutake 015 Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance Company Building Kunio Maekawa 016 Wacoal Building Kisho Kurokawa 017 Pacific Century Place Nikken Sekkei 018 National Museum for Modern Art Yoshiro Taniguchi 019 National Diet Library and Annex Kunio Maekawa 020 Mizuho Corporate Bank Building Togo Murano 021 AKS Building Takenaka Corporation 022 Nippon Budokan Mamoru Yamada 023 Nikken Sekkei Tokyo Building Nikken Sekkei 024 Koizumi Building Peter Eisenman/Kojiro Kitayama 025 Supreme Court Shinichi Okada 026 Iidabashi Subway Station Makoto Sei Watanabe 027 Mizuho Bank Head Office Building Yoshinobu Ashihara 028 Tokyo Sankei Building Takenaka Corporation 029 Palace Side Building Nikken Sekkei 030 Nissei Theatre and Administration Building for the Nihon Seimei-Insurance Co. Murano & Mori 031 55 Building, Hosei University Hiroshi Oe 032 Kasumigaseki Building Yamashita Sekkei 033 Mitsui Marine and Fire Insurance Building Nikken Sekkei 034 Tajima Building Michael Graves Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1010431374 Chuo-ku page 74 035 Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki Store Jun Aoki 036 Gucci Ginza James Carpenter 037 Daigaku Megane Building Atsushi Kitagawara 038 Yaesu Bookshop Kajima Design 039 The Japan P.E.N. -

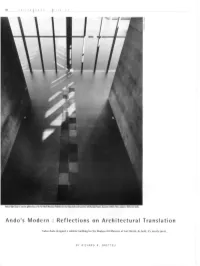

Ando's Modern : Reflections on Architectural Translation

24 J p i > n g [ioI 2 u InI i I C i I e 17 Nolurol light floods a concrete gallery bay in the Fort Worth Museum of Modern Art, by Tadao Anda and Associates wilh Kendall/Heaton Associates (2002). Floor sculpture: Slil by Carl Andre. Ando's Modern : Reflections on Architectural Translation Tadao Ando designed a sublime building for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. As built, it's merely great. BY RICHARD R. BRETTELL Cite 5 7 2 o o 11 5 p r i n g 25 Tadoo Ando's (ompelilion mode! showed eight lucite lozenges floating on o blue reflective surface. Ando's competition rendering revealed a light filtering roof, intended lo be realized in glass and steel. The Competition and Ando's Ando's competition model was a Winning Entry series of eight gorgeous lucite lozenges In 1996, the architectural review commit- (lour ol which were connected longitudi- I tee lor the Modern chose sis architects to nally in pairs to form six bays), floating I compete: two Japanese ("Fadao Ando and on a blue reflective surface. Its shimmer- J Arata Iso/aki), one Mexican (Ricardo ing ambiguities ol surface combined with I 1 cgoretta), and three Americans (Richard us lucid geometry to be utterly com- Gluclctnan, Carlos Jimenez, and David pelling, and most viewers of the model Schwarz). Why llns bouquet? File most attempted to "visualize" it as an actual unusual aspect of the selection was how building with little success. Ando's basic relatively non-trendy ir was — no fashion idea was a museum of parallel two-story r;_ —_ v—I- • able Europeans, DO chic Americans, no concrete galleries. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Top Japanese Architects

TOP JAPANESE ARCHITECTS CURRENT VIEW OF JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE by Judit Taberna To be able to understand modern Japanese architecture we must put it into its historic context, and be aware of the great changes the country has undergone. Japan is an ancient and traditional society and a modern society at the same time. The explanation for this contradiction lies in the rapid changes resulting from the industrial and urban revolutions which began in Japan in the Meiji period and continued with renewed force in the years after the second world war. At the end of the nineteenth century, during the Meiji period, the isolation of the country which had lasted almost two centuries came abruptly to an end; it was the beginning of a new era for the Japanese who began to open up to the world. They began to study European and American politics and culture. Many Japanese architects traveled to Europe and America, and this led to the trend of European modernism which soon became a significant influence on Japanese architecture. With the Second World War the development in modern Japanese architecture ground to a halt, and it was not until a number of years later that the evolution continued. Maekawa and Sakura, the most well known architects at the time, worked with Le Corbusier and succeeded in combining traditional Japanese styles with modern architecture. However Kenzo Tange, Maekawa's disciple, is thought to have taken the first step in the modern Japanese movement. The Peace Center Memorial Museum at Hiroshima 1956, is where we can best appreciate his work. -

