University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renzo Piano Designs a Reverent Addition to Louis Kahn's Kimbell

SEEMING INEVITABILITY: renzo piano designs a reverent addition to louis kahn’s kimbell 6 spring INEVITABILITY: Lef: Aerial view from northwest. Above: Piano Pavilion from east, 2014. Photos: Michel Denancé. by ronnie self Louis Kahn’s and Renzo Piano’s buildings for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth are mature projects realized by septuagenarian architects. They show a certain wis- dom that may come with age. As a practitioner, Louis Kahn is generally considered a late bloomer. His most respected works came relative- ly late in his career, and the Kimbell, which opened a year and a half before his death, is among his very best. Many of Kahn’s insights came through reflection in parallel to practice, and his pursuits to reconcile modern architec- ture with traditions of the past were realized within his own, individual designs. spring 7 Piano (along with Richard Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini) won the competition for the Centre Pompidou in Paris as a young architect piano’s main task was to respond appropriately only in his mid-30s. Piano sees himself as a “builder” and his insights come largely through experience. Aside from the more famboyant Cen- to kahn’s building, which he achieved through tre in the French capital, Piano was entrusted relatively early in his career with highly sensitive projects in such places as Malta, Rhodes, alignments in plan and elevation ... and Pompeii. He made studies for interventions to Palladio’s basilica in Vicenza. More recently he has been called upon to design additions to modern architectural monuments such as Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Mu- seum of American Art in New York and Le Corbusier’s chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp. -

Contemporary Itinerary

contemporary itinerary Japan edited by Sara Dello Scarparo, Andrea Ferraro 16:0916:096:09 contemporary itinerary: Japan 04 1 3 2 5 4 6 03 A gojo dori 1 Kyoto 4 Awaji nishi-gojo dori 01. Kyoto station, Hirishi Hara 32. Yumebutai, Tadao Ando 02. Villa Katsura 33. Water temple, Tadao Ando 03. Bamboo Forest 34. House on Awaji island, Izue san-in road 02 04. Kinkaku-Ji temple Architects 05. Higashi Honganji reception hall, kujo dori Shin Takamatsu 5 Naoshima 06. Grand Blue Saniyo Yanaginobanba, Skin Takamatsu 35. Naoshima boat terminal, SANAA 07. Bake Cheese Tart Store, Yusuke Seki 36. Naoshima bath, Shinro Ohtake 08. Today‘s Special, Schemata 37. Naoshima pavillion, Sou Fujimot 1 Architects 38. Chi-chu art museum, Tadao Ando 09. Times Building, Tadao Ando 39. Lee Ufan museum, Tadao Ando 10. Garden of Fine Art, Tadao Ando 40. Benesse house, Tadao Ando 3 11. Kyoto Concert Hall, Arata Isozaki 41. Benesse hotel, Tadao Ando 12. National Museum of Modern Art, 42. Minamidera house, Tadao Ando Fumihiko Maki 43. Naoshima hall, Sambuichi 13. Fujimi Inary Architects 44. Kadoya house, Tadashi Yamamoto 2 Osaka 6 Teshima 14. Rolex Nakatsu Building, Fumihiko Maki 45. Teshima Yokoo house, Yuko 15. Expo Tower, Kiyonori Kikutake Nagayama 16. Sun Tower, Taro Okamoto 46. Restaurant on the sea, Koichi 17. Light Church, Tadao Ando Futatsumata 18. Umeda Sky Building, Hiroshi Hara 47. Shima kitche, Atelier Ryo Abe 19. Tomishima house, Tadao Ando 48. Teshima art museum, SANAA 20. TS Building, Tadao Ando 21. Akka gallery, Tadao Ando 22. Osaka dome, Nikken Sekkei 23. -

