Did the Media Do It? the Influence of News Coverage on the 2006 Congressional Elections1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLBT, Vatican Child Molester Protection --- Newsfollowup.Com

GLBT, Vatican child molester protection --- NewsFollowUp.com NewsFollowUp.com search Obama pictorial index sitemap home Gay / Lesbian News for the 99% ...................................Refresh F5...archive home 50th Anniversary of JFK assassination "Event of a Lifetime" at the Fess Parker Double Tree Inn. JFKSantaBarbara. below Homosexuality is natural, Livescience There's no link between homosexuality and pedophilia ... The Catholic Church would have you believe otherwise. more = go to NFU pages Gay Bashing. Legislation Gay marriage Media Gays in the Military Troy King, Alabama Attorney General, homophobe. related topics: AIDS Health Social Umbrella PROGRESSIVE REFERENCE CONSERVATIVE* Advocate.com stop the slaughter of LGBT's in Iraq GOP hypocrisy? CAW gay and lesbian rights wins, pension info Egale, Canada, to advance equality for Canadian LGBT Gay Blog news Gaydata Gay media database, info Answers Jeff "Gannon, Gaysource Lesbian, gay, Bisexual, Transgender Crist, Foley, Haggard... who knew the GOP was below Community having a coming out party? We could have been DOMA, Defense of Marriage Act Gay World travel, media, news, health, shopping supportive of their decisions to give oral sex to male American Family Association preservation of traditional GLAD Gay Lesbian Advocates and Defenders prostitutes but they went and outlawed it.... family. Boycott Ford for contributing to gay issues. GLAAD Media coverage of openly gay, lesbian, Canada, Netherlands, Belgium and Spain have all bisexual, and transgender candidates and elected legalized gay marriage as of July, 2005 officials in the West does not seem to be focusing on Daily Comet the sexual orientation of those candidates. DayLife "U.S. Republican presidential candidate John Human Rights Campaign lgbt equal rights. -

Accusations of a Tainted Process, Junk Science

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of the ) MB Docket No. 02-277 Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple ) MM Docket No. 01-317 Ownership of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local ) Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 FURTHER REPLY COMMENTS OF TRIBUNE COMPANY ON RESEARCH STUDIES ON MEDIA OWNERSHIP Pursuant to the Commission’s Public Notice, dated July 31, 2007 (DA 07-3470), Tribune Company (“Tribune”) submits these further reply comments on the peer-reviewed research studies that have been submitted in this proceeding. As Tribune and others have demonstrated, the Commission’s Studies 3, 4, and 6 demonstrate (1) that the newspaper rule provides no public interest benefit in terms of viewpoint diversity, because the slant of a newspaper does not correlate with the slant of its cross-owned station, and (2) that the newspaper rule affirmatively harms localism, because cross-owned stations provide more and better coverage of local news and issues than other stations. The results of the Commission’s studies are consistent with one another, and each study has been subjected to a rigorous peer review process that ensures the soundness and the reliability of the results. -

Check Six: the Duke Cunningham Story Ninette Del Rosario Sosa University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Check Six: The Duke Cunningham Story Ninette Del Rosario Sosa University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sosa, Ninette Del Rosario, "Check Six: The Duke Cunningham Story" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2922. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2922 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Check 6: The “Duke” Cunningham Story A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by Ninette Sosa San Diego State University, 2001 Bachelor of Arts in Sociology August 2018 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council _______________________ Larry Foley, MA Thesis Director _________________________ _________________________ Dale Carpenter, MA Rob Wells, PhD Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT This short documentary film is about one man’s ascent, descent and redemption for making an extremely poor personal decision that has impacted his entire adult life. Randall “Duke” Cunningham, 76, is a former U.S. Republican Congressman from California who was sentenced in 2005 to more than eight years in prison for accepting bribes totaling $2.4 million and tax evasion. He was released from an Arizona prison in 2013 and moved to Hot Springs Village, Arkansas because he had a brother and sister-in-law who lived there and they could assist him in getting settled. -

