Part in Stimulating Debates and Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A B S T R a C T S

5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting Perspectives on an endangered species A B S T R A C T S EGSM 5 • 5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting • Rust •Austria • 02-05 Oct 2014 • egsm2014.univie.ac.at EGSM 5 5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting Perspectives on an endangered species ABSTRACTS 02‐05 October 2014 • Rust • Burgenland • Austria 5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting Perspectives on an endangered species Published and edited by: Eva Millesi and Ilse E. Hoffmann Department of Behavioural Biology Faculty of Life Sciences University of Vienna, Althanstraße 14 1090 Vienna, Austria http://www.behaviour.univie.ac.at/ The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from them remain the responsibility of the authors. Revision of abstracts: Ilse E. Hoffmann, Werner Haberl Layout: Dagmar Rotter, Ilse E. Hoffmann, Michaela Brenner Cover: Ilse E. Hoffmann Photograph © Lukas Mroz / modified after maps.iucnredlist.org (http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=20472/) Printed by: druck.at, Aredstraße 7, 2544 Leobersdorf, Austria Printed with the support of: Amt der NÖ Landesregierung, Abteilung Naturschutz (RU5) ISBN 978-3-200-03792-2 © 2014 University of Vienna Contents Preface ............................................................................... 1 Behavioural Ecology ................................................................ 3 Seasonal shift in the diet of the European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus) in Hungarian dry grasslands B. GYŐRI-KOÓSZ, K. KATONA and S. FARAGÓ ..................................... 5 Relations between genetic, geographic and acoustic distances in five populations of speckled ground squirrels Spermophilus suslicus V.A. MATROSOVA, L.E. SAVINETSKAYA, O.N. SHEKAROVA, S.V. PROYAVKA (PIVANOVA), M.Yu. RUSIN, A.V. RASHEVSKA, I.A. VOLODIN, E.V. VOLODINA and A.V. TCHABOVSKY ................................................................ 6 Ontogeny of the alarm call in the European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus): findings from a semi-natural enclosure I. -

RODERICK MAIN Revelations of Chance SUNY Series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology

REVELATIONS OF C HANCE Synchronicity as Spiritual Experience RODERICK MAIN Revelations of Chance SUNY series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology Richard D. Mann, editor Revelations of Chance Synchronicity as Spiritual Experience Roderick Main State University of New York Press Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2007 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 194 Washington Avenue, Suite 305, Albany NY 12210-2384 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Anne M. Valentine Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Main, Roderick. Revelations of chance : synchronicity as spiritual experience / Roderick Main. p. cm. — (SUNY series in transpersonal and humanistic psychology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-7023-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-7024-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Coincidence—Religious aspects. I. Title. II. Series. BL625.93.M35 2007 204'.2—dc22 2006012813 10987654321 In memory of John Mein Main (1930–2006) CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Synchronicity and Spirit 11 3. The Spiritual Dimension of Spontaneous Synchronicities 39 4. Symbol, Myth, and Synchronicity: The Birth of Athena 63 5. Multiple Synchronicities of a Chess Grandmaster 81 6. -

The Inheritance

The Inheritance EDWARD (TED) TODD, 2012 The Inheritance This is Autobiofiction .............................................................................................................. 4 BookEsalen 1. Institute The Father of Human .................................................................................................... Relations, California 1979 ............................................... 17 5 Near the Don River, Russia 1945 ................................................................................... 17 Russians ................................................................................................................................22 The Journey 1957 .................................................................................................................. 35 Uncle Carlos, Argentina 1958 ........................................................................................... 59 Antonio Garibaldi, Buenos Aires, a few months later ............................................. 67 BookOscar 2.1976 The ............................................................................................................................... Son’s Story ........................................................................................... 8270 Budapest 1980 ....................................................................................................................... 88 INTERLUDE:The other Grandma Is Life Really is crazy? a Jewish .................................................................................... -

Century Feminism: a Jungian Exploration of the Feminine Self

20th Century Feminism: A Jungian Exploration of The Feminine Self by Christopher Alan Snellgrove A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama August 4, 2012 Keywords: Carl Jung, Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Archetypes Copyright 2012 by Christopher Alan Snellgrove Approved by Jonathan Bolton, Chair, Associate Professor of English Dan Latimer, Professor Emeritus of English Susana Morris, Assistant Professor of English Abstract The following work uses the theories and methods provided by Carl Jung as a way of analyzing works by three women authors: Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. The primary Jungian notion featured is that of self-actualization—the process by which a person has achieved a sense of wholeness uniting their body and mind to the greater world. Specifically, I examine how the protagonists and antagonists of these texts either complete their Jungian journey towards actualized wholeness. In order to do this, I focus greatly on Jung’s notion of archetypes, and how they either help or hinder the journey that these women are on. A large part of the analysis centers on how actualization might be defined in feminine terms, by women living in a world of patriarchal control. As such, this work continues the endeavors of other Post-Jungians to “rescue” Jung from his own patriarchal leanings, using his otherwise egalitarian theories as a way of critiquing patriarchy and envisioning sexual equality. Jung, then, becomes an interesting bridge between first, second, and third-wave feminism, as well as a bridge between modernism and post-modernism. -