The Great Living Creative Spirit

The Great Living Creative Spirit Frank LLoyd Wright s legacy in japan Soib ' SS NoV. ii– . Join the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy for a specially curated tour highlighting modern and contemporary architecture FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT by Wright, Arata Endo, Antonin Raymond, Le Corbusier, Tadao BUILDING CONSERVANCY Ando, Kenzo Tange, Toyo Ito, Kengo Kuma and many more. Day one Sunday, Nov. 11 Arrive in Tokyo and check in at the Imperial Hotel (flights and hotel transfer not included). In the early evening, meet the rest of the group (limited to 27) for a welcome dinner at the historic For- MORI eign Correspondents‘ Club of Japan and a viewing of the Rafael Viñoly-designed Tokyo International Forum. Later, take an optional OICHI evening walking tour of Ginza, the famous upscale shopping and © K entertainment district where the traditional and modern meet. HOTO Overnight: Imperial Hotel, Tokyo / Meals: Dinner P Day TWO Monday, Nov. 12 The first full day begins with a tour of the 1970 Imperial Hotel, which includes the Old Imperial Bar, outfitted with relics of Wright’s demolished Imperial Hotel (1923-67). Then journey to Meguro St. Anselm’s Church, designed by Antonin Raymond, and have lunch at Meguro Gajoen, a lavish design furnished with artwork from its 1928 origins. Continue with a special visit to the private home Japanese modernist Kunio Maekawa built for himself in 1974, then a walking tour of Omotesando (a broad avenue lined with flagship designs by the likes of SANAA, Toyo Ito, Herzog & de Meuron, Kengo Kuma, Tadao Ando and Kenzo Tange). After a visit to the 21_21 Design Sight museum and gallery, designed by Tadao Ando, we finish the day with a view from the 52nd-floor observation deck at Mori Tower in Roppongi Hills, designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox. -

10 'Land of Kami, Land of the Dead'

10 ‘Land of kami, land of the dead’ ! Paligenesis and the aesthetics of religious revisionism in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s ‘Neo-G!manist Manifesto: On Yasukuni’ ! James Mark Shields ! ! ! ! Figure 10.1 Shin g!manizumu sengen special: Yasukuniron [Neo-G!manism Mani- 1 festo Special: On Yasukuni], p. 12. ! Manga is an art that should warn of or actively attack all things in the world that are unjust, irrational, unnatural, or incongruous with the will of the nation. Kat! Etsur!, Shin rinen manga no gih! [Techniques for a New Manga], 1942 ! Yasukuni Shrine is the final stronghold in defence of the history, spirit, and culture of Japan. Kobayashi Yoshinori, Yasukuniron, 2005, 68 ! In 1992, just as Japan’s economic bubble was in process of bursting, a series of manga began to appear in the weekly Japanese tabloid SPA! under the title G!manism sengen (Haughtiness or Insolence Manifesto). Authored by Kobayashi Yoshinori (b. 1953), this series blurs the line between manga and graphic novel2 to engage in forthright social and political commentary with an unabashedly (ultra-)nationalistic slant. Over the next decade and a half, Kobayashi and his works became a publishing ! 190James Mark Shields ! phenomenon. As of 2010, there were over 30 volumes of G!manism (and Neo-G!manism) manga, including several ‘special editions’ – such as the best- selling Shin g!manizumu sengen special: Sens!ron (Neo-G!manism Manifesto Special: On War, 1998) – that have caused controversy and even international criti- cism for their revisionist portrayal of modern Japanese history.3 At its most general, Neo-G!manism is a graphic ‘style’ marked by withering sarcasm and blustering anger at what is perceived as Japanese capitulation to the West and China on matters of foreign policy and the treatment of recent East Asian history. -

Haute Concrete with His First Building in New York, the Architect Tadao Ando Takes the Material to New Heights