Obama Truthers--He's Gay and His BC Is a Total Forgery

Obama truthers--he's gay and his BC is a total forgery NewsFollowUp.com Franklin Scandal Omaha search pictorial index sitemap home .... OBAMA TOP 10 FRAUD .... The Right and Left Obama Truthers Obama's public personal records The Right and are a total fraud. We agree. It's most importantly a blackmail issue and the public's duty to uncover deception. Left Obama MORE and Donald Trump: Trump's video, $5 million to charities if he releases personal records. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MgOq9pBkY0I&feature=youtu.be&hd=1 Truthers Selective Service card VP Joe Biden Purple Hotel Spencer, Bland & Young Limbaugh, Corsi more 14 Expert Reports on technical analysis of the Obama public records Jerome Corsi believes Obama is Gay. Rush Limbaugh's Straight Entertainment says Obama is gay. HillBuzz interview with Larry Sinclair (gay tryst with Obama) Israel Science & Technology says Obama's birth certificate is a forgery based on expert analysis of the typography and layout of elements in the long-form birth certificate. ... layers Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio (Arizona) determined in 2012 there is probable cause to suspect the document released by the White House as Barack Obama’s birth certificate is a forgery MORE News for the 99% ...................................Refresh F5...archive home NFU MOST ACTIVE PA Go to Alphabetic list 50th Anniversary of JFK assassination Academic Freedom "Event of a Lifetime" at the Fess Conference Parker Double Tree Inn. Obama Death List JFKSantaBarbara. Rothschild Timeline Bush / Clinton Body Count Back to Obama Home Obama Gay Chicago Spencer, Bland and Young Examiner Who is Barack Hussein Obama/Barry Chicago 2012 Campaign Soetoro? It is alleged that Barack Obama has spent $950,000 to $1.7 million with 11 law firms in 12 Lawsuit dismissed below states to block disclosure of his personal records; which includes birth information, K-12 education, Stuart Levine, Ashley Turton below Occidental College, Columbia University, and Clinton, Sinclair Harvard Law School. -

It's Getting Ugly out There

It’s Getting Ugly Out There The Frauds, Bunglers, Liars, and Losers Who Are Hurting America JACK CAFFERTY John Wiley & Sons, Inc. It’s Getting Ugly Out There It’s Getting Ugly Out There The Frauds, Bunglers, Liars, and Losers Who Are Hurting America JACK CAFFERTY John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Copyright © 2007 by Jack Cafferty. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Design and composition by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copy- right Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically dis- claim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis…

5/4/2010 USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis… H-1B Approved Petitioners Fiscal Year 2009 The file below is a list of petitioners who received an approval in fiscal year 2009 (October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2009) of Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker, requesting initial H- 1B status for the beneficiary, regardless of when the petition was filed with USCIS. Please note that approximately 3,000 initial H- 1B petitions are not accounted for on this list due to missing petitioner tax ID numbers. Related Files H-1B Approved Petitioners FY 2009 (1KB CSV) Last updated:01/22/2010 AILA InfoNet Doc. No. 10042060. (Posted 04/20/10) uscis.gov/…/menuitem.5af9bb95919f3… 1/1 5/4/2010 http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resource… NUMBER OF H-1B PETITIONS APPROVED BY USCIS IN FY 2009 FOR INITIAL BENEFICIARIES, EMPLOYER,INITIAL BENEFICIARIES WIPRO LIMITED,"1,964" MICROSOFT CORP,"1,318" INTEL CORP,723 IBM INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED,695 PATNI AMERICAS INC,609 LARSEN & TOUBRO INFOTECH LIMITED,602 ERNST & YOUNG LLP,481 INFOSYS TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED,440 UST GLOBAL INC,344 DELOITTE CONSULTING LLP,328 QUALCOMM INCORPORATED,320 CISCO SYSTEMS INC,308 ACCENTURE TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS,287 KPMG LLP,287 ORACLE USA INC,272 POLARIS SOFTWARE LAB INDIA LTD,254 RITE AID CORPORATION,240 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO,236 DELOITTE & TOUCHE LLP,235 COGNIZANT TECH SOLUTIONS US CORP,233 MPHASIS CORPORATION,229 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LIMITED,219 BLOOMBERG,217 MOTOROLA INC,213 GOOGLE INC,211 BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCH SYSTEM,187 UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND,185 UNIV OF MICHIGAN,183 YAHOO INC,183 -