Introducing Tokyo Page 10 Panorama Views

Introducing Tokyo page 10 Panorama views: Tokyo from above 10 A Wonderful Catastrophe Ulf Meyer 34 The Informational World City Botond Bognar 42 Bunkyo-ku page 50 001 Saint Mary's Cathedral Kenzo Tange 002 Memorial Park for the Tokyo War Dead Takefumi Aida 003 Century Tower Norman Foster 004 Tokyo Dome Nikken Sekkei/Takenaka Corporation 005 Headquarters Building of the University of Tokyo Kenzo Tange 006 Technica House Takenaka Corporation 007 Tokyo Dome Hotel Kenzo Tange Chiyoda-ku page 56 008 DN Tower 21 Kevin Roche/John Dinkebo 009 Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka Kenzo Tange 010 Metro Tour/Edoken Office Building Atsushi Kitagawara 011 Athénée Français Takamasa Yoshizaka 012 National Theatre Hiroyuki Iwamoto 013 Imperial Theatre Yoshiro Taniguchi/Mitsubishi Architectural Office 014 National Showa Memorial Museum/Showa-kan Kiyonori Kikutake 015 Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance Company Building Kunio Maekawa 016 Wacoal Building Kisho Kurokawa 017 Pacific Century Place Nikken Sekkei 018 National Museum for Modern Art Yoshiro Taniguchi 019 National Diet Library and Annex Kunio Maekawa 020 Mizuho Corporate Bank Building Togo Murano 021 AKS Building Takenaka Corporation 022 Nippon Budokan Mamoru Yamada 023 Nikken Sekkei Tokyo Building Nikken Sekkei 024 Koizumi Building Peter Eisenman/Kojiro Kitayama 025 Supreme Court Shinichi Okada 026 Iidabashi Subway Station Makoto Sei Watanabe 027 Mizuho Bank Head Office Building Yoshinobu Ashihara 028 Tokyo Sankei Building Takenaka Corporation 029 Palace Side Building Nikken Sekkei 030 Nissei Theatre and Administration Building for the Nihon Seimei-Insurance Co. Murano & Mori 031 55 Building, Hosei University Hiroshi Oe 032 Kasumigaseki Building Yamashita Sekkei 033 Mitsui Marine and Fire Insurance Building Nikken Sekkei 034 Tajima Building Michael Graves Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1010431374 Chuo-ku page 74 035 Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki Store Jun Aoki 036 Gucci Ginza James Carpenter 037 Daigaku Megane Building Atsushi Kitagawara 038 Yaesu Bookshop Kajima Design 039 The Japan P.E.N. -

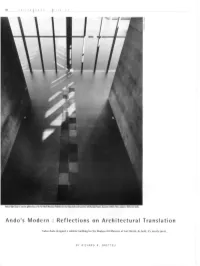

Ando's Modern : Reflections on Architectural Translation

24 J p i > n g [ioI 2 u InI i I C i I e 17 Nolurol light floods a concrete gallery bay in the Fort Worth Museum of Modern Art, by Tadao Anda and Associates wilh Kendall/Heaton Associates (2002). Floor sculpture: Slil by Carl Andre. Ando's Modern : Reflections on Architectural Translation Tadao Ando designed a sublime building for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. As built, it's merely great. BY RICHARD R. BRETTELL Cite 5 7 2 o o 11 5 p r i n g 25 Tadoo Ando's (ompelilion mode! showed eight lucite lozenges floating on o blue reflective surface. Ando's competition rendering revealed a light filtering roof, intended lo be realized in glass and steel. The Competition and Ando's Ando's competition model was a Winning Entry series of eight gorgeous lucite lozenges In 1996, the architectural review commit- (lour ol which were connected longitudi- I tee lor the Modern chose sis architects to nally in pairs to form six bays), floating I compete: two Japanese ("Fadao Ando and on a blue reflective surface. Its shimmer- J Arata Iso/aki), one Mexican (Ricardo ing ambiguities ol surface combined with I 1 cgoretta), and three Americans (Richard us lucid geometry to be utterly com- Gluclctnan, Carlos Jimenez, and David pelling, and most viewers of the model Schwarz). Why llns bouquet? File most attempted to "visualize" it as an actual unusual aspect of the selection was how building with little success. Ando's basic relatively non-trendy ir was — no fashion idea was a museum of parallel two-story r;_ —_ v—I- • able Europeans, DO chic Americans, no concrete galleries. -

The Ethos in the Form Making of Grand Projects in Contemporary Beijing City .Fiotch

The Ethos in the Form Making of Grand Projects in Contemporary Beijing City By Keru Feng Bachelor of Architecture Beijing Polytechnic University, 1999 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2004 @ 2004 Keru Feng All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Department ofArchitecture May 19, 2004 Certif ied by Norman B. and Muriel Leventhal Professor of Architecture and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Julian Beinart Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUJSETTS INS fVTE OF TECHNOLOGY 2004 JUL 0 9 LIBRARIES . FiOTCH THESIS COMMITTEE Thesis Advisor William Porter Norman B. and Muriel Leventhal Professor of Architecture and Planning Thesis Reader Stanford Anderson Professor of History and Architecture; Head, Department of Architecture Thesis Reader Yan Huang Deputy Director of the Beijing Municipal Planning Commission The Ethos in the Form Making of Grand Projects in Contemporary Beijing City By Keru Feng Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 19, 2004 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT Capital cities embody national identity and ethos, buildings in the capital cities have the power to awe and to inspire. While possibly no capital city in the world is being renewed so intensely as Beijing, which presents both enormous potential and threat. Intrinsic to this research is a concept that the design culture of a city is formed largely by the national character, aesthetic value and culture distinctive to that city; these are the soil of design culture which merit careful observation and description. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