Janus Head 2.4.18

Janus Head Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature, Continental Philosophy, Phenomenological Psychology, and the Arts. Copyright © 2018 by Trivium Publications, Pittsburgh, PA All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Trivium Publications, P.O. Box 8010 Pittsburgh, PA 15216 ISSN: 1524-2269 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 0 Contents Articles The Castle of Debris: Tatsuya Tatsuta’s Formative Abstract Representation of Lacanian Desire George Saitoh 5 Vampires, Viruses, and Verbalisation: Bram Stoker’s Dracula as a genealogical window into fin-de-siècle science Hub Zwart 14 Psychological Perceptiveness in Pushkin’s Poetry and Prose Steven C. Hertler 54 Rousseau’s Languages: Music, Diplomacy, and Botany Fernando Calderón Quindós and M. Teresa Calderón Quindós 80 A Review of the Theoretical Bases of the Beats’ Repudiation of Capitalism Ehsan Emami Neyshaburi “Moral Enigma” in Shakespeare’s Othello? An Exercise in 94 Philosophical Hermeneutics Norman Swazo 128 Into The Void: Nietzsche’s Confrontation With Cosmic Nihilism Clay Lewis 156 Fiction <Nature> Carol Roh Spaulding 190 Poetry At the Locker 208 Total Eclipse 209 Invitation to a Relation 212 Michaela Mullin Notes on Contributors 213 Janus Head 5 The Castle of Debris: Tatsuya Tatsuta’s Formative Abstract Representation of Lacanian Desire George Saitoh “There are only two tragedies in life: not getting what one desires, and getting it.” – Oscar Wilde The Castle of Debris is situated first from the entrance to the large exhibition hall in Tokyo’s National Art Centre. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

African Swine Fever Virus

Biochemical Society Transactions (2020) https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20191108 Review Article Transcriptome view of a killer: African swine fever Downloaded from https://portlandpress.com/biochemsoctrans/article-pdf/doi/10.1042/BST20191108/889177/bst-2019-1108c.pdf by University College & Middlesex School of Medicine user on 10 August 2020 virus Gwenny Cackett, Michal Sýkora and Finn Werner RNAP lab, Institute for Structural and Molecular Biology, Division of Biosciences, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, U.K. Correspondence: Finn Werner ([email protected]) African swine fever virus (ASFV) represents a severe threat to global agriculture with the world’s domestic pig population reduced by a quarter following recent outbreaks in Europe and Asia. Like other nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses, ASFV encodes a transcription apparatus including a eukaryote-like RNA polymerase along with a combination of virus-spe- cific, and host-related transcription factors homologous to the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and TFIIB. Despite its high impact, the molecular basis and temporal regulation of ASFV tran- scription is not well understood. Our lab recently applied deep sequencing approaches to characterise the viral transcriptome and gene expression during early and late ASFV infec- tion. We have characterised the viral promoter elements and termination signatures, by mapping the RNA-50 and RNA-30 termini at single nucleotide resolution. In this review, we discuss the emerging field of ASFV transcripts, transcription, and transcriptomics. Introduction to African swine fever The emergence of African Swine Fever (ASF), caused by ASFV, was first documented almost 100 years ago in Kenya after the disease transferred from warthogs to domestic pigs, which developed a highly lethal haemorrhagic fever; unfortunately ASFV remains endemic in Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. -

Multiproxy Analyses of Lake Allos Reveal Synchronicity and Divergence in Geosystem Dynamics During the Lateglacial/Holocene in T

Multiproxy analyses of Lake Allos reveal synchronicity and divergence in geosystem dynamics during the Lateglacial/Holocene in the Alps Rosine Cartier, Elodie Brisset, Frédéric Guiter, Florence Sylvestre, Tachikawa Kazuyo, Edward J. Anthony, Christine Paillès, Helene Bruneton, Édouard Bard, Cecile Miramont To cite this version: Rosine Cartier, Elodie Brisset, Frédéric Guiter, Florence Sylvestre, Tachikawa Kazuyo, et al.. Mul- tiproxy analyses of Lake Allos reveal synchronicity and divergence in geosystem dynamics during the Lateglacial/Holocene in the Alps. Quaternary Science Reviews, Elsevier, 2018, 186, pp.60-77. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.02.016. hal-01795351 HAL Id: hal-01795351 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01795351 Submitted on 1 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Multiproxy analyses of Lake Allos reveal synchronicity and divergence in geosystem dynamics during the Lateglacial/Holocene in the Alps * ** Rosine Cartier a, b, , 1, Elodie Brisset a, b, , 1,Fred eric Guiter b, Florence Sylvestre a, Kazuyo Tachikawa a, -