Capitol Courier U S C a P I T O L P a G E a L U M N I a S S O C I a T I O N

December 2011 Volume 2, Issue 2 the Capitol Courier u s c a p I t o l p a g e a l u m n I a s s o c I a t I o n f e a t u r e Save the House Page Program On August 8, 2011, House Speaker John Boehner and Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi announced they were cancelling the U.S. House of Representatives Inside Page Program. That very same day, former Congressional pages around the This Issue world protested loudly–declaring that it was a historic the decision, keeping the issue in the headlines. Members letter from mistake to end the 200-year-old tradition of young have written letters to their colleagues urging them to the presIDent . 2 people serving in the House of Representatives. support the Program. And two-dozen Members Since the decision, the newly formed Save The of Congress have co-sponsored a bill, H. Res. 397, to boarD of DIrectors . 2 Page Program (STPP) movement has rallied thousands restore the House Page Program. This has forced saVe the of former pages and their supporters to express their Congressional leaders to talk publicly about ways to congressIonal pages . 3 disapproval by writing letters to Members of Congress, keep young people involved in the work of the House. making phone calls, signing petitions, and lobbying But the work is not yet done. What you can Do to Congress in-person on Capitol Hill. Moreover, the STPP, which is currently led by former pages in the help saVe the house movement has helped place op-eds in nearly every Washington, D.C. -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 2006-10-11

THE INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 The Daily Iowan WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2006 WWW.DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ Ousted lab head unveils lab fundraiser BY BRYCE BAUER new hygienic “This is an initiative to find restored by add-ons,” according THE DAILY IOWAN lab and criticiz- enough money to build a better to the website. ing its design, building,” she said on Tuesday. While she was an employee at GILCHRIST’S NEW ORGANIZATION She may no longer work for Gilchrist has On the campaign’s website, the lab, Gilchrist had advocated Details for ‘Iowans Want The Best Lab’ the UI Hygienic Laboratory, but launched the www.iowanswantthebestlab.org, for the “better” model and hold- • An organization created by Mary Gilchrist, former director of the UI ousted director Mary Gilchrist “Iowans Want she outlines her “good, better, Hygienic Lab. ing off on equipment and furni- hasn’t quelled her campaign to The Best Lab” best” designations for the vari- • The organization has set out to raise $2.5 million to fund a larger raise an additional $2.5 million campaign to ous building plans. ture purchases while additional hygienic laboratory, a model the organization terms as “better” than the for the new laboratory. finance The current design is in the money was raised during the current “good” design. two and a half years of A week after she announced improvements Gilchrist “good” category, but “the deci- • The major change the organization would like to see is the reintroduction that the UI fired her for being to the state’s sion to settle for ‘Good’ will be construction. -

AWNMAG5.05 Cover

Table of Contents AUGUST 2000 VOL.5 NO.5 5 Editor’s Notebook Go Web Young (Wo)Man, Go Web 7 Letters: [email protected] InternetCOMIC BOOKS Animation 8 Your Move… Jacquie Kubin looks at how and why packaged gaming companies are adding on-line elements to their business plans. 12 Alter-Net-ive Worlds How would the world of animation be different if instead of being a new tool the Web was an old one? Get ready for some pretty wild “classics.” Martin “Dr. Toon” Goodman takes us theorizing… 16 The Aesthetics of Internet Animation Think Web tools are restrictive creatively? Think again! Chris Lanier, creator of Wildbrain’s Romanov, explains why, in the vein of comics, they are actually a source of freedom. 2000 20 Is There Life Beyond Flash? Flash is the leading tool for Internet animation, but there are a few other options for production and augmentation. Here industry leaders reveal their secrets from high tech 3D software to good, old-fashioned talent. 23 Getting Started On-Line So you want to get into this Internet game? Two of AtomStudios’ animators, Kwesi Ako Kennedy and James Dalby, not only tell you how, but offer tips for success. ComputerADULT ANIMATION Animation 25 Vancouver’s Mainframe Entertainment Since their first 3D CGI television show, the groundbreaking Reboot, Mainframe Entertainment has been producing quality children’s television. Don Perro goes for a tour and finds they are working on more than television now. 29 Writing for CGI:A Talk With Ian Boothby UGUST Ian Boothby, co-writer of Casper’s Haunted Christmas, gives us some insight on the pitfalls and joys of writing for CGI. -