Haute Concrete With his first building in New York, the architect Tadao Ando takes the material to new heights. BIANCA BOSKER APRIL 2017 ISSUE 4 hile architects once worker ash a cigarette into the considered concrete a 1 concrete mixture for one of Ando’s Wbuilding’s underwear— buildings, he reportedly slugged an essential but hidden layer— the man. Tadao Ando’s 1 1 structures display Over the course of his nearly their concrete with pride. There’s a 50-year career, Ando has helped story (which Ando’s team declined transform the gritty, gray material to confirm) that’s used to illustrate often associated with driveways how seriously Ando takes the and median strips into an artistic material: When the architect, a medium. “Every architect I know former boxer, saw a construction who wants to do something in 2 3 concrete always refers to him as the ideal in concrete design,” says Reg Hough, a concrete consultant who has for decades worked closely with top architects, including Ando, I. M. Pei, and Richard Meier. Having left his mark on cities from Tokyo to Fort Worth to Milan, Ando is now overseeing construction of a seven-unit, concrete-and- glass condominium building, 152 Elizabeth 2 3 , his first stand- depressions 4. 4 (It’s even possible so, nine inspectors oversee most alone structure in New York City. to buy premade paneling that pours to ensure that every protocol Ando is hardly the first knocks off the Ando look.) When is followed. The crew has lugged architect to embrace concrete; 152 Elizabeth is completed later in heaters, because concrete is he cites the brutalist architect this year, its apartments will feature hypersensitive to temperature Le Corbusier, an earlier concrete Ando’s concrete both inside and shifts. -

About Religion in Japan

CK_5_TH_HG_P104_230.QXD 2/14/06 2:23 PM Page 225 The samurai developed a code of ethics known as Bushido, the way of the warrior. According to Bushido, samurai were to be frugal, incorruptible, brave, Teaching Idea self-sacrificing, loyal to their lords, and above all, courageous. It was considered Research groups that have codes of better to commit ritual suicide than to live in dishonor. In time, Zen Buddhism ethics, and compare Bushido to these influenced the samurai code, and self-discipline and self-restraint became two other codes. Restate the “code of important virtues for samurai to master. 45 ethics” for the class, and possibly develop a code of ethics for the class Japan Closed to Outsiders during this unit of study. From 1603 to 1867, the Tokugawa Shogunate ruled Japan. Early in the dynasty, the shogun closed off Japan from most of the rest of the world and reasserted feudal control, which had been loosening. In the 1500s, the first Teaching Idea European traders and missionaries had visited the island nation and brought with Teach students about samurai by them new ideas. Fearing that further contact would weaken their hold on the gov- reading fictional samurai stories. See ernment and the people, the Tokugawa banned virtually all foreigners. One Dutch More Resources for suggestions. ship was allowed to land at Nagasaki once a year to trade. The ban was not limited to Europeans. Only a few Chinese a year were allowed to enter Japan for trading purposes. In addition, the Japanese themselves were not allowed to travel abroad for any reason. -

Ando in the Context of Critical Regionalism

Concrete Resistance: Ando in the context of critical regionalism Xianghua Wu 48-341: History of Architectural Theory Professor Kai Gutschow 10 May 2006 Critical regionalism was first introduced as an architectural concept in the early 1980s in essays by Alexander Tzonis, Liane Lefaivre and, subsequently, Kenneth Frampton. In his writings, Frampton mentions and celebrates Tadao Ando as a critical regionalist, and uses the approach as a paradigm to discuss Ando’s architecture. 1 Yet despite the label, Ando has neither used the terms “critical regionalism” to talk about his work, nor raised any objection over the label. It is also important to note that Tadao Ando is not mentioned in Frampton’s original article on critical regionalism, “Towards a Critical Regionalism.” 2 Thus, is “critical regionalist” an appropriate term to describe Ando’s architecture? Catherine Slessor posits an alternative label, “concrete regionalist,” to describe Ando’s poetic adaptation of concrete to the local context, thus playing down the “critical” aspect of his approach. 3 Is “concrete regionalist” a more accurate description of Ando’s work? This paper shall demonstrate that while Ando’s architecture does display some characteristics of critical regionalism, he is not strictly “critical regionalist” if we are to follow its definition as described by Tzonis, Liane, and Frampton. This paper will start by providing background on the evolution of critical regionalism, examining arguments of how Ando’s approach is “critical regionalist,” and finally demonstrating the inadequacy of the label by breaking down these arguments. The concept of regionalism is nothing new; Vitruvius discussed regional variations in architecture in his ten books, and the Romantics propounded picturesque regionalism during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.