GRIGORY MASLENNIKOV " ARCHITECTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS" Architectural Constructions

GRIGORY MASLENNIKOV " ARCHITECTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS" Architectural constructions Architecture is the language of giants, the greatest system of visual elements that was ever created by the humankind. Just like artists, architects are not inclined to talk much, because they are aiming to create tangible objects. Each creative professional has their own tools for communicating their thoughts and feelings. For me, the most complicated yet essential element of architecture and art is simplicity. Simple forms require perfect proportions and measurements that result in visual harmony. To achieve that in my works I experi- ment with texture and colours. It’s not an easy task trying to translate words into construction elements. But being an admirer of archi- tecture myself, I’m setting out on a mission to reimag-ine creations by leading architects of the world in paintings. It’s a complicated yet fascinating challenge. Please join me on my quest powered by imagination and by the artistic tools that will bring it into reality. Painting 1 Ettore Sottsass 170 х 120 cm oil, canvas The painting by the “patriarch of Italian design” is a reflection of his inclina-tion towards simple geome- try, bright colours and playful style. His architec-ture is intimate and is meant for people, not institutions. At its core is the tradi-tionally Medi- terranean approach to life - seizing every moment and enjoying simplicity. Painting 2 Arata Isozaki 170 х 120 cm oil, canvas, metal This work describes Isozaki’s own character. One of the leaders of the 1960s’ avant-garde movement, he learnt from Kenzo Tange and managed to introduce romanticism and humour into large-scale urban construction. -

The Vision of a Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao

HARVARD DESIGN SCHOOL THE VISION OF A GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM IN BILBAO In a March 31, 1999 article, the Washington Post? posed the following question: "Can a single building bring a whole city back to life? More precisely, can a single modern building designed for an abandoned shipyard by a laid-back California architect breath new economic and cultural life into a decaying industri- al city in the Spanish rust belt?" Still, the issues addressed by the article illustrate only a small part of the multifaceted Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao. A thorough study of how this building was conceived and made reveals equally significant aspects such as getting the best from the design architect, the master handling of the project by an inexperienced owner, the pivotal role of the executive architect-project man- ager, the dependence on local expertise for construction, the transformation of the architectural profession by information technology, the budgeting and scheduling of an unprecedented project without sufficient information. By studying these issues, the greater question can be asked: "Can the success of the Guggenheim museum be repeated?" 1 Museum Puts Bilbao Back on Spain’s Economic and Cultural Maps T.R. Reid; The Washington Post; Mar 31, 1999; pg. A.16 Graduate student Stefanos Skylakakis prepared this case under the supervision of Professor Spiro N. Pollalis as the basis for class discussion rather to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation, a design process or a design itself. Copyright © 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to repro- duce materials call (617) 495-4496. -

Eisenman Architects’ Map

1 INTRODUCTION M Matteo Cainer Matteo Cainer is a practising After receiving his master’s degree from the University In 2013 he co-founded and co-directed with Odile of Architecture in Venice, Italy, Matteo worked and Decq the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Office Principal architect, curator and educator. collaborated with a number of celebrated international Creative Strategies in Architecture in Lyon, France Based in London, he is Principal of practices including Peter Eisenman in New York and was Chair and professor until July 2015. City, Coop Himmelb(l)au in Vienna, and Arata Isozaki Matteo Cainer Architecture, founder Associati in Milan. It was in London that he then In March of 2020 to respond to the pandemic he of the Confluence Institute for created/directed the Design Research Studio at launches MCA Online a free educational initiative to Fletcher Priest Architects, and in June 2010 opened provide help and support to home-bound students Innovation and Creative Strategies his own practice. with tutorials, crits and a series of Lectures. He then in Architecture in Lyon, France and launches as part of Alphabet for the Futrure “What Now? Curatorially in 2004 he was Assistant Director to and ‘Post C-19!’ an Open Call to all the Architectural Director of Architecture Whispers. Kurt W. Forster for the 9th International Architecture Graduates of 2020 to imagine and sketch how Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia - METAMORPH, they see and want the future to CHANGE. Matteo and in 2006 was appointed curator of the London continues to be a regular guest critic and jury member Architecture Biennale - CHANGE, with the exhibition: in various universities worldwide. -