Government Ethics Strategy: Case Study of Foley Scandal

Government Ethics Strategy: Case Study of Foley Scandal Daryl D. Green Department of Energy Lisa Robinson Davis Vital Pathways Leadership Group This investigation explores the American political environment and how amoral behavior associated with the “seven deadly sins” impacts contemporary organizational culture. This case analysis also evaluates Congressman Mark Foley’s scandal related to inappropriate emails to congressional pages. The study is significant due to the fact that public strategy can fail in the aftermath of government-wide unethical behavior by senior officials; this results in a negative perception by taxpayers. Researchers and practitioners therefore are interested in understanding how to improve ethical conduct and regain public trust. This paper is an original study and further contributes to understanding how strategy is influenced by ethical conduct and organizational culture in the public sector. Exploration of Government Ethics Strategy mericans are increasingly worried and cynical of contemporary leadership. Traditional institutions are losing favor, leaving citizens unable to trust their neighbors, churches, Aand government. Additionally, America has a history of unethical behavior by leaders. Political parties market family values and personal integrity like they are selling used automobiles. However, no political party has been found to be absolutely clean. In the quest for power and their own personal ambition, some government officials have been drawn to deadly vices that have led to their personal self-destruction. Tomlin (2007) noted this natural selfish behavior has destroyed families, friendships, happiness, and peace of mind. These moral breakdowns can seep into other factions of the political landscape. For example, in 1998, the media reported the Journal of Virtues & Leadership, Vol. -

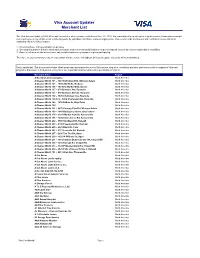

Visa Account Updater Merchant List

Visa Account Updater Merchant List The Visa Account Updater (VAU) Merchant List includes all merchants enrolled as of June 30, 2020. It is consolidated in an attempt to relay the most relevant and meaningful merchant name as merchants enroll at differing levels: by subsidiary, franchise, or parent organization. Visa recommends that issuers and merchants not use this list in marketing efforts for VAU because: 1. We do not have 100% penetration on all sides. 2. We cannot guarantee that the information exchange between the financial institution and merchant will occur in time for the cardholder’s next billing. 3. Some merchants on this list may have only certain divisions or geographic regions participating. Therefore, we do not want to create an expectation that the service will address all account update issues for all merchants listed. Visa Confidential: This document contains Visa's proprietary information for use by Visa issuers, acquirers, merchants and their processors solely in support of Visa card programs. Disclosure to third parties or any other use is prohibited without prior written permission of Visa Inc. Merchant Name Region A Buckley Landscaping Inc. North America A Cleaner World 106 – 3481 Robinhood Rd, Winston-Salem North America A Cleaner World 107 – 1009 2Nd St Ne, Hickory North America A Cleaner World 108 – 130 New Market Blvd, Boone North America A Cleaner World 127 – 679 Brandon Ave, Roanoke North America A Cleaner World 127 – 679 Brandon Avenue, Roanoke North America A Cleaner World 128 – 3806 Challenger Ave, Roanoke -

Strong Disapproval 48 Percent, Matching the High

ABC NEWS/WASHINGTON POST POLL: ‘06 POLITICS – 10/8/06 EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 5 p.m. Monday, Oct. 9, 2006 A Deep Deficit for the Republicans Reflects a Beleaguered President An unpopular war led by a beleaguered president has pushed the Republican Party back to a deep deficit in voter preferences. The Mark Foley scandal, while it hasn’t helped, is a far distant concern, with broad doubts the Democrats would’ve handled it any better. The scandal’s likeliest impact is collateral – forcing the Republicans off the anti-terrorism message that remains their best pushback to broad discontent with the war in Iraq. The result has been to erase the minor gains they’d shown around the 9/11 anniversary. Among registered voters, the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll finds the Democrats with a 54-41 percent lead in the congressional horse race, a gauge of the national mood rather than the status of individual state- and district-level races. (It’s the same, 54-41 percent, among likely voters.) That’s the biggest Democratic lead this close to Election Day in polls back more than 20 years. 70% 2006 Vote Preference (Among registered voters) 65% ABC News/Washington Post poll 60% 55% 55% 54% 54% 52% 52% 52% 50% 50% Dem candidate 45% Rep candidate 42% 41% 40% 40% 40% 39% 39% 38% 35% 30% 25% 20% 1/26/06 4/9/06 5/15/06 6/25/06 8/6/06 9/7/06 10/8/06 Just 32 percent of Americans, moreover, approve of the way Congress is doing its job – the fewest in a decade, although still much better than it was before the 1994 election, in which the Republicans gained control of the House and Senate alike.