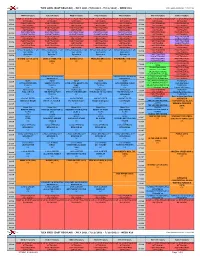

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM MON (7/5/2021) TUE (7/6/2021) WED (7/7/2021) THU (7/8/2021) FRI (7/9/2021) SAT (7/10/2021) SUN (7/11/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR -

Wreaths of Time: Perceiving the Year in Early Modern Germany (1475-1650)

Wreaths of Time: Perceiving the Year in Early Modern Germany (1475-1650) Nicole Marie Lyon October 12, 2015 Previous Degrees: Master of Arts Degree to be conferred: PhD University of Cincinnati Department of History Dr. Sigrun Haude ii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT “Wreaths of Time” broadly explores perceptions of the year’s time in Germany during the long sixteenth century (approx. 1475-1650), an era that experienced unprecedented change with regards to the way the year was measured, reckoned and understood. Many of these changes involved the transformation of older, medieval temporal norms and habits. The Gregorian calendar reforms which began in 1582 were a prime example of the changing practices and attitudes towards the year’s time, yet this event was preceded by numerous other shifts. The gradual turn towards astronomically-based divisions between the four seasons, for example, and the use of 1 January as the civil new year affected depictions and observations of the year throughout the sixteenth century. Relying on a variety of printed cultural historical sources— especially sermons, calendars, almanacs and treatises—“Wreaths of Time” maps out the historical development and legacy of the year as a perceived temporal concept during this period. In doing so, the project bears witness to the entangled nature of human time perception in general, and early modern perceptions of the year specifically. During this period, the year was commonly perceived through three main modes: the year of the civil calendar, the year of the Church, and the year of nature, with its astronomical, agricultural and astrological cycles. As distinct as these modes were, however, they were often discussed in richly corresponding ways by early modern authors. -

ROSALIND NASHASHIBI GRIMM 202 Bowery, New York March 08 – April 18, 2019

ROSALIND NASHASHIBI GRIMM 202 Bowery, New York March 08 – April 18, 2019 GRIMM is pleased to announce a solo presentation by Rosalind Nashashibi (b. 1973 Croyden, UK) at our New York gallery space. This is the artist’s first solo exhibition with the gallery and her fourth solo exhibition in New York. Rosalind Nashashibi is a London-based filmmaker and artist whose practice incorporates painting, printmaking, and photography. Starting in 2014, Nashashibi has expanded her painting practice, creating abstract and figurative works that combine lush colors with sumptuous organic forms. Her Rosalind Nashashibi | Soft Gate | 2019 | Oil on canvas paintings incorporate motifs that are pulled from her everyday environment such as a wine glass or an illuminated taxi sign, which are then reworked in multiple variations. There is both and Helke Bayrle, whom Nashashibi considers her mentors. a softness and an immediacy present in her works that comes The intimacy of this black and white scene is contrasted from an intuitive, process-based exploration of the medium. on the right screen with out-of-focus color footage from Although Nashashibi’s paintings share certain qualities with Nashashibi’s 2005 film, Eyeballing. Throughout Bachelor German Expressionism, they are more reserved, enriched by Machines Part 2, Thomas Bayrle narrates his idiosyncratic their stillness and focus. The simple refinement of the artist’s theory on the materialization of the abstract idea into a paintings can be compared to her films in that they gently thing in the world, in particular the invention of the diesel outline an internal visual language; giving the viewer space engine. -

The Biological Age of a Bloodstain Donor Author(S): Jack Ballantyne, Ph.D

The author(s) shown below used Federal funding provided by the U.S. Department of Justice to prepare the following resource: Document Title: The Biological Age of a Bloodstain Donor Author(s): Jack Ballantyne, Ph.D. Document Number: 251894 Date Received: July 2018 Award Number: 2009-DN-BX-K179 This resource has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource is being made publically available through the Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. National Center for Forensic Science University of Central Florida P.O. Box 162367 · Orlando, FL 32826 Phone: 407.823.4041 Fax: 407.823.4042 Web site: http://www.ncfs.org/ Biological Evidence _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Biological Age of a Bloodstain Donor FINAL REPORT May 27, 2014 Department of Justice, National Institute of justice Award Number: 2009-DN-BX-K179 (1 October 2009 – 31 May 2014) _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Principal Investigator: Jack Ballantyne, PhD Professor Department of Chemistry Associate Director for Research National Center for Forensic Science P.O. Box 162367 Orlando, FL 32816-2366 Phone: (407) 823 4440 Fax: (407) 823 4042 e-mail: [email protected] 1 This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S.