Top Japanese Architects

TOP JAPANESE ARCHITECTS CURRENT VIEW OF JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE by Judit Taberna To be able to understand modern Japanese architecture we must put it into its historic context, and be aware of the great changes the country has undergone. Japan is an ancient and traditional society and a modern society at the same time. The explanation for this contradiction lies in the rapid changes resulting from the industrial and urban revolutions which began in Japan in the Meiji period and continued with renewed force in the years after the second world war. At the end of the nineteenth century, during the Meiji period, the isolation of the country which had lasted almost two centuries came abruptly to an end; it was the beginning of a new era for the Japanese who began to open up to the world. They began to study European and American politics and culture. Many Japanese architects traveled to Europe and America, and this led to the trend of European modernism which soon became a significant influence on Japanese architecture. With the Second World War the development in modern Japanese architecture ground to a halt, and it was not until a number of years later that the evolution continued. Maekawa and Sakura, the most well known architects at the time, worked with Le Corbusier and succeeded in combining traditional Japanese styles with modern architecture. However Kenzo Tange, Maekawa's disciple, is thought to have taken the first step in the modern Japanese movement. The Peace Center Memorial Museum at Hiroshima 1956, is where we can best appreciate his work. -

Architecture As a Game, Isozaki in Barcelona

ARCHITECTURE ARCHITECTURE AS A GAME, ISOZAKI IN BARCELONA THEREIS NO DENYING THE GROWING IMPORTANCE OF JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE TODAY. IN ISOZAKI'S APPROACH TO HIS WORK IN THE WEST, HE REMAINS FAITHFUL TO HIS ORIENTALORIGINS THOUGH WITHOUT FORGETTING THE WESTERN WORLD. PAVlllON SANT JORDI. BARCELONA. ARCHITECTURE ARCHITECTURE PAVlLlON SANI JORDI. BARCELONA. ven before the lnternational the construction of the INEF (National nized as the most characteristic devel- Olympic Committee chose Bar- lnstitute for Physical Educationl was as- opment in contemporary Catalan cul- celona to host the summer signed to Ricard Bofill and his Taller ture, and come across Antoni Gaudí and games of 1992, the city felt an over- d'Arquitectura, and finally, the new Pa- his student Josep M. Jujol. From Gaudí whelming need to retrieve the sports lau dlEsports was to be the work of the he has borrowed those structural and precinct for which the stadium had been architect Arata Isozaki. formal elements which leave most room for built, at the end of the twenties, as part Arata lsozaki was born in 1931 in Oita, creativity while at the same time recog- of the development of the mountain of Kyushu, in Japan. He was a favourite nizing their links with Catalan architec- Montjuic. In this way, the "Estadi" and student of Kenzo Tange, with whom he ture. lsozaki wants his work to relate to the "Palau Nacional" became the last worked on the proiects for the 1964 its location, not only by virtue of its two symbols to lose their condition of Olympic Games in Tokyo, in particular formal affinity to Catalan architecture, ephemeral architecture after the Barce- on the Sports Palace in Takamatsu, be- but mainly because he is interested in lona lnternational Exhibition of 1929 tween 1962 and 1964. -

The Great Living Creative Spirit

The Great Living Creative Spirit Frank LLoyd Wright s legacy in japan Soib ' SS NoV. ii– . Join the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy for a specially curated tour highlighting modern and contemporary architecture FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT by Wright, Arata Endo, Antonin Raymond, Le Corbusier, Tadao BUILDING CONSERVANCY Ando, Kenzo Tange, Toyo Ito, Kengo Kuma and many more. Day one Sunday, Nov. 11 Arrive in Tokyo and check in at the Imperial Hotel (flights and hotel transfer not included). In the early evening, meet the rest of the group (limited to 27) for a welcome dinner at the historic For- MORI eign Correspondents‘ Club of Japan and a viewing of the Rafael Viñoly-designed Tokyo International Forum. Later, take an optional OICHI evening walking tour of Ginza, the famous upscale shopping and © K entertainment district where the traditional and modern meet. HOTO Overnight: Imperial Hotel, Tokyo / Meals: Dinner P Day TWO Monday, Nov. 12 The first full day begins with a tour of the 1970 Imperial Hotel, which includes the Old Imperial Bar, outfitted with relics of Wright’s demolished Imperial Hotel (1923-67). Then journey to Meguro St. Anselm’s Church, designed by Antonin Raymond, and have lunch at Meguro Gajoen, a lavish design furnished with artwork from its 1928 origins. Continue with a special visit to the private home Japanese modernist Kunio Maekawa built for himself in 1974, then a walking tour of Omotesando (a broad avenue lined with flagship designs by the likes of SANAA, Toyo Ito, Herzog & de Meuron, Kengo Kuma, Tadao Ando and Kenzo Tange). After a visit to the 21_21 Design Sight museum and gallery, designed by Tadao Ando, we finish the day with a view from the 52nd-floor observation deck at Mori Tower in Roppongi Hills, designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox.